The Air Force has quietly hired not one, but seven different companies to provide “red air” adversary support to help U.S. military combat jet pilots train at various bases across the United States. This massive multi-billion dollar contract is the culmination of a major effort within the service that has been years in the making to increasingly rely on contractors to provide these services in order to improve flexibility for training requirements and to save money.

Air Combat Command awarded the subcontracts to Air USA Inc., Airborne Tactical Advantage Company (ATAC) LLC., Blue Air Training, Coastal Defense, Draken International, Tactical Air Support (TacAir), and Top Aces Corporation as part of a single, larger deal on Oct. 18, 2019. The Pentagon’s official announcement notice did not say how much each company stands to make under their respective deals, which will cover work through 2024, though it is possible that there may be performance-based incentives for additional work as time goes on. The Air Force has capped the over-arching contract at no more than $6.4 billion, less than the $7.5 billion it had originally estimated it would cost.

“Contractors will provide complete contracted air support services for realistic and challenging advanced adversary air threats and close air support threats,” the Pentagon’s contracting notice explained. It also said that the Air Force had received a total of eight bids, but did not name the one company that did not subsequently receive an award.

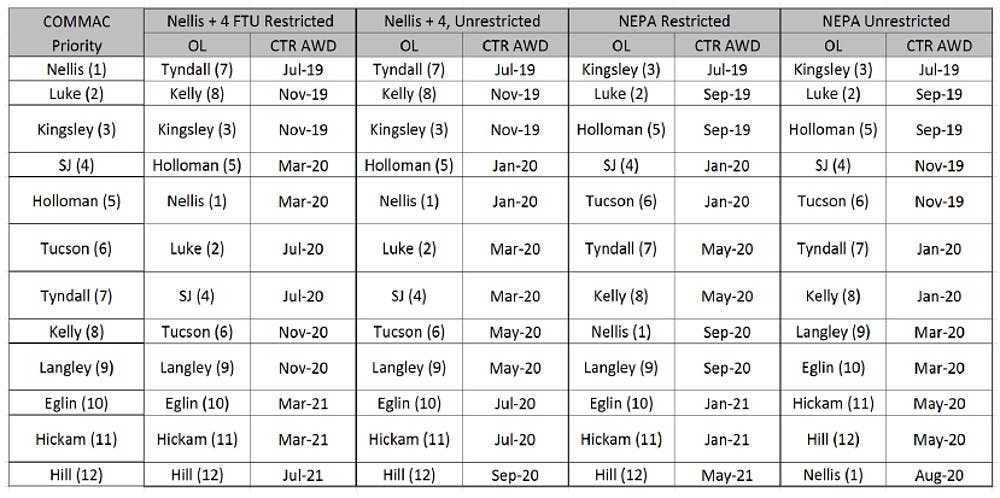

“Work will be performed in multiple locations across the Combat Air Force,” it continued without offering any additional details on the locations. As of June 2018, Air Combat Command was looking at a number of different potential schedules, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone story, all of which would eventually provide aggressor and other training support at a dozen bases throughout the United States, including Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. The Air Force has also said in the past that the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps could potentially piggyback onto the deal as time goes on, but there is no mention that those services has sought to take advantage of this contract already.

As seen in the above table, the original plan envisioned companies getting their first contracts in July 2019, which does not appear to have occured. It’s unclear if this has caused any other schedule delays or if the Air Force had already revised its timetables between June 2018 and the award of these contracts. In hiring seven companies, the service does appear to be trying to make up for any lost time.

ATAC, Draken, TacAir, and Top Aces, the latter of which has its main headquarters in Canada, represent some of the biggest names in the industry worldwide and all have previous experience working with the U.S. military, among others. Since 2017, the first three companies have all been notably expanding their fleets to include new, more capable aircraft that are better able to mimic 4th generation fighter jets specifically in order to better compete for this contract.

ATAC and Draken both bought fleets of upgraded Dassault Mirage F1 fighters from France and Spain, respectively. Draken also acquired a dozen ex-South African Air Force Atlas Cheetahs, a Mirage III derivative. TacAir purchased acquired a number of former Royal Jordanian Air Force F-5E Tiger II jets, upgrading them into what they now call the F-5AT Advanced Tiger configuration.

ATAC already flies Israeli-made F-21 Kfir fighters, another Mirage III-based design, along with less capable Hawker Hunter Mk 58 and L-39 Albatros jets. Draken’s fleet also includes L-39s, as well as L-159E Honeybadgers, along with Cold War-era A-4 Skyhawks and MiG-21bis jets.

Top Aces says on its website that it is in the process of acquiring some number of Lockheed Martin F-16A Viper fighter jets, almost certainly to support this contract. It’s unclear what the source of those aircraft might be, but ATAC had considered buying a number of F-16AMs from Jordan for an earlier aggressor contract with the Navy, but lost that deal to TacAir and its F-5ATs, a decision you can read more about in detail in this past War Zone story. It is possible that those Jordanian Vipers may now find their way to Top Aces, which otherwise operates older Franco-German Alpha Jets and A-4s, though there are other sources of early model F-16s, as well.

Air USA Inc. has a diverse fleet that also includes Alpha Jets and the L-59 version of the Albatros, along with Soviet-era MiG-29UB Fulcrum fighters, and BAE Hawk jets. Coastal Defense’s website shows a number of Albatros variants, including some configured for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions with sensor turrets under the fuselage, as well.

Blue Air Training’s jet fleet consists of Cold War-era BAC Jet Provosts and Strikemasters, the latter of which are more combat-capable derivatives of the former jet trainers. It’s unclear what mix of aircraft from the different contractor fleets the Air Force will actually work with in the end and it is possible, if not probable that lower-density assets, such as Air USA’s MiG-29UBs may not take part in the training missions at all.

Blue Air Training and TacAir also have a number of single-engine turboprops that, along with smaller jets such as the Albatroses and Strikemasters, are ideally suited to training Joint Tactical Air Controllers (JTAC) on the ground to call in airstrikes, which does not have the same performance requirements as simulated air-to-air combat. Blue Air Training also has a number of AH-6 Little Bird light helicopters, but the Air Force does not have any stated requirement for rotary-wing training support.

It is certainly interesting that the Air Force decided to hire so many different companies in the end, but it is not necessarily entirely surprising. As the War Zone

had previously surmised, the wording of earlier contracting documents clearly pointed to a plan to award smaller “task orders” within the main contract to maximize value by bringing on multiple contractors to best meet the requirements for certain aircraft and the ability to conduct flying operations at such a diverse array of locations. The Air Force could easily have had trouble meeting its requirements with a smaller number of contractors, too.

This is also something of a validation for the industry, as a whole, which has been steadily expanding in recent years in line with growing demand, something the War Zone had long predicted and has been following closely. It has been increasingly clear for years that as combat aircraft become more complex and expensive to operate, it will only become less and less cost-effective to use operational types in aggressor and other training roles.

That’s not to say that we won’t see aircraft such stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighters playing the roles of aggressors – the Air Force announced it was doing just that earlier this year – but using alternatives when possible will be ever more essential for keeping costs down and preserving fleet airframe time as time goes on. As the War Zone explained back in 2018:

“The aforementioned commercial adversary support program at Kingsley Field in Oregon is a good poster-child for what contractors can offer. With Kingsley hosting the last F-15C/D schoolhouse in the Air Force, its throughput has suffered in no small part due to an increasing shortage of pilots across the service’s active and reserve components. Draken’s [L-159E Albatros] jets and their pilots will free up instructors from having to play the “red air” role and give them more opportunities to fly with new aviators instead.

…

Even more relevant is that the L-159, which packs a modern multi-mode pulse doppler radar, costs a fraction of what an F-15C costs to operate—between $25k and $45k per hour depending on how it’s calculated—in the adversary role. For new pilots, training flights are often just about learning how to execute intercepts and beyond-visual-range engagements where a very high-performance F-15 isn’t needed to act as the bad guy. As such, flying F-15s versus F-15s for new Eagle Driver pilot training, and for many regular fleet training needs as well, is hugely wasteful. It also depletes precious airframe hours on an increasingly geriatric fleet.”

Beyond “bread and butter” air-to-air training, it’s all about layering these contractor-operated aircraft in with higher-end Air Force assets. The service’s advanced fighters, especially its stealthy F-22 Raptors and the F-35s, simply have an insatiable need for targets during higher-end training to present a real challenge. This can be satisfied efficiently by mixing dissimilar and lower-performing types of aircraft into a larger adversary air plan.

It’s not clear when any contracted companies will actually begin flying sorties under this contract but it’s safe to say that we will increasingly see a diverse group of contractor-operated aircraft supporting Air Combat Command exercises and day-to-day training. Regardless, this is is the long-awaited moment in the history of contractor aggressor services and it will be a game-changer that will allow the industry to only grow and expand more rapidly in the future.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com