Decades-old questions about the potential existence of fantastical anti-gravity propulsion technologies have resurfaced following the Navy’s own disclosure of encounters with unidentified aerial phenomena and our own original reporting on a series of bizarre patents assigned to the U.S. Navy that seem to defy our current understanding of physics and aerospace propulsion. While the discussion continues over whether any such technologies are feasible, the truth is that the theoretical concepts behind them are anything but new. In fact, the U.S. military and the federal government have been formally researching these radical concepts since the 1950s, and according to our own research, those efforts have continued on to this very day.

In our dive into what seems like something of a bottomless rabbit hole of government studies into this exotic scientific realm, we have collected a body of research, news reports, and firsthand accounts. These establish the fact that the types of “anti-gravity”, propellantless propulsion, and mass reduction technologies described in the Navy’s recent “UFO” patents are at least based on more than 60 years of peer-reviewed research conducted and published by the likes of the American Institute of Physics, NASA, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and the Air Force Research Laboratory.

While we can’t say that any of this research led to actually being able to harness “anti-gravity” or extremely advanced next-generation propulsion technologies to any useful extent, the most advanced laboratories under control of both the armed forces and the academic world have certainly been trying their best to get there for the better part of a century. Also, keep in mind that all of this information comes from unclassified sources, and there is definitely more of it than just what is represented here. We can only wonder how much work has been done in the classified realm on what was once openly considered the next massive revolution in aerospace technology.

The Martin Company’s Early Foray Into Anti-Gravity

In terms of the Air Force’s early anti-gravity research, one intriguing first-hand account comes from Dr. Louis Witten, who was a professor of physics at the University of Cincinnati from 1968 to 1991. Throughout his career, Witten conducted research into gravitation, quantum gravity, and general relativity. The last one of these is the theory first put forward by Albert Einstein that proposes that gravity is essentially a warp or curve in the geometry of space-time caused by mass.

During a roundtable discussion titled “Recollections of the Relativistic Astrophysics Revolution” held at the 27th Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics in 2013, Witten recounted his own work on what he somewhat puzzlingly refers to as “the discovery of anti-gravity.”

In his portion of the roundtable, Witten recalls being recruited by George S. Trimble, then serving as Vice President for Aviation and Advanced Propulsion Systems at the Glenn L. Martin Company, which evolved first into Martin-Marietta and eventually merged with Lockheed in 1995 to form Lockheed Martin. The project for which Witten was recruited would come to be known as the Research Institute for Advanced Studies (RIAS) and was officially founded in 1955 by George Bunker, president of Martin, with the goal of advancing aerospace science and development.

“The vice president [Trimble] had the wonderful idea which was to develop anti-gravity,” Witten says, noting he immediately balked at the proposal. “When he tried the idea in public, you can imagine the greeting he received from scientists. So he said to himself ‘those poor bastards, I’ll show them.'” Despite his skepticism, Witten ended up accepting Trimble’s offer to join the powerful Martin executive’s pet project.

Throughout his short speech given at the roundtable, Witten says that even though he faced ridicule within the scientific community for his research, there was no shortage of people who would tell him they knew how to achieve anti-gravity:

“Some of them were very simple ideas. The simple ideas are always hard to combat. Suppose somebody comes to you and says ‘I have a rock of bismuth that demonstrates anti-gravity.’ What do you do?

There was a Vice President of the Martin Company who brought that up, he said ‘I read about a guy in Indiana who says a rock of bismuth…’ I said ‘It’s nonsense.’ He said ‘How do you know it’s nonsense? How do you know there’s no isotope of bismuth that shows anti-gravity?’ What do you say to that?”

Witten’s speech begins around the 1:49:10 mark:

Witten’s ends his speech by pointing out that despite the constant barrage of nonsense claims to investigate, “the power of a Vice President of a big company is so great that the reason there was a laboratory at Wright Field [today known Areas A and C of Wright Patterson Air Force Base] was to find out what we were doing and to help us do it and I got a contract from Wright Field to do it – to do gravity. Which I did, very happily.”

It’s unknown what, if anything, ever came of Witten’s research or the program’s other related research. While we haven’t found a record of him at Wright Patterson to confirm his account, Witten did in fact publish several theoretical articles concerning general relativity throughout that period including “Invariants of General Relativity and the Classification of Spaces”, “Geometry of Gravitation and Electromagnetism”, and “Conformal Invariance in Physics”, all of which list Witten as an employee of the Research Institute for Advanced Studies established by Martin.

The anti-gravity work Witten claims to have conducted at RIAS on behalf of Martin is corroborated by a series of three articles written by aviation journalist Ansel Talbert and published in the New York Herald Tribune on November 20, 21, and 22, 1956. Talbert served as the aviation correspondent for the Herald Tribune from 1953 until the paper shut down in 1966, after which he wrote for various aviation magazines and trade publications.

The articles outline several research institutes that were focused on unlocking the secrets of gravity in the 1950s, including several major universities and private laboratories. A key part of much of the research conducted at these facilities involved relatively down-to-earth topics like electromagnetism, rotating masses at high speeds, and various methods of attempting to reduce an aircraft’s mass.

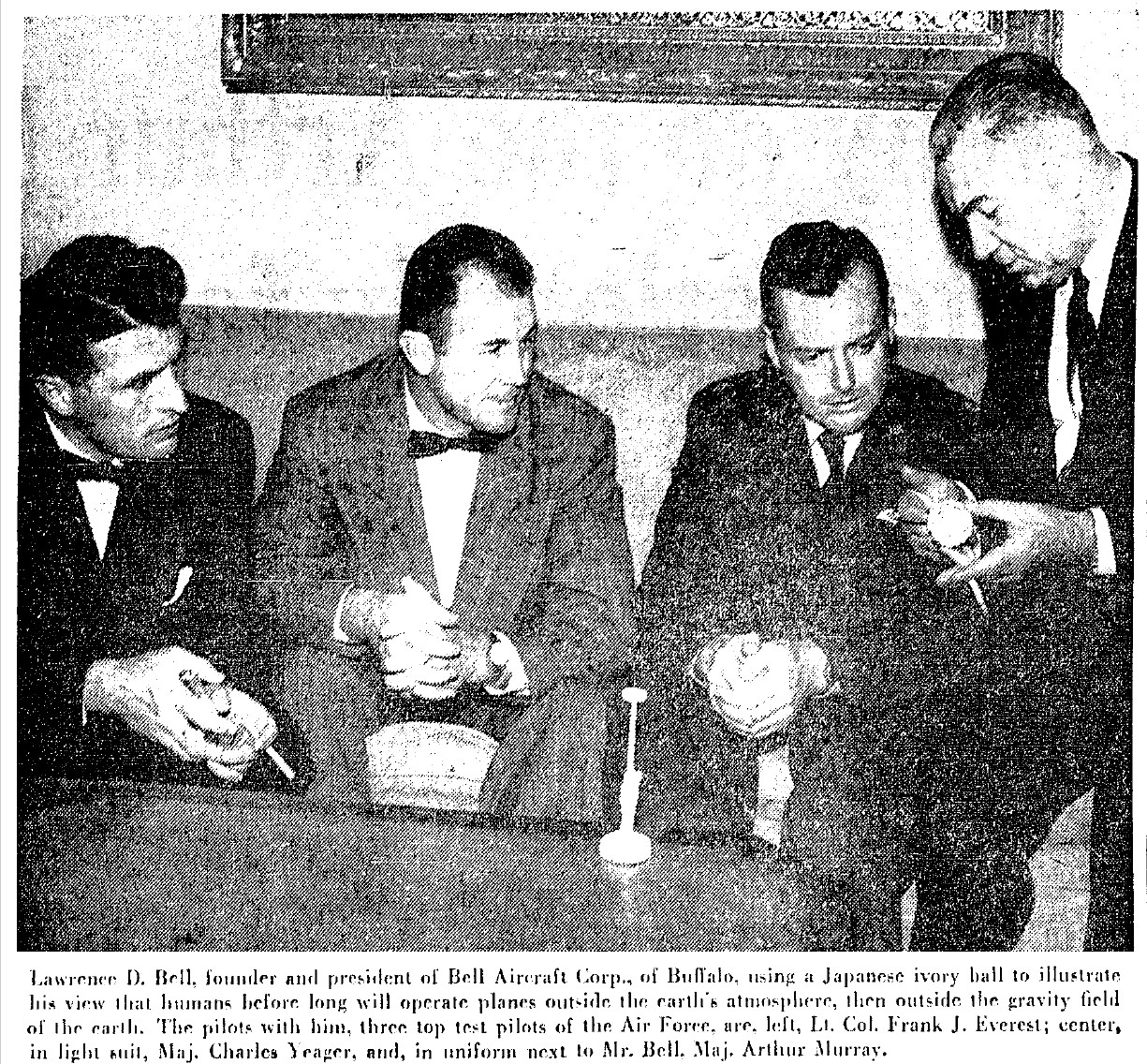

Ansel Talbert was offered a firsthand glimpse into the research conducted at many of the laboratories set up in the 1950s to research gravity and attempts to combat it. His series of articles exploring the subject mention the anti-gravity interests and research of some of the biggest names in aviation: William P. Lear, Lawrence D. Bell, Dr. Igor I. Sikorsky, Martin’s Vice President Trimble, and even frozen foods magnate Clarence Birdseye. “Mr. Birdseye gave the world its first packaged quick-frozen foods and laid the foundation for today’s frozen food industry,” Talbert wrote, “more recently he has become interested in gravitational studies.”

Talbert’s series offers a fascinating glimpse into the many anti-gravity research efforts which were underway in the mid-1950s, but like all accounts of anti-gravity or breakthrough propulsion research, none of the subjects Talbert interviewed offered any suggestion that conclusive working anti-gravity technologies ever came from these endeavors.

Still, Talbert points out that some of the brightest minds in aerospace engineering and physics were devoted to studying gravity at the time, studies which led to important breakthroughs in general relativity:

The current efforts to understand gravity and universal gravitation both at the sub-atomic level and at the level of the universe have the positive backing today of many of America’s outstanding physicists.

These include Dr. Edward Teller of the University of California, who received prime credit for developing the hydrogen bomb; Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton; Dr. Freeman J. Dyson, theoretical physicist at the Institute, and Dr. John A. Wheeler, professor of physics at Princeton University who made important contributions to America’s first nuclear fission project.

It must be stressed that scientists in this group approach the problem only from the standpoint of pure research. They refuse to predict exactly in what directions the search will lead or whether it will be successful beyond broadening human knowledge generally.

One of the biggest takeaways from Talbert’s series is the optimism shared by many of those involved with the project, as well as the stigma surrounding such an endeavor, even back then:

Grover Loening, who was the first graduate in aeronautics in an American university and the first engineer hired by the Wright Brothers, holds similar views. Over a period of forty years, Mr. Loening has had a distinguished career as an aircraft designer and builder and recently was decorated by the United States Air Force for his work as a special scientific consultant. “I firmly believe that before long man will acquire the ability to build an electromagnetic contra-gravity mechanism that works,” he says. “Much the same line of reasoning that enabled scientists to split up atomic structures also will enable them to learn the nature of gravitational attraction and ways to counter it.”

Right now there is considerable difference of opinion among those working to discover the secret of gravity and universal gravitation as to exactly how long the project will take. George S. Trimble, a brilliant young scientist who is head of the new advanced design division of Martin Aircraft in Baltimore and a member of the sub-committee on high-speed aerodynamics of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, believes that it could be done relatively quickly if sufficient resources and momentum were put behind the program.

“I think we could do the job in about the time that it actually required to build the first atom bomb if enough trained scientific brainpower simultaneously began thinking about and working towards a solution,” he said. “Actually, the biggest deterrent to scientific progress is a refusal of some people, including scientists, to believe that things which seem amazing can really happen… I know that if Washington decides that it is vital to our national survival to go where we want and do what we want without having to worry about gravity, we’d find the answer rapidly.”

Transcribed full text versions of Talbert’s articles “Conquest of Gravity Aim of Top Scientists in U.S.,” “Space-Ship Marvel Seen If Gravity is Outwitted,” and “New Air Dream – Planes Flying Outside Gravity” can be found online here, while digital versions of the articles as they appeared in the New York Herald Tribune can be found through the Herald Tribune archives available through the ProQuest database or the New York Public Library system.

The Aerospace Research Laboratories At Wright Patterson Air Force Base

George Trimble, Clarence Birdseye, and Lawrence Bell weren’t the only ones interested in researching anti-gravity. Talbert’s series reported that nearly every major aerospace company at the time was involved in some way with researching “the gravity problem”: Convair, Lear, Sikorsky, Sperry-Rand Corp., General Dynamics, and Avro Canada. Just as Dr. Louis Witten mentioned off-hand in the closing seconds of his speech at the 27th Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics, the United States Air Force also established its own gravity research project at Wright Patterson Air Force Base.

The project was initially known as the General Physics Laboratory of the Aeronautical Research Laboratories (ARL), but its name was changed to Aerospace Research Laboratories at some point. To head the project, the Air Force hired physicist Joshua N. Goldberg who had recently received his PhD from Syracuse University. According to Goldberg’s Curriculum Vitae, he served as a research physicist at Wright Patterson’s Aerospace Research Laboratories from 1956 to 1962, as well as teaching graduate-level classical mechanics at the Ohio State University Extension at Wright Patterson.

Goldberg’s publications from that period show he published a number of theoretical articles in academic journals while working at Wright Patterson, including titles such as “Conservation Laws in General Relativity”, “Measurement of Distance in General Relativity”, and “Einstein Spaces with Four-parameter Holonomy Group.”

Many of Goldberg’s peers at Wright Patterson likewise produced peer-reviewed research in general relativity while at Wright Patterson. Numbers vary, but some accounts say dozens of studies were produced by Goldberg’s group. Some of the reports published from that era include equation-dense publications like “Some Extensions of Liapunov’s Second Method” by J.P. LaSalle and “Gravitational Field of a Spinning Mass as an Example of Algebraically Special Metrics” by Roy Kerr.

Viewpoints differ on the nature of the research conducted at Wright-Patterson under this program. Some have posited that it had to do with actually trying to develop anti-gravity propulsion, while others say its goals were far more mundane.

Nevertheless, the research supported by the Air Force led to what some science historians have called the “Golden Age of Relativity,” a title disputed by others, such as German physicist Hubert Goenner, who argues that “to a great extent what was named the ‘Golden age of relativity’ in the United States, may have been nothing but a feature of a general trend in physics after the ‘Sputnik’-shock.” It’s often claimed that the institute at Wright Patterson and other associated Air Force-funded laboratories were set up merely to investigate reports of Russian anti-gravity research to see if America’s adversaries had achieved what the United States had not been able to.

The anti-gravity research conducted at Wright Patterson concluded in the early 1970s with the passage of the Mansfield Amendments. The first of these, passed in 1970, limited “military funding of research that lacked a direct or apparent relationship to a specific military function.”

According to an Office of Technology Assessment report delivered to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1991, these Mansfield Amendments for some years somewhat slowed the rate of U.S. military research into the types of lofty, abstract topics studied at Wright Patterson throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Following those Amendments, the Department of Defense’s research strategy shifted more towards the proposal-grant model seen at university and private laboratories today.

That is not to say that the U.S. military’s research into gravitation ended with the Mansfield Amendments or was limited solely to Goldberg’s group at Wright Patterson. There is a wealth of research in the public realm that shows the Air Force’s research into these concepts continued long after the scientists at that base moved on to long careers in academia.

In 1972, an ad hoc group with Franklin Mead, then Senior Aerospace Engineer with the Air Force Aerospace Research Laboratories, serving as editor had published a technical report titled “Advanced Propulsion Concepts – Project Outgrowth” for the Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory at Edwards Air Force Base. The document discusses various advanced propulsion concepts ranging from traditional rocket propulsion to “anti-gravity propulsion,” to which an entire chapter is dedicated.

Two main approaches are outlined in Project Outgrowth: those using gravitational absorption, and those based on unified field theory which unites electromagnetism and gravitation. While the document notes that these approaches would “require some major breakthroughs in materials,” it points out that “no new or radical change in fundamental physics” would be required to make these breakthroughs a reality. In other words, Mead and the rest of the study group believed that these types of breakthrough propulsion concepts may be possible once materials sciences caught up with concepts developed in theoretical physics.

Throughout the expansive Project Outgrowth document, Mead and the other scientists also explored field propulsion, defined as those concepts which use “electric and/or magnetic fields to accelerate an ionized working fluid, or react directly with the environment by electric or magnetic effects.” While a range of theoretical field propulsion approaches were analyzed, they concluded that “it would be impossible within the time constraints of this study to evaluate the field propulsion area completely,” noting however that “more radical concepts may be found in the open literature by those interested in pursuing them.”

Still, the document contains quite a few curiosities. One chapter, titled “Electrostatic Effects,” describes the use of electric generators to charge giant metallic spheres buried in the ground six miles apart in symmetrical arrangements. Another sphere would be placed on top of the ground in the center of this arrangement of spheres, which would then be shot up to 620 miles into space when the other spheres are charged with an intense electrical current, according to the document. It is also claimed that vehicles flying in space with charged skins could be used to cause the spheres to change directions instantly without any loss of velocity or use of propellant.

As fascinating as this experiment sounds, there is nothing in the document to suggest the Air Force actually sent metal spheres flying into the sky, and the document points out that “analysis of this concept completely ignores the effect of the immense electric fields of the surrounding environment,” noting that ambient ions accumulating around the spheres would nullify the repulsion effect. “Handling and producing charged objects of the magnitude assumed for the analysis may be well beyond the reach of technology for decades to come“ and “all of the ideas discussed lack theoretical and technical merit,” the study group concluded.

The same document outlines theoretical approaches at using superconductors to achieve electromagnetic spacecraft propulsion, noting that the applications of high energy electromagnetic fields range far beyond propulsion:

The greatest advantage of this concept is that the system is initially charged on earth with a tremendous amount of massless energy which is stored in a low-loss propulsion system. […] Similar to other low-thrust vehicles, this system is capable of accelerating to very high velocities when operating over great distances for substantial periods of time. […] This system could be used to decelerate vehicles approaching the Earth at high speed. Militarily, this concept could, with its high magnetic field, destroy, deflect, or severely damage incoming high-speed projectiles.

The Project Outgrowth document concludes by arguing that while many of these concepts are still out of the grasp of the USAF, advances in materials and engineering could make what in 1972 seemed like fantasy a reality in the decades to come:

Obviously, advancements in certain areas of technology could make a number of concepts suddenly very attractive. Improvements in high energy lasers by several orders of magnitude of energy output or new concepts involving long-distance energy transfer would make both laser propulsion and infinite Isp ramjet very attractive. The development of higher current density superconductors, metallic hydrogen, or even room temperature superconductors would make many of the magnetic concepts more attractive. […]

Radical departures from time-honored, well-proved approaches are either discarded or lack visualization. Possibly, not until man truly becomes a creature of space will the restrictions imposed on his imagination be removed and radically new propulsion concepts devised. We are just beginning to understand the true nature of space and to attempt to utilize this environment for our propulsion needs.

The same concepts explored in the Project Outgrowth document were later examined by subsequent Air Force-funded studies. In 1988, the New York-based Veritay Technology, Inc. submitted the document “21st Century Propulsion Concept” to the Air Force Astronautics Laboratory (AFAL) at Edwards Air Force Base. The document looks at the Biefield-Brown effect, a controversial theory that claims that electrical fields can produce propulsive forces sometimes referred to as ionic wind. The AFAL was able to generate minuscule measures of propulsion with the concept, but concluded that “ion propulsion effects are negligible.”

A similar report from 1989 titled “Electric Propulsion Study” also complied for the Astronautics Laboratory at Edwards outlines a variety of theories and experiments that explore the interactions between gravitational, electrical, and electromagnetic fields. Concepts like ionic wind, the Mach effect, and various applications of high energy electromagnetic fields are discussed.

One brief chapter explores the concept of inertial mass variation using a rotating cylinder filled with mercury. The Air Force concluded that the experiment showed little promise and that “no AFAL action is suggested at this time” but that “should an experiment by external agencies be done with positive results, then this area should be reconsidered.”

Ultimately, the document concludes that while much of the research it cites is still in its infancy, inertial mass reduction techniques may offer the most promising results with further study:

It is recommended that policies and plans take into consideration long time studies in the area of gravity and inertia. These areas deserve more emphasis. This is likely to be more important than any single experimental program. Since chemical propulsion is reaching its theoretical limits and nuclear propulsion has political difficulties, it is more likely that gravitational and electromagnetic studies will lead to future breakthroughs than any nuclear force studies (with the possible exception of more recent low temperature fusion work).

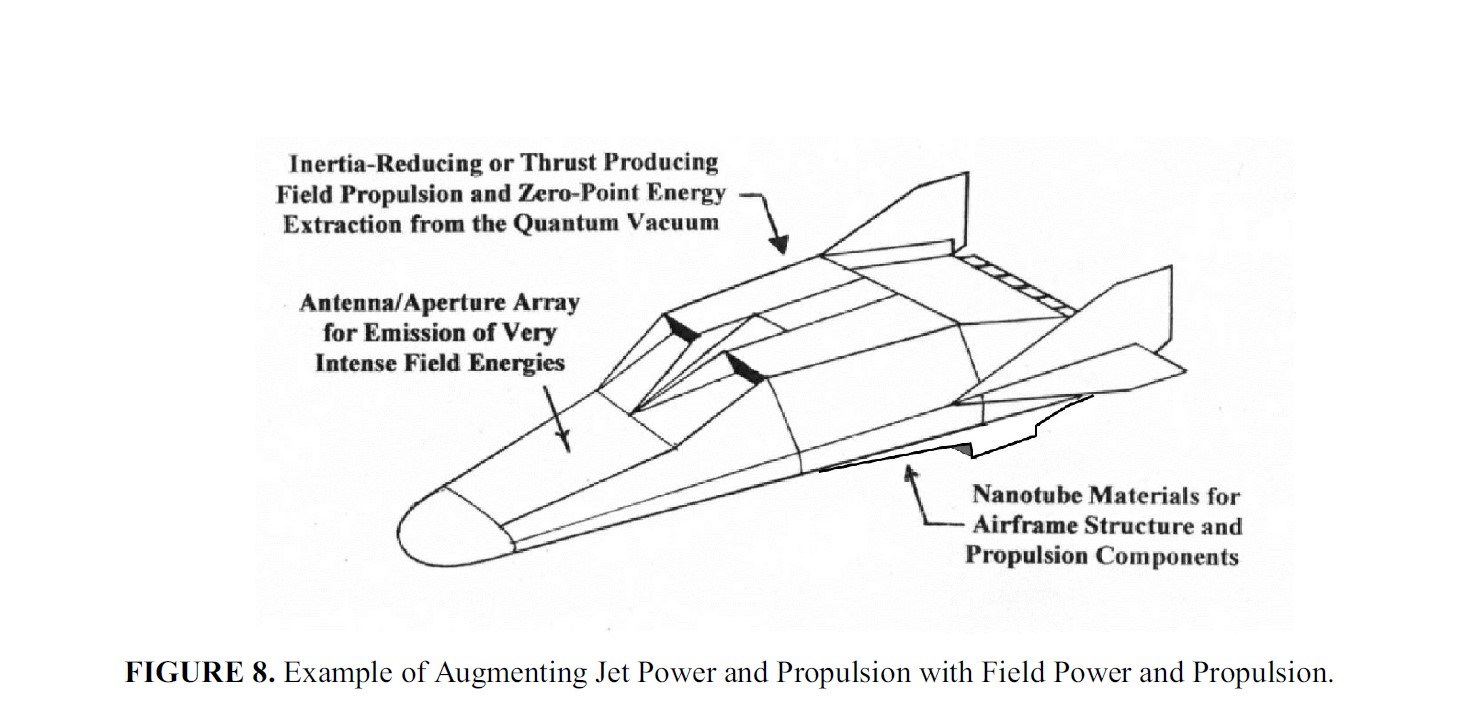

The Air Force continues to look into ways of defying gravity without the use of propellants and some technical reports maintain that this will soon be possible. According to the 2006 study “Advanced Technology and Breakthrough Physics for 2025 and 2050 Military Aerospace Vehicles” which was published by the American Institute of Physics, some scientists claim that next-generation propulsion may be achieved sometime within the next three decades.

The study was compiled at the request of the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and examines the technological breakthroughs that researchers believed could be developed and implemented by 2025 and 2050.

While most of the report centers around compact fusion reactors and the developments of new high temperature composite materials, the section on the “2050 Vehicle” predicts that the jet propulsion and power systems of this hypothetical aircraft will come in the form of propellant-less field propulsion based on the principle of inducing mass fluctuations using high-frequency electromagnetic fields:

One example of propellant-less field propulsion […] proposes the use of high voltage and high frequency electromagnetic (em) field pulsations to induce mass fluctuations within the electronic and ionic structure of dielectric materials – to cause a favorable “gravinertial” field coupling with nearby and distant matter that results in unidirectional force.

Of course, as we now know, the USAF isn’t the sole branch of the military openly looking into next-generation hypothetical vehicles based on concepts of electromagnetic fields and inertial mass variation. Based on the recent announcement declaring a partnership with TTSA, we know even the U.S. Army is also exploring similar concepts for next-generation ground vehicles that exploit the same principles the USAF has explored for decades: mass manipulation, electromagnetic metamaterial waveguides, and quantum physics.

Civilian Research Into Gravitation, Electromagnetism, And Propulsion

The military isn’t the only sector that has for decades conducted research that has explored the boundaries of aerospace propulsion and general relativity. In 1996, NASA funded an endeavor known as the Breakthrough Propulsion Physics (BPP) Program which invited some of the brightest minds in physics and aerospace engineering to propose radical new ideas to propel spaceflight into a new paradigm.

In a paper outlining the BPP program presented at the Second Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions in 1998, its director, Marc Miller, offered an overview of NASA’s aims for the project, noting that “it is known from observed phenomena and from the established physics of General Relativity that gravity, electromagnetism, and spacetime are inter-related phenomena” and that “these ideas have led to questioning if gravitational or inertial forces can be created or modified using electromagnetism.”

Many of the ideas Miller and the NASA BPP program describes were developed or are better understood thanks to the research funded by Wright Patterson, including Hermann Bondi’s concept of negative mass (Bondi’s group at Kings College, London received funding from the U.S. Air Force) and Joshua Goldberg’s theory of gravitational radiation.

In an attempt to achieve breakthrough propulsion based on these concepts, NASA’s project identified three major barriers that stood in the way of their main goal of achieving interstellar travel:

(1) MASS: Discover new propulsion methods that eliminate or dramatically reduce the need for propellant. This implies discovering fundamentally new ways to create motion, presumably by manipulating inertia, gravity, or by any other interactions between matter, fields, and spacetime.

(2) SPEED: Discover how to attain the ultimate achievable transit speeds to dramatically reduce travel times. This implies discovering a means to move a vehicle at or near the actual maximum speed limit for motion through space or through the motion of spacetime itself (if possible, this means circumventing the light speed limit).

(3)ENERGY: Discover fundamentally new modes of on board energy generation to power these propulsion devices. This third goal is included since the first two breakthroughs could require breakthroughs in energy generation, and since the physics underlying the propulsion goals is closely linked to energy physics.

In 1997, NASA’s Lewis Research Center, now known as the John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field, held a conference on these breakthrough propulsion concepts, the proceedings of which are worth a read and contain titles such as “Inertial Mass as a Reaction of the Vacuum to Accelerated Motion”, “Force Field Propulsion”, and “The Zero-Point Field and the NASA Challenge to Create the Space Drive”.

From what little we know or think we know about Salvatore Cezar Pais, the elusive inventor of the Navy’s intriguing if not puzzling anti-gravity ‘UFO’ patents that we’ve explored in our previous reporting, he was working on his PhD dissertation at Case Western Reserve University while serving as a NASA Graduate Student Research Fellow at NASA’s John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field at the time of the conference.

There’s no concrete evidence that Pais attended the workshop, but according to the document’s foreword, 12 students were in attendance. The table of contents for the conference proceedings lists a total of 449 pages, the last of which is a list of workshop participants. However, the versions available online stop at page 389. We are currently pursuing a Freedom of Information Act request to obtain the missing pages.

Confirming Pais’ presence at the conference would be significant because many of the exact same revolutionary concepts that NASA was exploring in terms of unlocking new forms of propulsion and space travel are the same types of concepts found throughout the patents for his “hybrid aerospace-underwater craft” and “high energy electromagnetic field generator.” Many of the participants at NASA’s workshop are also cited throughout Pais’ patents and publications. Placing Pais at the conference would add to the body of evidence which suggests the technologies in the Navy’s patents may have been in the works for the past 20 years, at least as far as the inventor is concerned. In reality though, as we’ve laid out here, many of the concepts in Pais’ patents are similar to those which were researched at Wright-Patterson and other facilities in the 1950s and are still being explored today.

Aside from NASA, academic and independent laboratories have been researching the same principles and approaches the Air Force and other military laboratories have been looking into for decades. One of the most commonly researched areas is in hypothetically reducing an aircraft’s mass using electromagnetism, preferably to zero, and several Lockheed Martin researchers have been involved with quite a few theoretical studies into altering inertial mass (see Haisch, Rueda, and Puthoff, 1998; Rueda and Haisch, 1998; Haisch and Rueda, 1999; and Woodward, Mahood, and March 2001).

A large body of peer-reviewed research into mass reduction involves using advanced superconducting materials such as yttrium barium copper oxide, or YBCO (see Podkletnov and Nieminen, 1992; Li et al, 1997; and Podkletnov and Modanese, 2001). Some of these studies, many of them more than 20 years old, reported observing mass reductions of up to two percent. Of course, just because scientists report a peer-reviewed result doesn’t mean their data can’t be challenged or have been impacted by spurious factors.

Other attempts to overcome and harness gravity focus on the use of electromagnetic fields. In the 2007 publication “The Connection between Inertial Forces and the Vector Potential”, researchers found a connection between electric and magnetic fields, writing that there is a “possibility to manipulate inertial mass” and potentially “some mechanisms for possible applications to electromagnetic propulsion and the development of advanced space propulsion physics.”

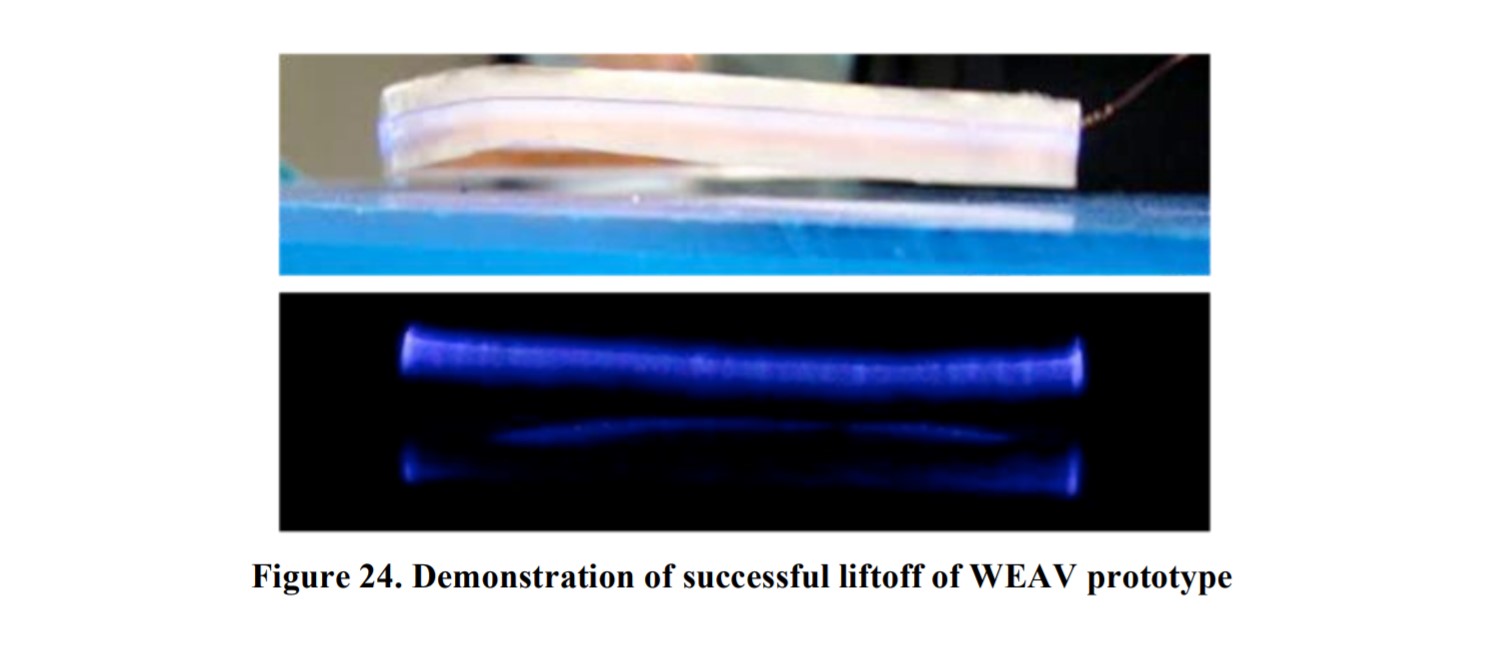

In 2010, an Air Force-funded study at the University of Florida leveraged these principles to design and test a “Wingless Electromagnetic Air Vehicle (WEAV)” which is claimed to employ “no moving parts and assures near-instantaneous response time.” The study writes that this vehicle is designed to support the Air Force Research Laboratory’s strategy to “deliver precision effects: ubiquitous, swarming sensors and shooters” by 2015-2030.

The study was able to produce a disc that “was able to hover a few millimeters above the surface for a sustained duration (about three minutes)” and noted that “prototypes of varying radius were also successfully ‘flown’, demonstrating that WEAV is scalable.”

Many other approaches have focused on the unique properties of novel materials. The 2007 publication “Direct Experimental Evidence of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting” reports “new experimental results suggesting that ‘propellantless’ propulsion without conventional external assistance has been achieved by means of electromagnetic inertia manipulation” using piezoelectric materials, compounds that change shape when subjected to an electrical charge.

In fact, several researchers have reported significant results in mass manipulation using a specific piezoelectric compound, lead zirconate titanate (PZT), which is found throughout several of the Navy’s recent patents. One physicist in particular, Dr. James Woodward of California State Fullerton, has found repeated success in altering the mass of small test samples of PZT.

While the levels of mass reduction Woodward has observed are tiny, so are the samples and energy levels he has used. Still, in one study published with aerospace engineer Paul T. March, then at Lockheed Martin, the authors note that “very large mass fluctuation effects should be producible with only relatively modest power levels,” but are beyond the scope and scale of their study.

Even so, Woodward’s results have been so promising that at least two Air Force studies, the 1989 technical report “Electric Propulsion Study” and the 2017 paper “Movement and Maneuver in Deep Space: A Framework to Leverage Advanced Propulsion”, call attention to his research in particular and note that his approach seems most promising.

However, the 2017 Air Force paper notes that “obvious institutional and funding barriers stand in the way” and that “materials science and engineering work would be required to produce new piezoelectric materials and compensate for natural resonance, mechanical fatigue, and thermal effects.”

Perhaps for that reason and for likely many more, various branches of the Armed Forces have for years been actively researching metamaterials that can propagate high energy electromagnetic fields. Navy budget documents show that between 2011 and 2016, the Navy’s In-House Laboratory Independent Research program conducted research into the “dispersion and control of electromagnetic (EM) waves in the microwave (RF) region, using fabricated metamaterial structures”.

Starting in 2017, the Navy combined several program elements under one title, changing the way individual projects are reported in their budget and thus making it more difficult to know whether this metamaterial research continues today.

Scratching The Surface While Not Knowing What Lies Beneath It

The research cited here is only a brief look at a handful of the numerous studies the Air Force, other branches of the military, and various academic laboratories have conducted into “anti-gravity” and various propellantless propulsion methods, and only those that are available to the public. Anyone familiar with military research and development knows that there is a vast trove of projects, associated data, and technologies the public has yet to be shown and may never be shown.

There have been hints of those secret technologies for years offered by insiders of some of America’s most high-level aerospace research and development outfits. For instance, Ben Rich, the second director of Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, told Popular Science in 1994 the following:

“We have some new things. We are not stagnating. What we are doing is updating ourselves, without advertising. There are some new programs, and there are certain things, some of them 20 or 30 years old, that are still breakthroughs and appropriate to keep quiet about [because] other people don’t have them yet.”

With this in mind, it is possible that there are certain technologies in existence that once were, but may no longer be the things of science fiction.

Regardless, when it comes to harnessing exotic methods of overcoming gravity, the U.S. military’s interest in doing so has continued since the 1950s, and civilian laboratories have been hot on their heels.

We’re still pursuing answers to the enigma surrounding the recent Navy patents, but to say they have come out of the blue and have no scientific basis whatsoever seems to be not entirely accurate based on the decades of research we’ve presented here. The same principles and many of the same names cited in Salvatore Pais’ patents filed for the US Navy between 2015 and 2018 appear throughout numerous NASA studies, the peer-reviewed publications of the scientific community, and the long history of U.S. government-funded research into general relativity and breakthrough propulsion science.

We have to stress once again that this doesn’t mean that actually realizing these concepts and putting them to use is possible at this time, or even ever in the future, for that matter. But it does show that there has been an incredibly long and detailed history of interest by the U.S. military and the scientific community in this exotic field that has resulted in significant amounts of research that spans nearly seven decades. All this occurred in spite of the fact that scientists realized as far back as the 1950s that the topic was largely taboo and often scoffed at by the larger scientific community.

Once again, what exists behind the curtain of the classified realm is the big wildcard here. With so much research present in the unclassified environment, one can only guess as to just how far the military and their industry partners have actually gone in an effort to obtain the ‘Holy Grail’ of aerospace engineering. For some, that speculative answer may be not very far at all. For others, it may be quite the contrary. The fact is we just don’t know. But at least we do know that the topic, in general, isn’t quite as alien as it may seem.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com