Senator Lidnsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican and major political ally of President Donald Trump, has called for an arms embargo and host of other sanctions against Turkey is newly proposed piece of legislation. The draft bill came just hours after Turkish forces, and local partners, launched a new operation into northeastern Syria primarily targeting the U.S.-backed predominantly Kurdish Syrian Defense Forces, or SDF. On Sunday, Trump had given tacit approval to this military intervention, which risks creating all-new conflicts in the region and leading to a humanitarian disaster, as noted in The War Zone

previous in-depth analysis of the situation.

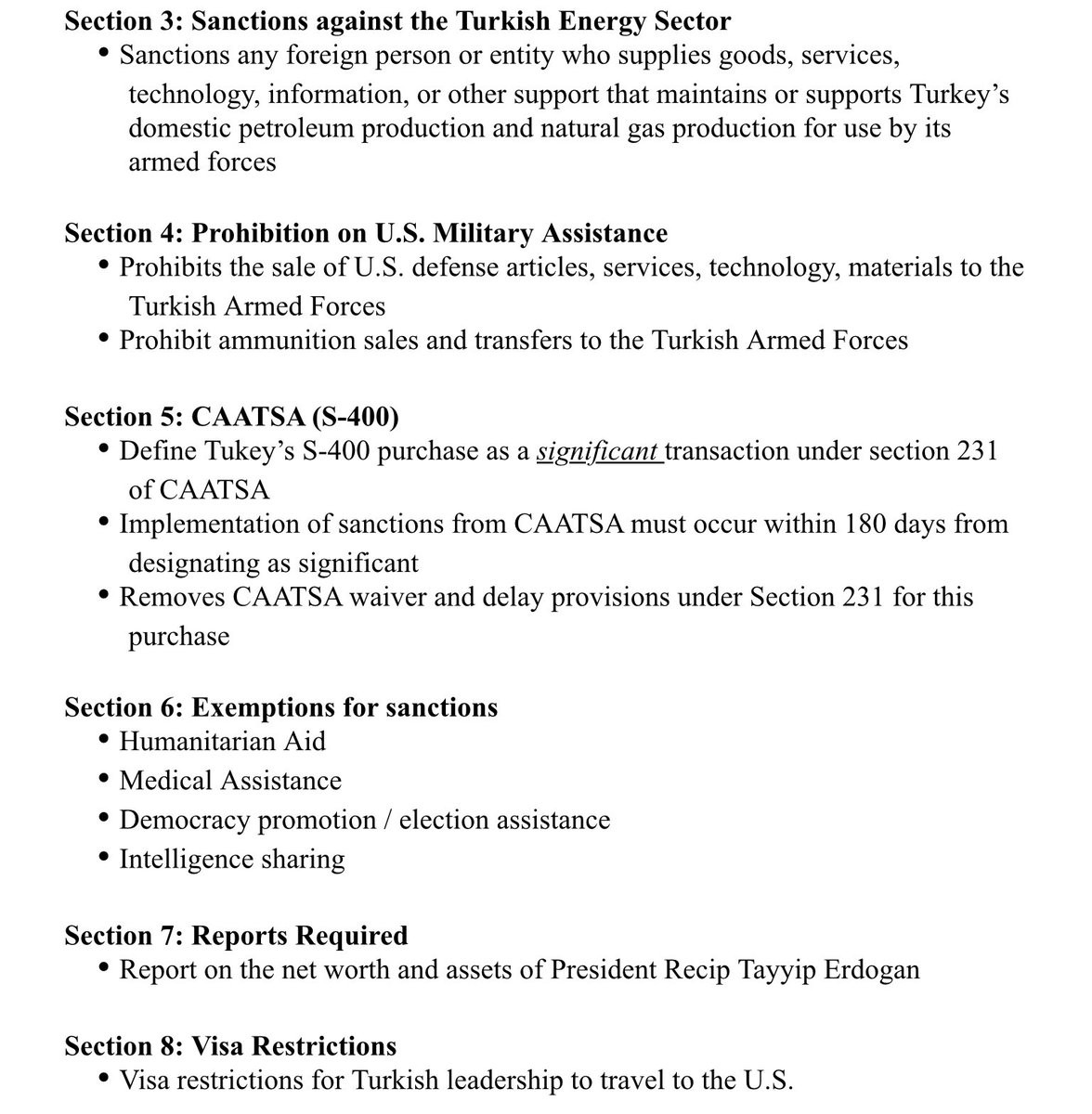

Graham, together with Maryland Senator Chris Van Hollen, a Democrat, drafted what they called the Graham-Van Hollen Turkey Sanctions Bill late on Oct. 9, 2019. Earlier in the day, Turkish combat jets and artillery began attacking various targets in northeastern Syria linked to the SDF as part of what officials in Ankara are calling Operation Peace Spring. Ground forces, including elements of the Turkish Free Syrian Army, or TFSA, subsequently began moving in to seize control of various objectives.

The Turkish government’s ostensible goal is to set up an approximately 20-mile-deep and 75-mile-wide buffer zone on the opposite side of its southern border with Syria. Turkey views the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, also known by the acronym YPG, an organization that provides the bulk of the SDF’s manpower, indistinguishable from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK. Both the United States and Turkey have designated the PKK as a terrorist group, but the U.S. government is of the view that the YPG is a distinct entity. The exact relationship between the two groups is murky and the issue is complex, as the War Zone has explored in detail in the past.

The SDF has been instrumental in rolling back ISIS in northeastern Syria, but has now halted those operations, as have their U.S. and other foreign partners. This could give the terrorist group an opportunity to regroup and there are already indications that sleeper cells in major Syrian cities, such as Raqqa, are now receiving orders to begin launching attacks on the U.S.-backed forces. The fate of thousands of ISIS fighters in SDF custody, as well as their families in various refugee camps, is now uncertain and the U.S. military has reportedly taken custody of a number of particularly high profile detainees.

There are also concerns that the Turkish intervention will result in the ethnic cleansing of Kurds and other ethnic and religious minorities from the border area and spark a humanitarian crisis. Officials in Turkey have said that a “demographic correction” is part of their objectives and say they plan to eventually relocate hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees from Turkish territory into this “safe zone.” The crisis could also provide an opening for Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad and his Iranian and Russian allies to make important territorial gains in the eastern portion of the country.

Senator Graham, who has been a staunch and vocal supporter of Trump’s in recent years, and continues to be one despite a serious and still-growing domestic political scandal, has said that “a disaster is in the making” with the start of the new Turkish operation in Syria and has urged the President to take a harder line opposing the intervention. Trump, for his part, has issued a statement saying he thinks Turkey’s actions are a “bad idea” and has made vague threats to retaliate against the government in Ankara, including to “destroy and obliterate the [Turkish] Economy,” if they proceed in a way that he does not feel is appropriate. Still, he has made clear that he does not intend to more forcefully intervene diplomatically or militarily to block the progress of Turkish or Turkish-backed forces, in general.

The clear objective of the Graham-Van Hollen Turkey Sanctions Bill is to force Trump’s hand or otherwise stymie the Turkish military. Among the most significant of its proposed provisions, which you can read in full below, is a near-total U.S. arms embargo on Turkey.

If it were to become law, the bill “prohibits the sale of U.S. defense articles, services, technology, materials to the Turkish Armed Forces” and “ammunition sales and transfers to the Turkish Armed Forces.” It also levies sanctions on any foreign individuals who sell aircraft, vehicles, and other “weapons or defense articles” to the Turkish military, which, given this blanket language, would include Turkey’s own domestic defense industry. This would end deals many of those companies have with U.S. defense contractors.

These restrictions would “go into effect upon enactment of this Act unless the Administration certifies to Congress – every 90 days – that Turkey is not operating unilaterally (without U.S. support east of the Euphrates and west of the Iraqi border) in Syria and has withdrawn its armed forces, including Turkish supported rebels, from areas it occupied during the operation beginning on October 09, 2019,” the proposed legislation says.

This could have severe impacts on the Turkish military’s ability to operate. A number of its key systems, including its F-16 Viper fighter jets and UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47 Chinook helicopters, rely heavily on cooperation with American or other foreign vendors for spare parts and other support.

Underscoring how significant the embargo might be, in July 2019, there were reports that the Turkish government was hoarding F-16 related spares, among other items, in case the U.S. government imposed heavy sanctions over its purchase of Russia’s S-400 surface-to-air missile system. The S-400 deal, which has now led to Turkey’s ejection from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, is a saga unto itself that you can read about more in these past War Zone stories.

This would not be the first time the United States has imposed such an embargo on Turkey, either. The U.S. government halted arms sales to the country in 1975 in response to the Turkish invasion of northern Cyprus. The year before, Turkey had launched the operation with the ostensible goal of offering protection to ethnic Turks on the island following a coup by Greek Cypriots.

The embargo remained in place until 1978 and had a major impact on the Turkish military’s capabilities. New restrictions on arms sales have the potential to be more significant. The Turkish Air Force, for instance, is one of the largest F-16 Viper operators in the world with around 245 F-16C/Ds in total that a mix of Block 30, 40, and 50 variants. These aircraft have already been active participants in Operation Peace Spring, but could find themselves quickly grounded without a steady supply of spare parts and other support.

Cannibalizing some F-16s to keep other Vipers flying, or locally devised workarounds, as Venezuela has done with its F-16s, could help keep some of the jets in the air, but with increasingly diminished capabilities. The same would go for any other aircraft or vehicles that need spare parts from American vendors, or foreign suppliers who are not interested in getting sanctioned themselves.

The proposed bill also begins the process of putting additional economic sanctions into effect under the existing Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAASTA, over the S-400 sale. This would require the Trump Administration to select five options from a dozen predetermined options, which severe penalties, such as cutting Turkish banks and business off from U.S. financial markets and preventing the Turkish government from securing U.S. loans.

The draft legislation calls for sanctions against Turkey’s energy sectors, including oil- and natural gas-related enterprises, as well as a number of senior Turkish government officials, including President Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself. The bill would create exemptions for humanitarian aid, medical assistance, programs to promote democracy and assist with elections in Turkey, and, interestingly, intelligence sharing with the Turkish government.

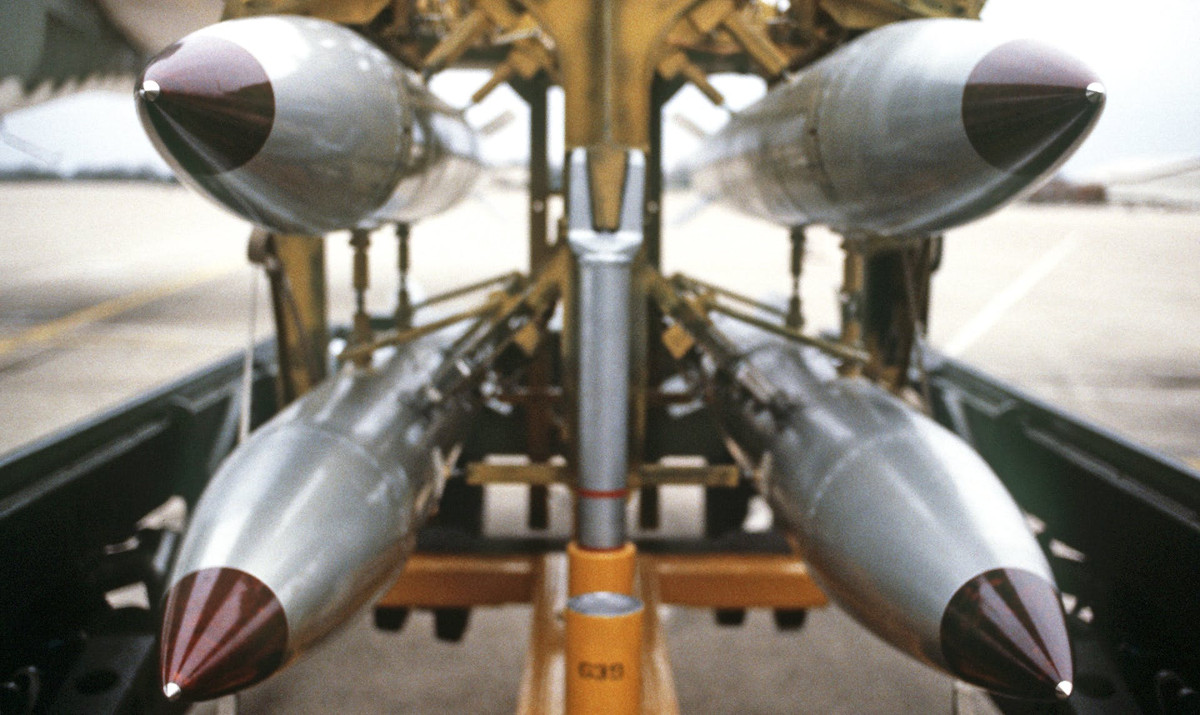

There is also notably no mention of pulling U.S. troops out of Turkey or discontinuing the use of bases in the country. As U.S.-Turkish relations have already soured in recent years there have been increasing calls, in particular, to remove a stockpile of B61 nuclear gravity bombs from the U.S.-operated portion of Incirlik Air Base.

Of course, there is no guarantee that legislators will pass this sanctions package, or, if they do, that Trump, who has a close relationship with Erdogan, will sign it into law. That being said, Kurdish issues do generally enjoy broad bipartisan support in Congress at present and Graham has publicly stated he believes he could secure a veto-proof majority vote.

If the sanctions do come into force, it’s unclear when the Turkish government might begin to actually feel the impacts. It may also further push Erdogan toward other partners, notably Russia, who could supply the Turkish military with new military hardware in spite of any threat of U.S. sanctions. The Russians have already proposed a number of cooperative deals, with regards to both advanced combat aircraft and air defense systems, in light of the S-400 spat.

How the Trump Administration and the Turkish government do or do not respond to this threat in the immediate future remains to be seen, but it is certainly a significant statement of disapproval for the Turkish intervention and Trump’s handling of the situation from one of the U.S. President’s most prominent political allies.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com