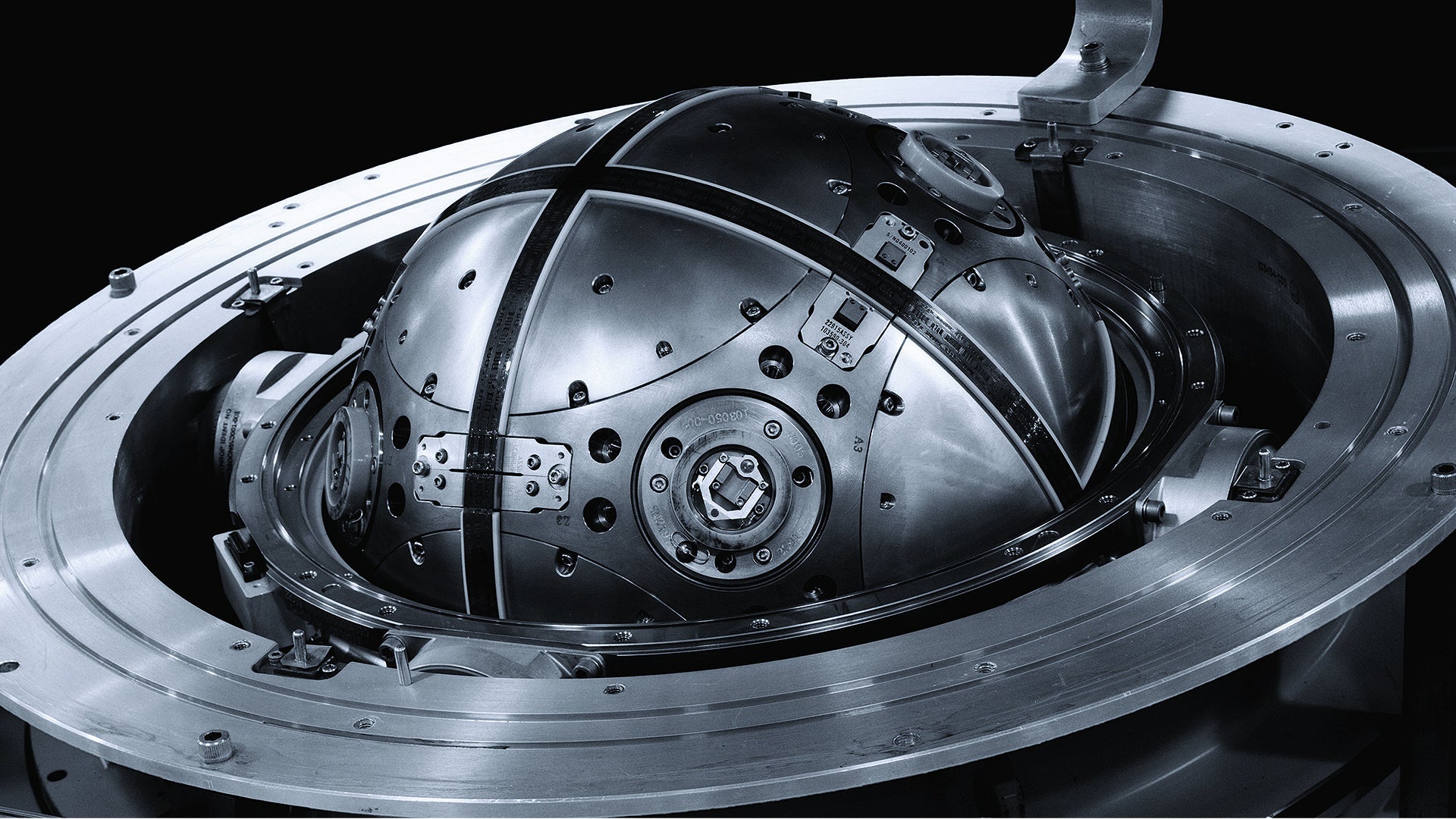

The subject in the striking image above looks like the centerpiece prop in a high-end sci-fi flick, but it is anything but. What you are looking at is the Advanced Inertial Reference Sphere (AIRS) guidance system that was designed to be used as the navigational heart of the highly-accurate LGM-118A Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), also known as the MX (Missile Experimental). Peacekeeper represented the pinnacle of Cold War-era American ICBM technology, but it came at a very high price and with a less than favorable developmental timeline. Even though it dwarfed its Minuteman III stablemate, and it was advanced in many ways, AIRS was by far the most exquisite piece of technology associated with the MX/Peacemaker program. In fact, the system’s existence was a major factor in the Peacekeeper’s reason for being.

The masterful image was taken by photographer and author Martin Miller who had taken up the task of capturing Cold War weaponry in dramatic fashion. The photo seen in its entirety below was featured in Miller’s book Weapons Of Mass Destruction: Specters Of The Nuclear Age.

In the book, Miller describes Peacekeeper’s super INS of sorts as such:

The inertial guidance module used by the Peacekeeper missile, technically called an Advanced Inertial Reference Sphere (AIRS). The AIRS redefined the concept of accuracy possible for ICBMs. Rather than being gimbal-mounted, the sphere floats in a fluorocarbon fluid within an outer shell. The gyroscopes and accelerometers are positioned within the sphere as are the three hydraulic thrust valves and turbopump used to maintain stable orientation of the sphere. The labor to assemble its 19,000 individual parts was enormous.

So yeah, this thing was really something. In fact, some would argue it was among the most incredible pieces of technology that came out of the Cold War. AIRS was critical in lowering the circular error probable (CEP, aka accuracy) of the missile down to 40 meters. The Minuteman III, which remains in service today, has a CEP of roughly six times that. The very idea that an ICBM could be so accurate was a major factor in bringing the Peacekeeper to life in the first place under what was then known as the MX program.

Nuclearweaponsarchive.org has a more detailed description of AIRS:

The AIRS (Advanced Inertial Reference Sphere) is the most accurate inertial navigation (INS) system ever developed, and perhaps marks the end of a long process of continuous refinement of INS technology.

This immensely complex and expensive INS unit has “third generation” accuracy as defined by Dr. Charles Stark Draper, the leading force in the development of hyper-accurate inertial guidance. This translates into INS drift rates of less than 1.5 x 10^-5 degrees per hour of operation. This drift rate is so low that the AIRS contributes on the order of only 1% of the Peacekeeper missile’s inaccuracy, and is thus effectively a perfect guidance system (i.e. a zero drift rate would not measurably improve the Peacekeeper’s performance).

Very little of the precision of this guidance system is even exploited during a ballistic missile flight, it is mostly used simply to maintain guidance system alignment on the ground during missile alert without needing an external reference through precision gyrocompassing. Most ICBMs require an external alignment system to keep the INS in synch with the outside world prior to launch. The AIRS is probably as good as any INS for ICBM guidance needs to get.

The penalty for this extreme level of accuracy is tremendous complexity and cost. The AIRS has 19,000 parts. In 1989 a single accelerometer used in the AIRS (there are three) cost $300,000 and took six months to manufacture.

There are very few applications requiring such precise guidance and independence from external references. In fact, beyond ICBM guidance, none have been identified. If the requirement for complete autonomy is eliminated, extreme guidance accuracy is available at a small fraction of its cost and weight. For example, the advent of satellite positioning systems like GPS (Global Positioning System) and GLONASS, which permit centimeter-level accuracy over unlimited periods of operation with only a light inexpensive receiver. NASA spcecraft require extreme guidance precision, but use external navigation cues to obtain it. Even new nuclear weapon guidance programs have shown a willingness to sacrifice autonomy for cost and weight. The proposed BIOS (Bomb Impact Optimization System), a glide-bomb adaptation of the B-61, has proposed using GPS for guidance instead of an INS. Given the competition from advanced external reference-based approaches, INS technology has probably reached the end of the line as far as accuracy goes.

The last paragraph is right on the money. Today, ring-laser gyro INS systems with embedded GPS come in tiny packages and can sustain massive G forces allowing them to be packed into everything from missiles to artillery shells. You can read all about these fascinating systems in this past piece of mine.

Before GPS was available to correct for drift, it’s amazing the lengths engineers went through to make inertial navigation systems as accurate as possible. Beyond making a near-perfect mechanical gyro-based INS at virtually all costs, other forms of navigation were used to help update less capable INS systems. Maybe the most capable were astronavigation units that found their way onto strategic aircraft like the SR-71 Blackbird and B-2. Even the Trident SLBM uses astronavigation to update its less capable INS. You can read all about these incredible systems here. The idea that Peacekeeper just used AIRS alone to be able to deliver up to a dozen nuclear warheads as far as some 9,000 miles from its launch point is a technological triumph that is far larger than it is given credit for.

Even though the fact that AIRS was even possible helped bring Peacekeeper into existence, it also hurt its chances at wider deployment, among a number of other major factors. Even though it was literally the heart of the missile’s concept, its extreme complexity meant that the “operational” missiles that were deployed starting in 1986 didn’t even have an INS installed. They were useless. It wasn’t till 1988 that the missiles began to be fitted with this critical component.

Just 50 operational LGM-118As were ever deployed. They finally left the inventory entirely in 2005. In all reality, the START II treaty had a huge impact on the missile’s utility. If each missile was to be fitted with only a single warhead, the Minuteman III was a far cheaper way of sustaining America’s somewhat questionable ‘nuclear sponge.’ Also, the idea behind the Peacekeeper was being able to accurately hit Soviet warhead-packed ICBMs in their individual silos, something Minuteman wasn’t precise enough to do. The fact that Peacekeeper was never deployed under a survivable concept as originally envisioned also hurt its career. But Peacekeeper still stands as a technological marvel, with its incredibly complex, but incredibly capable AIRS being its true triumph in technology and made the missile concept worth pursuing at all during the twilight of the Cold War.

Hat tip to @atomicarchive who inadvertently prompted this interesting little journey into the Peacekeer’s past. Also, I want to give a big thanks to Martin Miller for allowing us to share his awesome image. Make sure to check out his website linked here.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com