North Korea appears to have test-fired a submarine-launched ballistic missile, or SLBM, from an offshore platform for the first time in three years, with it crashing down in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ. The launch follows the announcement that the U.S. and North Korean governments had agreed to begin new working-level talks on the latter country’s nuclear weapons programs. It also comes amid growing strains between the United States and its regional allies, Japan and South Korea, over a variety of issues on and off the Korean Peninsula.

South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff said that the North Koreans had fired the missile in the waters off Wonsan on that country’s Eastern Coastline in the early hours of Oct. 2, 2019, local time. The weapon flew just shy of 280 miles, but along a lofted trajectory with an apogee of around 565 miles, landing in the East Sea some 217 miles north of Japan’s Oki Islands. With a flatter trajectory, the missile may have been able to fly more than 1,240 miles, according to Japan’s Kyodo News.

South Korean authorities stressed that while they had assessed that the missile was an SLBM, they believed a submerged test launcher had actually fired the weapon, rather than a submarine. This is an important caveat given that the North Koreans offered the first public look at the conversion of an old Soviet-era design into a ballistic missile sub in July. U.S. officials have reportedly concurred with South Korea’s initial assessments, though both countries were continuing to gather and examine information about the test.

South Korean authorities also said that the missile in question was likely a member of North Korea’s solid-fuel Pukkuksong ballistic missile family. This includes the Pukkuksong-1, the country’s only known SLBM to date, and the land-based Pukkuksong-2, which is based on the submarine-launched weapon. North Korea has not, at the time of writing, released any photographs or video footage from its latest test launch.

It is generally much faster and easier to launch solid-fuel missiles than liquid-fuel ones, which, on land, makes it more difficult for an opponent to spot preparations to launch such a weapon before it occurs. They are also ideally suited to submarine-launched applications, given the difficulties and safety risks generally associated with storing liquid rocket fuel and then pumping it into missiles before firing them.

Based on the information at hand, however, North Korea’s most recent missile test involved a design with a greater range than the Pukkuksong-1, also known as the KN-11. Japanese authorities also initially reported that there had been two missiles, but subsequently revised that statement to suggest that what they had detected was one of the weapon’s stages separating in flight. The ground-launched Pukkuksong-2, also known as the KN-15, is a two-stage derivative of the earlier missile.

In August 2017, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un had toured facilities involved in the production of solid-fuel rocket propellants and lightweight wound filament rocket casings. During one of those visits, he had stood in a room with a poster that made reference to a still unseen Pukkuksong-3. It is possible that this could be a two-stage SLBM design that uses a wound filament rocket motor to reduce weight in order to fly even greater distances, or simply to free up space for more fuel or heavier warheads.

New North Korean SLBM developments make good sense, given that the regime in Pyongyang revealed the existence of their work to convert a Soviet-era Romeo class attack submarine into a ballistic missile sub in July. This diesel-electric submarine would offer limited capabilities and be relatively easy to track, but could still present significant headaches for the country’s opponents, including the United States, which you can read more about in The War Zone‘s past analysis of this development program.

Whatever the exact specifications of the missile might turn out to be, this test is already especially notable for a number of reasons. In addition to being the first time North Korea has launched an SLBM from a sea-based platform since 2016, this is the longest range weapon the regime in Pyongyang has tested since 2017, when it declared a self-imposed moratorium on long-range missile launches and nuclear tests.

That moratorium only extends to intermediate and intercontinental ballistic missiles, with ranges above 1,864 miles, so the North Koreans are not technically breaking their pledge. At the same time, this represents a clear escalation in North Korea’s signaling after a slew of tests involving new guided rockets and short-range ballistic missiles earlier this year.

The exact signal North Korea may be attempting to send now is not entirely clear. On Oct. 1, 2019, the U.S. State Department had announced that there would be new talks between American and North Korean officials within the next week, the first such engagement after months of stalled negotiations in the aftermath of the failed second summit between President Donald Trump and Kim in Vietnam in February. North Korean officials also said they were ready for new talks.

Since then, Kim and other North Korean officials have repeatedly threatened to go down a “new path” if the United States does not meet various demands, including relaxing sanctions. Many observers had taken this to indicate North Korea’s willingness to abandon its missile and nuclear testing moratorium. Trump and his Administration have repeatedly downplayed the earlier, short-range weapon tests that have occurred in recent months.

With the Trump Administration now embroiled in major political scandal, which could have serious domestic ramifications, North Korea may be concerned that its opportunity to deal with Trump himself, who has remained very positive about the prospects of success from future negotiations with Kim and has been inclined to offer concessions in the past, may be running out. As such, North Korea could be attempting to influence the upcoming talks with its SLBM launch, while still, technically, abiding by its stated testing policy.

At the same time, North Korea might be more focused on sending messages to America’s regional allies South Korea and Japan, who are, themselves in the midst of an unprecedented political spat. This led to the collapse of a Japanese-South Korean intelligence sharing agreement in August, which many are concerned will only limit the ability to monitor and assess various North Korean developments, including missile tests. Japan has sought to quell these concerns and plane spotters online noticed that one of the Japan Air Self Defense Force’s RC-2 electronic intelligence aircraft had taken off following the new SLBM test.

Regardless, North Korea “appears to aim to strengthen its negotiating hand to the maximum,” South Korean Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong Doo said on Oct. 2, 2019. “It also appears to take into consideration multiple factors, including our military’s demonstration of its latest military assets yesterday.”

On Oct. 1, 2019, South Korean President Moon Jae In had marked his country’s Armed Forces Day with a ceremony that showcased, among other things, the country’s new F-35 Joint Strike Fighters. The North Korean regime has often singled out these stealthy aircraft as something they see as a particularly significant threat.

“Peace is not something that is defended, but created,” Moon said in his speech. “Our military’s iron-clad security supports dialogue and cooperation, and enabled [the country] to boldly walk toward permanent peace.”

The North Koreans may have interpreted this as a sign that the attitude of the South Korean government, which has, in the past, been working to dramatically improve and potentially even normalize relations with the North, might be shifting. Of course, there have been reports that Moon’s Administration is irate over how U.S. government policies, particularly sanctions, have threatened to scuttle progress in their own negotiations with Pyongyang.

The SLBM test also comes as Japan’s present government continues to push ahead with plans to establish multiple U.S.-supplied Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense sites, despite missteps and growing costs. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has, in general, cultivated a very close relationship with Trump and has largely adopted a policy toward North Korea that mirrors that of the U.S. governments, to the ire of Pyongyang.

“Such a ballistic missile launch is in breach of U.N. Security Council resolutions and we strongly protest and condemn it,” Abe told reporters on Oct. 2, 2019. Japan has also filed a formal complaint about the test.

In September 2019, Japanese media reported, citing unnamed sources, that the country’s Self Defense Forces had failed to track some earlier North Korea short-range tests. The latest North Korean test may, in part, be another attempt to demonstrate their continued ability to target Japan.

If nothing else, North Korea’s new SLBM test underscores how the regime in Pyongyang continues to advance its missile and other military development programs in spite of U.S. and other international sanctions. Kim is also continuing to making it clear that the status quo on the Korean Peninsula could very rapidly change if the regime in Pyongyang does not see the kind of progress in any future negotiations that it wants.

Update 5:35 PM:

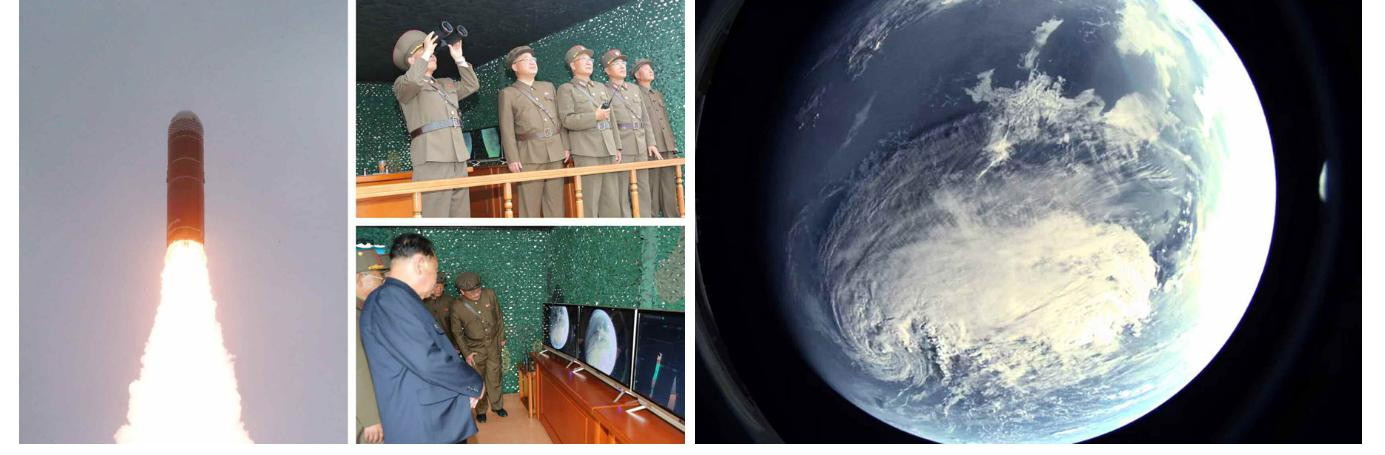

North Korean state media has now officially said that the country has successfully tested the new Pukkuksong-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) and released photographs of the test. The images show that this was indeed an underwater launch, but there is nothing to suggest a submarine was involved. The missile itself looks significantly more advanced than either the Pukkuksong-1 SLBM or the ground-launched Pukkuksong-2.

This is a good rundown of what is particularly notable of what can be seen in the official pictures of the launch:

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com