Earlier today, C4ISRnet.com posted a colorful piece about how the German radar company Hensoldt tracked a pair of F-35s that were departing the Berlin Air Show in 2018 with their “TwInivs” passive radar system. The article was well written and brings up the most glaring points regarding Hensoldt’s claims. Yet my inbox and DMs started filling up with readers showing great concern and amazement regarding what some are saying on social media is the “end of stealth” technology. They wanted to know what to think of all this. Well let’s start with this: no, passive radar doesn’t invalidate the need for stealth and stealth isn’t just about hiding from radar, it is about employing a broad cocktail or measures to drastically increase survivability via limiting the adversary’s ability to detect and target you. And guess, what? It isn’t a magical cloak of invisibility. It never has been and it never will be. And passive radar isn’t a magic stealth detection tool, either.

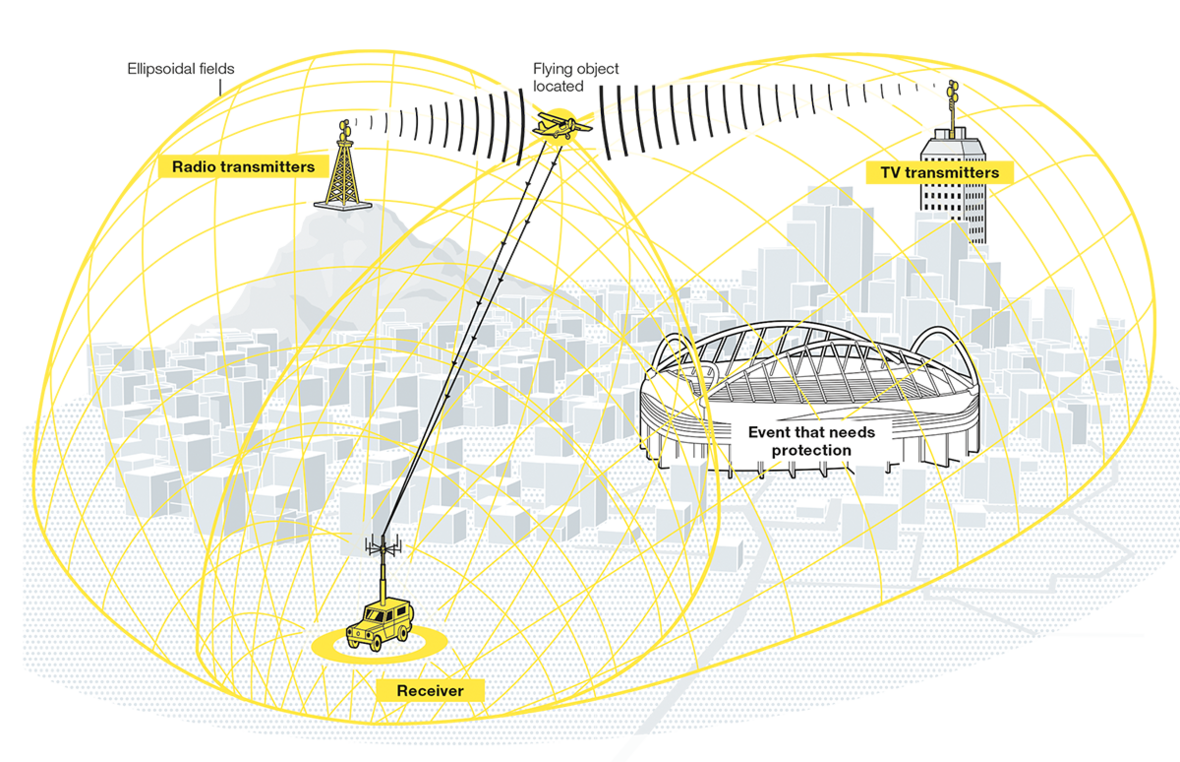

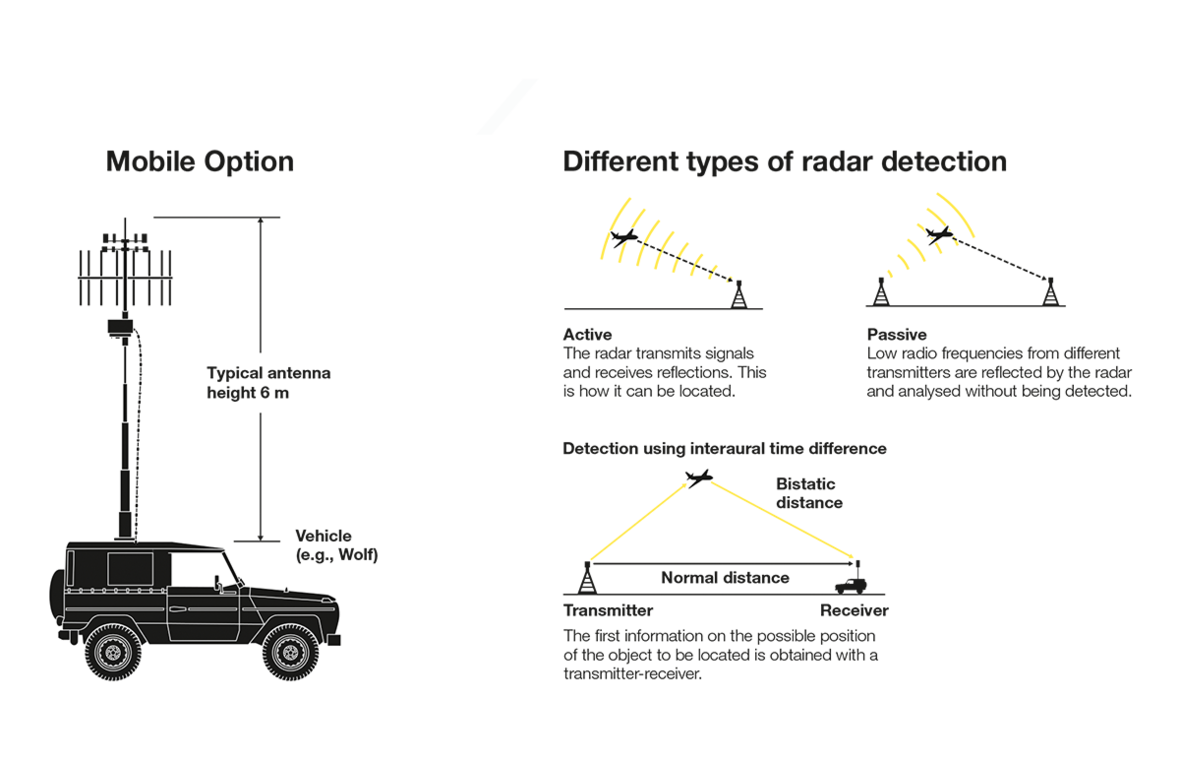

At its most basic, the passive radar concept uses ambient RF radiation, such as emissions from cellphone towers, television and radio broadcasts, and more, instead of its own active radar emitter, and uses returns from those signals to detect targets moving through an area of the sky. The concept has been around for a long time. It dates back to the dawn of radar, with passive radars seeing service during World War II. Multiple weapons manufacturers in multiple countries have been pursuing the technology, to varying degrees, in recent decades.

In fact, it seems that every few years an article makes a big splash by declaring that stealth technology may be invalid due to passive radar system advances. Usually, these articles are packaged with the threat de jour—Iran, Russia, China, etc. Similar claims are now made in articles about low frequency and quantum radar technology today.

Hensoldt’s own claims are over a year old and came at a time when Germany was looking at buying the F-35to replace its Tornado fighters. But really, anything on this type of topic seems to spark a bit of misplaced hysteria, and when the F-35 is the subject of attention along with it, it is bound to grab eyeballs.

As the years have progressed, passive radar has not slashed the utility of stealth technology for a laundry list of reasons. First off, just detecting something unknown in your vicinity does not mean that the target can be accurately classified or engaged. In other words, in most cases, passive radar does not provide engagement quality telemetry for which to employ weapons. It is an awareness tool largely used for cueing other, more traditional sensors.

In other words, it could be used to direct other air defense sensors, such as search and fire control radars, toward an area of the sky that said object appears to be in. This is a worthy capability, as it is possible that some of those sensors will be able to get a better track on the aircraft, especially by varying tactics with the knowledge that they are looking for a low-observable target. But considering that stealth aircraft are optimized to evade detection specifically from the types of radar bands used by these radars, especially from certain aspects, just directing their beams to an area of sky may be a fruitless endeavor. This is especially true if said stealthy target is at a significant distance from those sensors and at a favorable aspect in relation to them. And even if tracking is realized, it would likely be intermittent and not long continuous enough to guide weapons onto the target.

Also, once those sensors are cued by the passive radar system, the aircraft being hunted for will know full well that this is occurring and will employ route changes and advanced electronic warfare capabilities to confuse, spoof, or blind those radar systems. These active sensors give away their location by emitting, so the aircraft or other platforms it is networked to, could also elect to destroy some or all of those threatening sensors if they pose a dire threat to its mission or if the aircraft’s mission itself is to do so. So, once the passive radar does its job and cues other higher-fidelity active sensors onto the target area, those sensors are now at risk of being obliterated.

Where the passive radar has an advantage, even over its active counterparts, is that it doesn’t emit radiation that can give away its location or even the fact that it is present in the region. That means it is very hard to hunt down and destroy. That is until it broadcasts information to other air defense nodes, such as to cue fire control and/or search radars, if it does so without being connected to them via a hard line. In most cases, if the passive radar was hard-wired to the other sensors, it would be in a fixed position or near those systems anyway, thus making it vulnerable to attack, too. The vulnerability of any integrated air defense node talking to another via radio emissions depends on what type of data-link and its associated hardware is being used. Regardless, it is something very important to consider.

Passive radars also rely on dense third-party RF radiation to exploit a medium in which stealthy aircraft can be spotted. So, using it in highly remote areas would be problematic if not totally useless. In other words, because the radiation level cannot be controlled by its operators, the system is subject to the ambient RF environment it is placed in. This limits how and where the system can be effectively employed. Even then, their range and fidelity are limited.

For instance, in the German passive radar story, the company says it tracked two F-35s flying, but at the time those F-35s had their transponders on and were talking on air traffic control frequencies (emitting their own RF energy). They may have even had their radars on utilizing basic modes. They were also flying with their radar reflectors attached to their fuselages and with their aircraft in a non-combat configuration and software mode. The operators also knew the local RF environment very well and how to optimize the system to spot aircraft that they already knew were going to be there. Even under these near ideal conditions, they claimed they tracked the aircraft for about 90 miles. That is a substantial distance, but is no way indicative of what ranges would be possible under actual combat conditions, and that’s even if they would see an unannounced, emissions silent, combat configured, electronic warfare-enabled F-35 at all.

Where passive radar systems may be most capable is when they are paired with an advanced infrared search and track system. This could allow for more precise secondary targeting of whatever the passive radar sees on its scope. It could also provide classification data and even weapons employment information. But IRSTs, especially those mounted on the ground, have major limitations themselves, especially in terms of range and fidelity, which can be highly environmental conditions-dependent, not to mention scanning speed.

The ability to help direct fighters onto potential targets of interest that normal radars don’t see is another potentially potent application for such a system. But that means fighters need to be in the air or on alert nearby in order for such a concept to work.

So, the point is that passive radars have their place in an advanced integrated air defenses system. But their capabilities are limited and largely supportive in nature. As computer processing continues to improve, their ability to pick out targets from the chaos of the electromagnetic spectrum in populated areas will improve and with it so will the IADS overall capabilities. Also, moving from bistatic passive radars configurations—like TwInivs—to multi-static systems with arrays distributed across large geographical areas should also provide more robust capabilities.

Eventually, one could imagine the processing power and the complexity of these systems becoming so intricate they could get an infrared homing missile into the right area to possibly lock onto a stealthy aircraft. This would be something of a ‘holy grail’ of long-range, all passive, surface-to-air engagement where no active radar is used at all. Still, a data-link connection between the missile and the passive radar system would be needed. But the truth is that at this point the missiles that could support such an engagement are largely still in the concept stage or fielded in very limited numbers, and the passive radars capable of providing high-quality telemetry for them are largely an idea, not a reality. Also, aircraft like the F-35 have advanced missile approach warning systems that will still spot the missile heading their way and various forms of infrared countermeasures and even hard-kill systems can be employed.

Above all else, this assumes a perfect scenario and one where there are plenty of RF emissions being pumped into a sky. One way to drastically degrade these systems’ effectiveness, no matter how advanced, is to strike the commercial RF transmitters that enable them. Often times this is the first step in an air campaign anyway. In fact, many of these systems stop broadcasting during a time of war anyway.

So overall, passive radar is not a capability invalidates stealth. At least anytime soon, and likely no time in the foreseeable future, if ever. In fact, it makes stealth all that much more important as it allows aircraft to evade the radars that will be used to attack it if passive radar detects their presence.

As I have stated many times over, stealth technology is not some monolithic ‘thing’ that makes airplanes disappear. It is a wide-ranging cocktail of measures, including airframe shaping, composite structures, radar-absorbent materials, low-probability of intercept radars and communications, infrared signature attenuation, enhanced situational awareness, high-quality intelligence, mission and route planning based on that intelligence, destruction and suppression of enemy air defenses, tailored tactics employment, munitions selection, and now more than ever before, electronic warfare. All of these elements and more are balanced against performance and mission goals. Even with the best of these elements employed in the best possible way, it does not mean an aircraft is invisible to radar, it means it is far less detectable over a given range and aspect to a particular threat sensor. And just because a stealthy aircraft can be briefly detected, doesn’t mean it can be successfully engaged.

The F-35, above all other aircraft flying today, has had its traditional stealth technology backstopped with other capabilities, namely electronic warfare and enhanced situational awareness, to help ensure its survivability in many threatening scenarios it could experience in the years to come. And even today, no matter what the USAF brass proclaims in big public speeches, there are places the F-35 wouldn’t wander into without significantly degrading the enemy’s IADS fist. That’s what standoff munitions are for, which are also becoming enemy air defense network disruptors.

You can read more about the F-35’s bag of guileful survival tricks in this recent exclusive of ours.

Beyond the F-35, future combat aircraft will use very low-observable design concepts that allow it to attenuate RF energy over a far broader number of bands. This, along with advanced in radar-absorbing coatings and structures, will impact even the effectiveness of passive radar. Their self-defensive systems will be kinetic and laser-based, as well. Meaning if they do get detected, the missiles will have a hard time actually reaching their target and scoring a blow.

So no, passive radar is not something that will end the need for stealth technology, including low-observable shaping, structures, and coatings on combat aircraft. It does, however, have the potential to be an increasingly important component within any highly networked advanced integrated air defense system. It’s just another facet of the ever-increasing realm of air combat and the measures and countermeasures that it leans upon.

In the end, neither passive radar or stealth technology is magic. The truth is that the side with the best book of spells, not the single best spell, has the greatest chance of winning the air wars of the future.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com