Russia’s state environmental monitoring agency has acknowledged the presence of four radioactive substances in Severodvinsk, a city less than 20 miles from the site of a still very mysterious explosion during the test of an unspecified nuclear-powered missile. The new details continue to suggest the incident was related to the development of the nuclear-powered cruise missile Burevestnik, but they also raise further questions about how transparent the Kremlin is being about the scale of the accident that killed at least seven people.

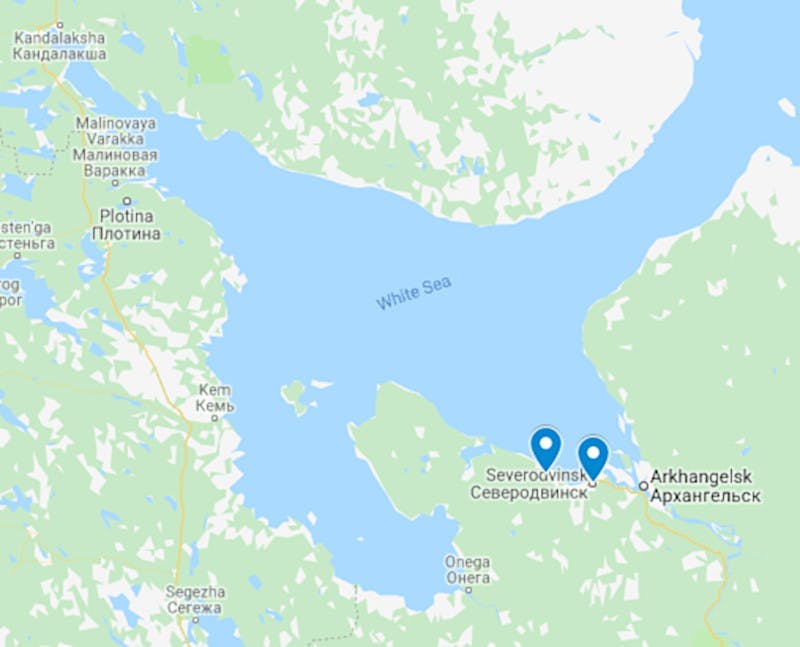

Personnel from the Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring of Russia, better known by its Russian acronym Roshydromet, took water samples from areas near Severodvinsk between Aug. 10 and Aug. 23, 2019, and found traces of the radionuclides strontium-91, barium-139, barium-140, and lanthanum-140, according to a statement. These substances experience fast radioactive decay and the press release indicated that the brief spike in ambient background radiation that Severodvinsk authorities reported after the missile test accident was attributable to inert gasses released as a result. The incident itself occured on Aug. 8, 2019, at a missile test site adjacent to the village of Nyonoksa, approximately 18 miles to the west of Severodvinsk and The War Zone

has been following the steady trickle of new information that has emerged since then very closely.

This statement would seem to contradict the Russian Ministry of Defense’s initial reports that the accident had not resulted in any radiation leaks whatsoever. Officials in Severodvinsk had subsequently retracted their statements about increased background radiation.

Since the accident, however, Russia has admitted that the system it was testing was a nuclear-powered missile and that it contained a nuclear “isotope power source” at the time of the explosion. However, Russian officials have blamed the explosion itself on a non-nuclear liquid-fueled rocket motor.

The Kremlin has publicly acknowledged the development of Burevestnik, also known to NATO as the SSC-X-9 Skyfall, but has not officially confirmed it was testing that system in Nyonoksa earlier this month. However, the evidence that has emerged so far has only continued to point more and more to this nuclear-powered cruise missile being at the center of the accident. You can read more about what is publicly known about Burevestnik and its development in these past War Zone stories.

The radionuclides that Roshydromet found strongly point to whatever the system was having a true nuclear reactor as part of its propulsion system. Experts had previously considered whether the missile might have had a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), a sort of nuclear battery that converts the heat from radioactive decay into electric power.

“These specified radionuclides rule out, to some extent, the possibility of an RTG,” Andrei Zolotkov, a Russian chemist with extensive experience with nuclear reactors from 35 years of working on the country’s nuclear icebreaker fleets, told The Guardian. “Usually, an RTG uses just one radionuclide, and during its decay, and it cannot produce these kinds of isotopes.”

Strontium-91, barium-139, barium-140, and lanthanum-140 are relatively uncommon, but could come from the operation of a nuclear reactor using a traditional nuclear fuel source, such as uranium-235. However, these types of fission reactions typically produce cesium-137, which the Russian government says it has not yet seen in elevated levels. The Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (NOSAR) said it had detected elevated levels of radioactive iodine after the accident, but could not conclusively link that to the explosion.

Zolotkov told The Guardian that the new disclosure from Roshydromet would mean that the missile contained some kind of novel reactor design or that the Kremlin is still not providing a full accounting of the situation. The former is certainly possible. For the final Burevestnik design to be reasonably small in size, it would need a highly compact nuclear reactor, which could be an experimental type itself. Some have posited that the initial reports of the missile’s propulsion system using a “liquid fuel” might be referring to a liquid fuel reactor of some kind.

At the same time, there has already been evidence that the Russians are at least trying to heavily control the flow of information surrounding the accident, if they’re not looking to cover it up entirely. There had previously been indications that the Kremlin was deliberately shutting down environmental monitoring stations that could collect further data regarding radiation leakages.

One of the doctors who treated individuals injured in the accident reportedly ended up with cesium-137 in his system, as well. Russian authorities posited that this individual had become contaminated after eating “Fukushima crabs,” a reference to seafood that might have become contaminated after the near-meltdown at the Fukushima Daini nuclear powerplant in Japan in 2011 following the catastrophic Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.

Before that, there had been unconfirmed reports of significant cesium-137 contamination at the Arkhangelsk Regional Clinical Hospital, after doctors and other staff treated patients from the accident site without receiving any warning about possible radiation exposure. A purported medical report has now leaked saying that at least one individual who came to the hospital from Nyonoksa was suffering from acute radiation sickness.

There were subsequent reports that at least 10 employees from the hospital in Arkhangelsk, along with a number of injured individuals, had then moved to the Federal Medical Biophysical Center in Moscow. There has been no clear confirmation that radiation exposure was the cause of any of the seven deaths as a result of the accident. Individuals at the site of the explosion reportedly suffered severe burns and other trauma, as well.

On Aug. 13, 2019, Russian officials had also curiously announced that they would briefly evacuate Nyonoksa the following day, before abruptly canceling that plan. It is still unclear whether that evacuation was related to the nuclear-powered missile accident or another scheduled test at Nyonoksa that subsequently got aborted.

Much about the accident itself remains unclear. Satellite imagery shows that whatever missile the Russians meant to test was on a launcher on a barge right off the coast of Nyonoksa in the White Sea. Pictures have since emerged purportedly showing extensive damage to that platform, but offering no real details beyond that about the missile itself. A second barge also appeared to be involved in the test and suffered less obvious damage.

In addition, NOSAR has also said that there appeared to be two distinct explosions and that seismic monitoring stations only detected one. It’s unclear if this might mean the second one occurred in midair, raising additional concerns about the spread of radioactive material. NOSAR also said that it is possible this second event was unrelated to the accident in Nyonoksa and might have been tied to mining activity in neighboring Finland.

The Kremlin has historically been very tight-lipped about major military accidents, and ones that involve the risk of traditional leaks, in particular. For instance, very little remains known about a separate fire aboard the top-secret nuclear spy submarine Losharik, which occurred on July 1, 2019. The boat was attached to a larger nuclear-powered mothership submarine, the modified Project 667BDRM Delfin-class ballistic missile submarine BS-64 Podmoskovye, at the time. It remains unclear how much risk there might have been to the reactors on either submarine.

At the same time, Russian authorities have found themselves increasingly compelled to release additional details about the Nyonoksa incident, the response to which has drawn repeated comparisons to the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986 in what was then Soviet Ukraine. A critically-acclaimed HBO dramatic mini-series thrust the Chernobyl case back into the public consciousness earlier this year. It also drew criticism from Russia, which says it will now produce its own show with an “honest” accounting of those events, centered on a conspiracy theory that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency was involved in its production.

In the nearly four weeks since the accident, the Kremlin has steadily disclosed additional information about the incident and has now contradicted its previous assertion that there were no radiation leaks at all, though it now maintains that the radionuclides that did escape are not a cause for concern. It will be interesting to see if and how the official line continues to evolve if it becomes any harder to deny key details about what happened in Nyonoksa.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com