Recent events have highlighted the increasing strategic value of the Arctic as both Russia and the United States seek to expand their military footprints into the northernmost regions of both hemispheres. Yet it is abundantly clear that Russia is putting huge strategic importance on the Arctic, as evidenced from its many investments in the region, while the United States lags behind in terms of a permanent footprint above the Arctic Circle.

That strategic value took center stage recently when President Donald Trump stated that his administration was considering attempting to purchase Greenland from Denmark. “It’s just something we’ve talked about,” Trump told the Wall Street Journal. “Denmark essentially owns [Greenland]. We’re very good allies with Denmark. We’ve protected Denmark like we protect large portions of the world, so the concept came up. Strategically, it’s interesting. And, we’d be interested. We’ll talk to them a little bit.”

While Trump’s comments were widely lampooned in the international press and flat out rebuffed by the Danish government, the pipe dream of purchasing an autonomous region from an ally is in fact somewhat rooted in American and NATO military policy. For over 60 years, America has operated one of its most strategic military outposts in Greenland with the permission of the Danish government.

Russia, in particular, has been increasing its air and naval power in the Arctic Circle in recent years and has been establishing new bases along what is destined to become a new and highly strategic shipping route as the ice continues to melt. NATO allies such as Denmark, with strategic arctic access to the Arctic, have thus become key to America’s defenses in what seems to be a new Cold War brewing in the Earth’s highest latitudes.

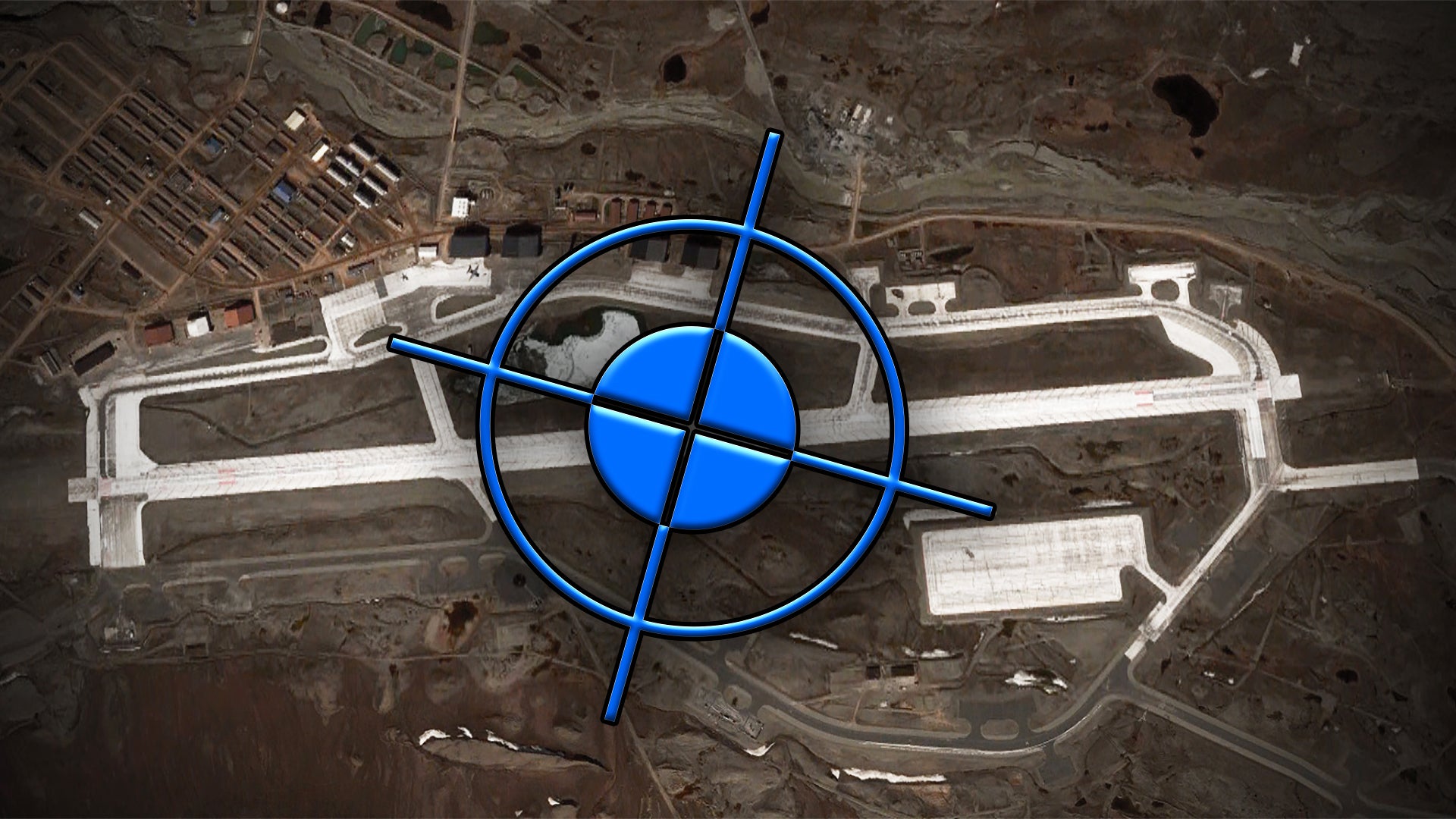

America’s northernmost military base, Thule Air Base, is key to the United States’ ability to provide early warning of an impending nuclear attack and serves as a major logistical hub in a very important, but remote region. Throughout its nearly 70-year history, the base has had many other roles and has faced its shares of challenges and near-disasters. Today, it remains just as inhospitable and vital as ever.

Thule Air Base

The United States began establishing military outposts and bases throughout Greenland after Danish Ambassador to the United States Henrik Kauffmanns made an agreement, on his own initiative and in defiance of the Danish government operating under Nazi occupation, in 1941 that authorized the United States to defend Danish settlements on Greenland from German forces. The Danish government attempted to evict the United States following World War II, but abandoned those attempts in 1949 when it joined NATO.

Because Greenland and the Arctic regions offer short distances between North America and the Soviet Union, the Cold War saw U.S. Armed Forces turn to Greenland for the establishment of early warning outpost and a locale capable of executing nuclear strikes on Russia. In 1950 the Air Force began constructing Thule Air Base in secret under the project name Operation Blue Jay. The existence of the base finally was made public in late 1952.

The installation initially featured a 10,000-foot runway, 125 barracks units, 6 mess halls, and the necessary infrastructure to support a population of thousands year-round. Other features included a hospital, power plant, and recreational facilities, including a bowling center, fitness center, and the “Top Of The World” club offering a restaurant, lounge, and ballroom. The base, which was originally operated by U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Air Command, had a multitude of missions throughout the Cold War, including supporting strategic bomber and reconnaissance operations aimed at the USSR. It even hosted interceptor jets, as well as Nike nuclear-armed surface-to-air missiles to protect it from potential attack and to swat down large formations of Soviet bombers heading to the United States would World War III have kicked off.

Today, Thule Air Base remains the United States military’s northernmost outpost, located well above the Arctic Circle and just 947 miles from the North Pole. These days, nearly 600 USAF personnel, civilian contractors, Danes, and Greenlanders still call the base home. USAF personnel assigned to Thule are welcomed to “the top of the world” with an orientation document outlining the unique challenges of living in such a remote, inhospitable environment.

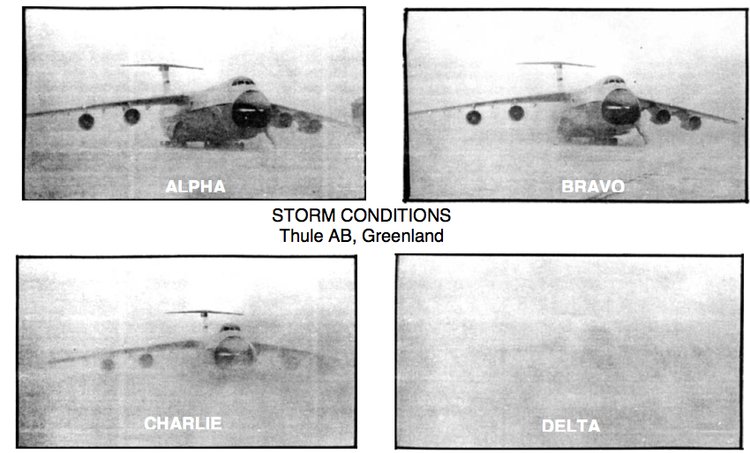

USAF personnel at Thule face winter temperatures that drop to as low as -47 degrees Fahrenheit and include winds that can peak as high as 100 knots. The closest town to the Air Base is Qaanaaq, which is located 75 miles northwest of the base and boasts a population of about 600 permanent residents. One of the most unique and arguably misery-inducing features of Thule is the fact that the base experiences constant darkness from November through February, as well as constant sunlight from May to August.

Emergency shelters are located at intervals along Thule’s network of roads, and a strict buddy system is used whenever personnel leave the base. During some storm conditions, personnel are restricted to the buildings in which they are located whenever the severe conditions are declared with no pedestrian or vehicle travel whatsoever. Frostbite, hidden pockets of water just below the snow, and snow blindness are everyday dangers faced by USAF personnel at Thule.

Thule Air Base plays host to a variety of operations, including those concerned with ballistic missile early warning and defense. Today, the Air Force’s 821st Air Base Group oversees operations at Thule. This unit is subordinate to the 21st Space Wing at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado, which provides space surveillance, missile warning, and space control to North American Aerospace Defense Command and Air Force Space Command. Detachment 1 of the 23rd Space Operations Squadron, part of the 50th Space Wing’s global satellite control network, also calls Thule Air Base home and provides telemetry, tracking, and command and control operations to the United States and allied government satellite programs.

The 821st Security Forces Squadron at Thule Air Base handles security of the 254 square-mile Thule Defense Area. That area includes a ballistic missile early warning system, satellite control and tracking facilities, the air base, and the seaport which is only accessible for a short period during the summer. The annual sealift operation to support the base during this period is called Operation Pace Goose.

Thule also hosts the 12th Space Warning Squadron, responsible for the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System which is tasked with detecting and tracking ICBMs heading for North America. A secondary mission of the 12th SWS is providing space surveillance data on satellites and other near-Earth objects like asteroids to the Joint Space Operations Center at Vandenberg Air Force Base.

The facility at Thule that primarily supports all these space and missile warning missions is Site J, or J-Site. It’s a sprawling USAF radar station that sits on a bluff roughly six miles northeast of Thule Air Base and includes some of the most up-to-date and powerful missile warning and space object tracking systems on the planet, including Raytheon’s giant AN/FPS-120 Solid State Phased Array Radar.

In the event of a missile launch threatening North America, the site will provide warnings and missile defense assessment data of incoming Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) and Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs). It is fully networked into the ecosystem of space-based, sea-based, and ground-based sensors that provide Strategic Command, and thus the National Command Authority, with critical information regarding an impending nuclear attack. Because of this high-stakes role, the information the site provides can mean the difference between identifying a mistake or accidentally ending the world as we know it.

In addition, Thule is the site of a number of flying operations, including Vigilant Shield, an annual, bi-national air defense training event staged with Canadian forces. Thule often offers support for surveillance missions, scientific data gathering flights, and as a hub for transports and search and rescue aircraft.

Over the years, it has been speculated that the base is an ideal location to launch clandestine spy flights against Russian interests in the region. Thule did play a part in the SR-71 Blackbird’s history. Tanks were installed at Thule to hold the jet’s unique JP-7 fuel and tankers did operate from there to refuel Blackbird missions, but beyond that, and being a diversion field, it isn’t clear if the base ever hosted the Blackbird. Still, one would think for secretive flying assets, the remote and strategic location with ample hangar space and a tiny population would be an ideal place to deploy them from when the mission warrants it, especially in this age of new friction between the U.S. and Russia and the latter’s designs on the region.

Because of its strategic value and early warning mission, Thule Air Base and its surrounding facilities will, unfortunately, be among the first military installations to be targeted in the event of a nuclear exchange. But the threat of nuclear annihilation isn’t the only danger Thule Air Base faces.

Ghosts of The Cold War: Camp Century and Project Iceworm

From 1959 until 1967, a secretive research facility known as Camp Century was established 150 miles east of Thule Air Base. A 1965 technical report produced by the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research & Engineering Laboratory states the facility’s official purpose was to “learn how to construct military facilities on the Greenland Ice Cap.” This was a feat which required significant research to find construction methods and materials which could survive the constantly-shifting conditions of glacial subsurface ice.

In order to provide Camp Century with power, American engineers installed a nuclear reactor under the ice, a decision which the Danish government found problematic, to say the least. There were widespread fears that the reactor could contaminate the surrounding ice sheet, but the Danish government ultimately sided with NATO deterrence policies and allowed the United States to install the nuclear reactor – and to store nuclear weapons at Camp Century.

Camp Century was known to the public, and Walter Cronkite even visited the site with CBS camera crews in 1961. However, it was also home to an infamous and bizarre research project known as Project Iceworm.

According to a 2008 study published in the Scandanavian Journal of History, Project Iceworm involved plans to construct a system of tunnels 2,500 miles in length, which could be used to launch 600 “Iceman” missiles, modified two-stage Minuteman Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs), at the Soviet Union. While this a purpose was never disclosed to the Danish public, the study’s author claims that Project Iceworm was intended to be a cornerstone of NATO’s “second strike” nuclear weapons strategy:

“According to the Army study the concept would take advantage from the remoteness of Northern Greenland, its relative closeness to Soviet targets, the ‘unique adaptability of the Icecap to nuclear deployment’, and the proximity to Thule. The key concept was to deploy the missile force in ‘thousands of miles of cut-and-cover tunnels’, or rather covered trenches, whose floor would lie 28 feet beneath the surface. The missiles would be placed some four miles apart and controlled by a total of 60 hardened Launch Control Centers (LCCs) dispersed under the ice surface. In its launch position the warhead of the Iceman would be about 3 feet beneath the surface and able to withstand an overpressure of at least 30 psi. The whole system should be launchable in 20 to 60 minutes depending on circumstances and would be relatively invulnerable ‘except to a massive Soviet thermonuclear attack’, which was not deemed likely.”

Ultimately, both Camp Century and Project Iceworm were plagued with issues stemming from the fact that the Greenland ice sheet is constantly shifting. Army engineers determined that keeping thousands of miles of ice tunnels from collapsing was too great a technical challenge and cost. Project Iceworm and Camp Century were abandoned in 1966 before the nuclear launch tunnels were ever operational, but their legacies still haunt Greenland today.

In 2016, scientists observed that rapidly melting sea ice could soon expose the buried weapons, sewage, fuel, and pollutants at Camp Century within the next 90 years. The thawing camp has been estimated to contain hundreds of thousands of gallons of diesel fuel, wastewater, radioactive coolants, and toxic organic compounds such as PCBs. These were buried in the ice along with the camp under the assumption that the ice sheet would permanently house them, but climate change is now threatening to unearth these pollutants.

Greenland, which secured home rule from Denmark in 1979 and has been increasingly more autonomous following the passage of the Self-Government Act in 2008, has unsuccessfully attempted to compel the U.S. government to clean up the abandoned outpost, but so far the base remains a contentious diplomatic issue. In 2017, the Pentagon issued a statement saying it “acknowledges the reality of climate change and the risk it poses” and will “work with the Danish government and the Greenland authorities to settle questions of mutual security.”

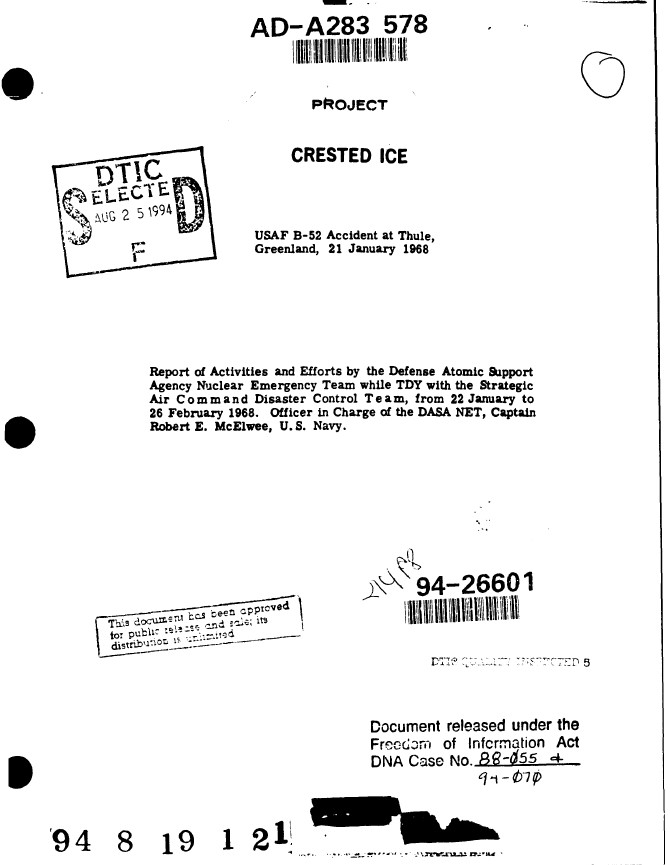

1968 B-52 Crash and Project Crested Ice

Aside from housing a ticking environmental time bomb, Thule Air Base is also the site of one of America’s worst nuclear accidents, the 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash. On January 21, 1968, a cabin fire broke out in B-52G “HOBO 28,” a USAF bomber carrying four B28FI thermonuclear gravity bombs. The cause of the fire remains unknown. Six of the seven crew members were able to successfully eject, but the seventh was killed while abandoning the aircraft. The B-52 subsequently crashed onto sea ice in North Star Bay just west of Thule Air Base.

Reports vary, but it is believed at least three of the B-52’s weapons exploded on impact, showering the surrounding area with radioactive materials. While nuclear detonations were not triggered, the conventional high explosives did, creating a swath of fallout similar to the effects of a dirty bomb. The burning fuel and explosives melted the ice sheet, allowing much of the debris to settle to the ocean floor.

The USAF quickly launched Project Crested Ice to cleanup the nuclear mess, an effort which required the collection of thousands of pieces of debris from the ice sheet and ocean floor as well as over 500 million gallons of ice water. Hundreds of USAF personnel worked for eight months in subzero temperatures to recover radioactive materials which were then shipped to South Carolina for safe disposal.

USAF documents confirm that at least 29 service members were contaminated, but a 2001 USAF evaluation of Project Crested Ice states that the highest readings in samples from contaminated personnel “were well below the annual limit of intake.”

While the clean up was deemed a success by the USAF, documents obtained by the BBC through the Freedom of Information Act suggest that at least one of the thermonuclear weapons may have been unaccounted for following Project Crested Ice.

At the time, the Pentagon refused to comment on the alleged lost weapon. A subsequent study from the state-financed Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) disputed the BBC report, saying the documents referred to a search for a part of the fissile core of one of the bombs, not a missing bomb itself.

Thule’s Lasting Strategic Importance

NATO continues to cite the Arctic as a region of “great power competition” as Russia vies for control of strategic locations and undersea natural resources. Russia has been preparing for war in the Arctic for years, and despite its foothold at Thule Air Base, the United States is still playing catch-up.

As of 2016, Russia has over 50 airfields and ports in the area, assets which may enable it to deny the United States access to the Arctic. The Russians also operate a remarkably large fleet of icebreakers across the country’s Navy and other agencies, which ensure it has access to these same areas.

China is also expanding its presence in the Arctic, prompting the Department of Defense to define the Arctic as “an increasingly competitive domain.” Earlier this year, the Pentagon warned Congress of China’s high interest in the Arctic, including Greenland, and the country’s potential to cooperate with Russia on the strategic issue. “Though Russia and China would be natural competitors for Arctic resources and influence, they have started cooperation knowing that only together they can outcompete the West,” said Agnia Grigas, an energy expert in Washington, D.C. “China’s need for energy sources and Russia’s economic dependence on fossil fuel exports depends on this.”

As the Arctic sea ice continues to melt, the world’s superpowers are racing to establish permanent footholds in the Arctic not only for military strategy but for economic development. In 2017, the Center for Contemporary Conflict wrote that there is “tremendous potential for maritime commerce” in the Arctic including oil drilling in the North Sea and the mining of rare earth metals from the sea floor.

China is already investing billions in energy extraction and minerals prospecting throughout Greenland and Siberia, and more Chinese ships are using the Northern Sea Route for commerce. Ex-NATO commander Philip Breedlove has mentioned in interviews that melting Arctic sea ice will open up new lanes for commercial shipping and maritime traffic between Asian markets and Europe and North America, meaning whichever superpower controls these lanes will be able to dictate the terms of international trade in the Arctic.

As the Arctic heats up both literally and geopolitically, Thule could become a cornerstone of America’s military strategy in what is a looming military competition in the northernmost corner of the world. Thule Air Base’s geographic location provides the United States with unparalleled access to the Arctic, and its missile detection and tracking capabilities make it one of the most strategically important sites the Air Force operates. If the U.S. wants to compete with Russia in the Arctic, Thule is likely to become a key linchpin of that strategy. Having a major installation to stage logistics out of that can then be pushed farther north will be absolutely essential in itself, as well as a place for forward-based command and control capabilities and other activities, beyond all the other support and surveillance functions the base currently provides.

This could mean that one day Thule Air Base ends up reverting back to regularly supporting strategic bomber operations—a possibility that seems even more likely as of late—and hosting a permanent cadre of fighters for its protection. Outfitting the sprawling base with static anti-aircraft and anti-ballistic missile defenses is another real possibility as tensions between the U.S., its NATO allies, and Russia continues to rise throughout the region in the coming years. The fact that the base appears to be largely defenseless at this time is quite concerning, to be honest.

With all this in mind, cooperation with the Danish government remains more imperative than ever in order to keep this site in America’s strategic portfolio, but the threat of climate change and the possibility of shifting international relationships means that this isn’t necessarily guaranteed.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com