Russia’s state-run nuclear corporation Rosatom says that a team of its employees had been working on an experimental “isotope power source” when it exploded, killing five people and injuring three more in a still very mysterious accident yesterday. The company offered no specifics about the project, but this new information, coupled with other details, suggests that this power source may be associated with a nuclear-powered cruise missile called Burevestnik that the Kremlin first announced publicly last year.

The accident occurred near the village of Nyonoksa, also written Nenoksa, in the northwestern Russian region of Arkhangelsk on Aug. 8, 2019. This is a known test site for both cruise and ballistic missiles. There have been no previous reports that Russia has previously tested Burevestnik, also known to NATO as SSC-X-9 Skyfall, which Russian President Vladimir Putin first revealed the existence of in a speech in March 2018, at this particular location. Previous reports, citing anonymous U.S. officials, indicate that the Russians had been testing this missile, details about which are extremely limited, since at least 2017, from Novaya Zemlya, a remote archipelago in Russia’s far north that has also served as a nuclear weapon testing ground.

“The tragedy happened while working with the engineering and technical support of the isotope power source in a liquid propulsion system,” Rosatom’s statement reads. “Five employees … were killed while testing a liquid propulsion system. Three of our colleagues received injuries and burns of varying severity.”

The statement does not specifically mention Burevestnik, but the general description Rosatom gave sounds similar in many ways to what is known about this weapon’s propulsion system. The cruise missile reportedly has a nuclear-powered ramjet engine that uses rocket boosters – as seen in the video of a purported previous test of the weapon below – to get it to an optimal speed. At that point, the fast-moving air would then blow over the hot reactor, before squirting out an exhaust nozzle to generate thrust.

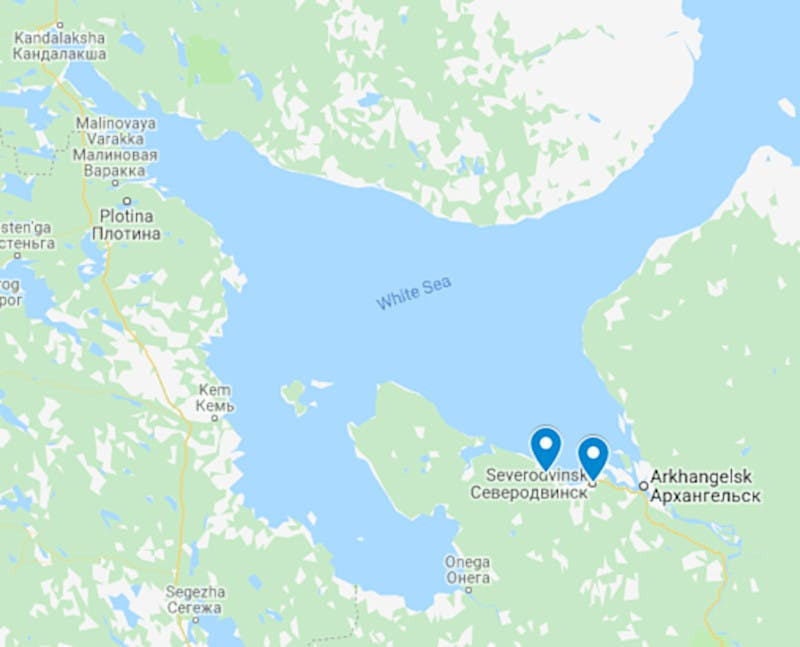

The presence of the nuclear fuel carrier ship Serebryanka in the area at the time of the accident also points to Burevestnik. This ship was reportedly part of a flotilla that Russia sent into the Arctic to reportedly recover one or more crashed Burevestniks last year. The vessel, which is configured to safely transport nuclear fuel rods and similar cargo, would be well suited to carrying nuclear-powered cruise missiles. This ship remains inside a portion of the Dvina Bay in the White Sea that the Russian government closed off to all public and commercial activity after the incident.

It’s not clear how a liquid fuel rocket motor or jet engine, the component that reportedly exploded, might fit into the Burevestnik’s design. It is possible that the system uses liquid fuel rocket boosters to get it to the necessary speeds for the ramjet to work. The incident in question may have also involved an experimental configuration with a small nuclear reactor installed, but a conventional jet engine providing actual propulsion, in order to evaluate other features ahead of full tests of the missile in a more representative configuration. Another possibility could be that this was a reference to a liquid nuclear fuel-powered reactor.

Unlike a missile using a conventional jet engine or rocket motor, the nuclear power plant could potentially keep the missile flying for weeks on end and give it virtually unlimited range, making it a nightmare for anyone trying to defend against it. Unfortunately, this also means that any test of the weapon, even one without a live warhead, still involves launching a radioactive payload. Whether or not the test fails – and crashes or explodes – or the missile succeeds in reaching its destination, it will always involve crashing a nuclear reactor into the ground or the ocean.

Of course, there remains a possibility that this incident was unrelated to Burevestnik, but this weapon is the only one that Russia has announced publicly that it is working on that involves a nuclear power source. Whatever the case, it remains worrisome that the Kremlin would be testing any such propulsion system in such relatively close proximity to population centers. Reported testing of the Burevestnik in Novaya Zemlya had made good sense.

Questions remain about how much radiation may have leaked out as a result of the accident. City officials in Severodvinsk, to the east of Nyonoksa, initially reported that there had been a brief spike in radiation based on readings of up to 20 millisieverts per hour from two sensors that are part of an automated civil defense system. Typical background radiation for the area is 0.11 millisieverts per hour. There are reports that sales of iodine, which can help prevent radiation absorption in the body, surged after the incident, though there does not to be any confirmation that officials had actually ordered residents to take it.

However, Severodvinsk authorities did say that the radiation levels had returned to normal within hours of the accident. The Russian Ministry of Defense subsequently denied any radiation leak whatsoever. Late on Aug. 8, 2019, officials in Severodvinsk pulled down the alerts about radiation that they had posted online in Russian and in English, deferring to the Ministry of Defense.

Regardless, it seems very clear that there was at least some release of radiation. The Norweigan Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, also known by the acronym DSA, which has a close working relationship with its counterparts in Russia, issued its own statement on Aug. 9, 2019, to say that it had received reports about a radiation leak, but noted that it had not detected any increased radiation from its own sensors.

“Six persons are receiving treatment [in Russia] after receiving higher doses of radiation,” the statement noted, though it does not say if any of them had died from the exposure. “No increased levels of radioactivity has [sic] been found, but the DSA will continue to monitor.”

Pictures and video of Russian personnel in protective gear screening helicopters bringing in the wounded and ambulance drivers taking similar precautions as they took the individuals to a local hospital would certainly seem to imply that they had sustained significant radiation exposure. This could also have been standard precautions given the radiological nature of the incident.

If a Burevestnik missile, or a test article related to that weapon’s development, was involved in the accident, it is not clear how the incident might impact the program going forward. Previous reports, citing unnamed U.S. government officials, had said that the program had suffered numerous failures already.

How serious Russia is or isn’t about the missile, and how viable a weapon it could ever be at all, remains up for debate. The Kremlin has stressed in the past that Burevestnik does not fall under the terms of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, with the United States, but it has also indicated that it might be willing to include it in a revised or all-new agreement. This raises the possibility that Russia may have begun development of this high-risk system, along with a similarly controversial nuclear-powered torpedo called Poseidon, at least in part, simply so it could offer to end the program in return for concessions from the U.S. government in future arms control negotiations.

Whatever happens, it will certainly be interesting to see what, if any, additional information the Kremlin might release about this incident going forward now that an arm of the Russian government has gone on the record to admit to the accident at least tangentially involved radioactive material.

Update: 8/10/2019—

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), which monitors compliance with this agreement prohibiting nuclear explosions for any purpose, has issued a statement saying that they detected the incident coinciding with the accident at Nyonoksa seismically and via infrasound. However, they did not say that they believed what they had detected was a nuclear weapon detonating.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com