France is eying a constellation of miniature space-based guardians armed with lasers that could strike at other satellites if the country’s orbital assets come under attack, along with increased surveillance capabilities in orbit to spot potential threats. There are many questions about the potential plan that remain unanswered, but that the French are considering it at all highlights growing concerns about potential conflicts in space and the reality that no one necessarily knows what that might actually entail.

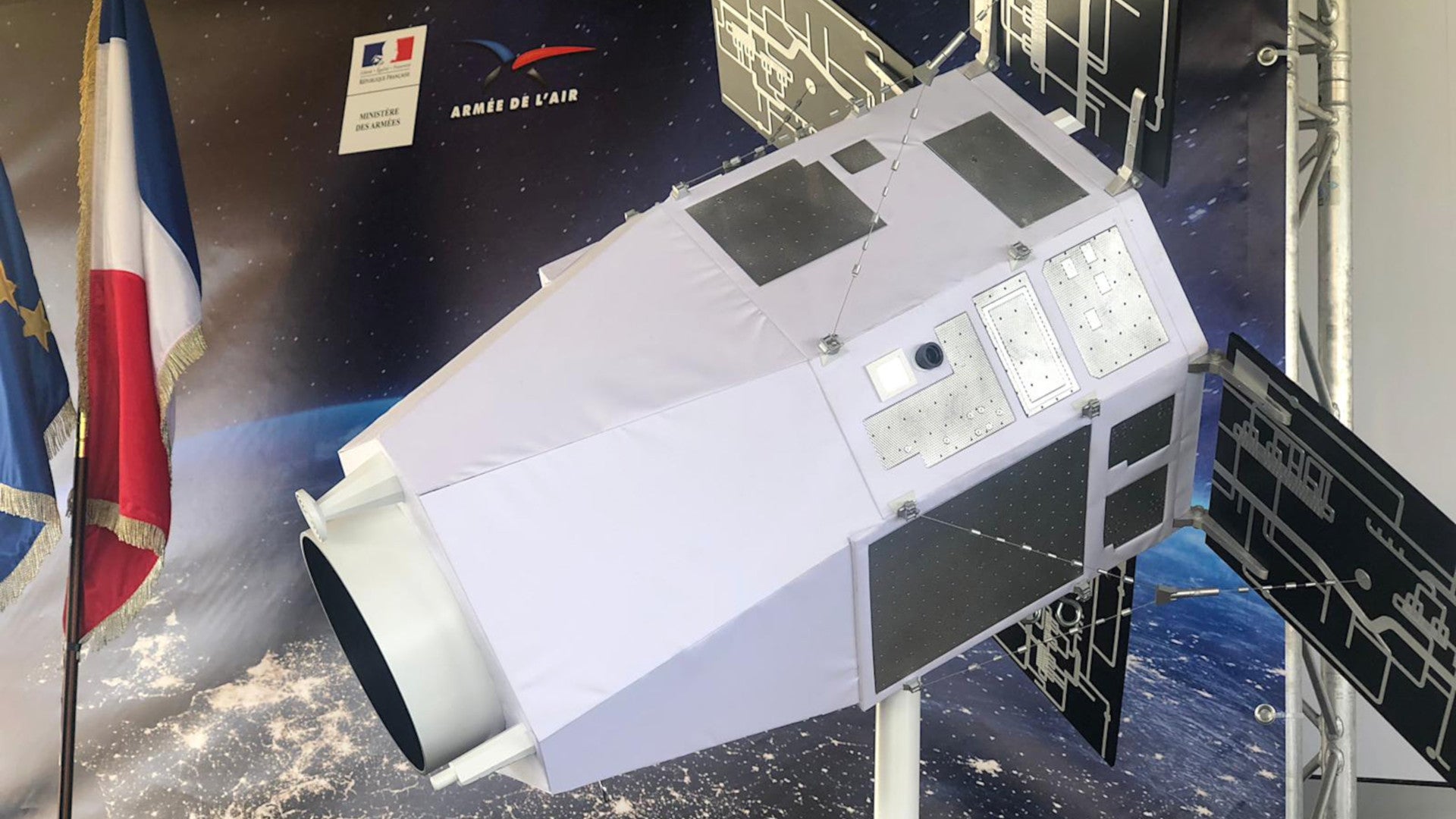

France’s Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly described to reporters on July 25, 2019, the country’s new “Mastering Space” plan to boost surveillance capabilities in space to spot potential threats and to develop an active defense posture to respond to any attacks. Parly also announced that the country would expand space-related defense spending by $780 million through 2025, on top of an existing budget of around $4 billion over the next six years. This came just weeks after French President Emmanuel Macron announced that the country would create a Space Command within the French Air Force by Sept. 1, 2019. That service will subsequently get renamed the Air and Space Force, as well.

“Today our allies and our military adversaries are militarizing space,” Parly said. “We must act. We must be ready.”

Parly offered limited specifics about how France planned to pursue the surveillance and active defense components of the Mastering Space effort. By far, the biggest reveal was that the French could potentially deploy a constellation of dedicated laser-armed mini-satellites to guard other assets, which the country could begin buying in numbers as early as 2023.

“If our satellites are threatened, we intend to blind those of our adversaries,” Parly declared said. “We reserve the right and the means to be able to respond: that could imply the use of powerful lasers deployed from our satellites or from patrolling nano-satellites.”

It’s not clear whether these laser attacks would be directed at attacking satellites or simply any other satellites belonging to the hostile party that initiated the skirmish. In addition, Parly only mentions “blinding” satellites, but this would only work against the optics on a target satellite. She also did not say whether such an attack would be aimed a permanently disabling a target’s cameras or merely at “dazzling” them temporarily

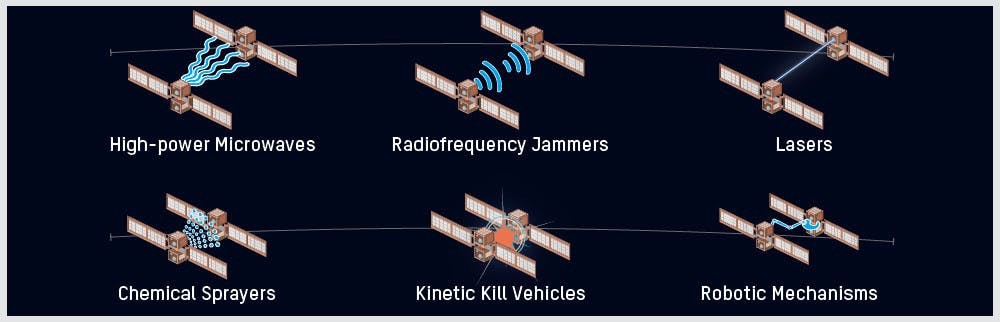

She did say that France was developing high-powered laser directed energy weapons – “an area in which France has fallen behind” – to support this project. This might potentially point to a broader ability to damage or destroy other space-based assets in the future. The U.S. military, almost certainly the main “ally” Parly was referring to as militarizing space, is already pursuing space-based lasers, microwave beams, and particle beams, ostensibly for missile defense, but that could similarly have a role in targeting hostile satellites.

Parly’s comments also come amid growing concerns about Russia’s increasing number of small, very maneuverable “killer satellites” in orbit that might be able to use small manipulator arms to physically attack other objects in space or simply smash into them in order to destroy them. They are also small enough to possibly position themselves close to otherwise satellites and remain undetected until the time comes to strike or hide in fields of otherwise innocuous “space junk” floating in orbit, making them difficult to monitor.

It’s worth noting that these same tiny satellites might carry electronic intelligence equipment, electronic warfare jammers, or directed energy weapons that might be able to blind optics or otherwise interfere with a satellite’s operation, too. Even just having some sort of sprayer to paint over cameras or solar panels could be enough to achieve a mission kill on a particular target.

In 2018, Parly publicly accused Russia of using one of its Luch-Olymp relay satellites to try and maneuver close to Athena-Fidus military communications satellite, which France and Italy operate jointly, to try and intercept transmissions. It got “so close that one really could believe that it was trying to capture our communications,” she said at the time.

Beyond space-based threats, there are also a growing number of terrestrial anti-satellite threats, including ground-based interceptors, too. In March 2019, India conducted its first-ever anti-satellite weapon test. The United States, Russia, and China are the only other countries to have demonstrated surface-launched anti-satellite weapons.

In order to help better monitor for these sorts of potential threats in the first place, Parly said that France would also be adding surveillance cameras to its Syracuse military communications satellites. However, it was unclear how France would be able to make these modifications to the elements of that constellation that are already in orbit or if this would only apply to future Syracuse 4 satellites.

Two of these, Syracuse 4A and 4B, are already under construction, with the first one slated to be in orbit and operating in 2021. In November 2018, French authorities announced that they had decided to procure a third Syracuse 4 satellite, as well. The Syracuse 4 design reportedly has additional protective features to harden it against cyber attacks, electronic warfare jamming, and electromagnetic pulses.

France is also looking to develop a successor to Graves radar surveillance satellite, which already provides enhanced situational awareness about activity in space. “The successor of Graves must be able to detect satellites 1,500 kilometers [932 miles] away that are no bigger than a shoe-box,” Parly said.

But however the French decide to increase monitoring of its existing satellites, especially to watch out for potentially hostile mini-sats maneuvering close to them, and what steps they take to develop capabilities to attack those threats, serious questions remain about just what exactly a conflict in space might look like at all.

Parly’s comments, and their lack of specifics, in many ways reflect similar statements from former Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson and U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein earlier in 2019, which The War Zone

analyzed in detail at the time. Wilson and Goldfien both spoke about the potential development of active defensive measures to protect American space-based assets, but offered little explanation about how it might implement any such response.

Attributing attacks in space, especially against satellites a country may not even acknowledge exist, can be difficult, to begin with. Deciding what a proportional response would be, particularly given that a skirmish in space is unlikely to produce immediate human casualties, might be even more problematic and could easily lead to an escalating conflict that extends down to terrestrial battlefields.

“It’s really difficult to go ahead and justify how you might attack somebody’s homeland if they’ve taken out a satellite that you don’t even admit exists,” Douglas Loverro, then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, said during a talk in 2016. “Is jamming an attack? Is a laser an attack? Does it have to be a kinetic hit on a satellite to be an attack?”

“None of us actually know how a war – if and when it extends to space – will actually evolve, where and what phase will it happen, when will it happen in the conflict, how will it be engineered, we don’t know any of that,” he continued. “Probably people are going to die on the ground where nobody’s going to die in space.”

Despite the very real concern of a potential clash in space, or at attacks on space-based assets as part of a broader conflict above and below the earth’s atmosphere, three years after Loverro outlined these issues, not much has changed in the way of policy and international norms. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty bans signatories from placing weapons of mass destruction, such as nuclear weapons, in space, and prohibits them from militarizing the moon and other “celestial bodies,” but does not restrict the deployment of conventional space-based weapons or other military capabilities.

As space becomes more crowded – approximately 2,000 active satellites are in orbit right now and this doesn’t include inactive “space junk” that poses its own hazards – these questions will only become more pressing. In June 2019, India notably announced plans to conduct a table-top “space war” exercise the following month that would explore many of the same issues.

“We are not afraid of everyone,” Parly said in response to a question at the press conference on July 25 about whether France’s new space policy was directed at any potential adversaries in particular. “We consider because we’ve seen it that space is becoming a potential place of conflict.”

This is certainly true, but it remains less clear what character a conflict in space might take on and how exactly a future full of space-based weapons, such as France’s proposed laser-toting miniature satellites, might shape it before, during, and after it occurs.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com