The U.S. government is auctioning off the former USAV SSGT Robert T. Kuroda, one of the eight General Frank S. Besson-class Logistics Support Vessels, or LSVs, which V.T. Halter Marine built for the U.S. Army between the 1980s and the early 2000s. The General Services Administration says it expects to sell off another LSV, along with dozens of other landing craft, tugs, and other Army maritime assets by the end of 2020. This is in line with reports earlier this year that the service has decided to gut its already unappreciated maritime capabilities, which could easily prove to be short-sighted given the value of these vessels, especially with regards to a potential conflict and the Pacific region.

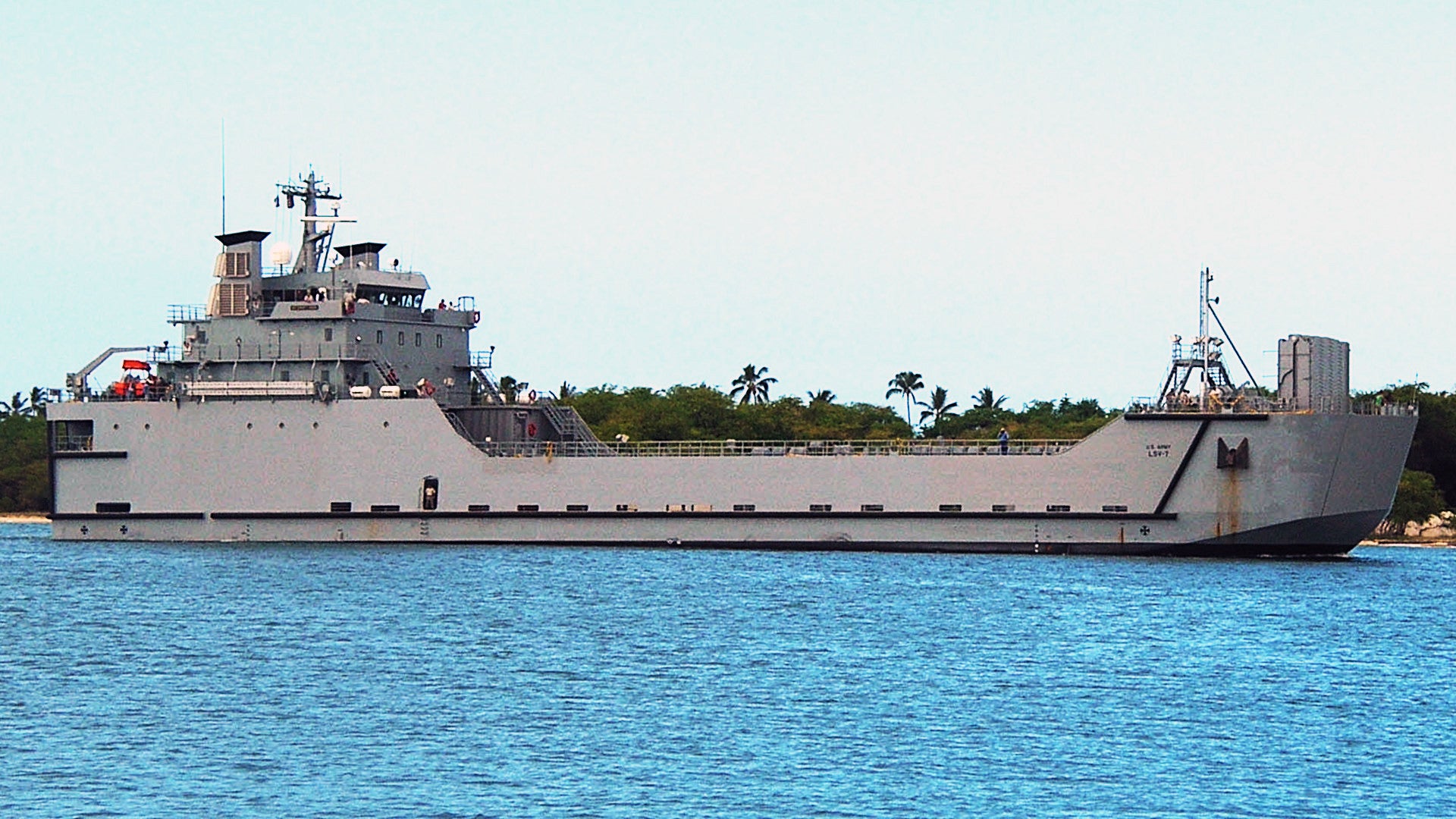

The former Kuroda, also known by the hull number LSV-7, which displaces 6,000 tons, first appeared on the General Services Administration’s (GSA) official auction site earlier in July 2019 and the auction ends on July 31. The ship is presently pier-side in Tacoma, Washington, and one can contact the Army to schedule an in-person inspection. At the time of writing, someone had bid $1 million for the vessel, though this has not met an unspecified reserve price for the ship, which originally cost $26 million to build. You can read more about the LSVs in detail in this past profile of these ships at The War Zone.

Kuroda had entered Army service in 2006, making her a relatively young ship. She is the second to last of the General Frank S. Besson-class and, along with her sister ship USAV Major General Robert Smalls, or LSV-8, it is part of a small subclass.

These two LSVs are 1,800 tons heavier than their cousins, primarily on account of a longer, more hydrodynamic bow. They also have double the horsepower of the earlier ships, the ability to generate large quantities of fresh water, and otherwise feature an expanded design with better living conditions for longer-duration operations. These capabilities, together with a range of 6,500 miles, meant they were better suited to responding to crises farther from their home ports, especially across the vast expanses of the Pacific.

The Army’s LSVs, in general, represent the top-tier of the service’s obscure maritime capabilities, which are often referred to as the Army’s Navy. This allows the service to not necessarily have to call on the U.S. Navy or chartered ships in order to move personnel and materiel by sea. This, in turn, also eases the burdens on the Navy, which has seen its amphibious and sealift capabilities increasingly stretched thin already.

The LSVs, which have front- and rear-mounted ramps to rapidly unload vehicles, including tanks and other heavy armor, and other cargo straight onto beaches, can also support a wide variety of important non-combat missions, including aid in the response to major natural disasters. They’re also ideal for moving oversized cargo. In 2009, Kuroda transported a C-17A Globemaster III aircraft fuselage, which was destined to become a training aid, from Seal Beach in California to Fort Lee in Virginia, highlighting both its load-carrying and long-distance capabilities.

So, it had already come as something of a shock when it emerged in January 2019 that the Army had decided, seemingly out of nowhere, to divest a significant portion of its watercraft fleets. Publicly, the Army has described the effort as limited to “Reserve Component” units, which includes the Army Reserve and National Guard, and as being a “right-sizing” of its maritime capabilities in order to free up funding for other priorities.

“This will be a long-term process as we review all aspects of Army watercraft employment,” Cheryle Rivas, an Army spokesperson, told The War Zone by Email in January. “The Army watercraft force that emerges will be more ready and capable of meeting the National Defense Strategy and combatant commander requirements.”

However, it remains unclear exactly how the Army arrived at this decision in the first place and, by all indications, it came as a surprise to the units affected, too. “A lot of things are happening a lot faster than we’re prepared for,” Chief Warrant Officer 2 Brandon Redmon, a spokesman for the U.S. Army Reserve Center in Morehead City, North Carolina told the Carteret County News-Times in April 2019.

This mirrors the comments that U.S. Army Major David Finn, the Chief Force Manager for the Army Reserve’s 377th Theater Sustainment Command, made during a briefing on the divestment plan in January 2019, which The War Zone subsequently obtained. Finn’s briefing says that the decision was made outside of routine Army Structure memorandums, or ARSTRUCs, and that, at that time, there were still no written orders from the Department of the Army’s top headquarters, or HQDA, to inactivate Reserve watercraft units, despite separate instructions to have them shut down completely by September 2019.

“The ARSTRUC reflect changes to the force that are a result of critical analysis conducted during the Total Army Analysis (TAA) process,” Finn wrote in the notes accompanying the PowerPoint presentation. “Usually an in-activation is identified in the ARSTRUC between 2-5 years prior to EDATE [Effective Date of the inactivation].”

The decision to sell off Kuroda, one of the two youngest and most capable LSVs, only further calls into question what kind of watercraft capabilities, if any, the service is truly interested in retaining. GSA’s announcement that it could auction a second LSV might point to the Army planning to get rid of Smalls, as well.

A banner advertisement on GSA’s auction website also says that it expects to sell 18 LCU-2000 and up to 36 LCM-8 landing craft, along with 20 tugs and a pair of floating crane barges, between now and the end of next year. The divestment of the LCM-8s makes some sense, given the Army awarded a contract worth nearly $1 billion in 2017 to buy all new Maneuver Support Vessels (Light), or MSV(L)s, to replace these Vietnam War-era landing craft.

But divesting 18 of the larger LCU-2000s would mean cutting more than half of the Army’s current fleet of those landing craft. The plan, at least according to GSA’s ad, involves getting rid of all of the service’s tugs, too. Three tugs and one of the crane barges are already listed on the GSA Auctions website.

These divestments would go well beyond simply shutting down watercraft units in the Army Reserve. There are only seven LCU-2000s and eight tugs in Reserve Component units. The rest of these watercraft are either in Active Component Army units or in prepositioned stockpiles around the world, meant to be in place and available on short notice specifically in case of unforeseen contingencies.

Whatever the origins of the decision were and what the Army’s exact plans for its watercraft fleets are now, it seems clear that the service is rapidly moving to significantly scale back its maritime capabilities. It’s a decision that it could easily come to regret, especially as the U.S. military as a whole is supposed to be increasing its capabilities with a particular eye toward a potential conflict in the Pacific region.

The “tyranny of distance” in the Pacific inherently means that Army units could easily find themselves scattered across a broad area thousands of miles from established logistics hubs. Organic watercraft able to move personnel, vehicles, equipment, and supplies around such a theater of operations without necessarily having to wait for support from the Navy or private contractors could be extremely valuable. They would also offer added capacity to move cargoes from larger ships ashore and within littoral areas, such as between islands within a chain.

The watercraft can also provide more novel capabilities, including carrying artillery pieces and acting as mobile fire support platforms. The Army’s Navy would also be able to free up Navy ships for more demanding missions and provide added operational flexibility all around.

The Army’s divestment plan also comes amid a recent spike in tensions between the United States and Iran. Army watercraft have long been forward deployed in the region for years to provide valuable support to operations in the Persian Gulf and other Middle Eastern littorals. Beyond that, Army ships and smaller boats continue to be important tools for responding to natural disasters at home and abroad.

Army watercraft units are staffed with uniquely trained mariners who may need significant retraining before taking on other roles. Given the high number of Reservists impacted, it may simply be hard to retain those individuals at all if they lose the vehicles that are intrinsic to their specialized training. This lost knowledge base could make it particularly difficult to reconstitute these capabilities in the future.

Unfortunately, with the former Kuroda and the other Army ships already up for sale, and GSA touting that there are dozens more to come, the service’s decision to severely downsize its watercraft capabilities may be one that is hard to reverse. For anyone in the market for any of these still very capable ships and smaller craft, now seems to be the time to start watching the government’s auction website.

UPDATE: 7/12/2019—

At some point after the publication of this story, the listing for USAV SSGT Robert T. Kuroda disappeared from the GSA Auctions website, despite the auction period have been listed as ending on July 31, 2019. A representative at the auction site’s help desk hotline told The War Zone that the entity who had made the item available for sale in the first place, the U.S. Army, in this case, would have been responsible for delisting the item, but had no further information.

We have since reached out to the Army to inquire as to why they took down the listing for Kuroda, but have not yet heard back. In addition, the banner advertisement promoting the “Army Vessel Sale” was still up at the time of writing and one large tug, two small tugs, and the crane barge were still listed on the auction site.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com