Recently, new details have emerged regarding a series of still unexplained encounters that U.S. Navy F/A-18 Super Hornet pilots had with unidentified flying objects while conducting training missions off the East Coast of the United States in 2014 and 2015. The War Zone has already explored this new report in detail and looked at how improved radars had played a major role in detecting these objects. But what wasn’t immediately apparent was just how ideal the situation could have been during at least some of these incidents for observing and recording the performance and signatures of potentially revolutionary flying machines under real-world conditions by the very best combined group of air defense assets on the planet.

The aircraft and ships present around the time these events occurred were equipped with the most advanced sensor fusion, networking, and computer processing capabilities available. In fact, collectively they represented the first time these capabilities were deployed across an operational Carrier Strike Group. This directly mirrors the peculiar conditions present during the famous “Tic Tac” incident involving the USS Nimitz, her air wing, and her escorts off the Baja Coast in 2004.

Prior to the latest revelations regarding encounters with Navy pilots that occurred just a couple of years ago, we dug deep into the 2004 Nimitz event, as well as the greater issues surrounding the topic and its strange resurgence within the Pentagon, in this expose which you should read for better context of the information we are about to present below.

Author’s note/update: People are asking a lot of questions that are answered in the pieces linked above. Reading them is essential to understanding the full situation and the many variables and issues at play when it comes to this complex and quickly developing topic.

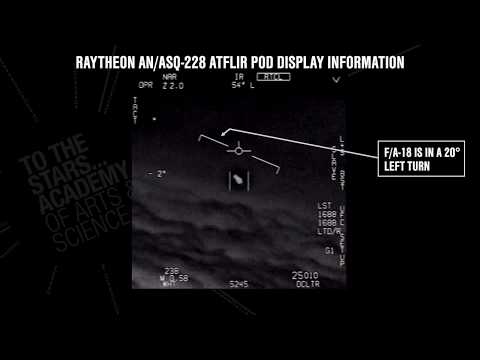

On May 26, 2019, The New York Times dropped the new details, sourced in part from on the record interviews with two Navy fighter pilots from VFA-11 Red Rippers – Lieutenants Ryan Graves and Danny Accoin – as well as off the record comments from three more aviators. Broader information about the events from 2014 and 2015 has been passed around as random facts and rumor for some time and the famous “gimbal video” is reportedly from one of these encounters, but the Times piece offers hugely significant additional context with actual names attached to it.

“People have seen strange stuff in military aircraft for decades,” Graves told the Times. “We’re doing this very complex mission, to go from 30,000 feet, diving down. It would be a pretty big deal to have something up there.”

But the Times‘ story doesn’t mention that between 2014 and 2015, Graves and Accoin, and all the other personnel assigned to Carrier Air Wing One (CVW-1) and the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, as well as everyone else in the associated carrier strike group, or CSG, were taking part in series of particularly significant exercises. The carrier had only returned to the fleet after major four-year-long overhaul, also known as a Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH), in August 2013. This process included installing various upgrades, such as systems associated with the latest operational iteration of the Navy’s Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC) and its embedded Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA) architecture.

This is a critical detail. When the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group encountered the Tic Tac in 2004, it was in the midst of the first ever CSG-level operations of the initial iteration of the CEC.

Regular readers of The War Zone will be well aware of these systems and we recently provided the following detailed explanation of their capabilities as part of the aforementioned in-depth expose regarding unidentified flying objects, their potential origins, and Pentagon’s sudden change in willingness to discuss them:

“At its very basic level, it [CEC] uses the Strike Group’s diverse and powerful surveillance sensors, including the SPY-1 radars on Aegis Combat System-equipped cruisers and destroyers, as well as the E-2 Hawkeye’s radar picture from on high, and fuses that information into a common ‘picture’ via data-links and advanced computer processing. This, in turn, provides very high fidelity ‘tracks’ of targets thanks to telemetry from various sensors operating at different bands and looking at the same target from different aspects and at different ranges.

Whereas a stealthy aircraft or one employing electronic warfare may start to disappear on a cruiser’s radar as it is viewing the aircraft from the surface of the Earth and from one angle, it may still be very solid on the E-2 Hawkeye’s radar that is orbiting at 25,000 feet and a hundred miles away from the cruiser. With CEC, the target will remain steady on both platform’s CEC enabled screens as they are seeing fused data from both sources and likely many others as well.

We are talking about a quantum leap in capability and fidelity here folks.

The data-link connectivity and the quality of the enhanced telemetry means that weapons platforms, such as ships and aircraft, could also fire on targets without needing to use their own sensor data. For instance, a cruiser could fire a missile at a low-flying aircraft that is being tracked by a Hawkeye and an F/A-18 even though it doesn’t show up on their own scopes.

This capability continues to evolve and mature today and will be the linchpin of any peer-state naval battle of the future that the U.S. is involved with. But back in 2004, it was new and untested on the scale presented by the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group as it churned through the warning areas off the Baja Coast.

The key takeaway here is that if ever there was an opportune time to capture the very best real-world sensor data on a high-performance target in near lab-like controlled settings offered by the restricted airspace off the Baja Coast, this was it. And by intention or chance, this is exactly what happened.

Beyond the greatly enhanced fidelity of the overall situational ‘picture,’ CEC provides via sensor fusion across a wide array of disparate platforms spread out over a large area, the NIFC-CA part of it enables an impressive amount of targeting-quality data sharing between Navy ships and aircraft. This, in turn, opens up a new range of tactical possibilities. For instance, it enhances the ability to engage opponents using remotely-launched weapons.

As an example, the cruiser or destroyers in a CSG could fire SM-6 surface-to-air missiles at targets outside of the range or below the radar horizon of their own sensors by using the radar telemetry from one of the carrier’s Super Hornets flying far forward of the vessel’s location. In another scenario, an E-2D could feed targeting information to Super Hornets to allow them to fire beyond-visual-range air-to-air missiles at opponents without having to activate their own radars.

CEC/NIFC-CA is truly an amazing and important set of capabilities that have been in development for decades.

Between August 2013 and August 2014, the Theodore

Roosevelt supported flight tests of Northrop Grumman’s experimental X-47B unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV). But at the same time, the Navy was moving toward preparing the entire Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group, including CVW-1, to become the first ever to deploy operationally with CEC/NIFC-CA functionality.

The Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group’s encounters with UFOs only began toward the end of 2014, according to the Times. This is around when CVW-1’s Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron One Two Five (VAW-125), the “Tigertails,” became the very first to fly the latest E-2D Advanced Hawkeye, which is a core component of the Navy’s NIFC-CA/CEC plans. A hugely powerful upgrade of the venerable E-2C Hawkeye, the E-2D also has additional, still-classified electronic support measures and networking capabilities.

In January 2015, the CSG as a whole, including CVW-1 and the Ticonderoga-class cruiser USS Normandy, which had also received upgrades to add in CEC/NIFC-CA capabilities, entered a process known as a Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX) ahead of its deployment.

“[COMPTUEX] is designed to replicate real-world combat scenarios that can potentially present themselves to our strike group at any time during a deployment,” U.S. Navy Captain Scott F. Robertson, Normandy‘s commanding officer at the time, said in a statement in January 2015. “We are going to experience real combat situations from all angles, there will be training evaluations from a hostile ship boarding, submarine attacks, and enemy ships or vessels trying impede their justice upon our strike group.”

Of course, we don’t know how close any of the CSG’s other assets were when Graves and Accoin, or their unnamed wingmen, actually encountered the UFOs. We also don’t know if any of these incidents occurred during the COMPUTEX period specifically, but the ships and aircraft had been conducting other training activities together for months already at that point and continued to operate together afterward.

Still, it’s hard to overstress just how opportune the conditions would have been for this particular CSG, or elements of it, equipped with the world’s best air defense capabilities to be tested against exotic and high-performance flying craft.

It is also curious that sightings of these objects would coincide with the first major deployment of the CEC/NIFC-CA architecture and the E-2D Hawkeye and then more would occur around the time of the Strike Group’s work up to the first operational deployment of those systems. It is entirely possible that this was all just a coincidence, but it would be a particularly amazing one if that was the case, especially as it directly mirrors the situation and conditions in which the Tic Tac incident took place with the Nimitz CSG a decade earlier.

We have to stress that all this doesn’t definitively mean these objects belong to the United States Government or that their presence was directed or

expected by the powers that be, but this revelation adds to the likelihood of those possibilities.

Contact the authors: Tyler@thedrive.com and jtrevithickpr@gmail.com