The U.S. government says that Russia may be conducting low-yield nuclear testing at a remote site above the Arctic Circle in violation of its obligations under the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, or CTBT. The allegation comes at a time when arms control deals between the two countries appear especially fragile. At the same time, the two nuclear-armed nations are actively working to modernize and diversify their arsenals.

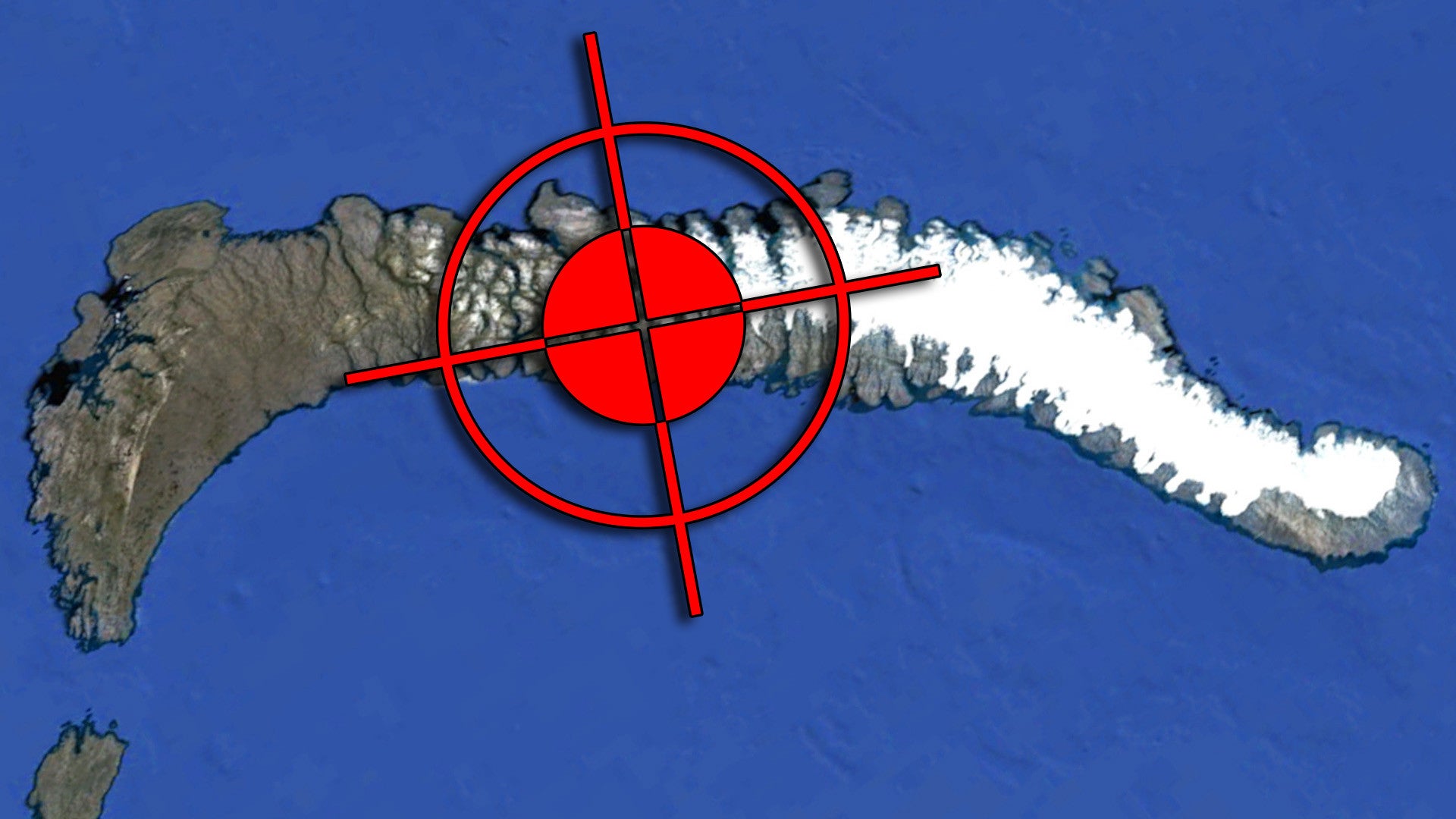

The Wall Street Journal was first to report the accusation on May 29, 2019, citing a U.S. intelligence assessment and comments from U.S. Army Lieutenant General Robert Ashley, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). The claims reportedly center around activities at Novaya Zemlya, an archipelago in Russia’s far north, where the country has conducted nuclear weapon testing in the past and that continues to support nuclear weapons development programs.

“The United States believes that Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard,” DIA Director Ashley said in prepared remarks at the Hudson Institute think tank in Washington, D.C. on May 29, 2019. “We believe they have the capability to do it, the way that they’re set up.”

It is important to note, however, that he declined to offer any additional specifics and would not confirm whether the Russians had actually conducted any low-yield nuclear tests, despite the purported ability to do so. The Russian Embassy in Washington also denied to the Journal that the country had violated the CTBT.

Russia signed the CTBT in 1996 and ratified it in 2000. The United States signed the agreement in 1996, but has never ratified it. However, the U.S. government has been observing a self-imposed moratorium on all nuclear testing since 1992. These agreements and declarations were the outgrowths of decades of negotiations dating back to the first-ever nuclear test in New Mexico, known as Trinity. These discussions between nuclear-armed powers had also resulted in the Partial Test Ban Treaty, or PTBT, in 1963, in which signatories agreed not to detonate nuclear weapons above-ground, undersea, or in space.

The video below offers an excellent graphical representation of the extent of known nuclear testing, covering detonations between 1945 and 1998.

In addition to obtaining details about the new intelligence assessment about possible Russian nuclear testing, the Journal says it has seen an unreleased 1997 presidential directive from then-President Bill Clinton. This document explains that the United States and Russia, as well as with the United Kingdom, France, and China, all exchanged letters agreeing that certain unspecified activities were exempt from the parameters of the CTBT.

The treaty continues to lack a hard technical definition of what constitutes a nuclear explosion. It also allows for computer modeling and other non-nuclear testing related to nuclear weapons so that countries can ensure the safety and reliability of their nuclear stockpiles.

With all this in mind, it is unclear whether or not the U.S. government is actually accusing the Russians of test firing low-yield nuclear weapons or if it is asserting that the Kremlin is not keeping with the spirit of the agreement and is exploiting technical loopholes in the CTBT to achieve the same research and development aims. For instance, evidence emerged in 2012 that Russia might have constructed a new sub-critical nuclear test facility in Novaya Zemlya.

But sub-critical testing, which does not involve a full-fledged nuclear reaction, does not meet the threshold of a nuclear explosion under the CTBT, according to either Russia or the United States. The U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration operates a similar facility, known as the U1a Complex, within the Nevada National Security Site for exactly this purpose.

It’s also almost impossible to independently assess the new U.S. government claims without any details about the intelligence sources the U.S. government is using to make its determination about potential Russian low-yield testing. This could include a mix of intercepted communications, human intelligence, atmospheric testing, geological monitoring, and more.

In 2017, there were curious and still largely unexplained reports about increased levels of radioactive isotopes in the atmosphere in Europe, which civilian researchers traced back to northwestern Russia. This also appeared to prompt the U.S. Air Force to deploy one of its WC-135 Constant Phoenix atmospheric testing aircraft to the region, though the service denied it was in response to any particular event.

Reports have since emerged that the U.S. government has been monitoring Russia’s tests of its still-in-development nuclear-powered Burevestnik cruise missile, which the Kremlin says will be nuclear capable. These launches have occurred from Novaya Zemlya and would, by definition, involve a nuclear reactor smashing into the ground at the end of each test, whether it is successful or not. It is possible that these events could produce signatures similar to extremely low yield nuclear testing.

There is the potential for other kinds of false positives, too. In 1997, the U.S. government accused the Russians of violating then still relatively new CTBT with a test in Novaya Zemlya, which turned out to have been a benign earthquake. Still, the United States has re-raised concerns about possible Russian low-yield nuclear testing since then and has cited it as a reason for not ratifying the CTBT in its present form.

There are also questions about what value extremely low-yield nuclear testing, which would have to involve detonations small enough not to draw the public attention of civilian government agencies and researchers who also monitor for such things. “Our understanding of nuclear weapon development leads us to believe Russia’s testing activities would help it to improve its nuclear weapons capabilities,” Ashley said at the Hudson Institute.

“It would be unfortunate if they were doing something at Novaya Zemlya that was not in the spirit of a zero-yield CTBT,” Siegfried Hecker, who served as the director of the U.S. government’s Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1986 until 1997, told the Journal. “But would the Russians somehow be able to gain an advantage for new systems if they were doing something slightly more than that? My general sense is no.”

But none of this necessarily means the Russians might not see some value in such tests or that they have laid the groundwork for more serious testing if it were to become obvious that the U.S. government was looking to pull out of the CTBT entirely. The Trump Administration insists it has no plans to abandon the treaty and resume nuclear testing, but in 2018 the President instructed the Department of Energy to be ready to detonate a nuclear device within six months of getting the order. The previous requirement was for the department to be able to resume testing within two to three years.

“The United States will not seek Senate ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, but will continue to observe a nuclear test moratorium that began in 1992,” the Pentagon said in its most recent Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which came out in 2018, a notable change in the phrasing from the previous NPR. “This posture was adopted with the understanding that the United States must remain ready to resume nuclear testing if necessary to meet severe technological or geopolitical challenges.”

Since Trump took office in 2017, there have been growing calls for the United States to resume nuclear testing to support programs to modernize the country’s nuclear arsenal. This effort, which is costing hundreds of billions of dollars, began under President Barack Obama, but has grown even larger under the Trump Administration.

Regardless of whether Russia is or isn’t conducting secret low-yield nuclear testing, or is preparing to do so in response to the United States doing the same, a dispute over the CTBT is the latest in a worrying trend regarding major arms control agreements. Last year, the Trump Administration announced it would abandon the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, over the Kremlin’s violations of that deal, which you can read about in more detail here. There are now questions as to whether the U.S. government will look to extend the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, due to a host of issues you can find out more about here.

There are already strong indications that the United States and Russia, and potentially other nuclear powers around the world, are already in the midst of a new arms race. If the CTBT were to completely collapse, it could only further inflame the situation. That is to say nothing of the potential ecological and health concerns that come along with setting off nuclear weapons, even in extremely controlled environments sealed underground.

With all this in mind, it will be very interesting to see what evidence the U.S. government provides publicly to support its claims and how these concerns about Russian activity might influence its own opinion on nuclear testing in the near term.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com