Sikorsky’s new HH-60W Combat Rescue Helicopter, or CRH, for the U.S. Air Force flew today for the first time at the company’s facility in West Palm Beach, Florida. The service hopes to put the helicopter into low-rate production this fall and move forward in replacing its fleet of aging HH-60G Pave Hawks, which has struggled to meet its operational demands in recent years.

The HH-60W’s first flight occurred on May 17, 2019, and lasted just over an hour and it included various hovering and low-speed maneuvers, according to an official press release. Lockheed Martin, who now owns Sikorsky, says that a second CRH prototype will begin flight testing next week and a total of four helicopters will be flying by the end of the summer. The Air Force, which expects to buy a total of 113 HH-60Ws, plans to make its production decision in September 2019.

“With the Combat Rescue Helicopter’s successful first flight now behind us, we look forward to completion of Sikorsky’s flight test program, operational testing and production of this aircraft to support the Air Force’s critical rescue mission,” Edward Stanhouse, the head of the Air Force’s Helicopter Program Office, said in a statement. “Increased survivability is key and we greatly anticipate the added capabilities this aircraft will provide.”

The HH-60W is derived from Sikorsky’s UH-60M Black Hawk, which is in service with the U.S. Army, among other operators. The CRH features a number of unique features, including a nose-mounted radar and sensor turret with electro-optical and infrared cameras, a new version of the AN/APR-52 radar warning receiver (RWR) system to detect incoming threats, Air Force-specific crashworthy seats for the crew and passengers, and a new long-range fuel system. The tank in the revised fuel system has roughly twice the capacity of the UH-60M.

The HH-60W will also retain various features from the latest HH-60Gs, including the same external weapons mounts on either side of the fuselage. These provide side-firing weapons at the two crew chief windows and can accept 7.62mm Miniguns or .50 caliber GAU-18/A or GAU-21/A machine guns.

The new rescue helicopters have been a long time coming. In the early 2000s, the Air Force first began actively looking for a replacement for the HH-60G as part of the Combat Search and Rescue-X (CSAR-X) program. Boeing’s HH-47, a CSAR version of the CH-47 Chinook transport helicopter, won that competition in 2006, but protests from both Sikorsky and Lockheed Martin, then separate companies, up-ended the deal.

The following year, renewed objections to a new Air Force request for proposals led to plans to replace the HH-60Gs getting put on hold entirely. In the interim, the service acquired a small number of HH-60U helicopters, another UH-60M derivative, which have become best known for supporting security and local base rescue missions at the top-secret Area 51 test facility in Nevada.

In 2012, the Air Force initiated the CRH program. After delays and threats of cancellation due to budget cuts, the service finally awarded the contract to Sikorsky for the HH-60W in 2014. Unfortunately, in the meantime, the HH-60Gs, the first of which rolled off the production lines in the 1980s, have become increasingly old and hard to maintain, despite a number of upgrade programs over the years.

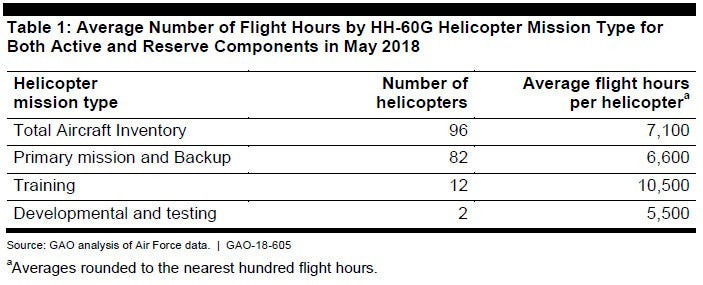

Last year, reports of growing structural fatigue and other issues across the Pave Hawk fleet began to emerge, underscoring the seriousness of the situation. At the same time, the rescue helicopters and their crews have been in especially high demand, adding to the strain on the airframes. By 2018, on average, each of the Air Force’s Pave Hawks had already logged around 7,100 flight hours, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). The type’s original service life was just 6,000 hours and some individual aircraft relegated to training duties had racked up more than 10,000 hours.

But while the Air Force sorely needs new rescue helicopters, there are still a number of potential hurdles the HH-60W will have to overcome. In its most recent annual report on the program, covering developments during the 2018 Fiscal Year, the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operation Test and Evaluation, also known as DOT&E, cited a number of potential risks.

“Qualification testing of many components of the aircraft have uncovered technical deficiencies that the Program Office is working to resolve,” the report, which came out in February 2019, explained. “As a result, the program will begin flight test and operational assessment (OA-2) with a large number of CRH-specific systems in non-operationally representative configurations.”

The systems that may not be “operationally representative” include the “tactical mission kit, Link 16 [data link], digital RWR, rescue hoist, gun mount and systems, fuel cells, armor, and primary aircrew seating.” Earlier testing showed the initial version of the new fuel cell, one of the HH-60W’s key features, was overweight and did not meet various protective and temperature requirements. “The Program Office intends to proceed with modified criteria which will allow some fuel cell leakage to be considered a pass of the specification,” according to DOT&E.

The cockpit and main cabin armor also failed certain tests, as did the aircrew seating. “Phase II qualification testing significantly damaged a production-representative live fire test aircraft structural component, the repair of which may further delay live fire fuel cell testing several months or necessitate a change in the LFT&E [Live Fire Test and Evaluation] Strategy if the article cannot be repaired,” the report added. The updated armor package is also 20 percent heavier the original design.

The added weight of both the fuel system and the armor could impact the aircraft’s performance and range, both of which are important to the combat search and rescue mission. The HH-60W press release does not mention these issues and whether they have gotten resolved or if there are plans in place already to mitigate them.

There are already questions and concerns about how well any traditional helicopter will be able to perform in a future high-end conflict in the face of ever-more-threatening integrated air defense networks, especially in the event that a stealthy aircraft gets shot down. These planes will be routinely operating in areas that are, by definition, too dangerous for non-stealthy platforms to fly.

Of course, in lower threat environments, the HH-60W will continue to be an important part of the combat search and rescue toolbox, especially with support from other aircraft to suppress and destroy enemy air defenses. The crews flying HH-60Gs now can certainly not afford to wait much longer for replacement helicopters.

Hopefully, Sikorsky and the Air Force are already well on their way to rectifying any of the CRH’s remaining issues so that the service can begin fielding the new helicopters, as planned, in 2020.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com