In the first part of our two-part series on the high-flying adventures and in-cockpit experiences of Francesco “Paco” Chierici, he talked in-depth about flying Grumman A-6 Intruders during the twilight of the type’s service. In the second part, we get into Paco’s experiences, trials, and tribulations going from a ‘mud-mover’ to a dogfighter in the legendary F-14 Tomcat. Eventually, Paco would go from a Tomcat pilot to an F-5 adversary reserve pilot tasked with teaching fleet pilots how not to die in the highly unforgiving realm of air-to-air combat. But beyond the flying, we discuss so much more, from the U.S. military’s pilot shortage to dealing with the loss of comrades to becoming a documentary filmmaker and eventually an author.

Paco’s Lions Of The Sky was recently released and he details below how the fictional story was ripped directly from the people, places, and experiences he had as a career Naval Aviator.

So strap into the cockpit, arm your ejection seat, and light the burners as we blast off on a voyage into Paco’s colorful and action-packed past.

From mud-moving to dogfighting

I had experienced Basic Fighter Maneuvers (BFM, aka dogfighting) in the training command and fancied myself a natural. As an Intruder pilot, I would try to convince as many other pilots to fly a little BFM at the end of our bombing missions as often as possible.

There is nothing quite as hideous as two Intruders trying to dogfight.

My delusion was reinforced in the Tomcat RAG (Replacement Air Group training squadron), whereas a seasoned fleet pilot I was more comfortable being aggressive than my nugget classmates, but I knew nothing about how to really fight the jet. That fact was put on display numerous times when I finally got to my first F-14 fleet squadron, VF-213 Blacklions, and had numerous flights dedicated to air-to-air maneuvering. I got my butt handed to me by some of the best Tomcat pilots on the West Coast—Slammer Richardson, Stash Fristachi, Killer Killian, Whiskey Bond, and my roommate, Waylon Jennings.

On one particularly humiliating flight from the Lincoln, a Hornet flown by Mousse savaged me on three successive engagements. But losing is the best teacher. I had come into the community with a love of aerial combat and I learned that the best dogfighters were made, not born.

I read the Topgun manual, listened in the debriefs, and eventually crafted myself into a respectable BFMer. No Pappy Boyington, but serviceable.

Of course, as good as I thought I was at the end of my Tomcat days, I was to soon find out how to really fight a plane once I became a Bandit.

Life is a series of humiliations.

The guy—or gal—in the back

The synergy between pilot and crew member was crucial to the successful employment of both the A-6 and the F-14. A good crew working well together was a thing of beauty.

Both platforms were relics of a previous age—bleeding edge when they were introduced, but hanging on at the ends of their eras when I flew them. What allowed them to compete with more modern aircraft was the proper execution of a crew concept. Of course, when the crews weren’t in sync, it was a frustrating and enormous shit show.

To help maximize the crew’s performance, both communities endeavored to pair compatible crews and have them fly together as much as possible. During the course of normal turn-around ops this was difficult to accomplish. People had different schedules and priorities which made for a catch-as-catch-can environment. But during work-ups, or combat operations, there was a much higher effort put into flying with your designated crew-member.

Working with a RIO in the Tomcat while fighting in the visual arena was totally binary. Either the pilot and the RIO bonded synergistically, fusing into a lethal team that enhanced situational awareness and weapons deployment, or they were a complete disaster.

When the pilot and the RIO weren’t well suited for the specific dynamics of the visual arena, the result was a massive net-negative. If a RIO didn’t speak enough or spoke too much, the pilot wouldn’t get enough information to properly fight the plane while assessing the threat of the adversary aircraft. When it worked, it was amazing. When it didn’t, it was frustrating and at times, embarrassing. But it was nice to always have a RIO to blame!

The Tomcat’s biggest arrow

As most Tomcat aficionados are aware, the plane was built to employ the AIM-54 Phoenix missile. Originally designed for fleet defense against large and fast Soviet bombers, the Phoenix was massive in every way, and far ahead of its time.

It weighed 1,000 pounds, was thirteen feet long, had a rocket motor burn time of over a minute, flew at Mach 5 and 80,000 feet, and delivered its 135-pound warhead to a target more than 100 miles away using its onboard radar in the end-game.

A lethal sledgehammer of a missile.

To effectively target this brute, an enormously powerful radar was required. To carry the giant radar dish and as many as six Phoenixes, Grumman designed a monster—the F-14 Tomcat—once it was clear that the F-111B failed in the role. Because the radar was so powerful and its dish so large, the AWG-9 was able to far exceed the detection, sorting, and targeting ranges of any other fighter in the world for decades.

The AWG-9’s capabilities were a generational advance over its contemporaries, the F-4 and even the F-15. Through brilliant engineering and raw power, it was able to achieve results that we now take for granted in the most modern fighters—the once upon a time groundbreaking ability to simultaneously scan, target, and fire multiple missiles.

One of my fondest memories of flying the Tomcat was the many missile shoots I was able to take part in. I shot AIM-9 Sidewinders at drones and a total of five Phoenix missiles over four separate events.

The Sidewinder came off the rails screaming like a bottle rocket, finding its way to the target in an angry corkscrew. The Phoenix was so heavy it had to be dropped from the plane like a bomb before the motor could fire. At trigger squeeze you felt the Phoenix release from the jet with a distinct thump. About a second later, which is an eternity, the motor would light off and the AIM-54 would howl past the Tomcat from below, leaving a huge plume as it rocketed into the stratosphere.

It would receive data from the Tomcat’s radar until it pitched over from 80,000 feet and closed on the target, then the RIO would cut it loose and the Phoenix’s on-board radar would consummate the deadly rendezvous.

At close range the missile would aim directly at the target, flying a horizontal path, smoking all the way to fireball. It was a sight to behold, from the shooter’s vantage point.

Despite being enormous and labor intensive to load, the Phoenix evolved with the times quite well. In most metrics, it could outperform the AIM-120 AMRAAM. The range, motor burn-time, warhead and on-board radar were no contest. The software and firmware were updated periodically allowing the missile to compete in the modern world. But like the Tomcat, it was a beast that was outperforming its design specifications a little past its shelf life.

Making the big cat dogfight

Though the Tomcat was technically a fighter plane, it wasn’t really designed for the visual BFM arena. It had a number of elements working against it when it came to dogfighting.

First was its size, it was fondly referred to as the ‘Big Fighter,’ and it was huge. One of the basic tenants of aerial combat is, ‘lose sight, lose the fight.’ Against a Tomcat that was almost impossible.

The A-model was also underpowered for maneuvering fights with an approximately 0.67:1 thrust to weight ratio. Furthermore, we had a 6.5 G limit, though there was no black box that would tell on you, so we often went well beyond 7 G. While it had massive elevators that would develop an incredible instantaneous pitch rate, the lack of ailerons and the sheer width of the plane made the roll rate sluggish.

Finally, the ergonomics of the cockpit were designed in the late ‘60s. There was no HOTAS (Hands On Throttles and Stick). The BVR intercept was run by the RIO in the back manipulating the radar and working with the pilot. Once the merge was imminent, inside 10 nautical miles, the pilot took over. But he would still have to call for the RIO to engage the dogfight mode of the radar.

Despite these massive deficiencies, the Tomcat, in the hands of a skilled pilot flying with a good RIO, could be quite lethal in the visual arena. Especially if it had the General Electric motors.

In a two-circle fight, where degrees of turn per second are a premium, the Tomcat was quite adept. But if you got the A-model slow, into the ‘black hole’ around 250 knots, you were stuck in a region the plane did not excel in. The TF-30 engines just didn’t have enough grunt to allow the plane to fly extremely slowly, nor to power back up to proper maneuvering speed.

The GE engines, on the other hand, enabled a skilled pilot to work the slow speed environment successfully. A very good pilot could even pirouette the plane using the GE engines by bringing one out of afterburner. The Tomcat would swap ends gracefully and reverse course instantly.

The auto function of the wing sweep could work against a pilot in the BFM arena as well. The angle of the sweep was a function of a variety of factors, including speed, angle of attack, and altitude.

F-15s liked to drag the Tomcat high and use their superior thrust to gain an advantage. An off-the-books tactic we used to counter this was to manually extend the wings to the fullest, then incrementally lower the flaps beyond the normal maneuver setting. It was hugely successful, but the danger was that the flap torque tubes were not designed for this and could become stuck.

Life is all about tradeoffs, and not losing to an F-15 is certainly worth the ire of the maintenance Master Chief.

I flew BFM against a variety of dissimilar aircraft as a Tomcat pilot. During a memorable week off the coast of Pakistan we flew a number of BFM and BVR sorties against the Pakistani Air Force. I still have some spectacular HUD footage from engagements against MiG-21s (J-7s).

I remember being amazed at the lack of proficiency and proper weapons employment from their F-16 pilots. When we were in the Persian Gulf, we had a week where we fought the Emirati Mirage 2000-5 pilots. They were actually quite aggressive pilots who displayed a keen awareness of the tactics to employ against the weaknesses of the F-14A. They would jam to the merge, then pull 9Gs, flying so high we almost lost sight. If we did, they would tag us with a heater (infrared short-range guided missile). But if you could survive the first merge to employ follow-on BFM, they became easy prey.

Probably the single best BFM platform I ever flew against was the F-16N. Stripped down and slicked up, it was a dogfighting monster, virtually unbeatable.

Editor’s note: Read all about the Navy’s infamous F-16N and what it was like to fly it in this past special feature of ours.

I once had a friend in a Topgun Viper park himself a couple thousand feet on my nose when I was flying a slick F-5. I counted down “3, 2, 1 Fight’s on!” and tried my damnedest to stay offensive. Inside of 270 degrees of turn, the Viper came nose on and was gunning me.

It was eye-watering performance.

Culture shock

In the summer of 1990, I had been stashed at NAS Miramar just after completing flight school. I was assigned to VFC-13, the adversary squadron, while I waited for a training slot for the A-6 at NAS Whidbey Island in Washington State. Miramar was at the peak of the post-Top Gun sugar rush. The O’Club on a Wednesday night was like what I imagine Studio 54 was like in the ‘70s. There was an hour-long line to get on base and go to the Club. It was so profitable for the base that they built a separate entrance through the perimeter fence directly into the back entrance of the Club.

Thursday mornings were hell.

NAS Whidbey Island was a markedly different cultural scene. No one drove the hour and a half from Seattle to party at the Whidbey O’Club on a Friday night. But that actually made for a very tight community. We shared the base and the Friday night happy hours with the Prowler community as well. While Whidbey didn’t have wall to wall revelers and live music, most of the aviators on base could be found at the club drinking together.

My favorite pastime was playing a dice game called Klondike. On a big night just before a few squadrons were leaving on cruise, the pot could quickly balloon to a few thousand dollars.

There was nothing like leaving for six months to make gambling with huge piles of cash seem like a good idea.

Being the FNG

I was a new guy in three different fleet squadrons and one reserve squadron. Each of these had a distinct culture which greeted the FNG (Fucking New Guy) slightly differently. My first was an Intruder squadron which I joined the day of their victorious fly-in returning from the Iraq War I in ’91. I was joining a group which had been to war together and done great deeds under tremendous stress. They hadn’t had a new pilot in a very long time and I was replacing one whom they had lost, along with his B/N during combat ops.

It wasn’t a very warm reception.

They were justifiably proud of their accomplishments and not super accepting of a bright, bushy-tailed new dude, who undoubtedly wasn’t as good as he thought he was.

It took a good six months to break into the brotherhood.

The next few squadrons I joined had a much more accepting culture. When I joined VF-213, my Tomcat squadron, it was as a fleet experienced aviator with many hundreds of hours, a few hundred carrier traps, and I was a fully qualified LSO (Landing Signal Officer). They were a very easy group to join and I felt accepted immediately.

It helped that I had a fair amount to offer, I jumped right back to LSO duties, and the Lions were eager to learn how to employ the F-14 as a ‘Bombcat.’ But despite my eagerness to be a fighter pilot, I was a complete neophyte in the world of air-to-air combat, and it was obvious. The Lions took great care training me and the other new crews and we always felt valued and encouraged, so much as these emotions are possible in a cutthroat fighter squadron.

Black cats

VF-213 almost changed their name from the Blacklions shortly after I arrived. To some, she was a cursed squadron and the black cat logo was as good a scapegoat as anything else.

The Lions had lost a number of planes due to a variety of causes in the years prior to my arrival. Tomcats hit the ramp of the ship during landing, stalled in the overhead break, exploded in mid-air for no apparent reason. There seemed to be no common thread unifying the mishaps, so straws were grasped at, including changing the famed Blacklion logo. Thankfully that wasn’t a remedy that was pursued.

When I got to 213, the mishaps continued. In fact, during my two years in Air Wing Eleven, the entire Wing lost nine jets and had six fatalities. Four of the lost planes were Tomcats and three of the deaths were in them.

It was a jumpy time.

As one of my friends, HOB Higgins, said, we felt like cats in a room full of rocking chairs. Shortly after I joined 213 we lost Kara Hultgreen while she was attempting to land on the Lincoln. I had known Kara briefly in the Training Command.

We both had Alfa Romeo convertibles and we laughed about the spotty reliability and repair costs of the Italian sports cars. She was the perfect ‘fighter-chic,’ quick with a smile, fun to be around, sharp-witted, and not afraid to stand her ground. She folded herself into the fabric of the Blacklions seamlessly and was warmly regarded as part of the ‘pride.’

The treatment she received after her death has always stayed with me as one of the greatest injustices witnessed during my naval career. Our XO replicated the mishap 100 times in the simulator and crashed 97 of them.

At the time of her death, she was a pack-player behind the boat, meaning that she was solidly in the middle of the squadron’s landing grades. Yet, as one of the first woman to fly Tomcats in the fleet, and the first to die doing so, she was held as an example of the supposed error of women in combat.

It hurt to see her sacrifice used in such a vicious manner, especially since her death had nothing to do with her gender. Kara was an inspiration for the female character of my novel, Lions of the Sky. I began with the question, “What would Kara’s journey had looked like had she lived?”

My character, Keely Silvers, is the embodiment of Kara’s fighter spirit—tough, funny, a natural pilot, and ultimately, someone to be reckoned with.

The hardest tactic to master

Death and disaster are a dark reality of military aviation. Despite all of the emphasis on safety and training rules, the environment is unforgiving and the penalty for error is swift and deadly.

I flew for 20-years and lost more than 20 friends and comrades. The list of reasons for the mishaps was dizzying: mid-air collisions, maintenance errors, G induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC), impacting the earth, and a few more.

After every mishap, we had to both grieve and disassociate ourselves. It was a battle of opposing emotional efforts. On the one hand, we would hold a memorial ceremony, complete with missing man flyby. They were all gut-wrenching affairs which forced you to confront your mortality and hold loved-ones close. Then, often hours later, it was time to get right back on the horse, back into the very same environment, the same missions, the same planes that had just taken your buddy’s life. To do that required a conscious act of delusion. Forcing fear, trepidation, uncertainty into a box and shelving them in a storage bunker deep in the back of your mind.

The pilots I knew who perished spanned the spectrum of skill level, from the best I ever saw, to some who were not very good. The Grim Reaper didn’t distinguish. We convinced ourselves that we weren’t next, that the bullet wouldn’t be in the next chamber during our aerial game of Russian Roulette.

My last two years on active duty our air wing lost nine airplanes and six people. It seemed like every two months there was an ELT sounding off alerting us to yet another mishap. I didn’t realize how much strain it put on me until I left.

After a couple of months away I slept much better and felt much lighter in spirit. But flying pointy nosed jets, pulling Gs, and burning jet fuel are as addicting as it gets. Within a few more months I was back in the air, getting my fix with the reserves, and loving every minute because I knew I wasn’t next.

Back over Iraq

My second cruise over the ‘sandbox,’ as Iraq was referred to, was enhanced by flying a different airframe in a different community. It wasn’t quite the same stuff, different day. I had a lot to learn about my new plane and a much different mission to master.

We had three basic missions flying the F-14 over Iraq during Southern Watch: reconnaissance, strike, and air superiority.

I enjoyed the variety of missions. The reconnaissance missions required flying with a TARPS (Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System), which we fondly referred to as ‘The Turd.” The pod weighed roughly two-thousand pounds and was hung towards the rear of the Tomcat. It affected the center of gravity and thus the handling characteristics of the plane. More importantly, it reduced the amount of fuel available to land aboard the ship.

I always enjoyed the added responsibility of the pressure to get good pictures and the fact that I only had one look at the boat before I was fuel critical.

One of the three cameras on the TARPS pod aimed at a forty-five-degree angle. We would frequently skirt the Iraqi border while flying along the Tigris River to obtain imagery of Iranian naval bases. Once, while flying a profile I had flown dozens of times prior, safely—if barely—in Iraqi airspace, an Iranian controller came up on the emergency frequency and warned me to leave. He followed by saying that if I did not leave, I was in danger of intercept by the Iranian air force.

Before the RIO could answer I jumped on the radio and made sure he knew we would welcome any Iranian jet that wanted to come up and play. It would have been the coolest thing in the world to do a 1v1 against an Iranian F-14.

Sadly, it was an empty threat. We did a quick lap, eagerly looking for a jet to tangle with, but no one showed up.

The strike missions we flew were similar to the missions I had flown in the Intruder. Occasionally we would plan missions against specific targets scattered across Iraq, then fly practice strikes against them as we patrolled southern Iraq below the no-fly zone. Other times we would fly to a predetermined box and check in with a ground controller for tasking. During my cruise, we never received any, we just orbited at the ready.

One of the more interesting missions we flew was to escort for the U-2s that flew parallel to the 33rd parallel that defined the southern border of the no-fly zone. Iraqi jets were permitted to operate between the 32nd and 33rd parallels in a narrow band of air space. The rules of engagement prevented us from engaging with the Iraqis so long as they stayed in their box, but if a MiG penetrated south of the 33rd, then it was fair game—the rules allowed us to chase it down.

The Iraqis often played a game of chicken, flying their MiG-25s south at high speed then turning them away at the last moment, avoiding triggering the line of death. The AWACS would alert us of the threat and we would commit toward the target, arming up the missiles in case shit got real. While it never happened to me, it was always cause to spike the adrenaline system and ultimately a whole lot more fun than burning another hole in the sky.

When we took on the tasking to escort the U-2s however, the threat became much more real. The U-2 flies at extremely high altitude, though well within missile range of the AA-6 air-to-air missiles the super-fast MiG-25 Foxbats carried.

We took the threat to the vulnerable U-2s very seriously and took it upon ourselves to devise a plan that would allow us to protect the pilots from an Iraqi jet that wanted to take a shot. The challenge was that the U-2 flew far higher and much slower than the Tomcats. One of our RIOs, Smash Kormash, devised a zig-zag flight path where we could fly below the U-2s while maintaining our slowest tactical speed.

While they flew their missions oblivious to us, we were flying a long, jinking pattern below, keeping our knots up in the event a Foxbat showed any interest.

RIMPAC

Rim Of The Pacific (RIMPAC) ’96 was my last at sea period with the Tomcat, VF-213, and Air Wing Eleven. It was a bittersweet three-month mini-deployment for me. I felt at the top of my game, yet I was just a few months from leaving active duty for whatever lay beyond.

As an Air Wing, the involvement of the dozen or so foreign ships was largely transparent to our operations. The only time we noticed anything unusual was on the occasion when our practice intercepts were controlled by someone with an Australian, or Spanish, or Japanese accent. There were no foreign navy air assets that we wrangled with, so the international aspect of the exercise was no factor for the aviators.

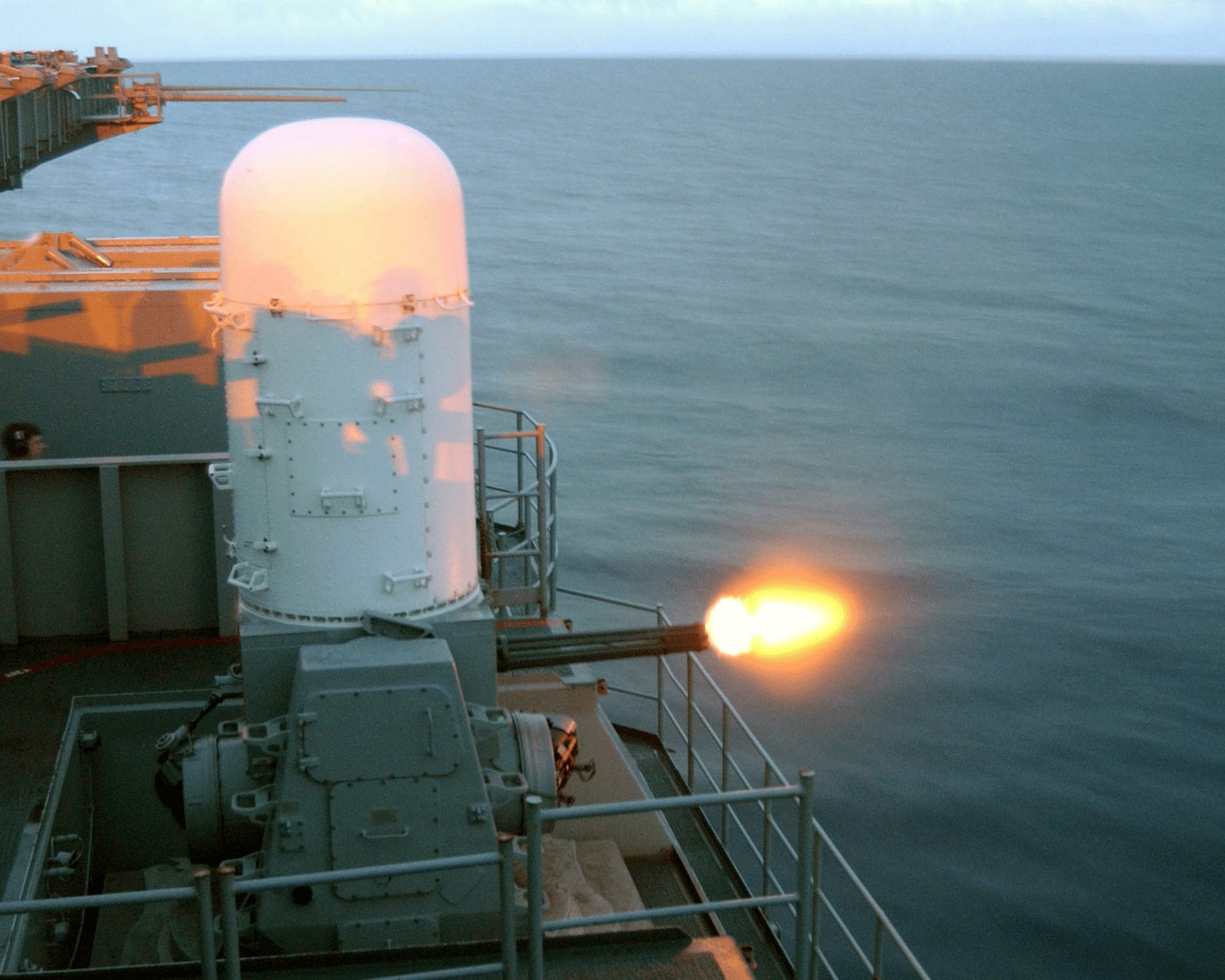

All of that changed on the night of June 3rd. The USS Independence was operating in RIMPAC along with the USS Kitty Hawk, which Air Wing Eleven had transitioned to. One of the A-6s from VA-115, attached to Air Wing Five, was towing a target on an extremely long cable. The target was to be fired upon by a Japanese destroyer, the JDS Yuugiri, with her Mk15 Phalanx 20mm CIWS.

As the Intruder flew past, the Yuugiri armed her gun far too soon. The CIWS performed as advertised, immediately shooting the A-6 out of the sky. Fortunately, both crew members ejected safely, though they never quite lived down being the first US plane shot down by the Japanese since World War II.

Grumman reliability through raw dedication

I was lucky in that I caught both the A-6 and the F-14 during good cycles of their maintenance and reliability. Ironically, I believe it was due to the fact that they were both near the ends of their service lives.

As I mentioned earlier, shortly after I checked into VA-155 as an A-6 Intruder pilot, we began receiving brand new jets with as little as ten hours on the airframes. The old jets they were replacing had been depressing to fly. Wing crack issues kept us to below 4 Gs, which sucked badly.

Having a brief taste of a jet that was barely hanging on gave us an appreciation for the new Intruders we received. We flew the hell out of them, though, knowing the squadron was to be decommissioned when we returned from cruise.

I had much the same experience when I was in VF-213. The squadron had experienced so many bizarre mishaps over its recent past that we got the best of everything. The best A models (a dubious claim), the best maintainers, an amazing maintenance Master Chief (Hulbert), and priority for parts. The maintainers were determined not to be a factor in any future mishaps and the jets were groomed to perfection.

On my last cruise I was the Avionics and Armament Division Officer, responsible for the majority of the maintainers. It was a great opportunity to observe them as they worked the jets and I could not have been more impressed. Unbelievable intelligent and hardworking young men and women working twelve-hour shifts in the blazing heat and stifling humidity of the Persian Gulf. Not once during that deployment did I miss a sortie, which is unheard of. There was a launch where I came close, however.

I had a Central Air Data Computer (CADC) issue that we discovered just after engine start. The CADC was vital to making the complex wing sweep mechanism work in the Tomcat. It was a hundred-pound box just behind the cockpit under a panel with dozens of fasteners. It wasn’t a difficult fix to swap it out, but it took time and effort.

When the mechanic informed me of the problem, I knew I was going to miss the launch. We only had ten minutes. But he said, “Don’t worry, sir. I’ll get you going. Hang tight.”

I watched as he pulled the massive box and scrambled down my ladder, hustling across the flight deck in 130-degree midday heat. I knew he had to lug that box down three flights of ladders to his shop, grab a new one and lug it back up.

With minutes to spare before the Air Boss canceled me, I saw him labor back across the deck, up my ladder, and onto the back of the jet. The box was inserted and checked, the panel was refastened, and we were ready to go with barely a moment to spare.

I was deeply moved by that commitment, then, and now. It was an impressive display of dedication and professionalism and I have never forgotten it.

Qualifying Carriers

I had the great privilege to deploy on the Forrestal

class

USS Ranger (CV-61), the nuclear-powered Nimitz class USS Lincoln (CVN-72), and the first-in-class USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63), getting over 100 traps aboard each. They all hold a special place in my memory and were distinctive in surprising ways.

I am glad I served aboard the Ranger first, as she was the smallest and oldest. Despite her age, and the fact that I was on her for her very last cruise, she was a very well-maintained ship. I remember distinctly that Ranger and Air Wing Two were a fantastic pairing. You could set your watch by the sound of the first catapult shot of a scheduled launch. It was the kind of precision the ship’s company took great pride in and it was reflected in every aspect.

The dirty-shirt wardroom, where the aviators ate, was arranged differently than other carriers. It was a subtle, but significant variation in that the tables were only 4-tops, like in most restaurants. Other carriers had massive picnic-style tables that could seat 20 or more.

Squadrons would have tablecloths made with their logos, staking out territory. This tended to divide the wardroom, where aviators felt compelled to eat at their squadron table even if they were alone. On Ranger you generally ate with whomever you were in line with, regardless of squadron. The result was a much tighter Air Wing where all the aviators knew each other, reducing parochialism and enhancing camaraderie.

The best part about cruising on Ranger’s last cruise was being able to modify the living quarters with impunity. We knew the ship was to be decommissioned right when we returned. That gave us a sense of liberty when it came to some major modifications which weren’t possible on a ship that would be carefully scrutinized during a turnaround period.

One threesome of Lieutenant Commanders took possession of a 6-man bunk room. They saved half of the bunks, desks, and wardrobes, then cleaned out the other half, chucking it all overboard one night. It left a huge empty space, which was an unknown luxury on a warship.

Despite the fact that a carrier is an enormous 1,100-foot long ship, it is illusory when it comes to space inside. 5,000 people are crammed into that tiny real estate and there is no room at all for comfort or lounging—except for in this one room on Ranger.

The guys filled that empty space with carpeting, a poker table, couches and lounge chairs, an awesome poker lamp, and they finished it up by covering the drab gray walls with fake wood tack paper. It was an incredible space to congregate, drink some illicit beverages, and play poker deep into the night.

The downside of the Ranger was that she was a conventionally powered ship. That meant that she didn’t have unlimited fresh water for ‘Hollywood’ (long) showers or air conditioning.

The Lincoln, my second home away from home, is the only ship I served on still in service. As a nuke, she was able to pump frigid air into all the spaces even in the miserable heat of the Persian Gulf. You may laugh, but that was a major enhancement to the quality of life. She was also able to make unlimited fresh water. Despite that, she had the same spring-loaded hand-held shower nozzles as all the conventional boats. We easily bypassed that restriction with a three-inch C-clamp, which we would affix to the shower head to hold down that damn button. With that minor mod, we were able to enjoy an almost normal shower after coming back from a six-hour mission over Iraq—a luxury we thought we absolutely deserved.

The Kitty Hawk was the ship I spent the least amount of time aboard, just half a work-up and a RIMPAC. I don’t remember too much about her other that she was definitely my least favorite. She wasn’t as clean or well run as Ranger and she wasn’t shiny and new as Lincoln. We took to calling her ‘Shitty Kitty,’ probably because we were a little bitter about the crap air conditioning again.

It doesn’t take much to make an aviator bitch.

Sainthood

Once I left active duty, I joined the airlines as a commercial pilot. It was a good decision for family reasons, but after a few months, I found myself missing the smell of jet exhaust and the sensation of pulling Gs.

I was extremely lucky in that a good friend of mine from 213 had joined VFC-13 at NAS Fallon as an active duty pilot. He called me and told me they were forming a selection board to screen for new reserve pilots.

I couldn’t put my package together fast enough.

I was selected and began flying a few months later and I couldn’t have been happier. Flying pointy nosed, afterburning fighters was still in my blood and I was thrilled to get some more hits at the JP-5 crack pipe.

The Adversary syllabus at the Saints (VFC-13) was extremely rigorous. As I mentioned earlier, when I left the F-14 I felt I was a pretty good fighter pilot. Once I began the syllabus with the Saints, I quickly learned I was still a neophyte.

These guys were amazing pilots who were also able to recall each instance of each engagement. It was mind-blowing. Despite having only 15 hops, the syllabus took anywhere from nine months to a year to complete. The standard was perfection and the norm was multiple re-flys. I was so happy to finally complete the training and join the squadron as a basic adversary pilot.

Despite the fact I was flying pointy nosed jets and wearing a flight suit, it was obvious we weren’t an active duty squadron. About a third of the pilots were still on active duty, assigned to the Saints for administration and continuity. A few more were full-time reservists, called Selective Reservists. The rest of us were airline pilots who came in seven to ten days a month.

The core of the unit stayed together for the whole ten years I was there, which made for a very tightly knit group. But we spent most of the time scattered across the country living with our families and working our real jobs. In a fleet squadron, it was the opposite, you spent the vast majority of your time with your squadron mates and at work, they were your de facto family. Your spouse and kids got what was left over on the occasion you were at home.

I left active duty for family reasons and I’m glad I did. But the closeness of a fleet squadron is something I’ll remember fondly as long as I live.

From Tomcats to Tigers

There were some major aspects of moving to the F-5 from the mighty Tomcat. The most obvious were size and a single-seat cockpit. The Tomcat usually took to the sky at around 65,000 pounds. It was 63 feet long and 64 feet wide. The F-5 weighed around 15,000 pounds in the max configuration we flew her in, with a single centerline drop tank—less than the Tomcat’s fuel load alone. The Tiger was 47 feet long and 26 wide—a lawn dart compared to the Big Fighter.

The Tomcat pilot famously had a RIO for the pilot to blame for all his errors, while in the F-5 you had to rely on a bad wingman to suck up the critique. The cockpit in the Tomcat was huge, lots of room for limbs and noggin. Strapping into the F-5 was akin to putting on your last piece of flight gear.

It became a part of you.

It was so tight in that cockpit that I couldn’t straighten out my legs or sit completely straight. If I had been forced to eject, I’m sure I would have suffered some negative consequences.

The Tomcat was so fun to fly, it was like a muscle car, a ’65 Shelby Cobra. Lots of power, even in the A model, a sense of weight behind the controls, it buffeted under G, bucking and straining through the turns. The F-5 was like a go-kart. Underpowered but light in the controls and nimble as all hell. It could do two aileron rolls per second.

The Tomcat was a fleet bird, built to carry missiles and bombs into combat. She had so much drag that when you were supersonic and came out of burner it felt as though you were slamming on the brakes. The Tiger was clean, just an AIM-9 and a telemetry pod on the wingtips, and occasionally a centerline fuel tank. She slipped through the ‘number’ (Mach 1) easily.

They were both jets from the same era, but the Tomcat was a warfighter, bristling with equipment meant to find and destroy the enemy and survive the encounter. Radar, RWR gear, chaff and flares, IFF, TCS, and much more. The aviators had to be proficient with all of the equipment, using as many as possible on each mission. The F-5 was a pair of engines and wings. It was so simple and it was perfect for reservists.

All we had to do after a few weeks away was come back for one warm-up flight and we were ready to rock. The F-5Ns the squadron received from the Swiss starting in 2005 were a bit more complex, sporting anti-skid brakes, basic pulse radar, RWR gear, and an INS (inertial navigation system). But it was an incremental upgrade, still basic when compared to the fleet birds.

It was a pleasure to jump into the F-5 and go fight, whether it was the professional adversary mission we provided to the fleet, or the in-house 1v1s we loved more than anything. But it could never match the adrenaline rush of flying the Big Fighter from the boat. Each and every launch was like suiting up for the ‘Big Game.’

Tiger trick

Air-to-air fighting doesn’t require crazy maneuvering. It isn’t about who can do the wildest stunt to gain an advantage or who has a secret trick up his sleeve only pulled out when needed to get that last-ditch advantage. Real dogfighting isn’t like in the movie Top Gun—hitting the brakes and he’ll fly right by. The best fighter pilots are masters of their plane. It is an extension of their bodies and minds. They are able to fly it to the absolute edge of performance, whether that is a rating high G two-circle fight, or a one-circle fight where nose position is key—as well as myriad permutations and variations in between, such as rolling and flat scissors.

It is as much an intellectual challenge as a physical one, where creativity meshes with integrally with skill. The best pilots I saw were able to think three merges ahead and set up their opponent for the weapon of their choice. It was a thrill to experience, even from the wrong end of the kill shot.

That said, there were some fighter pilots who were just a whole level above the rest in their stick and rudder skills. One of the best at a specific ‘move’ was a friend and squadron mate in VFC-13.

Memo could swap ends in an F-5 more perfectly than I believed possible. Somehow, when he was defensive in the vertical, he was able to pirouette the Tiger in a manner that reversed his course and still afforded him airspeed to continue maneuvering. I witnessed it many times while nipping at his heels over the Nevada skies. Sure, I was just moments away from a guns kill, then he would snap the jet impossible fast and pass me close aboard going the opposite direction.

He tried in vain to teach it to me. I could come close. I could swap direction and end up slow, or I could mush through a turn and keep some knots on the jet, but I could never get the right combination of both.

It still pisses me off.

Editor’s note: You can read more about what it is like putting the F-5 to work as an adversary in this past special feature of ours.

Forever F-5

The F-5 has lived many lives and is on the verge of yet another. It began in the ‘60s as a basic fighter/bomber we could sell to allies who couldn’t afford top of the line fighters. It excelled at that mission. It has been continuously updated to meet the requirements of the evolving battlespace.

Aerodynamically, the F-5 will always be what we call a category 3 fighter, where the F-35 and F-22 are now category 5 fighters. Compared to modern jets, it is underpowered, slow, and bleeds airspeed badly in a sustained turn, not to mention it has no stealth other than its tiny size. But with just a few modifications, the F-5 is being turned into a threat plane with a legitimate sting. The newest upgrades include an AESA radar, good RWR gear, chaff and flares, a jamming pod, and a helmet mounted cueing system for a high off-boresight IR (infrared-guided) missiles.

A Tiger so outfitted can provide Super Hornets and F-35s a legitimate threat, especially in the training environment.

One of the aspects of the Tiger as an adversary platform that has served it well across the decades is that if you are a Blue fighter and you lose to an F-5, there is a definite error you made. A decisive training moment that can be isolated and debriefed and remembered, so that the same mistake will not be made in combat.

It’s your captain speaking…

Stepping into the cockpit of a 737 after flying F-14s and F-5s is like stepping into a different skin. The person and the mindset you have as a fighter pilot and the manner in which you fly the plane are diametrically opposed to the style of piloting required to be a good airline pilot.

A good flight in a fighter involved lots of sweating and action, high Gs, close passes against another plane with a thousand knots of closure and aggressive, in-close maneuvering. A good flight in an airliner in one where the passengers feel as if they are enjoying a nice cocktail in their living room and just happen to be whizzing across the continent at 500 knots. Maybe a movie and a nap—certainly nothing exciting.

And that’s ok. That’s the way it should be. That is why I fly Yak-50s on the weekend while some of my friends are on the golf course. I still get to go up and pull Gs and dogfight against other fiends, but now it’s in propeller planes and we have to pay for our own gas!

Socially, in the cockpit, the worst kind of airline pilot to fly with is the former military jet jock who tries to hang on to the glory of his former life. We get fantastic training from our company on how they want us to fly the airliners, there’s no need to bring up war stories from your fighter days.

All the pilots in an airliner cockpit here in the U.S. are exceptionally qualified to fly commercial planes, whether we came up flying canceled checks in a Cessna 172 in the middle of the night or were blasted from an aircraft carrier in the Persian Gulf.

Where have all the pilot’s gone?

It has always amazed me how poorly the Navy treated its aviators. Even during the best of times, we had to battle the establishment to maintain our distinct identity and esprit de corps. The relentless tide of bullshit that the administrators threw at us demanded a constant self-evaluation—do I really love flying these jets so much that I’m going to put up with this crap?

The stark reality is that a carrier costs $12 billion. Add a few billion more for the requisite ships and now you’ve got a Carrier Strike Group, the basic war-fighting unit of the modern Navy. Add a few billion more and you can arm that strike group with purpose, the seventy-odd planes and helicopters required to outfit the Air Wing that embarks on the carrier.

The many billions in ships and aircraft exist for one purpose, to project power against the enemy from nearly any place in the world. The 11 (counting the impending arrival of the Ford) carriers and their associated Strike Groups are the most lethal offensive weapon the world has ever seen. Yet they exist almost entirely for the deployment of the 150 or so aviators that will fly the jets and helicopters into harm’s way.

Recent studies have determined that it costs $6-11 million and five years to fully train a front-line combat aviator. In any other environment in the world, the asset that provided the highest value and costs the most to replace would be considered a prime asset. But in the US military, combat pilots are treated like crap and subjected to harassment from senior ranking support personnel.

The misalignment of interests is grating during the best of times, but when the airlines begin to hire after many years of drought, the frustration finds a ready expression in the form of an exodus.

In the last five years the Navy and Air Force have lost billions in highly trained aviators to a profession they are severely overqualified for because they couldn’t take the bullshit anymore. Most of us would have continued in the military for a fraction of our airline salaries if only they hadn’t squeezed the fun from the most fun job you could ever have.

The resulting pilot shortage in the military is no shock to those of us who served. But it has helped to create a new, unforeseen industry—contract adversaries.

Back in my day, when you needed someone to play the red fighter—the bad guy—you simply scheduled an in-house asset to that role. So, an F-14 squadron scheduling a 2v2 sortie would need four Tomcats. We thought nothing of it as the planes, parts, aviators, flight hours, and fuel were plentiful. Today none of those parameters are true.

Now factor in that the dramatically improved capabilities of fifth-generation fighters mean fewer planes are required, and thus fewer planes are on the flight line, and now you have a training issue. Fast forward a few years and we now have at least four major players in the contract adversary space. They have a corral full of former fighter pilots, frustrated airline pilots, who are happy to fly pointy-nosed crack pipes for relatively low salaries.

There is a glut of third generation fighters on the world market – Mirage F-1s, F-5s, A-4s – that are being upgraded with AESA radars, top line RWR gear, jamming pods, and other fifth generation toys, making them capable adversaries to F-35s and F-22s and a fraction of the hull costs. The Department of Defense is thrilled it doesn’t have to pay for any of the assets or personnel, they merely manage the requirements and demand high standards.

The contract adversaries are staffed with former Topgun and Weapons School graduates, men and women who have been trained to the highest standards and represent a tremendous vault of corporate knowledge. They are eager to provide the mission they trained for while escaping the grinding mundanity and incompetence of military leadership.

Contract adversaries are here to stay and I believe they will be an excellent solution to the problems the modern military brings to readiness.

Speed And Angels

I never took any moment of flying in the navy for granted. It always seemed like a spectacular playground filled with action and adrenaline. When I was in the reserves, I wanted to tell the real story of naval aviation. I decided a documentary would be the best way to make that happen.

I convinced a good director friend of mine, Payton Wilson, to come to Fallon with me for a weekend with her camera. At first, she was reluctant, she was a female filmmaker from San Francisco, just about the opposite demographic that would be interested in making a film about Navy pilots. But once I got Peyton in the ready room and on the flight line, she began to come around.

The energy of a squadron is infectious. The personalities and banter are unique. And the type of flying we do in the Navy is both visually beautiful and dramatic. Within a few weeks, we had made the fantastic sizzle reel called Last of the Dogfighters and I used that to both get permission from the Navy to produce the full-length documentary and raise the funds needed to pay for the film.

We originally intended to make a film about the Saints and dogfighting, but once Peyton met the RAG students we were fighting, she fell in love with their stories.

The RAG students were going through an intense year of change. Every day they faced a new and exciting challenge and an opportunity to fail. Every couple of weeks there was a new final exam they had to prepare for, and of course, the huge culminating obstacle of carrier qualifications made for fantastic, foreboding drama.

Once Peyton convinced me that the Saints weren’t cool enough for our own full-length movie, we quickly settled on the two pilots we would follow for the course of the film, Jay and Meagan. They both had amazing backstories, incredible obstacles they were forced to overcome just to get to flight school. They are both compelling, charismatic personalities who light up the screen. And they both continued to give to their stories in ways we could not have anticipated before we began following them.

They each had ridiculously dramatic events once they left the RAG that we discovered by accident. If it had been scripted, it would have defied credulity, but in real life, both stories were remarkable and showed just how amazing Jay and Meagan truly are.

Easily the most difficult part of making Speed And Angels was the air-to-air filming. It literally took me years to finally get permission to fly F-5s and F-14s on dedicated filming sorties. The budget for the cameras, film crews, camera Learjet, and the bill from the government for the Tomcat and Tiger time was nearly half of the total budget of the film. But it’s a movie about beautiful jets so we did everything in our power to get beautiful footage.

To tell the story of a dogfight is a difficult cinematic challenge. Actual aerial encounters take place at 20,000 feet, hundreds of knots, and after the planes merge, they can be a mile or two from each other as they claw through their high G turns to point back towards each other again. I had to choreograph a series on maneuvers and shots we could film and then cut together to give the viewer a sense they were in the cockpit, with their hands on the controls, pulling for a shot.

We filmed from the air, from a specially modified Learjet, and from a mountain top in Fallon— Fairview Peak. We strapped small cameras throughout the cockpits of the fighters to give a number of vantage points, including on the helmets of some of the pilots as they were maneuvering or landing on the ship.

All in all, it was an amazing experience. We set out intending to make a cool film about the Saints and dogfighting over a year and ended up making an amazing movie about two of the last F-14 students struggling against every obstacle imaginable to achieve their dreams and much more.

Lions Of The Sky

I was a fighter pilot for 20 years, but I’ve been a writer all my life. Writing novels has always been my dream, aside from flying fighters. I finally got the gumption to combine my two passions into a great story.

On a macro scale, Lions Of The Sky is a fictionalized distillation of the crazy stories and characters I experienced over two decades in the Navy. Nearly every insane scene, both in the cockpits, in the ready rooms, and in the Officer’s Club, actually happened, with a little extra fiction dust thrown on top. That includes the dramatic, climactic final battle scene between the United States and China in the South China Sea.

Not to give away too much, but in the mid-‘90s a U.S. Navy plane thought it was chasing a U.S. submarine for training. It turns out the sub was really Chinese and its captain thought he was being attacked. He radioed back to the homeland and a wave of Chinese fighters were launched. The carrier launched its own fighters to meet the challenge. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and the situation was quickly diffused. But in my book, things get a lot more interesting.

More specifically, my novel is about a hard-boiled RAG instructor, Slammer Richardson, who became somewhat of a legend, but at the cost of losing his best friend. He is eager to get back to the action of the fleet because he can see that something big is brewing in the South China Sea. He’s got some misgivings about women in the cockpit so he does his best to avoid them, but the last class he’s assigned to mentor has not one, but two female students.

Being aspiring fighter pilots, the women are bold and brash, and have no intention of fading into the background. The challenges of training in the F/A-18 force them to choose wildly different paths as they navigate the many hurdles and force Slammer to come to terms with thoughts he’d rather leave deeply buried.

One of the aspects of flying in the Navy that always fascinated me was that once aircrew finish the RAG they are qualified to go to the fleet and possibly into combat, though they are far from proficient. It has happened many times and to Jay in Speed and Angels, in fact.

During the course of the training in the story, there is a constant background drumbeat of aggressive action by China against their opponents to territorial claims in the South China Sea. The tension rises steadily as the students face successive challenges. Ultimately, Slammer and a few of the students that survive the RAG are assigned to the carrier that is sent to face the Chinese.

Far before the new fleet pilots are ready, they are thrown into a situation where the opponents are legitimate, the missiles are real and life and death decisions are made at the speed of sound.

Much like Speed And Angels, I wanted Lions Of The Sky to be about the people behind the larger story. And also, like the film, as much as possible, I wanted the readers to feel like they were a part of the action, not just observers.

Lions is a fantastic novel of action and peril, about the intense and real personal stories that underlay the wider fabric of geopolitical conflicts.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…

Easily the worst experience I ever had in a Navy jet was the day I crashed an F-5. It’s a long story, but the salient points are that I had blown tires on landing and skidded down the runway on nothing but the metal hubs. As I left the end of the runway, I shut down the engines just before the plane flipped over, shattering the canopy. The plexiglass broke into razor-sharp shards and as the canopy rail bent back one of the shards pierced my neck like a dagger, just above the jugular. If I had been going a knot or two faster when the plane flipped I would surely have bled to death.

The second worst day I had in a Navy jet was my last flight. It was the culmination of over two decades of effort, sweat, dodging death, joy, and epic fun. But I had reached the end of my tenure and the next step for me in the military would have been a desk.

I had spent a solid 20 years in the cockpit and I wasn’t ready to leave yet, but that wasn’t my decision. I felt like a perfectly healthy person who had to walk into the hospital to have his legs amputated. It didn’t make sense to me. But such is life.

I had so many fantastic experiences in the Navy and in the cockpit. loved flying low-levels through the Cascade mountains during beautiful summer days, weaving back and forth with the other jet across valleys and darting through canyons, showing off to the people out boating or hiking. Bringing the Tomcat in for a 600-knot shit hot Break at the ship and nailing the landing was as intense as it gets.

But if I was given the opportunity to go back and relive just one experience from my 20-year thrill show, I would have to drop back into December 1999. I was flying F-5s as a reservist, but I was also a junior airline pilot. I didn’t want to work over the Millennium New Year as I surely would. So, I got the squadron to cut me orders to fly with the reserves from December 15th of 1999, to January 7th of 2000.

We didn’t have any ‘customers’ and there were few pilots in the squadron, so there were plenty of jets to play with. For three weeks, minus Christmas and the big New Year’s blowout in Tahoe, I flew three air combat sorties per day against the best dogfighters in the world. The weather was perfect, the gas was free, the jets were plentiful, and the dogfighting was the most intense and fun I ever experienced.

If I make it to Heaven, that’s what every holiday season will be like.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com