Congress has demanded that the Pentagon conduct a detailed assessment of the U.S. Marine Corps’ troubled CH-53K King Stallion program and examine potential alternatives, such as the CH-47 Chinook. Any decision to cut back CH-53K purchases, or abandon them altogether, would be a major blow to the manufacturer Sikorsky, now a part of Lockheed Martin, as well as a boon to Boeing, which makes the Chinook. Changes in the King Stallion program could also further delay Marines from getting a critically needed replacement for their aging CH-53E Super Stallions.

Bloomberg

was first to report the existence of the Congressionally mandated assessment of alternatives on May 6, 2019. Senator James Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican who presently chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee, requested the review on Apr. 4, 2019. It’s not clear when the review formally began.

But at the time of Inhofe’s request, legislators were considering whether to approve a request from the Navy, which manages the CH-53K program on the Marine Corps’ behalf, to shift additional funds into that program to support continued work on fixing various technical problems that have emerged during the King Stallion’s flight testing. On Apr. 19, 2019, Congress approved the request to move an additional $79 million from other accounts into the CH-53K program, around half of what the Navy requested. It is unclear whether or not this was tied to the Pentagon acquiescing to Inhofe’s request for a review.

The Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) is leading the process, which will examine the “cost, schedule, and performance” of the CH-53K program, as well as provide “an assessment of alternatives for other platforms that might meet the mission,” CAPE director Robert Daigle told Bloomberg in an interview. Daigle is set to step down from his post this month and plans to return to the private sector.

“We have a limited amount of time to try and inform that decision as much as possible – so we have a very short window in which to do the best job we can on this analysis,” Daigle said to Bloomberg, though it was unclear if this was driven by his own limited time remaining on the job. At the time of the interview, the CAPE director hoped to have the assessment complete in “a handful of weeks.”

Whatever CAPE’s findings are, they will have a major impact on the CH-53K, which has been in protracted development since 2006. By 2014, the date the Marines expected to reach initial operational capability with their new King Stallions had slipped from 2015 to 2019. An annual report that the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation released in February 2019 showed this had slipped again, but did not offer an updated timeline.

“The Program Office is working a major schedule revision,” that report explained. There is a “need to correct multiple design deficiencies discovered during early testing. These include: airspeed indication anomalies, low reliability of main rotor gearbox, hot gas impingement on aircraft structures, tail boom and tail rotor structural problems, overheating of main rotor dampers, fuel system anomalies, high temperatures in the #2 engine bay, and hot gas ingestion by the #2 engine, which could reduce available power.”

Reports of these problems, which you can read about in more detail here, had first emerged publicly in January 2019. Continued gearbox trouble has proven to be especially vexing, being a major factor in earlier delays. In 2016, the Navy insisted the issues had gotten resolved, only to see subsequent flight testing contradict that assessment. The Pentagon’s latest Selected Acquisition report to Congress, which Bloomberg

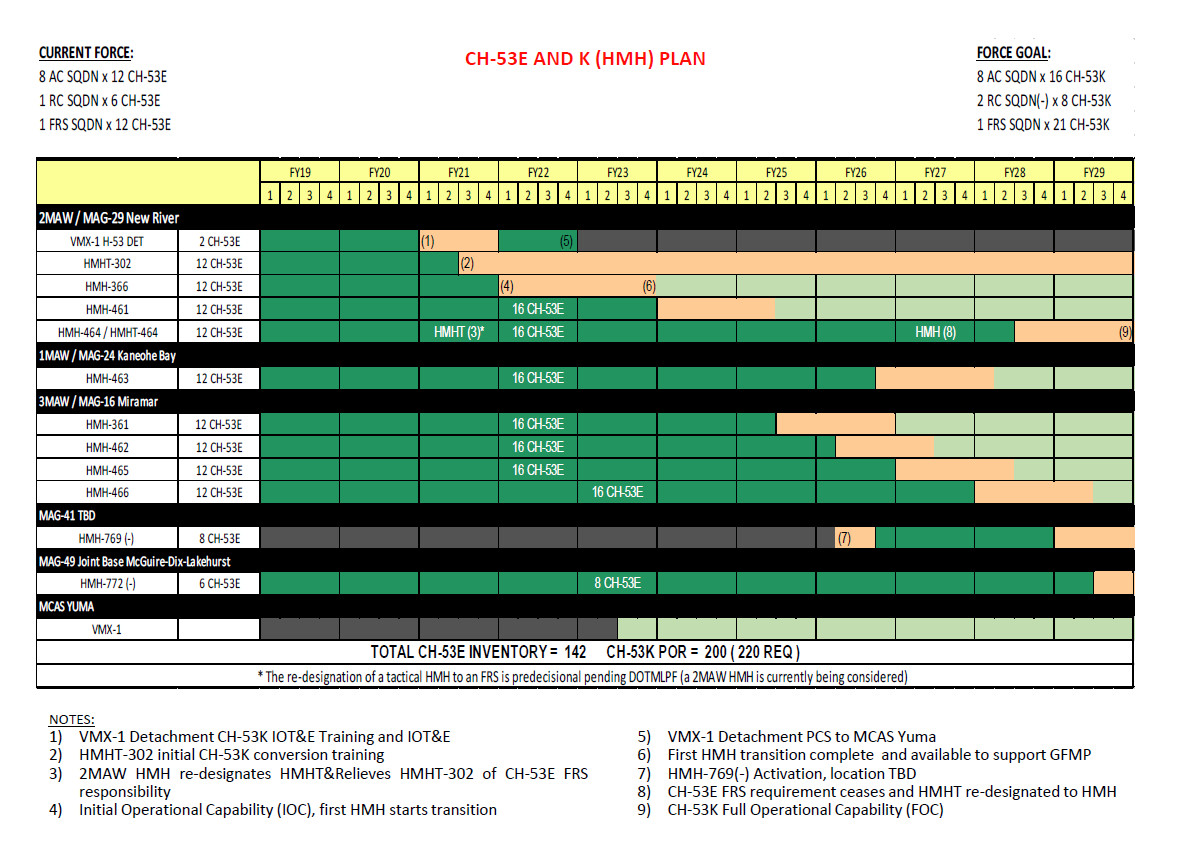

had also obtained earlier in 2019, said the CH-53K still had a total of 126 technical deficiencies that needed correcting. The Marine Corps’ 2019 Aviation Plan now says the CH-53K IOC date is the beginning of the 2022 Fiscal Year, which starts on Oct. 1, 2021.

All of this has driven up the estimated unit costs of the King Stallions, which stood at around a whopping $122 million, roughly the same as an F-35B Joint Strike Fighter, as of 2018. The Marines and Sikorsky have said that this could drop to an average of around $80 million if the Corps purchases its planned full fleet of 200 of the helicopters. The first production contract is under negotiation right now, despite the parallel Pentagon review. The Marines already have seven pre-production examples, having taken delivery of the first one in May 2018.

“I would expect that [deal] in the next coming weeks,” James Geurts, the Navy’s top acquisition officer, told the Senate Armed Services seapower subcommittee on Apr. 10, 2019, making no mention of any CAPE assessment. “There are some things need to be fixed and I want them fixed in the production aircraft when they roll off.”

But there is some indication that the review might have factored into the hearing. Senator Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, raised the possibility of the Marines buying an alternative helicopter instead, adding that he had spoken to Marine Corps Commandant General Robert Neller about the King Stallion and that the top Marine officer was less than pleased about the situation.

“To be honest with you, I was disturbed by General Neller’s comments. He expressed pretty significant frustration to me about the status of this program,” Hawley said. “Do its [the CH-53K’s] capabilities justify its premium price over, say, the CH-47?”

CAPE’s Robert Daigle only mentioned the Chinook by name as being among the alternatives to the King Stallion that his office was considering. It is the only other American-made heavy lift helicopter currently in production.

At least publicly, it is the position of the Marines, and not surprisingly Sikorsky, that only the CH-53K can meet the service’s requirements. These include the need for the helicopter to be able to carry a total payload of up to 36,000 pounds, including items carried slung below, and be able to carry 27,000 pounds out to an operational radius of 100 miles specifically for ship-to-shore missions during amphibious operations. The latest CH-47F model can carry around 21,000 pounds of cargo.

There are also concerns about the extent of the modifications the Chinooks would need to operate in a maritime role on a protracted basis. While U.S. Army Chinooks, as well as special operations MH-47s from the elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, do occasionally operate from ships, and examples around the world do so as well, it is typically for relatively short duration missions.

These changes, among other things, would include features to help mitigate the impact of saltwater corrosion that shipboard aircraft encounter. In an example of how serious the issue would be, Army CH-47s conducting land-based relief efforts in the United States along the Gulf of Mexico in the aftermath of Hurricane Michael in October 2018 needed regular washdowns to prevent dangerous salt buildup just from flying along the coastline.

There’s also just the question about whether the facilities on board existing Navy amphibious ships would have the necessary space and features to support the CH-47 and its maintenance needs or if those vessels hangars and aircraft elevators would even be able to physically accommodate the Chinooks. Those same physical constraints could be a factor in what parts of an amphibious ship’s deck the helicopters can use for takeoffs, landings, and the loading and unloading of cargo, all of which could have an impact on sortie generation during actual operations.

The CH-53K’s maximum height is close to 28 feet, but that’s predominantly due to the tail and tail rotor, which can fold down and to the side. This significantly reduces the overall height, as well as overall length, for parking the helicopters on an amphibious ship’s flight deck or hangar down below.

So, while the Chinook’s maximum height of 18 feet and length of 98 feet make it dimensionally smaller than the “unfolded” CH-53K, it has no way to readily make itself more compact for shipboard operations like the King Stallion. The CH-47’s dual rotors also present different safety requirements for how far away it needs to be during operation from other aircraft and potential hazards, which could be an issue for routine operations from an amphibious ship.

By CAPE’s Daigle’s own assessment, the Chinook would not be able to offer a one-for-one replacement for the CH-53K just in terms of performance. “The analysis we’ve have done so far doesn’t suggest that the ’47 is actually going to meet the lift that the ’53K will provide so if you were going to go down the ’47 route, our current estimate says there will be an operational impact,” he told Bloomberg.

This initial assessment was based, at least in part on information that Boeing submitted on a marinized CH-47 concept to CAPE and a meeting between the two parties at plane maker’s helicopter plant in Philadelphia on Apr. 25, 2019, according to Bloomberg. Still, Boeing would have to be eager to at least present as viable an alternative as possible.

The Army, its largest single CH-47 customer, has proposed abandoning a purchase order of 28 additional F models in favor of reallocating those funds, approximately $962 million, elsewhere. This proposal has left the future of the Army’s CH-47F program in limbo, though there is growing Congressional pushback to the plan. Even just securing a portion of the orders that might otherwise go to Sikorsky for CH-53Ks could help ensure the stability of the Chinook line.

Unfortunately, whatever option Congress, the Pentagon, the Navy, and Marines agree to in the end is still likely to involve some sort of additional delay. This is something the Corps can ill afford given its now long-standing need for a replacement for the aging CH-53E fleet, which has suffered a number of high-profile crashes in recent years.

The Marine Corps says that the readiness rates of the CH-53E fleet have improved significantly in recent months, but has declined to disclose an actual mission capable rate. Instead, the service chose to highlight the Ready Basic Aircraft (RBA) rate, which is reportedly in the high 90-percent range. The Navy has officially described RBA as a “lowered bar” that simply refers to fixed and rotary wing aircraft that are flightworthy, but not even necessarily mission capable, let alone full mission capable, or “Code One,” meaning they can meet any assigned mission requirement.

“As the Echo [CH-53E] guy, I’m not worried at all,” U.S. Marine Corps Captain Christopher Harrison, a spokesperson for the service told USNI News in March 2019, insisting that the CH-53K was still on schedule for its first operational deployment between 2023 and 2024. “We’re healthier now than we’ve been in the last 35 years as a community, which is pretty significant.”

But while the Super Stallions may be in the best shape in recent memory, it would not necessarily take much for that community to note a dramatic improvement over how things have been since 2017, when mission capable rates slipped to less than 25 percent. Regardless, at a point, the helicopters will simply age out and the Marines won’t be able to wait forever for a replacement. The heavy lift support the CH-53Es provide right now is essential to the Corps’ operational doctrine and ensuring that there is no capability gap is critical.

The service looks to be staring down delays, and the hard decisions that come with them, whichever helicopter it ends up flying in the future.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com