It may take more than 15 years for workers to completely scrap the now-decommissioned aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, but the Navy is already recycling parts and raw materials from the ship. Components from “Big E” are already on certain Nimitz-class carriers and more could find their way onto new Ford-class carriers, including a future flattop that will also carry the name Enterprise.

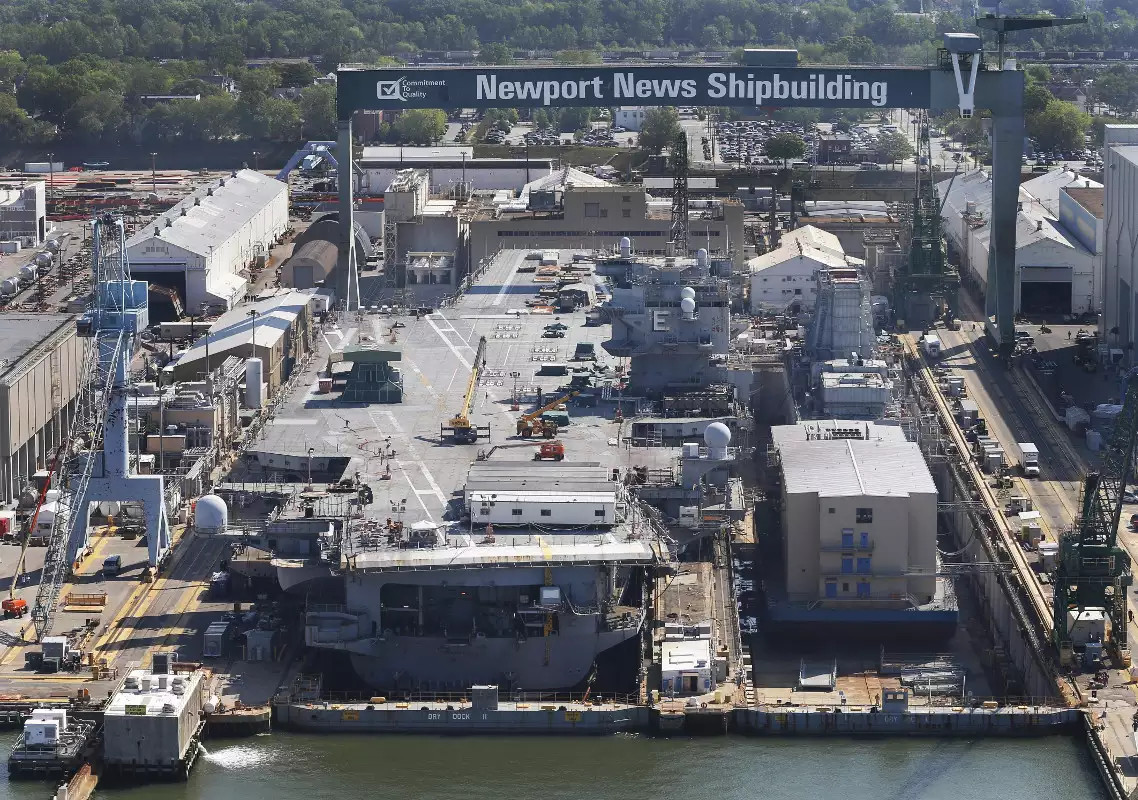

Defense One‘s Marcus Weisgerber and Brad Peniston got the details on how the former Enterprise will continue serving the Navy during a visit to Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding in Newport News, Virginia on May 1, 2019. The one-of-a-kind ship, the first ever nuclear aircraft carrier anywhere in the world, has been at the shipyard since 2013. The flattop had first entered service in 1961 and the Navy finally decommissioned her officially in 2017.

“She’s a unique [nuclear reactor] plant,” Chris Miner, Vice President of In-Service Carriers at Newport News, told Defense One. “But there’s still other things that are essentially very similar that we can leverage off of.”

When Newport News designed Enterprise in the 1950s, no one had ever built a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier before, so engineers had looked back to previous flattops that used multiple oil-fired boilers to drive the steam turbines that powered the ship, according to Defense One. But instead of boilers, they substituted eight relatively small nuclear reactors on Big E, two for each of its four propeller shafts. The subsequent Nimitz– and Ford-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, all of which Newport News has built, feature two larger nuclear reactors to provide the immense amount of power required for a modern supercarrier.

The complexities of Enterprise‘s dated and unique reactor plant design, coupled with the fact that no one has ever had to dismantle a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier before, has created a serious debate about how the service should proceed. The entire process of breaking down the ship and properly disposing of its reactors could take up to 15 years to complete and cost more than $1.5 billion, depending on what course of action the Navy chooses. You can read more about these particular issues in detail here.

As the Navy continues to consider its options, Newport News has already been stripping off parts of the ship to reuse and recycle. “We are harvesting as many parts as we can from the Enterprise… She’s still giving back even today,” Miner said to Defense One‘s reporters during their tour.

One of Enterprise‘s massive anchors is already installed onboard the Nimitz-class USS Abraham Lincoln. It’s not clear when this swap occurred, but Lincoln finished a major four-year rehab process, officially known as a Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH), in May 2017, three months after Big E’s decommissioning.

We don’t know whether the Enterprise uses the exact same anchor design as the Nimitz-class carriers did, at least initially, which weigh around 60,000 pounds each. The chains that hold the anchor, 12 of them in total, add another 20,500 pounds, but it’s not clear if Lincoln got those from Enterprise, too.

Regardless of the exact design, aircraft carrier anchors do not appear to have changed much since even before Enterprise entered service. As of 2003, the Nimitz-class USS Harry S. Truman was using the anchors from the conventionally powered first-in-class USS Forrestal, which the Navy had decommissioned in 1993.

Lincoln also received components from Enterprise‘s steam-powered catapults. Other catapult parts are now going into the Nimitz-class USS George Washington, which is presently at Newport News and is in the middle of its own RCOH.

The Navy has also taken back Enterprise‘s four 32-ton propellers, each of which has five blades. Newport News told Defense One that the Navy would refurbish and possibly use them again. The new Ford-class carriers do use a 30-ton five-bladed design. It is also possible that the screws could end up on display.

Lastly, Newport News has already melted down steel from Enterprise‘s hull to use in the keel of the future Ford-class carrier that will carry the same name. Commemorating old ships, or other notable objects, by incorporating them into the construction of new vessels is not without precedent.

Most notably, the hull of the USS New York, a San Antonio-class landing platform dock amphibious ship, includes steel that workers salvaged fallen World Trade Center towers in New York City, New York, in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In 2002, the Navy had approved the naming of the ship after the state of New York following a special request from then-Governor of New York George Pataki.

It seems likely that in the coming years, more components, and potentially additional raw materials, will make their way from Enterprise onto either existing Nimitz-class carriers or future Ford-class ones. The Navy expects the future Ford-class USS Enterprise to enter service in 2027.

If nothing else, there’s more than 60,000 tons of steel and another 1,500 tons of aluminum in the decommissioned carrier that could be salvageable. “I think it goes to how well the material on these ships are designed and built,” Newport News’ Miner told Defense One in reference to the ability to recover useful parts and materials from Enterprise on new carriers.

But whatever else happens, Big E is still finding ways to serve the Navy two years after its formal decommissioning.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com