Last week, Norwegian fishermen freed a beluga from an unusual harness with markings suggesting it had originated in St. Petersburg, Russia, prompting speculation that the Kremlin has been training these whales for military purposes in the Arctic region. The incident comes at a time when tensions between the Norway and Russia are particularly high, with Norwegian authorities having criticized their Russian counterparts multiple times in recent years over GPS jamming and conducting mock air strikes on a sensitive radar facility in Norway.

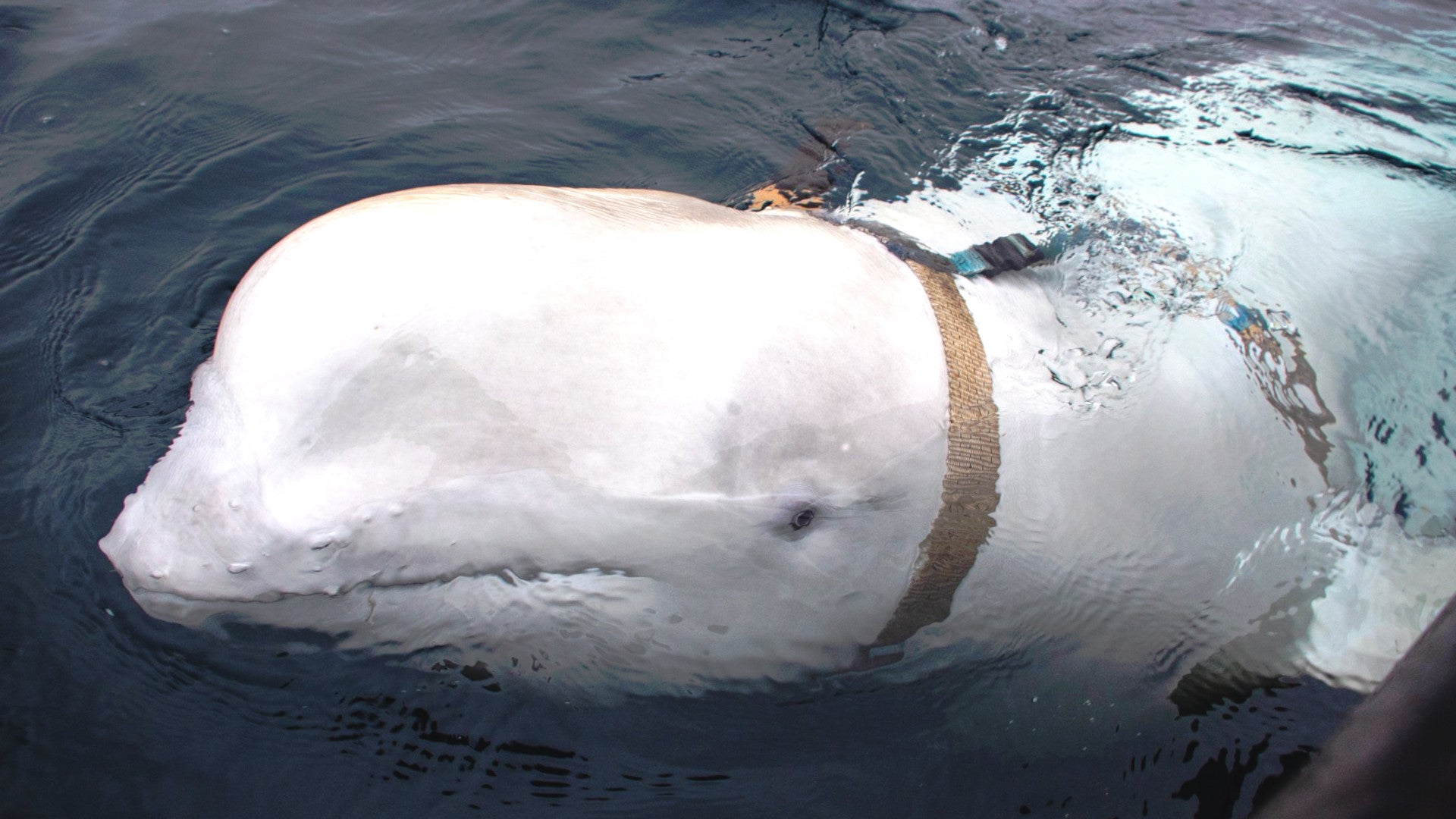

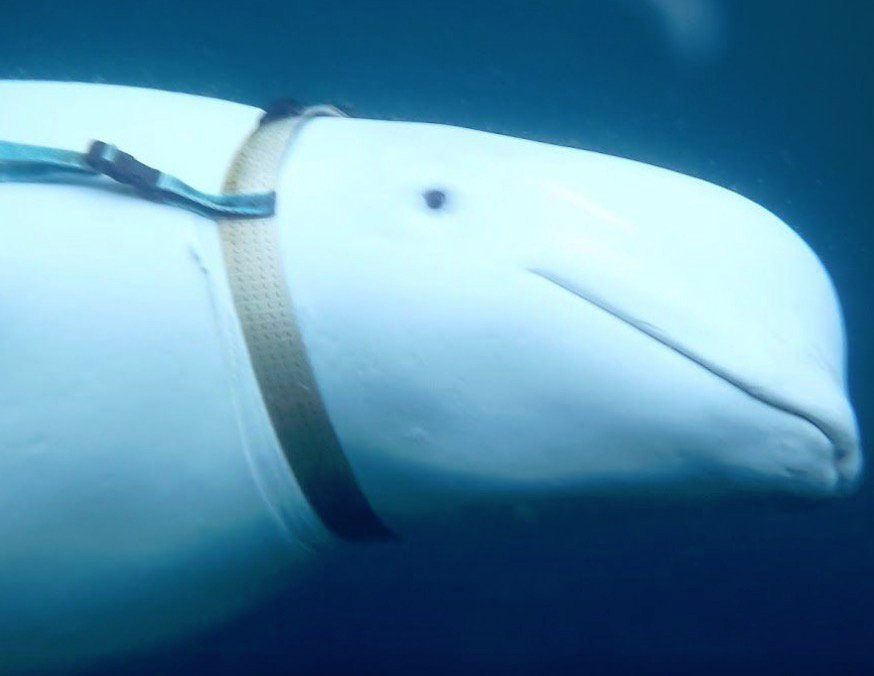

Norwegian state broadcaster NRK first reported on the events on Apr. 26, 2019. Fishermen saw the whale near Ingøy island in Norway’s far north Finnmark region on Apr. 24, 2019, and one of them eventually jumped into the water to cut the harness off, believing the beluga was in pain or having difficulty swimming. It was reportedly coming up to boats and scraping up along the side of them in an apparent attempt to get the gear off. Other individuals had reported seeing it in the same area as early as Apr. 22, 2019.

“It came over to us, and as it approached, we saw that it had some sort of harness on it,” fisherman Joar Hesten

told NRK, adding that it was very tame, suggesting that it had been in captivity for an extended period of time. “It always searches for boats and people, and then it comes all the way to the boat and tries to rub the straps off.”

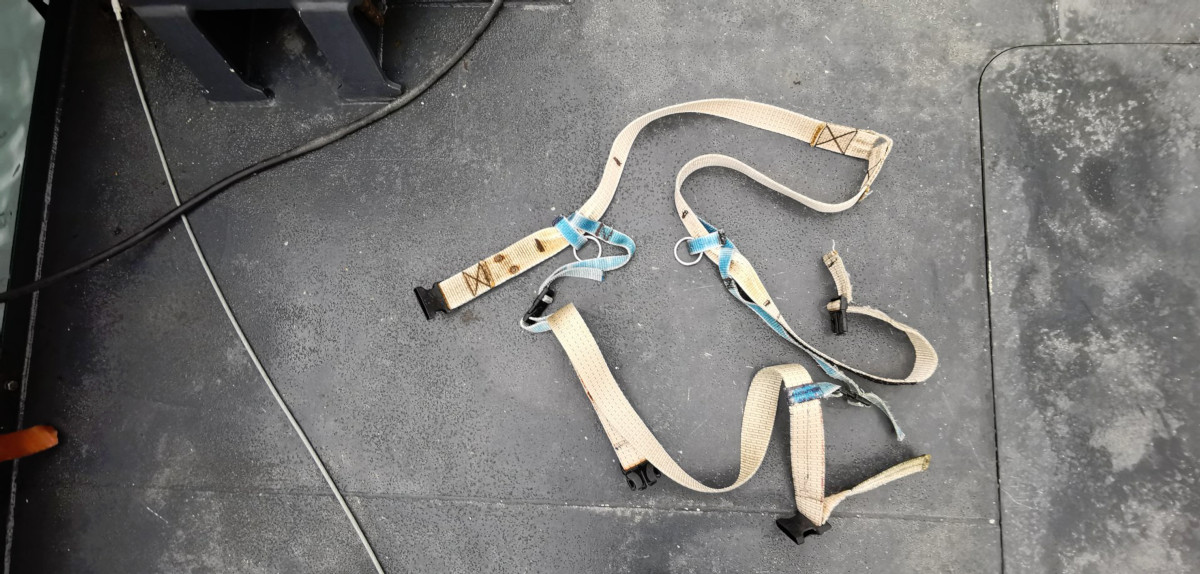

The exact purpose of the harness is unclear. It appeared to have some sort of mount on it that could accommodate a small camera or another piece of equipment, though there was no such system present when the fishermen cut it off and recovered it, according to NRK. The Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, or Fiskeridirektoratet, also released a picture showing what appeared to be a hook, which the whale could be trained to use to grab objects.

Other photos from the Fiskeridirektoratet show that one of the buckles has “Equipment” and “St. Petersburg” molded into it in Roman script, along with an unidentified logo. It does not, as some reports have suggested, appear to include the full phrase “Equipment of St. Petersburg.”

“I have colleagues here who put satellite tags on white whales [belugas], but they do not use this type of equipment. I have never seen anyone doing research this way,” Martin Biuw of the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research told NRK. “If this [whale] comes from Russia, and there is great reason to believe it, then it is not Russian scientists, but rather the [Russian] navy that has done this.”

Trained belugas could certainly have military value, given their ability to swim and dive comfortably even in the extremely cold waters above the Arctic Circle and traverse long distances. In captivity, the whales have shown the ability to swim down to depths deeper than 1,900 feet and, in at least one instance, all the way down to 2,860 feet. This is far deeper than human divers and even many submarines can manage.

A beluga trained to hunt for and spot certain objects and equipped with a camera would potentially be able to conduct certain underwater reconnaissance tasks, including locating underwater sensors and mines. They might also be able to inspect ships in port or help guard maritime facilities against enemy divers and saboteurs.

There is certainly precedent for this. The Soviet Union had a naval marine mammal program based in the Black Sea during the Cold War, which focused primarily on training dolphins for the same kind of underwater tasks.

After the Cold War ended, the remnants of this program ended up Ukraine and languished. After Russia illegally seized Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014, what was left of the infrastructure, as well as reportedly some trained dolphins, returned to Russian control. All of these dolphins reportedly died, with Ukrainians saying the animals had been unwilling to perform for their new masters and Russia countering by saying the animals had been poorly cared for, to begin with.

Marine mammal programs are hardly limited to Russia, either. The U.S. Navy continues to train both bottlenose dolphins and sea lions as part of its own Marine Mammal Program. As with the Russians, these animals and their handlers primarily train to find objects underwater, such as mines, and guard against hostile frogmen.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union studied the use of belugas in the past, but there has been no evidence previously of those programs reaching an operational state. Given the increasing strategic significance of the Arctic region and the Kremlin’s very public push to increase its military presence and operational capacity above the Arctic Circle, it would hardly be out of the realm of reason for the Russians to at least re-investigate the practicality of using these whales for military purposes.

The “St. Petersburg” marking on the harness would not have to mean that the unit responsible for these animals is based there, either. The city is home to the Russian Navy’s top headquarters, but Russia’s Northern Fleet operates from a constellation of bases on the White Sea and the Barents Sea further to the north. There are reportedly two facilities in Murmansk on the Barents Sea that are contributing, or have in the past, to Russian military marine mammal programs.

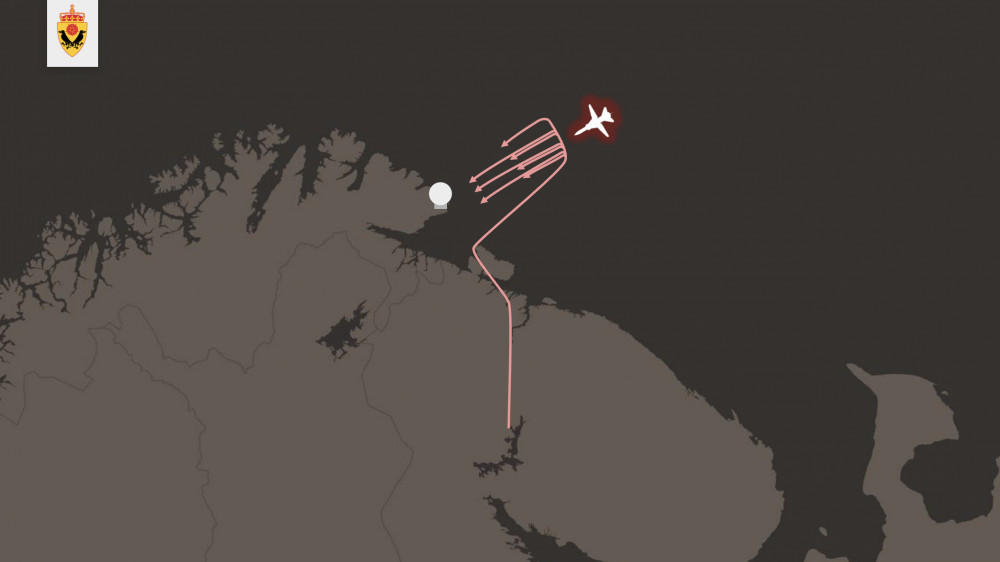

It would not be unreasonable to assume that the Russians could be training to use the marine mammals in and around Norway or that the whale simply escaped from a training exercise in the region. On Apr. 25, 2019, the Russian Navy’s Northern Fleet did announce it had concluded a major drill involving 20 ships in the Barents Sea, though there was no mention of marine mammals participating.

In the past few years, both Russia and NATO have stepped up military exercises in and around Scandinavia. Norway has blamed electronic warfare systems taking part in the Kremlin’s drills in its northwestern regions for GPS outages in Finnmark on multiple occasions.

In addition, for two years running now, the Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS), also known as the Etterretningstjenesten or E-tjenesten, the country’s top military intelligence agency, has accused the Russian military of provocative exercises involving mock air strikes against a secretive radar installation in the coastal town of Vardø, which is also in Finnmark. This array reportedly has ballistic missile defense and other intelligence gathering capabilities, though the Norwegians insist it is only for monitoring general air and space activity.

Still, if the beluga is part of an as yet unacknowledged Russian Arctic marine mammal program, it seems curious that the buckle would so conspicuously include an apparent link to Russia, but also include writing Roman script instead of Cyrillic. It is possible that this is specifically to allow for plausible deniability.

There may be more innocuous explanations for the harnessed beluga, that are still linked to Russia, too. In February 2019, Russia’s Federal Security Service, better known by the Russian acronym FSB, raided a fish farm in the country’s far east and seized 11 orcas and 90 belugas that had been living in cramped, squalid conditions ahead of sale to aquariums in China.

An online campaign that American actor and activist Leonardo DiCarpio had led was credited as helping push Russian authorities, and President Vladimir Putin himself, to act. However, by March 2019, there was still disagreement about how, where, and when, to release the whales. However, There is no indication that those whales have gotten released yet and there no evidence a harness like the one seen on the beluga near Ingøy would be part of a release operation.

In addition, the Russian government has given the people of the village of Nil’moguba special license to capture belugas to train and then sell to aquariums and waterparks. Nil’moguba is located in the semi-autonomous Republic of Karelia, which sits on the white sea, and is less than 1,000 miles by sea to Ingøy island.

So far, the Kremlin has not issued any statement of its own on the matter. The circumstantial evidence is compelling, but there’s still too little information to say for sure that a trained Russian Navy “military whale” has escaped, or whether a captive beluga might have gotten free from civilian handlers.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com