Outgoing Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson says the United States may need to conduct a show of force to deter opponents, such as Russia and China, from attacking U.S. military satellites in space. But it wasn’t entirely clear whether this would involve demonstrating the ability to attack an adversary’s own space assets only or if it would even show an ability or willingness to attack hostile space-based systems at all. This cuts to a larger issue, that no one really knows for sure what a war in space would actually look like, though the United States is certainly working to answer that question.

Wilson offered her view on the future of potential conflict in space to reporters on the sidelines of the Space Foundation’s 35th annual Space Symposium, which began on Apr. 8, 2019. Other Air Force and U.S. officials have also used the event as an opportunity to highlight the very real and growing threats to vital satellites that support critical military capabilities, such as long-distance communications, navigation, weapon guidance, early warning, ballistic missile defense, and intelligence gathering. Defending those assets has been an increasingly hot topic in recent years and President Donald Trump’s administration has gone so far as to propose the creation of a sixth military branch, the Space Force, to focus on these issues.

“There may come a point where we demonstrate some of our capabilities so that our adversaries understand they cannot deny us the use of space without consequence,” Wilson said, according to The Daily Beast.

“That capability needs to be one that’s understood by your adversary,” she added, according to Air Force Magazine. “They need to know there are certain things we can do, at least at some broad level, and the final element of deterrence is uncertainty. How confident are they that they know everything we can do? Because there’s a risk calculation in the mind of an adversary.”

Wilson wasn’t the only one to warn that the United States might retaliate forcefully in response to an attack on U.S. military space-based systems. “It’s not enough to stand in the ring and take punches. You have to have the will and capability to punch back,” U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff David Goldfein also said at the Space Symposium.

As The War Zone has pointed out on multiple occasions, the threats to U.S. military space assets are very real. The U.S. military’s historical advantages in space-based capabilities and its increasing reliance thereon has long made them attractive targets to potential adversaries, such as Russia and China.

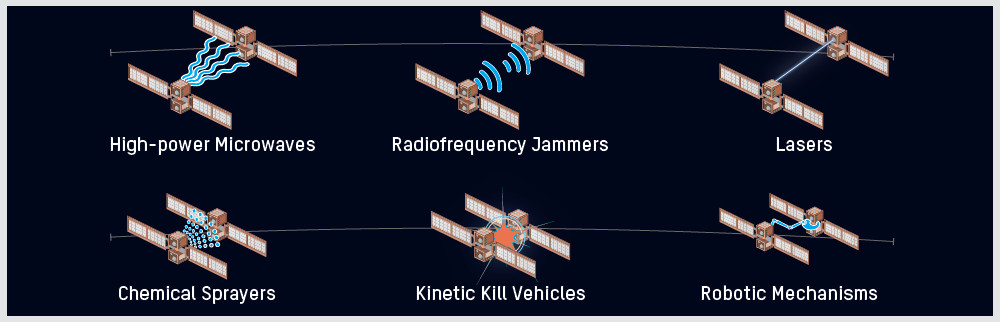

Most recently, there have been reports that China may be working on ground-based laser weapons to blind or otherwise disrupt optical systems on U.S. satellites, including ones tasked with missile warning and intelligence gathering missions. On Apr. 9, 2019, at the Space Symposium, Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan said that the United States is of the opinion that the Chinese will have an operational anti-satellite laser capability by 2020. A report from the Defense Intelligence Agency in February 2019 said that China may be able to actually damage or destroy a satellite with a laser system by the mid-2020s.

In December 2018, Russia announced that they had put a ground-based laser system, called Peresvet, into service. The Russians claim this system could have an anti-satellite role and also say they are developing an aerial anti-satellite laser system.

This is to say nothing of the various anti-satellite interceptors and potential small “killer satellites” Russia and China have also deployed. In March 2019, India demonstrated its ability to shoot down a satellite, which shows that these capabilities are only proliferating.

Secretary Wilson declined to say what specific offensive capabilities the United States might employ as deterrents against attacks on U.S. military satellites, or if it had any such systems in place now. In February 2019, the Air Force did wrap up a four-month study into the issue, according to Air Force Magazine.

“We looked at all of our missions in space, from missile warning to communications and intelligence collection,” Wilson said at the Space Symposium. “We took the best estimates of the threat and presumed a thinking adversary who would respond to the actions that we take.”

This process involved thousands of wargames and at least 25 tabletop exercises involving not only Air Force personnel, but individuals from other military branches, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). These exercises also included simulated means of mitigating the threats, including the use of disaggregated constellations of hundreds or potentially thousands of small commercial satellites to make it more difficult for an opponent to swat down an entire network. Air Force Secretary Wilson has suggested that the results did not reflect favorably on this idea, which the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the newly minted Space Development Agency have been keen to promote.

While we don’t know what responses the U.S. military might already have or be considering, we do know that it has demonstrated its ability to shoot down a satellite with an air-launched interceptor in 1985 and with a surface-launched missile in 2008. The latter event was known as Operation Burnt Frost. In 1997, it also conducted a test of a ground-based laser weapon that may have at least blinded or otherwise temporarily disrupted the optics on a target satellite.

The U.S. military also has a congressional mandate at present to be developing space-based missile defense systems. Many of the concepts on the table now would have an inherent anti-satellite capability. But officially, the United States does not have an anti-satellite system deployed and it has never described any past developments and experiments as offensive in any way, despite their obvious potential applications.

Of course, neither Wilson nor Goldfein specifically said that any potential retaliatory attacks would have to be limited to targets in space, or necessary include them at all. An American response to an attack in space could include conventional strikes, or even potentially nuclear ones if the damage done to U.S. space-based systems were to have sufficiently severe impacts on the ability of the United States to continue functioning as normal.

There could be non-kinetic options, as well, including offensive cyber attacks. Either kinetic or non-kientic options could be focused specifically on disabiling an opponents ability to control their own space-based systems.

This all leads to the bigger question of what conflict, or even in isolated attack, looks like in space and what a proportional response would be if one were to erupt. What kind of attack prompts what level of retaliation? Is an opponent temporarily disrupting a satellite’s operation enough to warrant a kinetic response?

What if an adversary destroys a top-secret satellite the very existence of which is classified? What if that was a weapon you hadn’t publicly acknowledged you already had? What if you can’t tell where the attack came from or who is responsible?

These are hardly new questions.

“It’s really difficult to go ahead and justify how you might attack somebody’s homeland if they’ve taken out a satellite that you don’t even admit exists,” Douglas Loverro, then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, said during a talk in 2016. “Is jamming an attack? Is a laser an attack? Does it have to be a kinetic hit on a satellite to be an attack?”

“None of us actually know how a war – if and when it extends to space – will actually evolve, where and what phase will it happen, when will it happen in the conflict, how will it be engineered, we don’t know any of that,” he continued. “It’s difficult politically, it’s difficult emotionally. Probably people are going to die on the ground where nobody’s going to die in space.”

Actually destroying something in space in a retaliatory strike may not even be a realistic option. Blowing up a satellite can only create a cloud of extremely fast flying debris that is impossible to control and could threaten other friendly military and civilian space assets, as well as enemy targets.

The world is grappling with that particular issue right now in the aftermath of India’s anti-satellite interceptor test. The debris field from that event presents a serious threat to objects in low earth orbit and may not fully dissipate for up to 18 months.

Of course, there are various ways to disable a satellite without necessarily creating a ton of dangerous space junk. Small, highly maneuverable “killer satellites” might be able to use manipulator arms to deorbit a target so that it simply burns up in the atmosphere or just damage key components without breaking any significant parts off in the process. A laser or another type of directed energy weapon could similarly render a satellite non-functional without having to shatter it.

The goal has to be to “ensure an attack on space has no benefit to our adversaries,” Loverro said. “At the end of the day, what really deters people from going ahead and attacking the U.S. is the notion that the U.S. can bring the other domains into a conflict and defeat any aggression that we may see against the United States.”

But Wilson’s and Goldfein’s comments now seem to suggest something in that calculus has changed. The recent wargaming and tabletop exercises may have at least indicated that the threat of some tertiary action may not be enough to actually deter an opponent from launching an attack on U.S. assets in space, or thinking they might be able to get away with something short of completely destroying a satellite.

What is clear is that space is becoming an increasingly dangerous place and that the U.S. military wants to make clear that it will not take threats to its assets there lightly. What an American show of force – or an actual hostile act in space its meant to deter – might look like remains to be seen.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com