The U.S. Navy has at least tested small hydrofoil boat based on the VT Halter Marine Mk Mod 2 High Speed Assault Craft, a predecessor to the service’s stealthy Combatant Craft Assault special operations watercraft, or CCA. The revelation comes more than 25 years after the service retired its six Pegasus-class missile boats, the last of its operational hydrofoils.

The existence of the hydrofoil design first emerged in a video that the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Carderock Division, or NSWC Carderock, posted on YouTube on Mar. 12, 2019. A clip showing the small boat moving at high speed is part of a larger montage of clips of the center’s work attached to the Navy’s “Forged by the Sea” recruitment commercial.

There is no narration to the Carderock clips or other descriptions of the systems shown, but the craft in question is clearly based on the VT Halter Marine design, if not a direct hydrofoil conversion of one of these high-speed special operations craft. The standard Mk Mod 2 High Speed Assault Craft is just under 40 feet long with a hull primarily made of kevlar and a pair of high-performance engines.

The hydrofoil is seen in the video below at around 2:27 in the runtime, if it doesn’t forward you automatically.

Carderock, which is situated in Maryland along the Potomac River, specializes a variety of ship design fields, including hullforms and radar and other signature reduction. The center’s work has included experimental ships such as the Advanced Electric Ship Demonstrator (AESD), also known as the Sea Jet, which is a functional quarter-scale model of a DDG-1000 Zumwalt-class stealth destroyer. The full video also includes clips of testing of other subscale ship and submarine design models, including experiments with a hullform similar to that of the M80 Stiletto experimental stealth boat.

We don’t know how many hydrofoil derivatives of the Mk Mod 2 the Navy has, or had, or if this is, or was, part of a more extensive program to develop a new special operations boat. At the time of writing, Carderock had not yet responded to The War Zone’s queries about this design.

The Navy appears to have largely replaced the Mk Mod 2s in operational units with the newer CCA, which is a stealthy 41-foot long boat with a composite material hull and two engines, which you can read about in more depth here. The service acquired these boats from U.S. Marine, Inc. as a follow-on to the earlier High-Speed Assault Craft. VT Halter Marine and U.S. Marine had collaborated on projects during the 1980s, including the Mk V Special Operations Craft (SOC), before parting ways. In 2014, a disused and hard-worn Mk Mod 2 even sold on eBay.

There are some of the Mk Mod 2s still in service, however, and they are still available for training purposes. The boats most recently turned up at an exercise off the coast of Miami, Florida that The War Zone was first to report on and appeared to involve members of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG).

If the Mk Mod 2s are indeed largely or completely out of front-line service, they would be ideal platforms for experimental projects. A hydrofoil high-speed assault boat could definitely offer Navy special operators certain advantages.

Hydrofoils use wing-like structures underneath the hull to lift the hull out of the water and “fly” above it. This reduces drag that ships would otherwise experience if they had to cut through the water during traditional “hull-borne” sailing.

As a result, hydrofoils are generally faster and often have better fuel economy than similarly-sized traditional designs. They can also offer added stability, even in rougher sea states, since they’re sailing above the waves, rather than crashing through them. It also largely eliminates the skipping motion common in many other high-speed boat designs, such as the CCA itself, which can be extremely hard on crew and passengers, especially during extended duration missions. This same elevated position can offer added protection against shallow-water mines and other hazards, too.

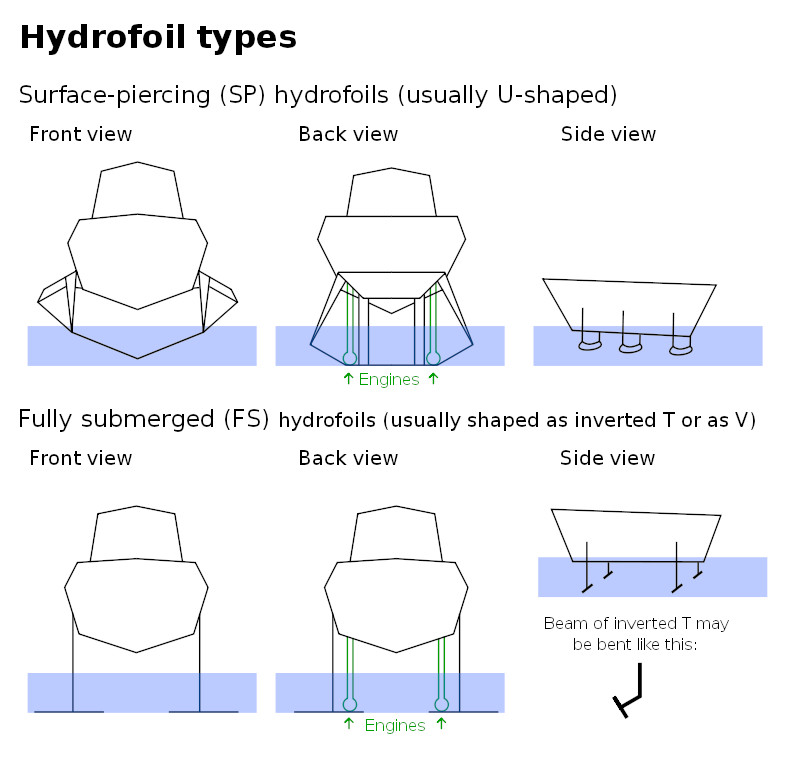

There are two general design categories of these ships, one involving what are known as surface-piercing foils and another using so-called fully-submerged foils. Surface-piercing refers to the fact that these designs generally have foils that remain partially above the water.

Surface-piercing is the simpler of the two general configurations and is more common on commercial hydrofoils, but it can still produce significant drag due to the size of the foils. Fully-submerged foils are typically smaller and offer improved performance.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Navy experimented extensively with a number of surface-piercing and fully-submerged hydrofoil designs. The service even sent two prototype gunboat designs with fully-submerged foils, the Grumman-built USS Flagstaff and Boeing-made USS Tucumcari, for trials during the Vietnam War.

The Navy also had a number of experimental hydrofoil craft, primarily with fully submerged foils, including the USS Plainview. Lockheed delivered this ship in 1969, which at the time was the largest hydrofoil in the world with a displacement of more than 300 tons. Flagstaff, Tucumcari, and Plainview, among others, are seen in the video below.

While we don’t know the performance specifications of the standard Mk Mod 2, Carderock’s hydrofoil derivative, which is a fully-submerged design, could have significantly better speed and range than its traditional counterpart, as well as improved capabilities on the open ocean. The Navy’s missions for the newer CCAs include inserting and extracting special operators, as well as conducting discreet coastal surveillance missions, according to an official briefing. They have also been employed as stealthy platforms to deliver teams to board larger ships. In recent years, the existing stealthy speed boats have appeared in the Middle East, off the coast of the Horn of Africa, and in the Pacific Region.

With greater speed and range, a hydrofoil fast assault craft could be more flexible, especially during short-notice extraction missions. The CCAs also operate from motherships, such as the secretive M/V Ocean Trader, which could use hydrofoils instead to launch missions from a point further away from shore, potentially reducing the possibility of detection and the risk of counterattack.

Once the craft got closer to shore, the crew could revert to hull-borne operation and close the final distance in a low-profile, reduced-signature mode. They could also remain in the foil-borne configuration to better navigate shallow littoral environments or those where there might be an elevated threat of mines or other hazards.

But there are potential disadvantages, too. Surface-piercing hydrofoils are typically “self-righting,” meaning that the ship will remain stable even if there is a sudden loss of speed and lift that leads to a “crash landing” of sorts. In contrast, fully-submerged foils require constant attention from the crew, usually with the help of a complex computerized control system, to maintain stability.

Beyond that, fully-submerged hydrofoils often have two sets of propulsion systems, one for hull-borne and foil-borne operation, which can make them even more complicated and labor-intensive to maintain. This generally involves propellers or water jets at the base of the main foil, in addition to a traditional propulsion arrangement.

Hydrofoils can sometimes have trouble operating in shallower harbors and inshore areas in the hull-borne mode. The designs often include mechanisms to swing the foils out of the water during hull-borne operation, further adding to the overall complexity. Even with retractable foils, air-dropping a hydrofoil CCA derivative, something that boat is capable of in its present form, would probably be a challenge.

This all makes hydrofoils more expensive as a result, too. The costs involved have made building hydrofoils above a certain size largely impractical. As noted with Plainview, even larger military examples are exponentially smaller than traditional warships, typically being in the size range of conventional gunboats and missile boats.

These realities colored much of the Navy’s previous experiences with hydrofoils. The service quickly withdrew Flagstaff and Tucumcari from South Vietnam because they were too complex for maintenance facilities there.

In 1972, Tucumcari hit a coral reef off the coast of Puerto Rico during a test, sheering off the main foils and injuring multiple members of her crew. The ship was so badly lodged in the reef that salvage teams tried to free her by using explosives to break up the coral, but this only further damaged the ship. The Navy formally struck the ship from its rolls in 1973 and sold it for scrap.

Flagstaff served longer, including a stint on loan to the U.S. Coast Guard, but headed to the scrap yard itself in 1978. Plainview met the same fate that year.

These ships did serve as a stepping stone to the Navy’s plans for a more robust hydrofoil force. In the late 1960s, it had joined with its NATO counterparts in Germany and Italy to develop a hydrofoil missile boat. The service envisioned the ships dashing out to strike Soviet surface vessels in the North Sea and Baltic Sea with Harpoon anti-ship missiles.

Boeing received the final contract to design what became the Pegasus-class. These ships displaced around 237 tons and each had a 76mm main gun and could carry up to eight Harpoons. The German examples were to have come equipped with the French-designed Exocet anti-ship missile, instead.

But Germany and Italy eventually dropped out of the program, while other potential partners, including the United Kingdom and Canada, declined to join the effort. The Navy, which had planned to buy as many as 30 of the new Pegasus-class ships from Boeing, ultimately purchased just six.

Pegasus and her sisters instead went to Key West, where they primarily spent their service searching for drug runners in the Caribbean. The ships, which could reach top speeds up to 55 miles per hour and had a range of at least 750 miles, were well suited to chasing down smugglers’ speed boats. In 1993, the Navy retired all six of the hydrofoil missile boats, the first of which had entered service in 1977.

Now, more than two decades later, Carderock’s hydrofoil Mk Mod 2 derivative might be a sign of renewed interest of the hydrofoil concept within the Navy, in general.

Author’s note: NSWC Carderock took down the original video for unknown reasons and a copy is now in its place in this story.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com