A number of Idaho citizens and an environmental conservation group are suing the Air Force in the U.S. District Court of Idaho in an attempt to stop them from using Idaho cities and towns as settings for urban close air support exercises. The complaint alleges that the Air Force didn’t go far enough to inform local residents about the drills and of the supposed hazards they bring to their communities. At the same time, it is crystal clear why the training is needed and it really isn’t something that can be provided on most gunnery ranges, such as the nearby Saylor Creek range where F-15E Strike Eagles from Mountain Home AFB regularly train.

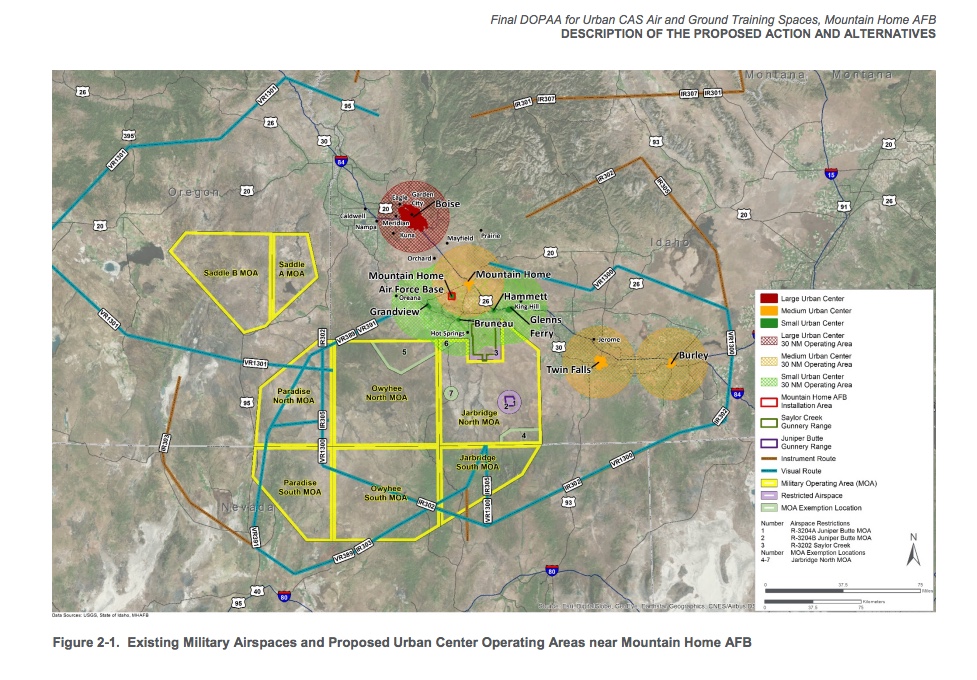

As it sits now, there would be up to 160 training days related to the program per year. Towns in Southwestern Idaho would be the primary locales for the exercises, but other locations in Idaho may also to be used. The Idaho Press has kept a watchful eye on the issue, and describes the training as such:

Those war games, or “training events,” would include unarmed members of the military dressed as plainclothes civilians stationed in some of southwestern Idaho’s urban locations, such as downtown Boise. Military personnel on the ground would communicate with U.S. Air Force planes overhead, and the two groups would work together to find targets, which aircraft would identify with “low-power, eye-safe lasers,” according to a document released by the U.S. Air Force. The training events might take place during the day or at night, and U.S. Air Force officials have stressed the need for training to take place in a city setting to simulate “urban environments encountered in combat.”

…

Months ago, officials from the 366th Fighter Wing at Mountain Home Air Force Base proposed a regimen of “urban close air support training.” It’s a style of training the military has used since the 1990s, and it’s designed to prepare military personnel to fight in cities and towns.

The training mixes military personnel with civilians in the community, but because those personnel are dressed as everyday residents, and are “trained to behave in a manner typical to any community member to avoid drawing attention to themselves or the operations,” residents may be unaware the training is taking place. Military personnel would drive unmarked cars and travel through public spaces. The training would not include any weapons, according to military documents.

“Ground support teams would not interfere with civilian traffic or pedestrians,” according to the military’s environmental assessment, and military personnel would obey all local laws where the training would take place.

The training would require planes to fly between 10,000 and 18,000 feet to various locations in southwest Idaho, including many in the Treasure Valley. In general, according to the project’s environmental assessment, two military aircraft would be in the air above a town or city at a time, communicating with military members on the ground.

…

Initially, authorities at Mountain Home Air Force Base pushed for the plan to allow 260 training days a year but “decided to reduce the proposed number of operations by approximately 40 percent following coordination with stakeholders and public communities during scoping events,” according to the environmental assessment.

…

The Air Force has emphasized the need to train in the “urban canyons” created by tall buildings, and Boise is by the far the largest city in the massive swath of proposed territory where the training would take place.

Training for Military Operations In Urban Terrain (MOUT) has taken on a whole new level of importance in recent years as the Pentagon grapples with a future in which it thinks wars will be fought mainly in so-called “megacities.” Training units to integrate air combat asset into these extremely complex combat environments is a key part of preparing for these types of contingency operations.

The Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs) that are tasked with this challenging work are the nexus between the airpower above and the forces on the ground and guide aircrews onto precise targets in dense urban environments. Technology is helping to speed up the time it takes from the initial radio contact between aircrews and JTACs to weapons impacting targets, but “talking crews onto a target” and using laser spotting systems are still the nuts and bolts of this very high-stakes business. You can see and hear this coordination for yourself in this past piece of ours.

Accomplishing this in an urban setting where the variables drastically increase and simple issues like tall buildings blocking an aircraft’s targeting pod’s line of sight to the target or even the flight path of a weapon, or communications issues caused by tall buildings, or clearly distinguishing friend from foe can become robust challenges to overcome. The chances for collateral damage, in particular, skyrocket in urban close air support setting and so many factors have to be taken into account before a weapon is launched. For instance, a prime target may be easily struck, but if it is next to a hospital, house of worship, or a school, doing so may be against the rules of engagement or may cause more harm than good.

The USAF laid out why it needs this training in its detailed environmental assessment and action plan for the exercises:

Urban CAS operating environments typically range from small towns to large cities with corresponding extents of vertical development (e.g., tall buildings), population sizes, and cultural and community dynamics. During combat, aircraft commonly provide supporting firepower inoffensive and defensive operations to destroy, disrupt, suppress, neutralize, or delay hostile forces. The speed, range, maneuverability, and selection of integrated weapons systems of the aircraft involved allows CAS assets to attack targets that other friendly and allied forces may not be able to engage effectively (JCS 2014). When conditions for air operations are permissive, CAS can halt enemy attacks, help create breakthroughs, destroy targets, cover retreats, and guard flanks. While achieving these objectives, air and ground operations must be conducted in accordance with Department of Defense Directive 2311.01E, DoD Law of War Program and Rules of Engagement (ROEs), which specifies that U.S. military forces will adhere to the following guidelines:

• Act with proportionality, replying to hostility with only as much force as needed to eliminate the enemy

• Distinguish combatants from noncombatants, and distinguish military objectives from protected places to minimize collateral damage

• Prevent unnecessary suffering by safeguarding certain fundamental human rights of those involved in a conflict.

The planning and execution of Urban CAS missions is difficult because these missions either require or inevitably involve the following:

• operations in “urban canyons” (i.e., artificial canyons created by multistory buildings)

• deconfliction of multiple aircraft operating within a confined airspace

• operation in accordance with the ROEs

• difficulty in threat analysis because of information, environmental, and visibility constraints

• overload of visual cues associated with civilian traffic, presence of buildings, and varied landscape

• presence of noncombatants proximal to identified threats

• potential for collateral damage during engagement

• increased risk of friendly fire with other allied air and ground teams in the area (JCS 2014). These operational circumstances cause tactical difficulties in properly identifying and locating potential targets while discerning and protecting Friendly Forces (FFOR). Both are critical for successful execution of Urban CAS missions. Readiness for Urban CAS missions requires that air and ground crews train intensively to gain practical experience responding to the following situations:

• Loss of, or inability to maintain, communication. Urban terrain inhibits communications equipment and can absorb or reflect transmitted signals.

• Difficulty identifying targets. Vertical development makes it difficult for aircrews to identify target combatants and may require specific positioning and orientation attack headings to achieve line-of-sight with an identified target. Ground-level observers may be positioned on upper floors of buildings to improve visibility. In these situations, ground teams (e.g., JTACs) mark and designate their positions or CAS target locations visually with an infrared laser pointer, electronically with a Global Positioning System (GPS) grid, or with a gridded reference graphic to guide aircraft tracking.

• Difficulty maneuvering aircraft over urban terrain. Aircraft navigation over and through urban terrain can be more difficult than over natural terrain because maps do not show vertical development of urban terrain.

• Requirement for navigational aids. Rapid movement from position to position can create confusion between aerial and ground observers as to friendly and enemy locations. Familiarity with the characteristics of urban terrain allows aircrews to discern key features in this environment. Navigational aids, such as GPS, have reduced but not eliminated this challenge. The use of the GPS and handheld laser pointers or designators eases the problems associated with night navigation, orientation, and target identification.

• Conditions of limited visibility. Limited visibility may occur because of fog, smoke, or dust on the battlefield, but occurs most frequently because of operations extending into hours of darkness. Night navigation systems may be degraded because of interference induced by buildings and enemy GPS jamming equipment. Ability to provide CAS during times of limited visibility and adverse weather demands a higher level of proficiency that can only come about through dedicated, realistic CAS training. Aircrews and JTACs must routinely and consistently train together during such conditions to overcome visual limitations when the aircrew have only sensors and systems to guide them.

• Artificial lighting. Rapidly changing lighting conditions from day/night operations and the effects from operating within terrain with artificial lighting impacts how the target presents against its background and the measures required to ensure an aircrew can distinguish it from its surroundings. Additionally, the artificial lighting of urban environments can limit the usefulness of night vision equipment because lights from buildings, streets, airports, and industrial areas can create glare and reduce visibility (JCS 2014).

Considering Mountain Home Air Force Base houses three squadrons (two USAF and one training unit for the Republic of Singapore Air Force) of F-15Es—one of America’s most capable CAS platforms—providing this level of real-world training very nearby would be extremely beneficial. Otherwise, the aircraft would have to constantly deploy to other bases in order to receive similar training, and, even then, it will still be in someone’s “backyard.”

Saylor Creek Range nearby does have a Military Operations In Urban Terrain (MOUT) site, but it is austere and doesn’t feature larger multi-story buildings or a very complex layout, which only a handful of MOUT sites do across the country. Still, even the biggest MOUT site can’t compete with operating in an actual built-up city or town. It just isn’t something you can simulate to a high fidelity. That is why special operations teams and the 160th Special Operations Airborne Regiment (SOAR) constantly train in some of the biggest metropolises in the United States. It always causes a stir in the communities they descend on, but it is absolutely essential training that can’t be had anywhere else.

The USAF impact study describes the training operations as such:

For Urban CAS proficiency training, a “training event” is a collection of “training operations” that would take place at a single urban area on a given day (i.e., 24-hour period). Therefore, discussion in this EA may interchangeably address training events as training days. A typical sortie would be defined as the round-trip, or, a departure and return flight of a single aircraft to the installation. Each leg of a sortie would be defined as a flight operation. During a training operation, 2 (or a maximum of 4) aircraft would depart the installation, enter the CAS wheel outside of an urban area, enter the urban center airspace to conduct training (for a duration of 60 to 90 minutes), then returning to the installation. Thus, a training operation would involve 2 (or a maximum of 4) sorties.

Generally, only two aircraft would be in the urban center airspace at one time. However, fulfillment of proficiency training in operational transitions (or, “hand-offs”) from one pair of aircrews to another pair of aircrews would require presence of 4 aircraft in the CAS wheel. During an operational hand-off, the aircrew from a pair of aircraft that actively tracking in the urban center airspace would communicate status of the operation to the aircrew of the two aircraft remaining in the CAS wheel. Then, the aircraft in the urban center would exit to the CAS wheel, and the aircraft waiting in the CAS wheel would enter the urban center to continue the tracking effort.

Each training operation would be followed by a 2- to 3-hour period of no flight activity during which ground support teams would organize for the next training operation. A training event may involve day or a combination of day-night training operations. Day training would occur between the hours of 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. Night training would occur between the hours of 10 p.m. and 7 a.m.

…

Prior to mission training operations, F-15E aircrews would maintain flight in a circular path, known as a CAS wheel, in the airspace that overlies the farther outskirts of town or the outermost edge of the 15-NM radius from the urban center point.

…

Ground teams would be working within the urban center in accordance with their particular force position (FFOR or OPFOR). To begin a mission scenario, members of the FFOR team would contact aircrews flying in the CAS wheel with a request for air support to identify and locate a hostile threat. The aircraft would separate from the CAS wheel, fly toward the urban center point, and be guided with instrumentation and communication to identify, track, and simulate neutralization of the OPFOR. The two aircraft would fly throughout the airspace overlying the city in a wedge formation where the lead aircraft would be positioned at a lower altitude and ahead of the second aircraft. The second aircraft serves to cover the lead aircraft from a higher altitude and reasonable distance behind, where visibility surrounding the first aircraft can be maintained. Flight tracking of OPFOR would continue until the point of simulated weapons fire. Upon mission completion, the aircraft would return to the installation.

…

Aircrews would use the on-board weapons firing simulation system to mock bomb identified targets. The proposed training operations would not involve use of weapons to fire munitions. Munitions would not be loaded on the F-15Es that are flown during the proposed proficiency training operations. Ground teams would not carry weapons. All interactions between air and ground teams would be achieved through use of electronic equipment including tactical communication radios (e.g., frequency modulation, very high frequency, ultra high frequency, and satellite communication), navigational GPS for maintaining awareness of target locations, low-power, eye-safe infrared training lasers for marking targets, and computer simulation systems on board the aircraft.

Clearly, there is zero chance of a bomb or missile accidentally being launched on a civilian area. The aircraft are totally unarmed. But they won’t be silent overhead. The assessment also notes that 25 percent of the missions would occur at night, with activity occurring from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m.

The 190th Fighter Squadron, an A-10 Warthog unit, as well as Apaches from the Idaho Air National Guard, are located at nearby Boise International Airport. According to the USAF report, they don’t appear to be part of this training, which is surprising. One can only imagine that this would change if the exercises continue as intended. Also, Mountain Home AFB plays host to a number of visiting combat aircraft detachments each year, including those from allies aboard that come to the base for the open airspace and nearby ranges.

The lawsuit states that there are a number of potential hazards presented by the training and says the USAF didn’t do enough to give local communities a heads up about the exercises and to take their input into consideration. The Idaho Press notes that an official Air Force assessment concluded the missions would cause no environmental impact of significance and that a 30-day period in which stakeholders could review the project was part of the plan. Seven meetings with residents of local communities where the training would mainly take place were also held. Still, the suit argues this was too little as not every community that would be impacted was offered a meeting, the 30-day feedback period, or even a formal notice of what would be going on, as just a webpage on Mountain Home AFB’s website explained the plans.

The Idaho Press writes:

As of Wednesday, the U.S. Air Force has not filed a response in the case, which originated in the U.S. District Court of Idaho, due to the fact that it involves the federal government. An official with the Mountain Home Air Force Base did not return a call seeking comment from the Idaho Press by late Wednesday afternoon.

The complaint alleges the Air Force began “conducting project training operations over the urban centers” before the review process was complete, indicating that it had made up its mind beforehand, attorneys wrote in the complaint.

We will have to see how all this plays out as it may impact similar potential arrangements in other locales across the United States, especially as the USAF continue to put a greater priority on this type of training. News of this type of exercise is also sure to fire up the conspiracy theorists who look at any urban warfare training as some sort of prelude to the government declaring Martial Law.

We will let you know how the USAF responds to the suit when those details come available.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com