A newly declassified document shows that, during the Cold War, the U.S. military considered turning Lockheed’s D-21 Tagboard supersonic spy drone into an unmanned strike platform. The plan would have given the U.S. Air Force a high-speed, deep-penetrating, air-launched strike weapon and it’s a capability the service is still interested in acquiring today.

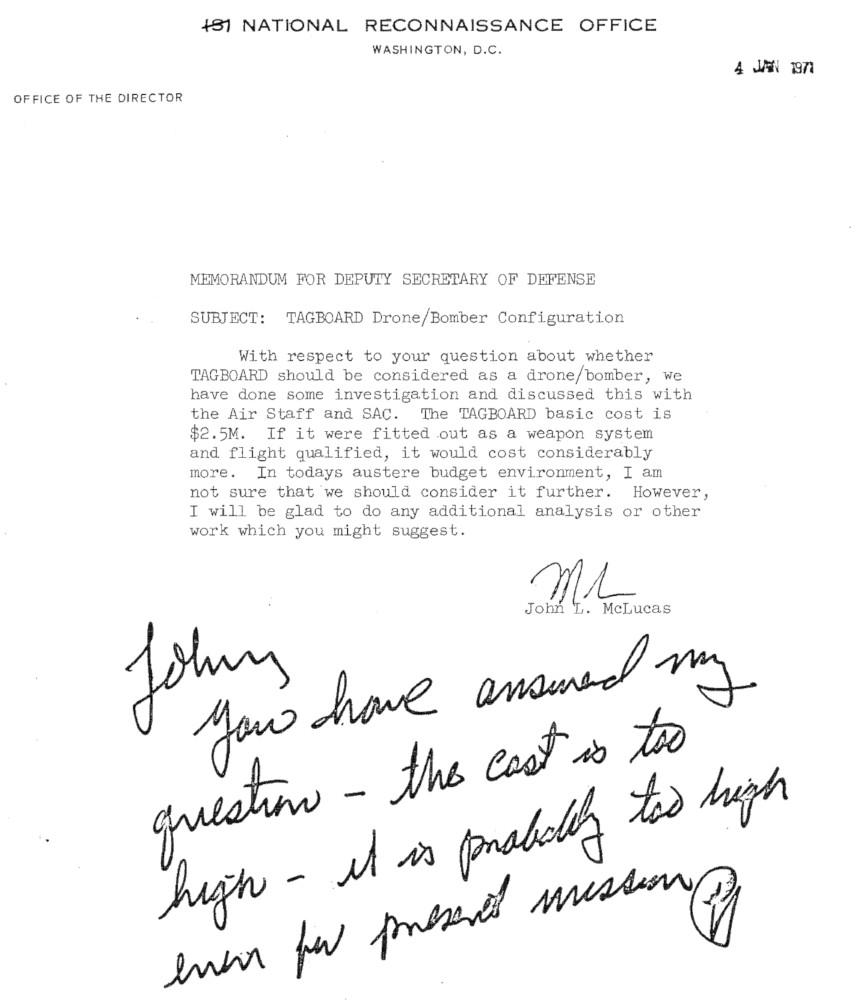

In January 1971, John McLucas, then both Undersecretary of the Air Force and Director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), sent a memo to Deputy Defense Secretary David Packard about the armed D-21 proposal. NRO, the very existence of which remained classified until 1992, released this record and nearly 100 other documents related to the Tagboard program as part of its continued transparency efforts, on Mar. 21, 2019.

“With respect to your question about whether TAGBOARD should be considered as a drone/bomber, we have done some investigation and discussed this with the Air Staff and SAC [Strategic Air Command],” McLucas wrote. “I will be glad to do any additional analysis or other work which you might suggest.”

But Tagboard’s origins, and nearly two decades of development and operational activities up to that point, were rooted almost exclusively in intelligence collection. To rewind a bit, after the Soviet Union shot down Gary Powers flying a U-2 Dragon Lady spy plane over their territory in 1960, there was a considerable impetus to develop less vulnerable intelligence gathering assets that could penetrate far into denied areas with limited risk.

Lockheed, which had designed and built the U-2, was already in the process of developing a successor, known as the A-12 Oxcart at the time. This aircraft subsequently evolved into the Air Force’s famous SR-71 Blackbird.

The A-12 could fly at over three times the speed of sound at around 90,000 feet, but there were still reservations within the U.S. government about sending any manned aircraft on high-risk missions over hostile countries, such as the Soviet Union. At the same time, NRO was pushing ahead with the first generations of spy satellites, which, at the time, offered a way to spy on these areas with virtual impunity.

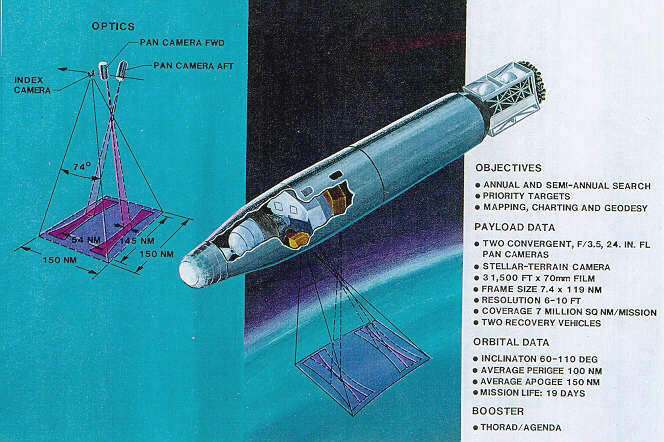

The problem with early spy satellites was that they could only carry limited amounts of wet film, reducing their capacity to cover large areas and do so over a protracted period of time. In addition, they had limited repositioning flexibility once they entered their orbits. On top of all this, it was a complex process to prepare additional satellites for launch, making it difficult to ensure one was ready to go on short notice in response to new developments.

So, the U.S. government had sought out additional alternative intelligence gathering platforms that were less vulnerable than manned aircraft, but more flexible than a satellite. The Central Intelligence Agency, which controlled the A-12 fleet, approached Lockheed and its Skunk Works advanced projects division in 1962 to ask for new options.

One concept that Skunk Works proposed envisioned using a modified A-12 as a mothership to carry and launch a rocket booster with a small satellite on top into low orbit. You can read more about this project here.

Another idea involved a modified A-12 as a launch platform for an air-breathing, high-altitude supersonic unmanned spy drone. CIA passed on this proposal, but NRO picked it up, ultimately giving the project the codename Tagboard. At that time, there were no plans to turn the unmanned aircraft into a strike platform.

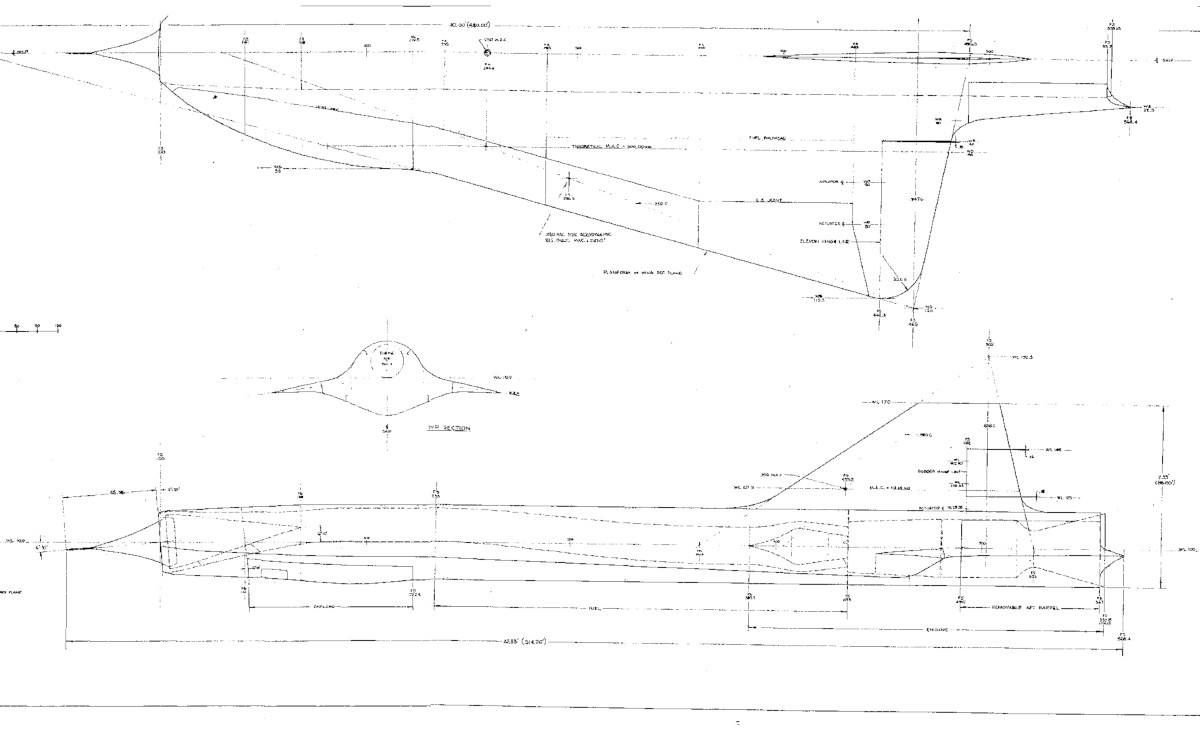

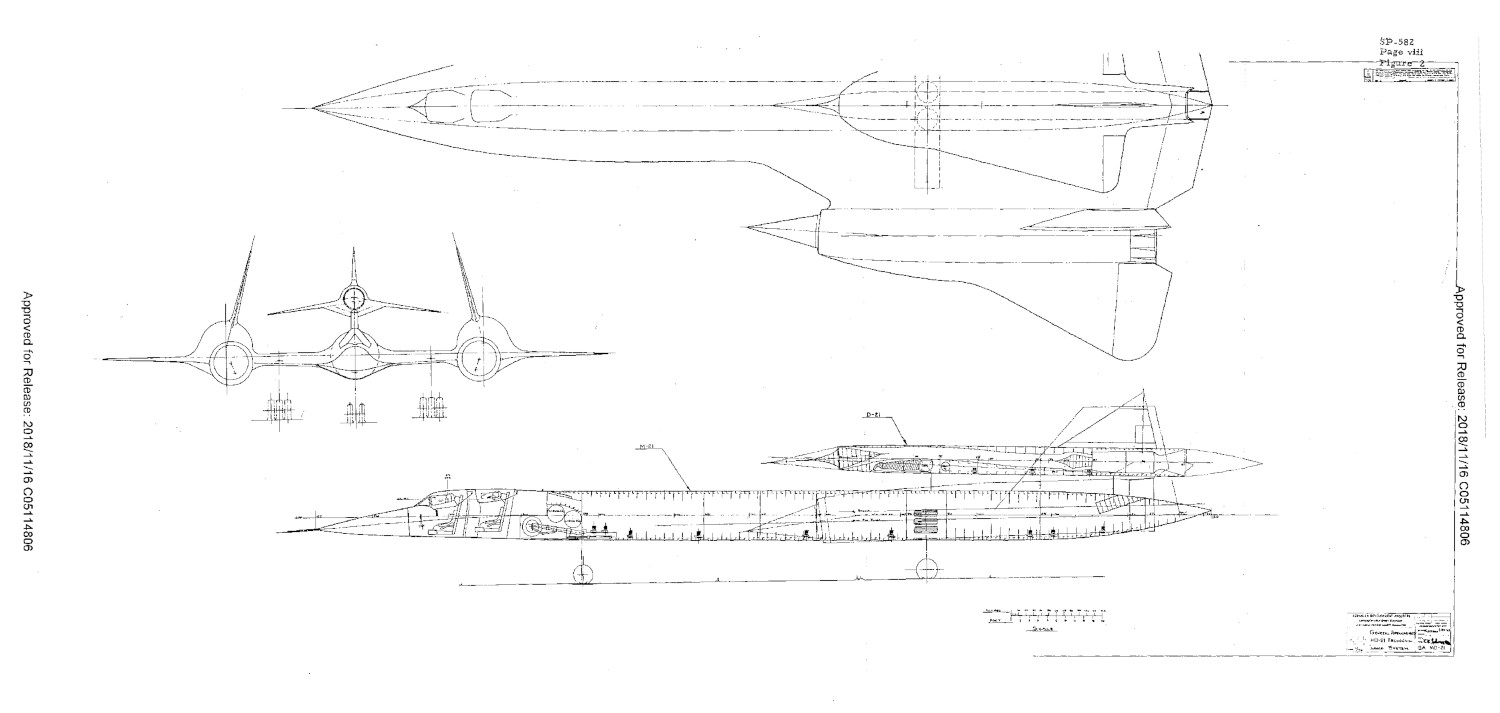

The delta-wing unmanned aircraft, constructed primarily of titanium, was more than 40 feet long and had a wingspan of 20 feet. A modified Marquardt RJ43 ramjet engine, also found on the CIM-10 Bomarc surface-to-air missile and AQM-60 Kingfisher target drone, could propel the D-21 to speeds over Mach 3 at altitudes of around 100,000 feet – higher than the A-12’s service ceiling.

Tagboard needed its modified two-seat A-12 motherships, which became known as M-21s, to get it to sufficiently high speed for the ramjet to operate efficiently. After release from the M-21, the drone would fly a pre-programmed route totaling more than 3,000 miles using an automated stellar navigation system, something you can read about more here. The drone carried a single Hycon HR 335 camera that could capture images of areas up to between 14 and 16 miles wide, depending on altitude, as it screamed across enemy territory.

After conducting its mission, its route would take it back out to neutral territory, where it would eject the film canister, which would then deploy a parachute. The D-21 was not reusable and was configured to self-destruct after releasing its payload.

A specially modified JC-130 Hercules cargo aircraft would snatch the film out of the air using a complex trapeze before reeling it in inside and transporting it back to base for processing. The Air Force, with the help the CIA and NRO, had devised this concept first in the 1950s to catch falling film pods that spy satellites released. This continued to be the standard practice for retrieving film and other data from satellites until technology had advanced to the point where it was practical to transmit imagery and other information wirelessly straight to a ground station.

Given Tagboard’s general performance characteristics and other features, it’s not hard to see how Strategic Air Command would have looked at the drone and seen a very viable weapons platform, and one that could help it maintain relevant in the age of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM). If Tagboard could carry a camera and film along a specific route before releasing a film canister at a precise moment, it certainly could have carried a nuclear bomb and dropped it over a designated target area.

By the late 1950s, it was already apparent to that American strategic bombers, the B-52 in particular, would be extremely vulnerable to Soviet air defenses and combat aircraft during an all-out conflict. As a result, the Air Force had already initiated work on an air-launched nuclear-tipped ballistic missile, GAM-87 Skybolt, and a long-range nuclear-armed cruise missile, the GAM-77 Hound Dog, as stand-off options for the B-52.

The Hound Dog, which was supposed to be an interim weapon until the Skybolt was ready, had a maximum range of 785 miles and a top speed of just over Mach 2. The Skybolt could hit targets up to 1,150 miles away and, since it flew in a ballistic trajectory, would come screaming down on its targets at hypersonic speeds over Mach 12.

Skybolt suffered significant delays in testing and, in 1962, President John F. Kennedy canceled the program in favor of a combination of submarine-launched Polaris ballistic missiles and land-based Minuteman ICBMs. Hound Dog, which had entered service in 1960, would remain operational until 1978.

An armed version of Tagboard would have offered more than three times the range of Skybolt and be able to cover that distance at an even greater top speed. Without the need for the drone to return to a safe area to deposit the film canister, it could have struck targets out to its full range of more than 3,000 miles – far enough to hit Moscow from a launch point in the middle of the North Atlantic.

Depending on the exact configuration of the weaponized drone, it could have possibly dropped multiple bombs at various points over a particular route. The Air Force could have simply employed it as more of a missile, carrying a single warhead straight to a target. A mix of both options might have allowed it to strike multiple objectives along the way to a final destination, where it would have detonated one last warhead.

In addition, just as Tagboard was more flexible than launching spy satellites, a “bomber” version of the drone, which was how NRO Director McLucas described it to Deputy Defense Secretary David Packard, would have offered many of those same advantages over IBCMs. The unmanned aircraft’s high speed could have made it useful for striking time-sensitive targets at shorter ranges, as well.

The launching aircraft would have retained all of the benefits a bomber brings to the table, too. These include the ability to fly on alert closer to the target area during a crisis, offering a visible deterrent whether it launches its payload or not. Bombers are also easier to recall than a ballistic missile, able to fly right to the edge of enemy air space before having to release an actual weapon, giving commanders more time to respond to new developments and potentially abort the mission. All of this remains the case today and are among the main arguments for keeping the B-52H in service through 2050.

Unfortunately, Tagboard and its M-21 motherships quickly proved to be complex and finicky. The physical interactions between the M-21 and the D-21, which the manned aircraft carried on top of its fuselage, were downright dangerous.

In the first test flight of the M-21/D-21 combination on Mar. 5, 1966, the drone remained worryingly close to the mothership aircraft after release before flying away safely. The next two tests involved uneventful separations, even though the drone malfunctioned later in its flight in both cases.

The fourth test on July 30, 1966 came to a tragic end when the D-21 suffered an engine problem during release, struck the tail end of the M-21 as it fell away, and destroyed both aircraft in the process. Pilot Bill Park and Launch Control Officer Ray Torrick ejected as their plane went crashing into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California. Park survived, but Torrick unfortunately drowned.

Lockheed Skunk Works’ legendary boss Kelly Johnson was so distraught over the accident, he initially refused to work on the program any further and offered to refund the money the U.S. government had already paid. However, NRO and others insisted on continuing the program, so Johnson offered to mate the D-21 to an alternative launch platform, a B-52H bomber.

The resulting configuration consisted of a B-52H fitted with two heavy pylons, on under each wing, similar to the ones the bombers used to carry Hound Dog missiles, but each carrying a single D-21 instead. Since the lumbering bombers couldn’t reach supersonic speeds themselves, Lockheed modified the drones to incorporate a rocket booster to propel them before the ramjet could take over. These new D-21Bs also had a command self-destruct feature, in case of a serious malfunction.

The Air Force stood up the 4200th Support Squadron at Area 51 to support the initial test program, which involved six test flights, between January and June 1968, nicknamed Captain Hook I through VI, according to a now declassified history of the unit that NRO released. On Nov. 9, 1969, a B-52H flying from Andersen Air Force Base on Guam launched the first operational D-21B mission, which sent the drone flying over China’s Lop Nor nuclear test site, as part of Project Senior Bowl.

That drone never returned, reportedly flying on into the Soviet Union and crashing. In February 1970, the 4200th conducted another test flight, nicknamed Long Drive, on the Pacific Missile Range off Hawaii to validate a number of fixes.

After that, there were three more Senior Bowl missions over China. Of the two that actually returned as planned, both experienced issues with releasing the film canisters, which were subsequently lost. On the final operational flight, on Mar. 20, 1971, the drone crashed inside China. The remnants are now on display in that country.

By January 1971, when NRO Director McLucas responded to Deputy Defense Secretary Packard’s inquiry, there was clearly a growing disappointment with Tagboard, as well as its cost. In his memo, McLucas noted that each Tagboard drone, of which there around 20 at the time, had cost $2.5 million – more than $15 million in today’s dollars, but still cheaper than the cost of the latest iterations of the MQ-9 Reaper – and that he wasn’t sure exactly how much more it would take to convert them into a strike platform.

The exact cost of the program remains unclear, especially since it included funding from various black budgets, but reportedly would have been valued in the billions in present-day dollars. Regardless, Packard was clearly struck by these figures.

“Johnny, you have answered my question,” he hand-wrote on the memo in return. “This cost is too high – it is probably too high even for [its] present mission.”

The armed Tagboard drone never came to be. The Nixon Administration canceled the entire program in July 1971. The 17 remaining D-21s went into storage first at Norton Air Force Base in California and then at the boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, where they became visible to the public. The program remained officially classified until the 1980s.

Today, there are 12 D-21s on display, 11 in the United States and the one in China. The sole surviving M-21 mothership is in the Museum of Flight in Seattle Washington.

It’s important to note that even as the D-21 program was getting underway, the Air Force was already beginning to very seriously investigate radar-evading stealth technology. As those efforts progressed and general concept became more viable in the 1970s, stealth steadily replaced speed as the primary means of penetrating an enemy’s air defense network.

But the general concept behind the D-21 has lived on in many ways. In the 2000s, Skunk Works worked with the U.S. Navy to design an advanced supersonic cruise missile as part of the Revolutionary Approach To Time Critical Long Range Strike (RATTLRS) program.

The resulting BGM-178 missile was very reminiscent of the D-21. It featured a Rolls Royce YJ102R turbojet engine, a high-axial flow design that would have been able to propel the weapon, armed with a penetrating high explosive warhead or a payload of small submunition bomblets, to speeds around Mach 4. This means it could have reached its maximum range of more than 500 miles in around 30 minutes.

Similar to how an armed D-21 might have operated, the Navy envisioned RATTLRS as a sea-launched weapon that would have been able to penetrate deep into denied areas and do so quickly in order to be able to strike time-sensitive targets on short notice. This program disappeared from the public eye at the end of the 2000s before any flight tests occurred, but the missile’s development may have, at least, helped inform the development of a more advanced and top-secret supersonic weapon, known as Sea Dragon, which you can read about more here.

But whatever happened to RATTLRS, the demand for improved capabilities to allow the U.S. military to hit critical targets at extended ranges quickly hasn’t dissipated. Quite the opposite has happened and there has been an explosion of interest in hypersonic aircraft and missile designs as of late. Even the B-52 is being eyed again as the ideal vehicle to haul and launch outsized high-speed missiles, much like how it was used for the D-21 program.

At the same time, potential American opponents, especially Russia and China, have been hard at work developing improved radars and other sensors so that they can detect and possibly engage stealth aircraft. This has only further placed a renewed premium on speed, not just to be able to hit targets promptly, but in order to reduce the vulnerability of aircraft and missiles to enemy air defenses in the process.

So, while the D-21 never achieved success in the intelligence gathering role, and never transformed into a strike platform, it certainly helped blaze the trail for new developments that we may come to fruition in the near future.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com