A little less than three years ago, the Australian Army said it would evaluate an unusual backpack-mounted pole-and-sling combination called the Reaper that could make it easier for machine gunners and snipers to carry their weapons on patrol. Now, The War Zone have obtained trials reports that make it clear the Australians weren’t impressed and found the system to be far more of a burden than a benefit.

In December 2016, the Australian Army officially rejected the Reaper Small Arms Carriage System, or RSACS, and informed the manufacturer, Advanced Accuracy Solutions, of its decision. The Idaho-based company had first demonstrated their piece of kit at an Army Innovation Day showcase in October 2015.

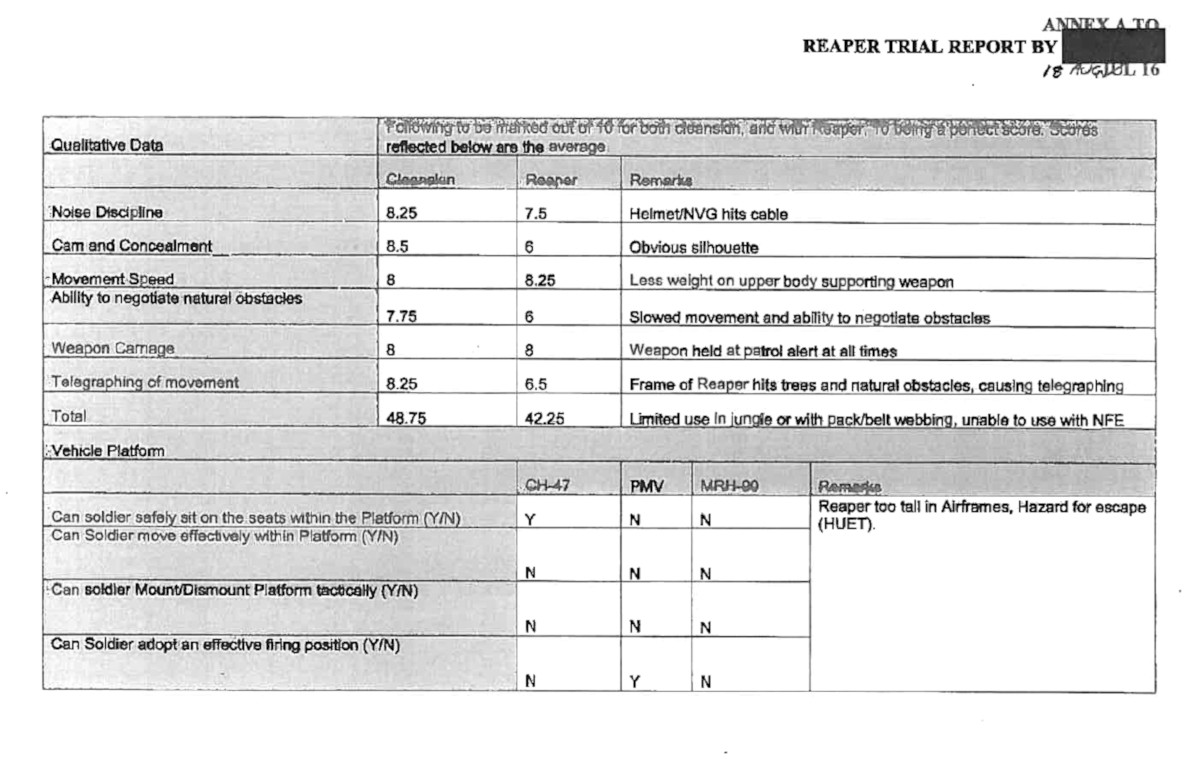

“The Australian Army units involved in the trial of ‘The Reaper’ all indicated that although it may have utility in specific situations, these advantages were outweighed by a number of disadvantages,” an unknown officer wrote in a letter to Advanced Accuracy Solutions. “These disadvantages included compromised camouflage and concealment, integration with night fighting equipment and user safety in airframe and vehicle platforms.”

The War Zone obtained this partially redacted document and other records related to the Reaper trails via Australia’s Freedom of Information (FOI) law.

Reaper consists of a two-piece aluminum pole attached to a frame a shooter wears like a backpack. This assembly extends up over the user’s shoulder. A cord extends from the curved end of the pole and attaches to their gun.

The basic idea is that this arrangement offers additional stability to improve accuracy and reduce the physical strain of carrying a rifle or machine-gun around at the ready for hours on end. “Personnel patrolling for long periods of time can become combat ineffective, or at the very least have a diminished response to a threat,” Advanced Accuracy Solutions’ Jason Semple told me in an Email when I initially reported on the Australian Army’s trial in 2016.

He wasn’t wrong. Soldiers in any major military today are increasingly burdened with all sorts of weapons and equipment, especially if they’re conducting extended dismounted patrols. Machine guns and large sniper and anti-materiel rifles, which can weigh more than 20 pounds on their own, only add to the strain on soldiers assigned to carry those types of weapons.

“It’s a funny-looking contraption,” Australian Army warrant officer Nicolas Crosbie, who took part in the trials, said in an official video. “I’m interested to see … when we trial it with the soldiers, what they think of it and that sort of thing.”

The Australian Army trialed the system in combination with three machine guns, its version of the FN Minimi, known as the F89, the 7.62mm FN Maximi, similar to the U.S. Mk 48, and the FN MAG-58. Snipers also tested it together with their KAC Mk 11, Accuracy International SR-98, Blaser Tactical, and Accuracy International AW50 rifles. The evaluations also involved using various Reaper and weapon combinations together with the Bushmaster wheeled armored vehicle, the M113AS4 tracked armored vehicle, and the CH-47 Chinook and MRH-90 helicopters.

The response from soldiers was not positive.

“The Reaper trial sought to prove or disprove the hypothesis that the utilization of the Reaper by a Rifleman will provide greater lethality by reducing the effects of muscle fatigue and weapon instability in a mounted and dismounted role,” the final report concluded. “As a result of the evidence collected over the trial period, the hypothesis has been disproven.”

For one, the Reaper did reduce strain on a soldier’s arms when carrying a weapon. But it also increased fatigue from the awkwardness of firing and moving with the system on their back.

“The soldier’s breathing motion was exaggerated by the RSACS,” one report says. “This forced the soldier to tense his entire torso in order to effectively release each burst, thus significantly increasing the soldier’s overall fatigue.”

The change in high-mounted weight distribution also made it harder for troops to run and the pole made it impossible to get into a prone firing position. Advanced Accuracy Solutions has said that the Reaper can work when the shooter is prone, but the Australians vehemently disagreed in their trials. Troops also just found it difficult to put it on at all, usually requiring the aid of a second person.

These factors also contributed to a lack of any meaningful improvements in shooter accuracy. When troops firing their weapons unsupported while kneeling, they were able to achieve better effects without the Reaper at four of the six tested distances. The Australian Army said that the RSACS performed better during standing unsupported fire drills, but the improvements were still negligible.

Some of these results can certainly be blamed on a lack of experience with the Reaper and further practice using the system may have led to better performance. However, this would have meant the Australian Army might have been looking at increased training requirements had it adopted the system for widespread use.

In addition, ignoring the issues of accuracy and fatigue, the Reaper presented other serious problems. The pole made it difficult for soldiers to stay concealed on the open battlefield, maneuver through more constrained environments, such as buildings, and get in and out of aircraft and vehicles. The Australian Army determined that the system presented such a serious safety risk for personnel in helicopters, especially if they had to ditch over water, that it would preclude any soldier from wearing it during airmobile operations.

In an apparent attempt to be charitable, the Australian Army noted that the system could help soldiers stabilize heavy guns while standing in turrets on vehicles such as the Bushmaster wheeled armored vehicle. However, the report pointed out that these vehicles already had fixed mounts in those positions specifically for this purpose. In addition, Australia’s Bushmasters feature a remote weapons station that reduces the need for individuals inside to expose themselves to enemy fire at all during a firefight.

Advanced Accuracy Solutions says that the system can be folded away when users are riding in vehicles, something that is not mentioned in the Australian reports. However, this would mean that troops would have had to go through the motions of extending and collapsing the Reaper every time they mounted or dismounted a vehicle, which could have made the process more cumbersome, especially under fire.

Not surprisingly, the pole and cord also had a habit of getting caught on both foliage and other objects, as well as the user’s other gear. The system notably interfered with troops using helmets with night vision googles attached to them. It also made it difficult for machine guns with the F89 machine gun to open the top cover to reload or clear jams.

“The live fire trials identified that the Reaper, overall, created a decrease in accuracy and transferred muscle fatigue to the remainder of the torso,” the Australian Army concluded. “The Reaper is not suitable for dismounted operations. The Reaper for utilization in all mounted in all mobility platforms trialed.”

These potential issues had been obvious well before the Reaper trials began. But it’s not necessarily surprising that the Australians were still willing to consider the system.

Large armed forces, including the United States, have expended considerable time and resources to try and reduce the weight of things troops need to carry and mitigate the fatigue they experience lugging their individual loads around. This has included programs to develop everything from lightweight ammunition to powered exoskeletons.

Ammunition-filled backpacks, more commonly associated with action movies such as Predator, have been another option. “Third arm” systems such the Reaper, another Hollywood staple, most notably the M-56 Smart Gun in Aliens – a prop made from a Steadicam video camera stabilization system and an MG-42 machine gun – have offered the potential for a less risky and lower cost interim solution.

The U.S. Army is in the process of testing its own “third arm,” which clearly tries to mitigate many of the problems with the Reaper by placing the support under the shooter’s arm, rather than over the shoulder. It still remains to be seen whether the added bulk of this system offers more benefits than hindrances.

U.S. Special Operations Command recently put their “Iron Man” exoskeleton program, officially known as the Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit (TALOS), on ice, admitting that the initial prototypes had not met expectations. But SOCOM does intend to continue developing certain specific portions of the overall system that do show promise, including “a small arms stabilization system,” according to Task and Purpose.

So, while the Australian experience with the Reaper might have been poor, there’s still a possibility that troops in major militaries around the world might end up some similarly unusual contraption strapped to their backs in the future.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com