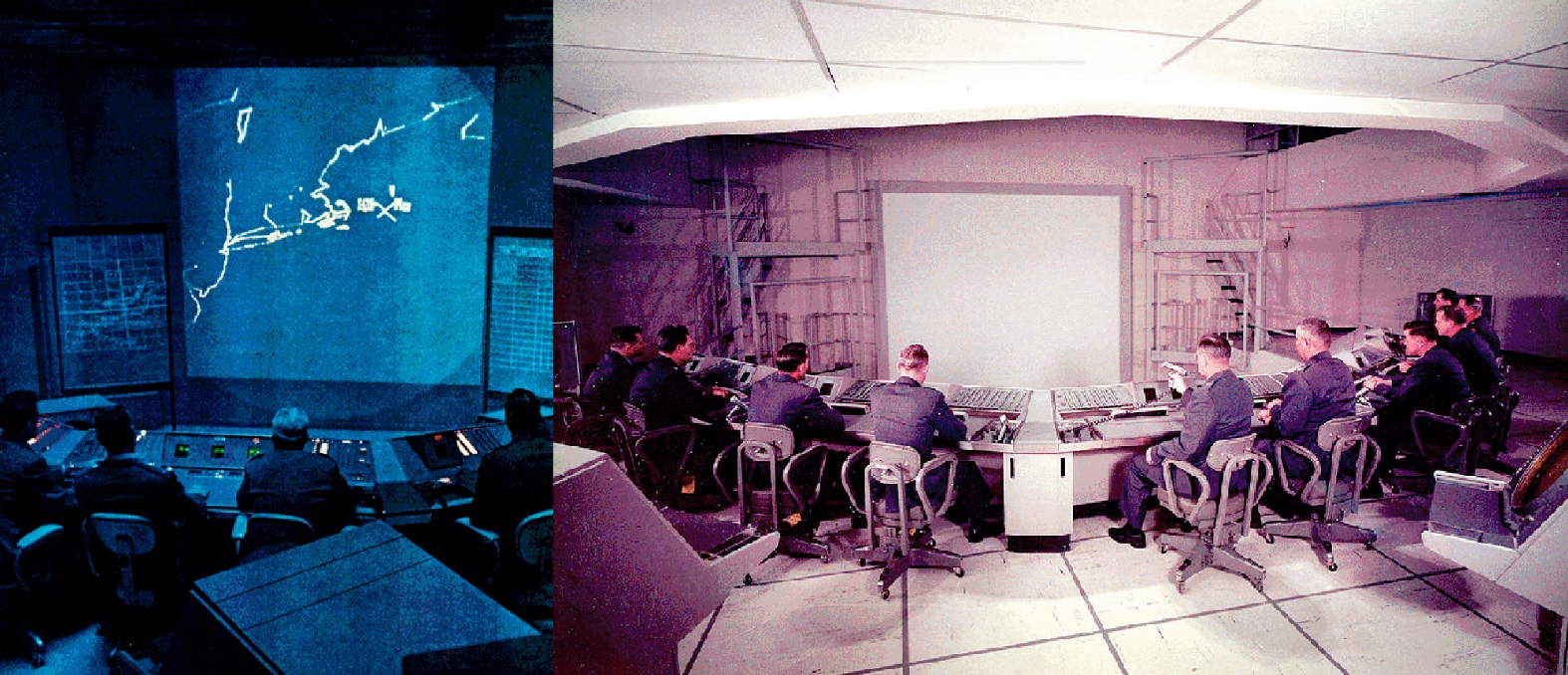

The photo above was taken at the height of the Cold War inside one of nearly two dozen Semi Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) Direction Centers that dotted the United States and Canada. The room seen here, nicknamed the Blue Room for obvious reasons, was one of many built inside the nuclear-fortified block houses that were really an elaborate and, at the time absolutely cutting-edge, weapon system in their own right. The oversized computer hardware, blinking lights and moody lighting, large projection systems, and austere bunker atmosphere influenced pop culture and science fiction heavily during SAGE’s heyday, which ran from 1959 through 1984.

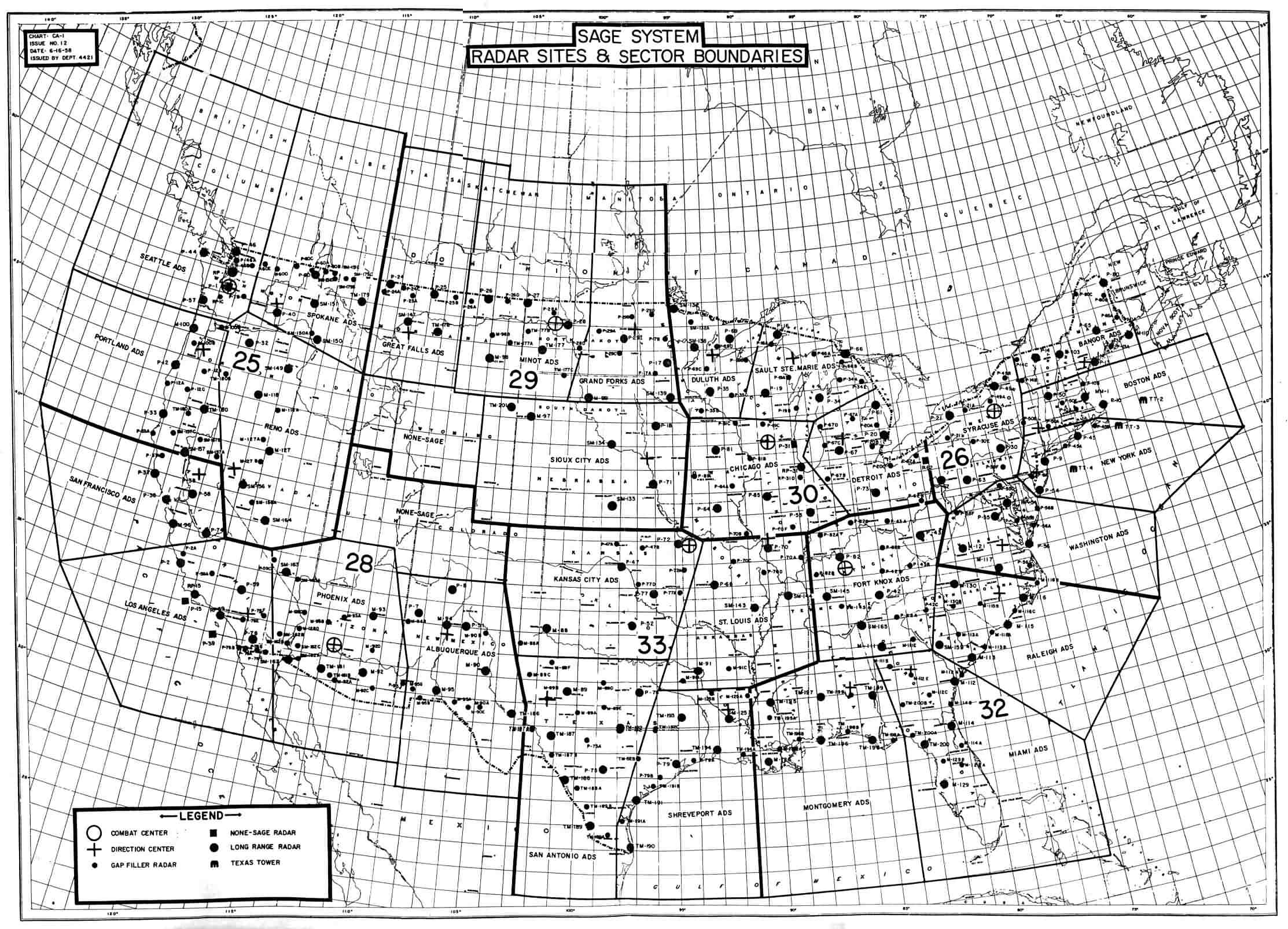

SAGE was the eyes and brains of North American Air Defense Command’s (NORAD) strategic mission having the job of detecting and directing the response to an incoming armada of nuclear bomb laden Soviet bombers. By default, it also kept tabs on air traffic around North America.

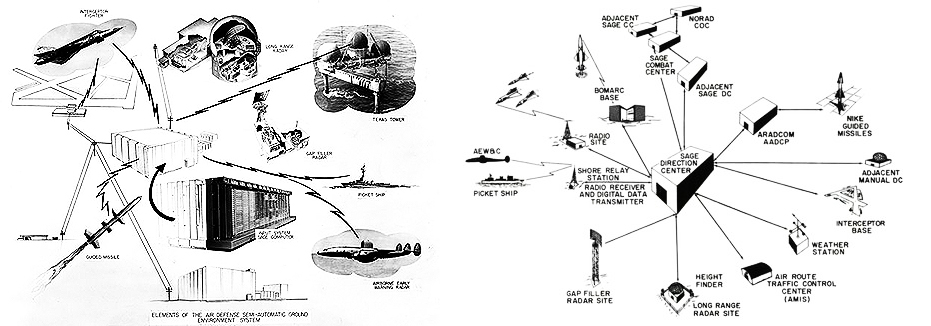

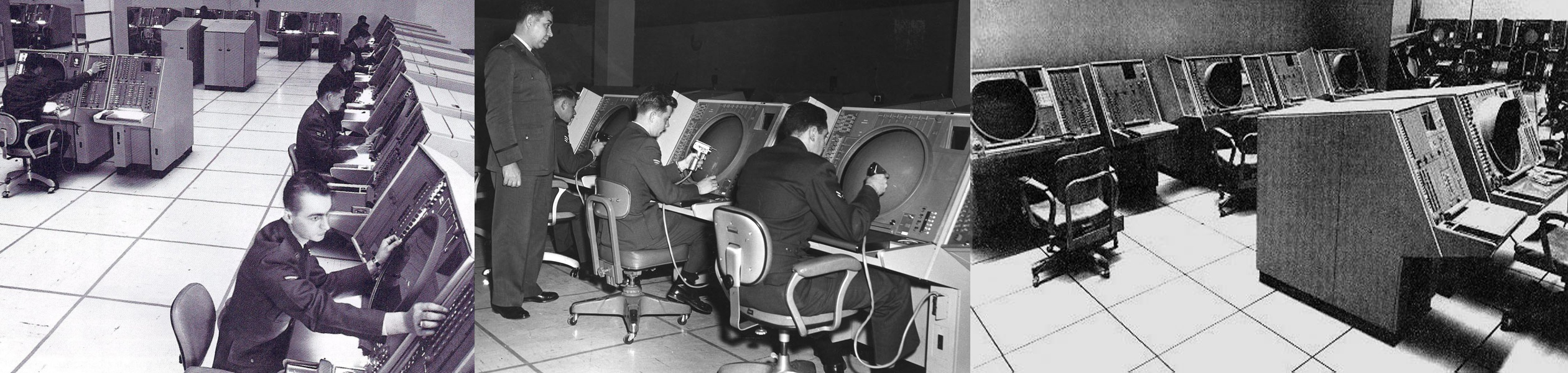

The system was amazing advanced for its time, running on huge mainframe computers that were interlinked to radar stations, radar picket ships, and airborne early warning aircraft, as well as surface-to-air missile and aircraft interceptor sites. Not long after its founding, SAGE gained the ability to remotely take control of surface-to-air missiles and interceptor aircraft, some of them nuclear armed, to prosecute incoming targets largely on its own. But it still was 1950s computer technology that ran on constant streams of punch cards and outputted teletype instructions. As such, even though it was highly automated for its age, it was also extremely labor intensive.

The system was also tied into a handful of master Combat Centers that could unilaterally direct North America’s entire air defense system during a conflict, as well as the Pentagon’s own nerve center, and NORAD headquarters. So, we are really talking about one of the first fully integrated data networks that spanned thousands of miles, as well as the dawn of what we know now as sensor fusion and an integrated air defense system (IADS).

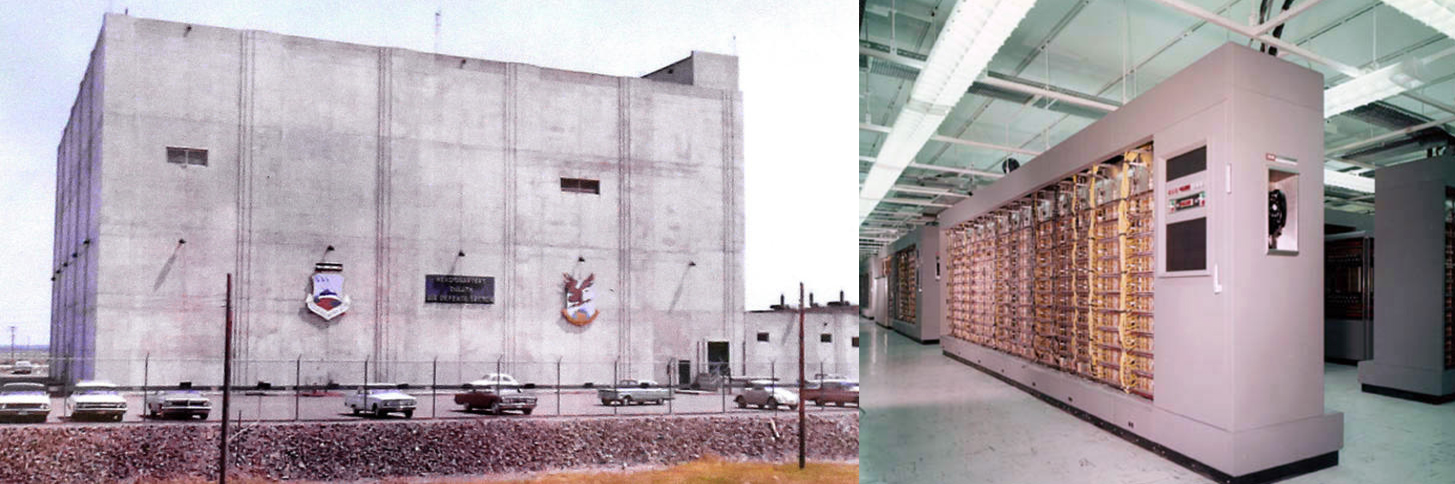

At the heart of each SAGE Direction Center was an enormous IBM AN/FSQ-7 duplex computer, taking up a whole level of the bunker structure—roughly 22,000 square feet—and made up of a whopping 49,000 vacuum tubes. It is also still the largest single computer system ever built.

This computer fused all the radar and other telemetry data from disparate remote sensors together to create common, relatively accurate radar tracks of targets and would even recommend the best response to them if they were deemed hostile based on the nearest air defense assets, those assets’ real-time status, and their varying capabilities. The duplex arrangement meant that one of the computers was always double checking the primary one and would instantly take over full functionality if the lead computer had any sort of technical difficulties.

The Direction Center bunker installations were built to withstand the pressure from nearby thermonuclear warheads detonating and were hardened from the effects of electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) as they had to continue operating even though what could have potentially been the beginning of the end of human civilization. This was all part of a deterrent strategy that was one abstract aspect of the complex and hugely expensive SAGE system.

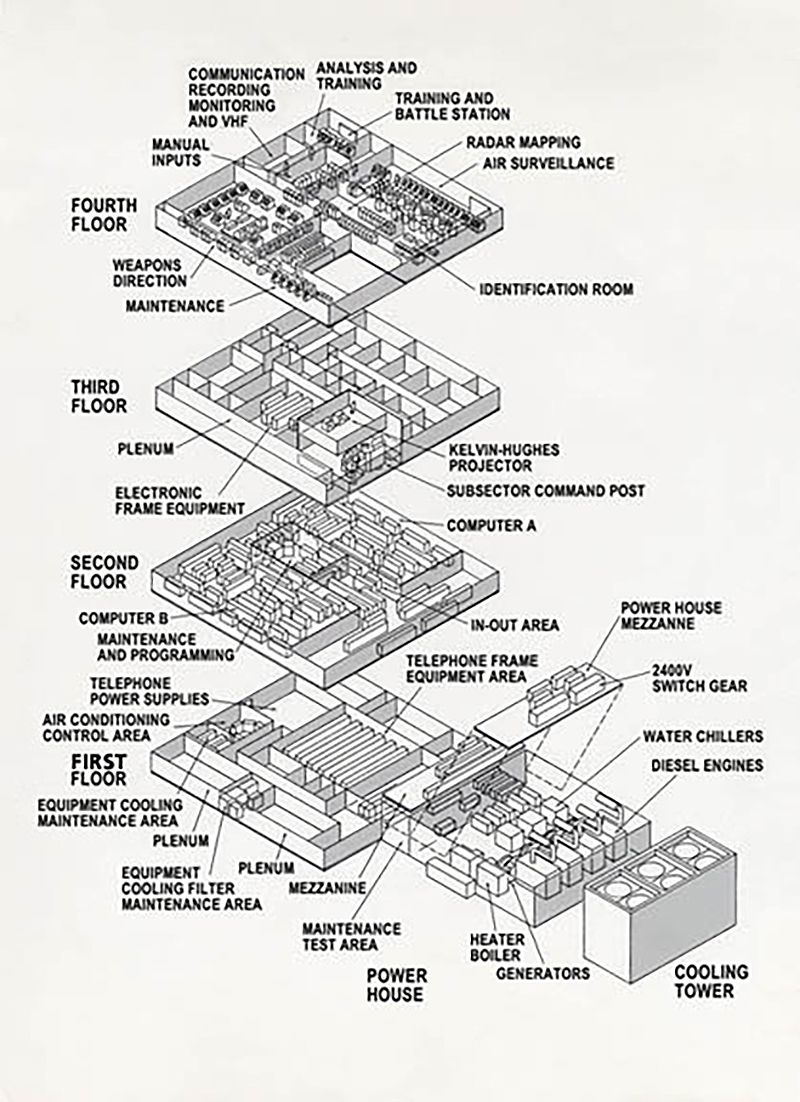

The foreboding-looking Direction Centers were high security, windowless, concrete and steel facilities made up of four floors. The first housing the mechanical and electrical systems and the heavy cooling systems needed to keep all that archaic computer technology running and the bunker’s inhabitants alive and communicating to the outside world. The second floor was where the massive AN/FSQ-7 was installed and maintained.

The third floor contained offices and store rooms, as well as the Sector Command Post. This was also a very sci-fi looking feature that inspired sets used in films and television shows for decades. It included a pit-like theater area where a large projection screen displayed a ‘big board’ that showed the air defense ‘picture’ over an entire geographical region. A cutting-edge Kelvin-Hughes projector was used for the big situational display.

Around the pit was seating for a command staff to oversee the status of the region at any given time and to make decisions based on the info fed into the projector, which itself was made up of ever-changing data being produced by the computer and a small army of radar operators housed on the level above, as well as a support staff that worked tirelessly to translate critical info into visual form.

The fourth floor is where the Blue Room photo was taken. Here is where all the information the computer fused was shown to radar and weapons control operators. Everything from threat discrimination and identification, to actually ordering or even controlling the employment of surface-to-air missiles and interceptor aircraft occurred on this level. It was from this information, much of which was filtered by the human operators, that those down in the Sector Command Post could make decisions.

Light pen technology, which was totally new at the time, and CRT monitors, were the technological backbone of the consoles used by SAGE operators. The light pens could designate/select targets to allow them to be classified and tracked.

Check out these awesome atomic age videos explaining SAGE and its incredibly complex functionality.

SAGE, which did get critical upgrades throughout its lifetime, has been gone for 35 years, and it is far cry from the office-like settings we see Air Force air defense operators working at today. The abilities that NORAD has presently seem lightyears ahead of SAGE, especially when it comes to automation and the streamlining of user interfaces, let alone the amount of data available at what amounts to a desktop computer workstation. But knowing that makes SAGE all that more jaw dropping technologically speaking.

Despite all the computers, the system was run by people. Lots and lots of people, including civilian contractors, some of which were women. It was not glamorous or particularly engaging work by any means. Basically, you were trapped in a fortified prison all day with no natural light and surrounded by buzzing and blinking computer gear. Considering the very nature of its utility—to repel a Soviet nuclear strike—not a whole lot happened outside of exercises, issues with airliners, and enemy training sorties skimming the SAGE network’s sensor perimeter. But that was the point. SAGE’s existence was all about not having to realize its fullest combat potential.

In that way it worked marvelously.

So, here’s to all the Americans and Canadians who spent large parts of their lives keeping an eye on the skies over North America from their futuristic, computer-stuffed, concrete cubes.

Just another group of unsung heroes of the Cold War.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com