Russia’s Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute, also known by its Russian acronym TsAGI, says it is exploring concepts for a high-speed compound helicopter for rescue and light utility roles in the increasingly strategic Arctic region. The announcement also comes as the Kremlin is in the midst of a number of other projects to develop new fast-flying military rotorcraft, including gunships and transport types, which could also benefit from the institute’s new work.

TsAGI announced the new research and development effort in a press release on its official website on Mar. 11, 2019. The institute said that the primary reason it was working on the new high-speed helicopter design was to support expanding civilian infrastructure, including various new oil and gas projects, in the Arctic. There is also the distinct possibility that there will be increased demands for search and rescue and medical evacuation services in this region as commercial maritime traffic increases as the period where seasonal pack ice threatens ships becomes shorter due to global climate change.

Concept art of a notional high-speed helicopter that TsAGI released along with their statement shows an extremely aerodynamic design with a rigid rotorhead and what the institute says would be a small jet engine at the rear. This is a well-established general configuration for a compound helicopter, which has historically offered increased speed, range, and fuel efficiency over comparable conventional helicopters.

The aviation research institute says that its goal is to develop a medical helicopter that can be on scene within 20 minutes of getting a request for assistance. That same rotorcraft should be able to ferry a patient with a life-threatening injury to a hospital within two hours. It is well-understood that the faster first responders can get a serious injured person to an established medical facility, the less likely that individual is to die or suffer serious complications.

“If we are talking about the Arctic zone with a very low population density or areas of oil and gas extraction that are very remote from the coast, then we must take into account that the maximum range of a helicopter flight can be over 1000 km [kilometers; approximately 620 miles],” Andrey Smirnov, who heads up research in the field of air transport at TsAGI, said in the press release. “All this testifies to the fact that it is impossible to do without high-speed rotary-wing aircraft.”

Any high-speed rescue helicopter that meets this description and has the ability to take on various light utility roles, as well, could also been extremely important for Russia’s growing constellation of military facilities in and around the Arctic. In January 2019, the Kremlin said that it planned to step up major military air activities in the region, which is known for extreme weather, very low temperatures, and extended periods with little or no sunlight.

A dramatic crash of a Tu-22M3 Backfire bomber as it attempted to land in bad weather in January 2019 underscored many of the risks involved in flying above the Arctic Circle. Those same environmental factors would also limit the window available for a helicopter to be able to safely fly out to a remote base to deliver crucial supplies or make it back to a larger hospital with an injured individual, further highlighting the need for a high-speed, longer-range design.

But TsAGI’s work on this light high-speed rotorcraft will also likely inform the development of future larger military transport and attack helicopters for use in the Arctic and elsewhere. Since at least 2008, Russian government-owned helicopter companies, primarily Mil and Kamov, have been working on faster compound helicopters for a variety of missions.

The Kremlin has since grouped all of this work together under the umbrella of a program known variously as the Prospective High-Speed Helicopter or Prospective Speedy Helicopter, generally abbreviated PSV. The main goal of the PSV program is to develop a variety of new helicopter designs with top speeds between 220 and 250 miles per hour, significantly faster than existing types in Russian military service. This in many ways mirrors the U.S. military’s own search for new, high-speed rotorcraft as part of the Joint Multi-Role (JMR) and Future Vertical Lift (FVL) programs.

In December 2015, Mil flew its PSV testbed, derived from the Mi-24/35 Hind gunship, for the first time. Known as the Mi-24K, not to be confused with the Cold War-era Mi-24K, the helicopter featured a more streamlined design compared to earlier Hinds.

It has rotor blades with curved tips, allowing for higher speed and greater stability, and the same Klimov VK-2500 turboshaft engines found in the Mi-28 Havoc and Ka-50/52 Black Shark/Alligator family. Mil said it hoped these additions, along with improved avionics and flight systems, would give the testbed a top speed close to 250 miles per hour, more than 40 miles per hour faster than the latest Hinds. It would also give the chopper an improved climb rate.

Mil has since proposed a clean-sheet compound helicopter design, the Mil Mi-X1, using many of these same features, as well as a rigid rotor and ducted propeller at the rear. The company also said it could serve as the basis for an unmanned rotorcraft, called the MRVK. The Russian design’s general layout to the American Piasecki X-49A Speedhawk, a compound helicopter derived from the UH-60 Black Hawk.

Kamov has not yet flown a testbed, but it has shown a number of high-speed concepts since 2008. These include the sleek Ka-90, a futuristic hybrid design that would fold its rotorblades into a stowed position after takeoff to fly like a normal airplane, and the portlier Ka-92 compound transport helicopter.

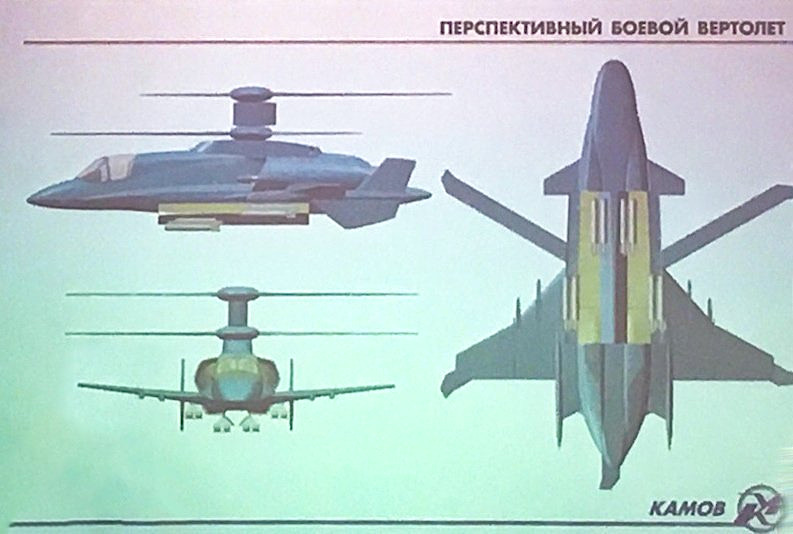

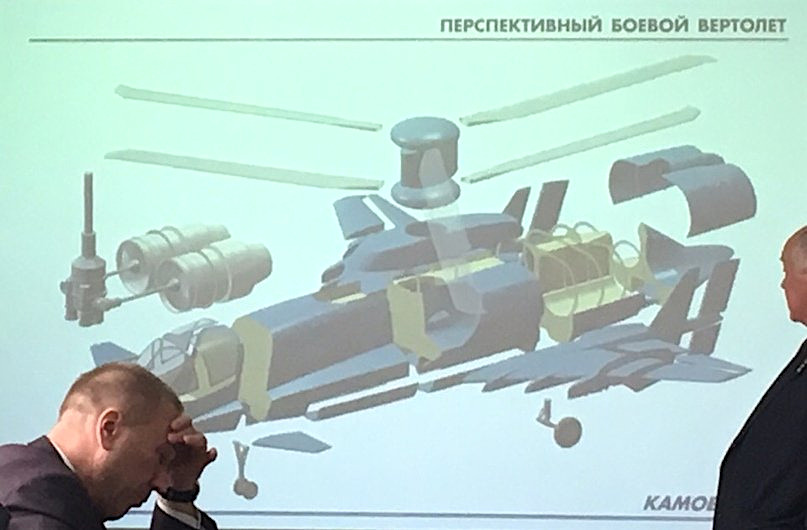

In late 2018, images emerged online of another Kamov concept for a compound high speed attack helicopter. The overall configuration featured more aircraft-like main fuselage with two large jet engines mounted at the rear together with a co-axial main rotor, along with internal weapons bays to help reduce drag. There was also a companion transport helicopter with a similar general layout.

An associated presentation reportedly claimed that the design might be able to reach speeds up to 435 miles per hour, dramatically faster than existing conventional helicopters. At present, the world record top speed for a non-jet augmented compound helicopter is just under 300 miles per hour.

TsAGI is already heavily involved with both the Mil and Kamov projects. In November 2018, the institute announced that it had developed further improved rotor blades for Mil as part of its PSV work. That same month, it announced it would collaborate with Kamov to develop its own high-speed testbed based on the Ka-52 helicopter.

Still, it remains to be seen how far any of the more ambitious projects, especially Kamov’s fighter jet-like rotorcraft concept, might progress. Russia’s overall defense budget has been contracting in recent years under the weight of a stagnant economy and international sanctions over the Kremlin’s involvement in conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, among others.

As of February 2018, the PSV program was still in Russia’s future defense plans. At the same time, the research and development work the project has been conducting could provide a path to more cost-effective upgrades to existing helicopters.

If new rotor blades and engines can offer major performance upgrades for helicopter such as the Mi-24/35 Hind, there simply may not be the same impetus to purchase all-new rotorocraft. Just in March 2019, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced it would move ahead with plans for a major upgrade of the Hinds to the Mi-35MV standard, which includes new engines, as well as upgrades to the helicopter’s sensor and targeting suite, additional armor, and the President-S directional infrared countermeasures system.

The Russian military is also slated to begin receiving new Mi-38T transport helicopters as a replacement for older Mi-8 and Mi-17 types in 2019. Again, these could be prime candidates for future upgrades based on developments from the PSV in lieu of adopting yet another new rotorcraft type.

The Kremlin could also look into compound conversions of existing helicopter types, based on design work TsAGI and others have done, as an easier and cheaper alternative to a clean-sheet design. Boeing is similarly developing a compound derivative of the AH-64 Apache gunship for existing customers, such as the U.S. Army, which promises a top speed of more than 250 miles per hour and significant improvements in range and fuel economy.

Squeezing additional speed out of existing helicopter designs still doesn’t truly meet Russia’s established requirements for long-range, high-speed helicopters, especially to perform critical missions in the Arctic. At the same time, despite budgetary constraints, the Kremlin has rightly decided that this region is of immense strategic significance and it is using what resources it does have to bolster its force posture there. This could help drive the continued development of at least one high-speed design, especially one capable of performing multiple missions.

All told, TsAGI’s latest announcement shows that Russia has a clear demand for high-speed helicopters, in the Arctic region and elsewhere, and that interest in various compound helicopter concepts remains high. But at the end of the day, the cash-strapped Kremlin may still have to settle for a less extensive fleet of new, advanced rotorcraft.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com