Derek “Maestro” O’Malley was a young fighter pilot rising quickly in the ranks when he decided to make a particularly crass gag video. What came next was nothing he ever imagined. All that he had worked for was suddenly at stake. But the Air Force gave him another chance, one that he ran with and has since achieved incredible heights of success, becoming the wing commander of the prestigious 20th Fighter Wing based at Shaw Air Force Base. Then, just days ago, it was his turn to make a disciplinary decision just like his superiors had in regards to his mistake a decade and a half ago. This one would be far more publicized. Now Colonel O’Malley relieved the first female demonstration team leader the Air Force ever had, Captain Zoe Kotnik, after just two weeks on duty. His decision made international headlines and the details surrounding it are still shrouded in secrecy.

After the video he created years ago, which is infamous in the fighter pilot community, was published on this site in relation to the ongoing story about the dismissal of Zoe Kotnik, O’Malley made the decision to reach out to us to share his story publically for the first time. And an amazing and intimate one it is. It speaks to the failings in all of us and how it’s not necessarily how you fail, but how you redeem yourself and use your experiences, no matter how unpleasant, to become a better person and a more thoughtful leader.

Judging by his responses alone, we need more people like O’Malley in the top echelons of the USAF’s leadership, ones who have learned to see the potential in people even when it is highly inconvenient to do so. For a force that is struggling to retain personnel, including pilots and maintainers—those who are absolutely critical to its core mission—giving people a second shot when it is possible to do so is really a necessity not a luxury.

So, without further ado, here is my remarkable interview with the colorful commander of the 20th Fighter Wing:

Can you tell us the entire story of how this video came about?

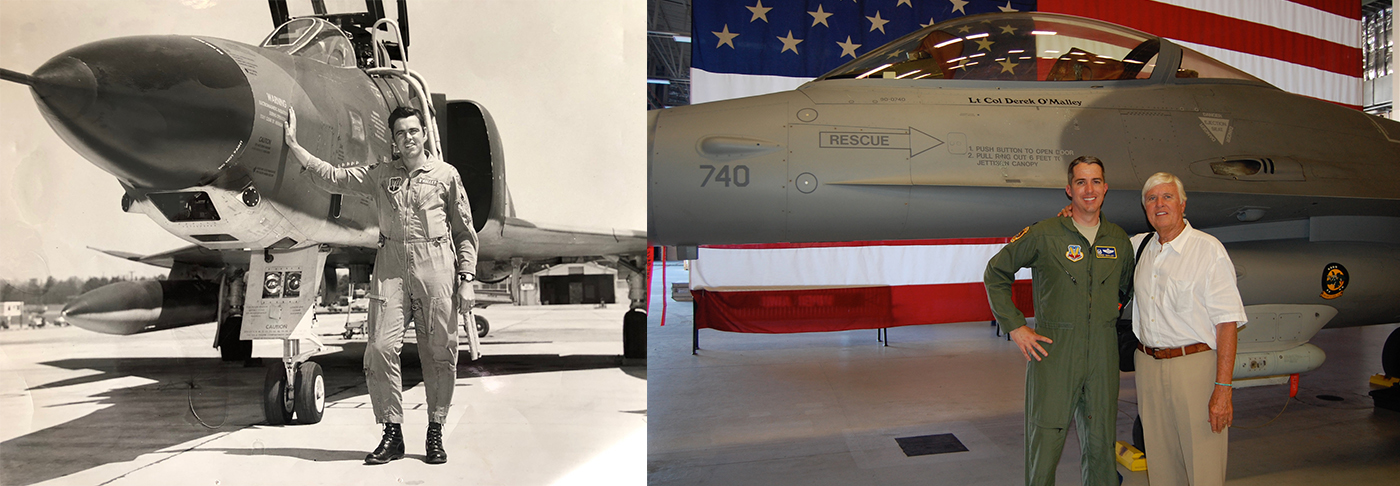

I’ll start early just to give you context. I have an identical twin brother. His name is Colin O’Malley and he and I are very right-brained, creative people, we’ve got a very active sense of humor. In high school, I was the student body president, he was the vice president and we had our own “Colin and Derek O’Show” and we would do funny videos, so comedic videos and having a sense of humor, is something that’s been a big part of our lives. My brother is a professional composer and musician, he’s actually an orchestrator, Yanni’s primary orchestrator… He does a lot of work for Disney and television, so he’s very successful. He writes a lot of jingles as well

With that background, I am now many years later, a young fighter pilot, a young captain in Kunsan Air Base, Korea. That’s a one-year remote assignment, so you’re there without your family in a very remote location. It’s a lot of fun, but it’s a very different environment.

In Korea, of course, it’s very humid and it’s a very high operations tempo, so we’re flying a lot. There’s a lot of big exercises as you’re practicing being in a high state of readiness in case something happens in Korea, and as we fly out over the Yellow Sea, we have to wear anti-exposure suits. And these are, you know, effectively dry suits. And they’re very hot.

When you’re flying you’re okay, but you can imagine wearing these in the hot summer in Korea? So, Gold Bond powder is a primary product.

One day I’m talking to some of my fellow fighter pilots and we’re joking about Gold Bond, I just started talking to them—”Hey we should do a little commercial.” As the Chief of Weapons and Tactics—I was the chief instructor in the squadron—I’m in charge of all the upgrades and making sure everybody is the best they can be, I’ve been through our equivalent of Topgun to the Air Force, the U.S. Air Force Weapons School. So, I’m in a very prominent role there in the squadron to lead these fighter pilots.

When your weapons officer says “Hey let’s make a commercial” everybody jumps says “Yeah that sounds like a great idea.” So, I told my brother about Gold Bond, and he came up with the jingle that you hear in the video, which is very catchy. And that’s him singing on there, so he composes that and sends it to me there in Korea, and I play it for everybody and it’s a big hit.

That morning, Saturday morning, I get everybody up and we’re there in our dorms, and we filmed the little commercial that you saw. In every fighter squadron on Fridays, you usually get together and you’ll tell stories about flying from the week. Mistakes people made, funny stories, those kinds of things, and then we’d show funny things like the Gold Bond video. I showed the video, it was a big hit, everybody laughed, and then that’s the end of it, it was not ever intended to go anywhere else of course.

This is pretty much pre-YouTube at that time right?

It is. I think YouTube was just emerging, but certainly, the notion of a viral video is not a term that any of us had heard yet. This is late 2004 timeframe. Eventually, this video gets in the hand of our rival squadron and they start sending it to each other. And then it gets emailed all across the base and then very quickly gets emailed all across the Air Force, and quickly spreads. You know, it becomes truly a viral video.

I was actually traveling home, it was around December time frame, going home for Christmas. You get a mid-tour when you’re there in Korea to go home, and as I’m walking through the airport somewhere in the United States, I see on somebody’s laptop the video playing.

And I remember looking at the guy I was traveling with saying “Uh-oh, I think I might be in trouble.” Because we just had no idea that the video would go outside the squadron. And now here I am, across the world, and it’s on somebody’s laptop! So, at that point, I got the sense of how big of an issue this was.

Of course, you’ve seen it, it doesn’t represent the Air Force the way I want to represent the Air Force, it doesn’t represent me the way I want to represent myself. As they should have, the Air Force looked into it, they weren’t happy with the video, and I definitely got in some trouble. I won’t go specifically into the punishment that I received, but I definitely got in trouble, to the point where I had to work hard to recover.

I remember when I was called into the Wing Commander’s office, there to receive my punishment. I looked at him said “Sir I’m so sorry, this is totally my fault. Please don’t punish all the other guys that were in this. They followed their Weapons Officer into this, so please just let me take the brunt of it.” And for the most part, that’s what happened. I was grateful that they let me own that.

After my one-year assignment in Korea I’d been invited to go teach at our Weapons School, which is very prestigious—our F-16 Weapons School. Weapons School is the Air Force’s version of Topgun where you graduate you get the trophy and you get invited back as an instructor. That is what I had been given the opportunity to do. Once this video broke, the Air Force was considering changing my assignment and was really looking hard at what they were going to do with me. Fortunately, they ended up letting me go to Nellis, to the Weapons School to be an instructor.

When I got to Nellis, my Wing Commander pulled me aside and said “You know Maestro, if you work hard, you’re going to be able to redeem yourself from this. So, just put your nose to the ground and get to work and be the best instructor officer you can be, and we’re going to put all this behind you.” And I really appreciated that, and I took him at his word, and I worked really hard at the Weapons School, won many awards there as a top instructor, used a lot of my video skills for the forces of good—I did a lot of videos for the Air Force and for the Weapons School that to this day are still used there.

I just tried to really prove to the Air Force that this was not who I was and that I was willing to do what I had to do to make things right.

I remember during all this, I would get a lot of emails from people that were angry about the video and I didn’t blame them. I remember one, in particular, was from a commandant of cadets at an ROTC detachment at a college and he wrote me on my government email and said “If this is the Derek O’Malley that did this video, you just took us back 30 years. Please keep this junk off the internet, you’re really shaming the Air Force, shame on you.” That was an eye-opening email to me, so I wrote him back and I still have the email to this day. It’s something I read, and I remember when I shared this with my squadron at a commander’s call I read the letter to them. Not only what he had said, but my response to him.

I explained “I lead men and women in combat, I’m a Weapons Officer, I have a Distinguished Flying Cross, I’ve done all these things, and I should’ve known better. Maybe it is easier to dismiss me as an officership failure. And I don’t blame you if you do. Fortunately, the men and women I’ve led into combat, and now lead recognize that good people, even great people, make mistakes. Maybe that’s the best lesson for your cadets. Regardless of our intentions with this video, I take full responsibility.”

He wrote me back and thanked me and shared the message with his cadets. It’s been a memorable lesson for me. It’s shaped the way I handle command, and the way I handle Airmen that make mistakes under my command.

Next, I was selected to the F-35 initial cadre. At this point, I definitely was in a position where from an Air Force perspective I was on the road to full recovery and I had the opportunity to do wonderful things. I was flying the F-35 at Nellis and I was commanding an operational test squadron that was testing the F-35 along with other aircraft, and this was around the time when General Welsh [Air Force Chief Of Staff at the time] implemented what I’ll call a cultural revolution across the Air Force, but particularly in fighter pilot circles.

He pulled all the wing commanders together and said “It’s time to clean up the crudeness and some of the things that have been propagating across our culture. This isn’t the environment that we want.” He knew it wasn’t how we wanted to represent ourselves as the Air Force and he took the initiative to correct it.

I remember my Wing Commander talking to all the squadron commanders explaining “Hey, we need to straighten up, clean this stuff up in your squadrons, and get back to the professional environment that we need. Doesn’t mean we can’t have fun, but there are some lines that we just shouldn’t be crossing.”

I remember standing up in front of my squadron and telling them the changes that were happening, the things that we weren’t going to do anymore, and that we never should have been doing. And I shared with them this entire experience as I’m sharing it with you, because I wanted them to hear it from me, and then to know that these changes that General Welsh was rolling out, that I believed in them. That I knew that they were important and that I wasn’t just spouting the party line and then saying “Oh, wink wink, I’m the Gold Bond guy, we’re going to keep doing things the way we always did it on the side here.” I’ve done that same thing at every level of command and shared the same experience.

We all do things that are stupid sometimes, but in the business that we do here in the Air Force, we’ve got to have an environment where everybody feels safe. And I feel like anything that I did in the past, or that we all did without even realizing it, that made this environment feel unsafe, or a place where people didn’t want to work, was wrong. We’ve got to get away from that.

I’m grateful for the changes that I’ve seen across the Air Force in that respect.

When you talk to younger pilots under your command about your experience, you have a bunch of them there at Shaw AFB, what’s their reaction?

Just recently when I first took command, I sat down and did an all call with the pilots and officers and shared this story. This video, at least in the fighter pilot world, while I’m not happy about it, is well-known. There’s probably not an F-16 pilot in the Air Force that doesn’t know of that video and that I did it. So, when I became the Wing Commander, I thought it was important to discuss it with the pilots.

I shared it with them and it was a good opportunity to be real, to show them that I still have a sense of humor and that we can have fun and joke around and be human. But at the same time, we’ve got to remember that we should hold ourselves to a higher standard. I felt like that resonated. I’m not telling them to change who they are, I just want them to recognize that who we were before isn’t who we want to be anymore, we’re better than that now.

Are airmen being systematically trained to realize the pitfalls of this type of thing? Is there just a training video they see or are they actually hearing about stories like yours in context to the current environment that’s out there right now, especially in regards to social media?

The Air Force core values and the way we train people to conduct themselves would lead you towards “Hey let’s not post ridiculous stuff about ourselves on the internet.” And I think there are enough examples out there like mine that people know “I probably shouldn’t do that.” I also think our young officers are way smarter on social media than any of us are.

Hearing it from people that are just repeating a message is one thing, hearing it from someone like you has an entirely different impact. If I was a young airman, I’d listen to this and say “Hey this is where I want to be in ten years, and after hearing this, yeah I wouldn’t pick up the camera and do that.” Maybe there’s a greater opportunity here?

I agree, and when I share this story, it isn’t just about social media and how you communicate on those platforms. For me, it’s broader. It’s about recognizing that every one of us has done something we regret. And you can learn from it, you can move on. Don’t forget that you’re not defined by the mistakes you make unless you choose to let them define you.”

So, on second chances. This is your story and obviously there’s an issue that’s ongoing. In your letter that you published [about removing Zoe Kotnik from her command] I believe you said that you hope that the individual takes the best advantage of a second chance or something along those lines. Is that something that is your position or do you see that more of as an Air Force position?

I wrote every word of that, that was not a prepared statement that anybody gave me, it is absolutely how I feel and embodies the way I lead. That was right from the heart.

What goes into making a disciplinary decision? How does the process work?

For most issues on Shaw Air Force Base—the 20th Fighter Wing—I am what we call the ‘convening authority.’ So, I have jurisdiction on what happens. But the Air Force widely tries to push autonomy and decisions down to the lowest level possible.

For example, I have 18 squadrons in my wing and those squadron commanders handle their own disciplinary actions within the squadron. They don’t funnel that all to me. It’s only when we’re talking about more significant offenses, where maybe somebody might get discharged, those kinds of things, that it starts to come up to a higher level.

You have this experience in your past, yet look how far you’ve come. I’ve read your resume, it is filled with some of the most incredible flying positions the Air Force has to offer. Today you command thousands of people on one of the service’s most important bases. What advice can you give those that find themselves in a ‘Gold Bond’ like predicament now? Not just in regards to not doing something stupid, but after the fact, once a bad decision has already been made? What can they do to make the best out of a bad situation?

That’s a great question. I’ll just talk broadly instead of talking about specific situations, but I can think of several cases here since I’ve been a wing commander where I’ve had someone in my office because something didn’t go well for them. And of course, when you’re coming to the wing commander’s office and you’ve done something wrong, you’re fearful. They are worried about what’s going to happen.

One of my favorite memories here in the wing was a time where a young man came into my office who made some significant mistakes, and I suspect he thought that his career was over. I sat there and talked to him, I was very stern and I think he thought “Okay here we go.”

I paused for a second and I held up what was potentially a discharge letter, and I tore it up right in front of him and I said “You know what? I believe in you, and my Command Chief believes in you, and your Squadron Commander believes in you. I want you to go back down to your squadron, I want you to learn from this, I want you to put it behind you, and I want you to move on and be the best Airman that I’ve ever seen in this wing. Prove to us that we made the right decision.”

That’s the message, right? I think it’s so important to have a commander, and I hope my commanders embody this, it can’t just be me, where we see the best in people. So, even when people do things that are just bad sometimes, we look at them and we see through that and we see past it and we recognize that there is so much potential here that we need to harness. That is how I approach it.

From the Airmen’s point of view, as I interact with them, it’s important that they can see themselves in me. If I’m always perfectly articulate and don’t show any vulnerability, I think it makes me seem unreachable. Nobody can relate to that. I want them to see that we’re very much the same and that there is no reason they can’t be a wing commander or whatever else they want to become. So, I start there. I sit down with them. I call them by their first name. I ask them about their family, their interests, their goals.

Now getting directly to your question, I tell them I know what it feels like to think that you’ve disappointed everyone that believes in you and that you’ve destroyed your career. And the easiest thing to do right now is to give up. But we need leaders in our Air Force that know what it’s like to be in their shoes. We need leaders that can look beyond a mistake or a momentary lapse in judgment and see the hidden potential in our Airmen. That’s the kind of leader I want them to become, so I ask them if they’ll take the steps necessary to put their mistakes behind them and join me in the revolution. Some say this is a one mistake Air Force. Not on our watch!

Obviously, it’s not easy in the internet age where social media can keep circulating something that you find personally and professionally unpleasant. But you combated this for years, didn’t you?

I thought to myself “Once something is on the internet it never goes away.” People always say that and I thought “Is that really true?” I mean of course an EMP, that could wipe it out, but that’s not an option! So, I did some research on copyright and realized that I had grounds to have it copyrighted. In fact, even by making the video I already had the copyright of it. But just to make it official I filed a copyright, I have the certificate to this day, and for the past fourteen years, every month, maybe twice a month, I go through the internet and I do ‘Gold Bond cleanings.’ I find the video and I reach out with the DMCA notices and I have it taken down. This thing pops up probably every month, I’ll see at least one, and I just snipe it. I’ve spent hundreds of hours over the past 14 years suppressing this video!

And it’s funny because you’ll see commentary on the internet, maybe you did as you researched this story. People think the government is doing this and the Air Force is somehow involved in this big conspiracy to keep ‘Gold Bond’ off the internet. Little do they know it’s just little old me. I don’t do this because of my Air Force career, I received my punishment and I had the opportunity to recover. It’s never been about preserving my career, and I always knew eventually it could come out as it did this week, but I had a young son at the time, he’s 18 now, and I challenged myself thinking “I don’t want him to come across this.”

And I did, I kept it away from him, he didn’t see it until he turned 18 and I finally showed it to him. He actually didn’t think it was that funny. He was disappointed after all those years. I guess I overhyped it.

There is another video of me on the internet that ties to my twin brother. As you may know in the fighter pilot world we have callsigns, you get a nickname and it’s kind of who you are. My call sign is ‘Maestro.’ And that’s based on my twin brother being a Maestro… And that’s just another one that’s out there. I haven’t tried to suppress that one.

At this point, why even chase it anymore? Why not let people learn from it? You’re a man of very high stature, you’ve done amazing things in your life and are clearly a huge asset to the USAF. What’s there to hide from? It’s an inspiration to people who do make a mistake and look to come back from it to go on to incredible success.

Yeah, it does change things now. This is very different, this is the first time someone has publicly told the whole story. While I’m not proud of the video, I wouldn’t trade the lessons I learned from those experiences. I wouldn’t be the father, friend, Airman or leader I am today without them.

As I look at the video now, I am grateful that’s not who we are as an Air Force anymore. Still, young Captain O’Malley should have known better. I’m grateful that my leaders saw something in me that was worth saving and gave me a chance to reach my full potential. That’s exactly what I will do every single day I have the privilege of leading Airmen.

But you’re right this does change things. This may finally free me from my penance of monthly ‘Gold Bond cleanings.’

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com