The U.K. Ministry of Defense has revealed plans for a new Royal Air Force squadron that will operate a fleet of unmanned aircraft able to fly networked together as a swarm. Depending on how the program evolves, it might involve the fielding of a true unmanned combat air vehicle, or UCAV, or at least serve as a stepping stone to realizing such an operational capability.

U.K. Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson briefly mentioned the swarm project in a wide-ranging speech on the future of the country’s armed forces at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) think tank on Feb. 11, 2019. The drones were among the many programs the Ministry of Defense is paying for through a new, flexible “Transformation Fund,” which has the intended goal of helping speed up the development of new and advanced capabilities across the country’s armed forces as a whole.

“I have decided to use the Transformation Fund to develop swarm squadrons of network enabled drones capable of confusing and overwhelming enemy air defenses,” Williamson said in his remarks. “We expect to see these ready to be deployed by the end of this year.”

His stated schedule for when the drones might enter service has already caused some confusion. An official statement from the Ministry of Defense has contradicted this timeline, saying that the unmanned aircraft are still years away from being ready for actual missions.

“The RAF will form a new squadron with a new concept, able to deploy swarms of network-enabled drones,” a Ministry of Defense spokesperson told U.K. Defense Journal later on Feb. 11, 2019. “The details of who will build the drones, the tender process and the technology which will be employed, will be developed over the 3-year program.”

A “tender process” means that the United Kingdom plans to hold a competition to pick a winning design rather than issue a sole-source contract to one particular company. It is possible that Williamson was actually indicating that the final selection of a particular drone would occur before the end of 2019.

The Ministry of Defense could conceivably approve a more limited buy of unmanned aircraft that meet a minimum of basic requirements in order to help quickly stand up the new RAF squadron and begin the process of training personnel on their new mission ahead of the full tender process. Williamson’s might be using the Transformation Fund to support this initial effort and jumpstart the program.

Beyond the exact nature of the procurement process being unclear, neither Williamson nor the Ministry of Defense has given any further details about the desired size and configuration of the drones themselves. The Secretary of Defense’s comments about their primary mission being to defeat enemy air defenses does not necessarily offer any clear indications about the required capabilities.

Swarms by their very nature are inherently threatening to enemy air defenses, overwhelming sensors and their operators with too many targets to properly prioritize and with reaction times and coordinated assaults that are beyond the abilities of human aircrews. Drones equipped with electronic or cyberwarfare packages could further disrupt or confuse an opponent’s defensive networks.

The swarms could also act as decoys, emitting signals similar to larger aircraft and distracting the enemy from higher value threats. Armed with conventional munitions or directed energy weapons, these unmanned aircraft could destroy air defenses themselves, helping to clear a path for follow-on strikes by more conventional aircraft. Of course, drone swarms can perform missions unrelated to enemy air defenses, too, and have a host of other highly beneficial qualities, in general, which you can read about in more detail here.

The video below depicts the possible capabilities the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Gremlins drone swarms, which provides a good general overview of the concept of employment and utility of swarming unmanned aircraft, in general.

The plan to establish a full squadron to operate the aircraft does point to drones that are larger than various air- and ground-launched systems presently under development around the world, especially in the United States and China, and are reusable. This would suggest Williamson was not referring to smaller missile-like systems, such as the Miniature Air-Launched Decoy-X (MALD-X) that the U.S. Air Force and Navy are developing. It is possible he could have been describing a smaller, but recoverable system along the lines of the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has in the works under the Gremlins program.

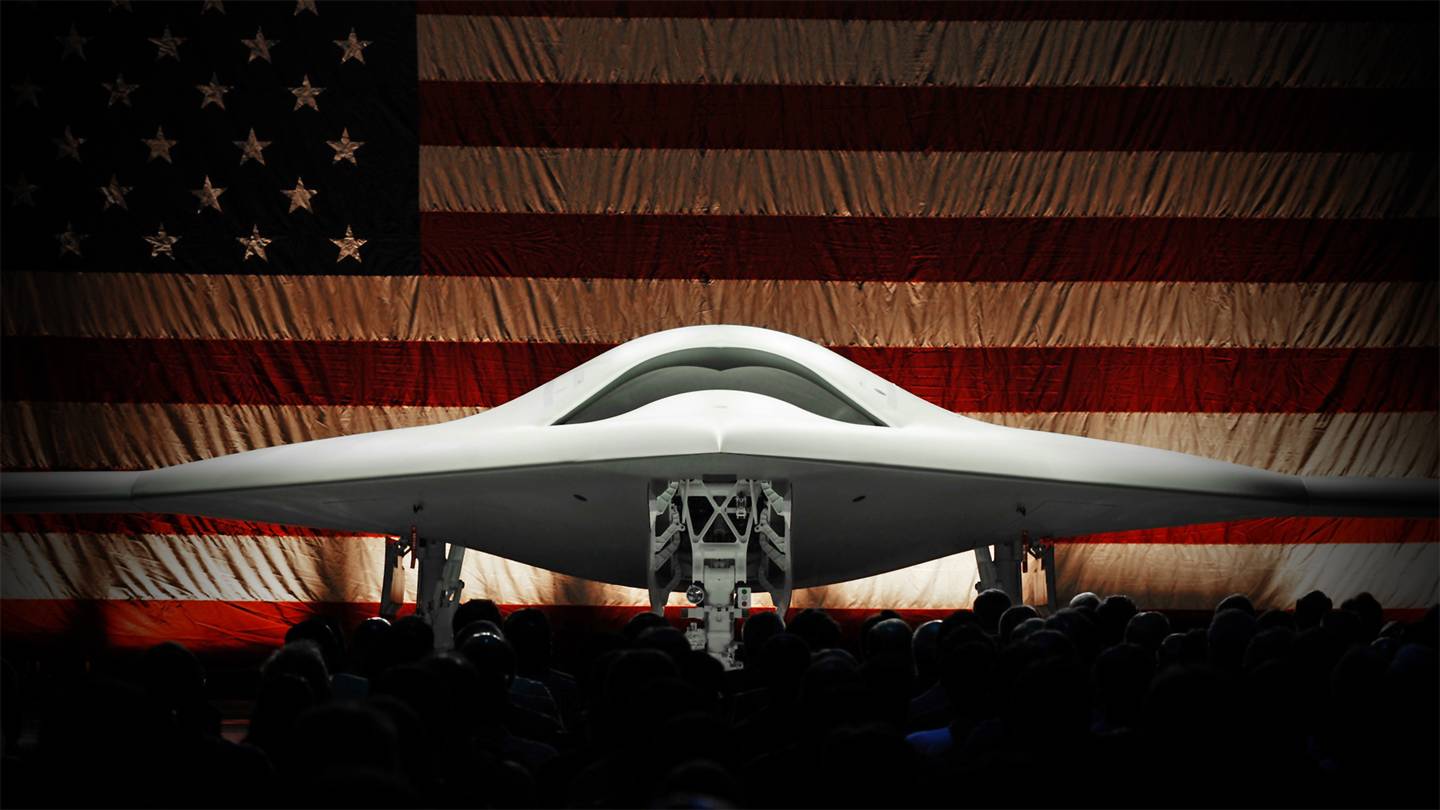

But from what we do know, it sounds more like the United Kingdom is interested in something more along the lines of the stealthy XQ-58 Valkyrie from American drone manufacturer Kratos. The U.S. Air Force is planning to test the XQ-58 as part of its own Low-Cost Attritable Strike Demonstration (LCASD) program and envisions the aircraft as operating in swarms and as “loyal wingmen” where they would fly networked together with manned aircraft.

The XQ-58, depicted in concept art as having aircraft-style tricycle landing gear, is an evolution of Kratos’ ground-launched XQ-222, also known as the Valkyrie. The company estimated that each XQ-222 would cost around $3 million, less than a quarter of the fly-away cost of the Air Force’s non-stealthy MQ-9 Reapers.

Despite its relatively low price tag, this earlier design could carry a pair of 250-pound class GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bombs, electronic warfare systems, sensors, and more. When the firm unveiled this earlier Valkyrie design in 2017, it said that the unmanned aircraft would have a maximum range of more than 3,000 miles and a combat radius of up to 1,500 miles, depending on the payloads inside. Jane’s subsequently reported that the maximum distance the drone could fly was closer to 2,100 miles. For some context, a straight shot from London to Moscow is around 1,500 miles and fighter aircraft generally have a combat range of around 700 to 1,100 miles.

The XQ-222 itself was an outgrowth of Kratos’ previous work with the Unmanned Tactical Aerial Platform-22 (UTAP-22), also known as the Mako. The ground-launched UTAP-22 is a ground-launched derivative of the BQM-167A aerial target drone that has demonstrated its ability to operate in swarms and as a loyal wingman. You can read more about both of these drones here and here.

Kratos also notably received permission to sell the UTAP-22 to foreign customers in Europe and Asia who otherwise meet the requirements of American export regulations, in March 2018. The company also said that it had at least four previously unannounced tactical drone projects in the works in a call with investors and media to discuss quarterly earnings in November 2018. One of these in-development designs is probably a derivative of the XQ-58 with a swarming, autonomous capability.

The American company would seem to be a leading contender for the U.K.’s new swarming drone tender, if it hasn’t already proposed its XQ-58 or a derivative thereof. Since 2017, the RAF’s own Rapid Capabilities Office has been exploring options for a lower-cost attritable UCAV as part of the Lightweight Affordable Novel Combat Aircraft (LANCA) program.

“The conversation is open,” RAF Air Vice-Marshal Simon ‘Rocky’ Rochelle, Chief of Staff, Capability and Force Development, told the Royal Aeronautical Society in 2018. “It’s for everybody to come and show us what can be delivered its effectiveness. We are truly looking for disruption in that area too.”

Work already underway as part LANCA may be part of Defense Secretary Williamson’s optimistic schedule for the new drone swarm squadron, as well. Any developments the RAF is pursuing under that project would almost at least help inform the service’s drone swarm requirements.

However, LANCA’s stated emphasis has been more focused on the development of a higher-end UCAV than the XQ-58 that would have greater capabilities overall and fighter jet-like performance. This unmanned aircraft would be able to work closely with future sixth generation manned fighters, such as the U.K.’s now-in-development Tempest.

Since 2005, U.K.-headquartered BAE Systems has been working on a proof-of-concept UCAV testbed called Taranis, which could serve as the basis for a design that is better suited to meeting this more robust requirement. It could also offer an upper-tier capability for any new drone-swarm unit.

It may turn out that the Ministry of Defense’s rush to establish a drone swarm squadron with a lower-end type of aircraft, such as the XQ-58, would serve as the stepping stone to establishing full UCAV squadrons, as well. In the past, BAE has stated that an operational UCAV based on Taranis would be operational “post 2030,” which is the same timeframe when the United Kingdom hopes to begin taking deliveries of the Tempest fighter jets.

Completing the tender for the initial drone squadron and the full development of the selected system within the next three years would give RAF personnel ample time to begin developing tactics, techniques, and procedures for employing full on UCAVs in the following decade. The need for an attritable system, which would be a lower-cost, high-volume fleet, would be somewhat less pressing after the acquisition of a costlier and lower-density high-end platform, but It is becoming ever more apparent that one really doesn’t fully displace the other capabilities wise.

Another possibility is that the U.K. Ministry of Defense has bought into an ongoing, but clandestine American unmanned combat air vehicle program. You can read all about how the U.S. proved the game-changing technology nearly two decades ago, before seemed to disappear entirely from view and from the USAF’s vernacular and vision of the future, in this past special feature of ours.

Fast forward to today and there are many indicators that this technology was dragged into the ‘black’ world of compartmentalized programs. If this was indeed the case, it is an unfortunate move for a number of reasons we discussed in our previously linked feature, but there are signs that this may be coming to an end. These include a big hiring push for an unnamed production program at Lockheed Martin’s Fort Worth facility and persistent silence from the U.S. Air Force’s leadership on the topic even as peer state competitors around the globe are now openly developing this capability themselves.

By joining forces on a UCAV initiative, the United States and the United Kingdom could pool their resources and achieve better economies of scale and deeper levels of interoperability. There is a long history of this between the two countries, but it’s becoming an increasingly common arrangement as of late. In recent years, the Royal Air Force has adopted the RC-135 Rivet Joint, P-8 Poseidon, and MQ-9 Reaper instead of developing indigenous solutions to satisfy those mission sets. The F-35B Joint Strike Fighter is another example of this.

The U.S. government offering its friend with a ‘special relationship’ access to one of its most secretive and cutting-edge combat aircraft programs that is in a pre-operational, but maturing state wouldn’t necessarily be unprecedented, either. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan personally invited Prime Minister Magret Thatcher into the F-117 stealth fighter program. You can read all about this historic and at the time very secret overture here.

When the offer was made, the F-117 program was growing and evolving into an operational capability under a veil of darkness at its desolate base in Tonopah, Nevada. This is the same place where a pocket force of semi-operational networked UCAVs would most likely live today and there continues to be evidence of just that being the case.

In order for shared UCAV program to grow into a scale that would be strategically impactful and would truly leverage its unique swarming concept, moving it from the shadows and into the light for full-rate production would be essential. Williamson’s comments could reflect this reality. Also, by taking part in an American UCAV program, the Royal Air Force would be far better prepared to introduce an indigenous one, potentially based around a Taranis successor, in the years to come.

Moving a greater share of the aerial combat burden from manned to unmanned aircraft is already attractive for many smaller countries due to the savings in pilot training and infrastructure on top of the lower cost of these platforms compared to manned aircraft, in general. As time goes on, UCAVs will only become more advanced and more autonomous, offering capabilities very close to manned fighter jets and other combat aircraft, all at a lower cost. Based on how they’re programmed, a UCAV swarm can also act far faster in a coordinated manner than a human-controlled team and better exploit its capabilities to their maximum potential at all times. The drones in the swarm also offer added range and lower observability that manned platforms can’t provide, as well.

It’s even less surprising that the United Kingdom is increasingly interested in pursuing this type of unmanned air combat capability in light of the economic uncertainty surrounding the country’s upcoming departure from the European Union. Existing budget austerity and defense cuts already call into question how realistic it is for the country to develop a new manned stealth fighter at all, even with possible

The swarming drone program will also help ensure that the United Kingdom can continue to compete in the air combat space with peer competitors in the future. This is especially true with regards to China, but also to a lesser extent Russia, as both of these countries continue to invest significant resources into UCAVs and swarm capabilities.

All told, the United Kingdom’s new drone swarm plans could be the beginning of a more significant transformation of the RAF with a greater emphasis on unmanned platforms going forward.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com