For decades, there have been reports, which we at The War Zone

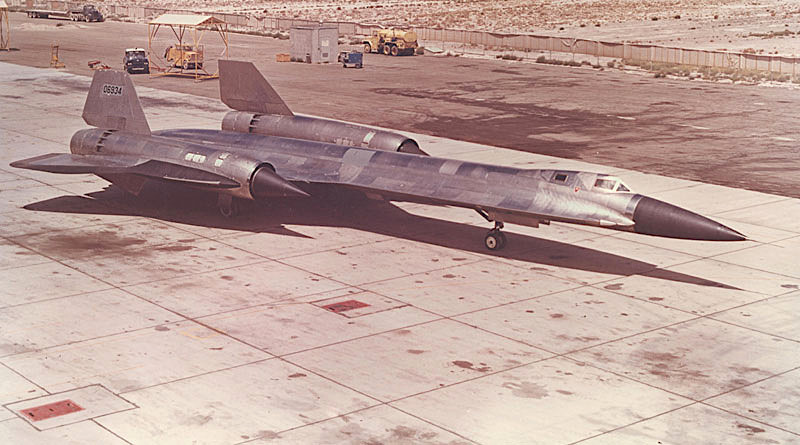

recently examined in depth, about the possible existence of a U.S. military space vehicle that would hitch a ride on a supersonic mothership aircraft into the upper atmosphere, after which it would blast itself into orbit. There remains only circumstantial evidence that any such combination of aircraft and space vehicle ever came to be, but declassified documents show that there was interest in using the Central Intelligence Agency’s high- and fast-flying A-12 Oxcart spy plane for a very similar satellite-launching role nearly 60 years ago.

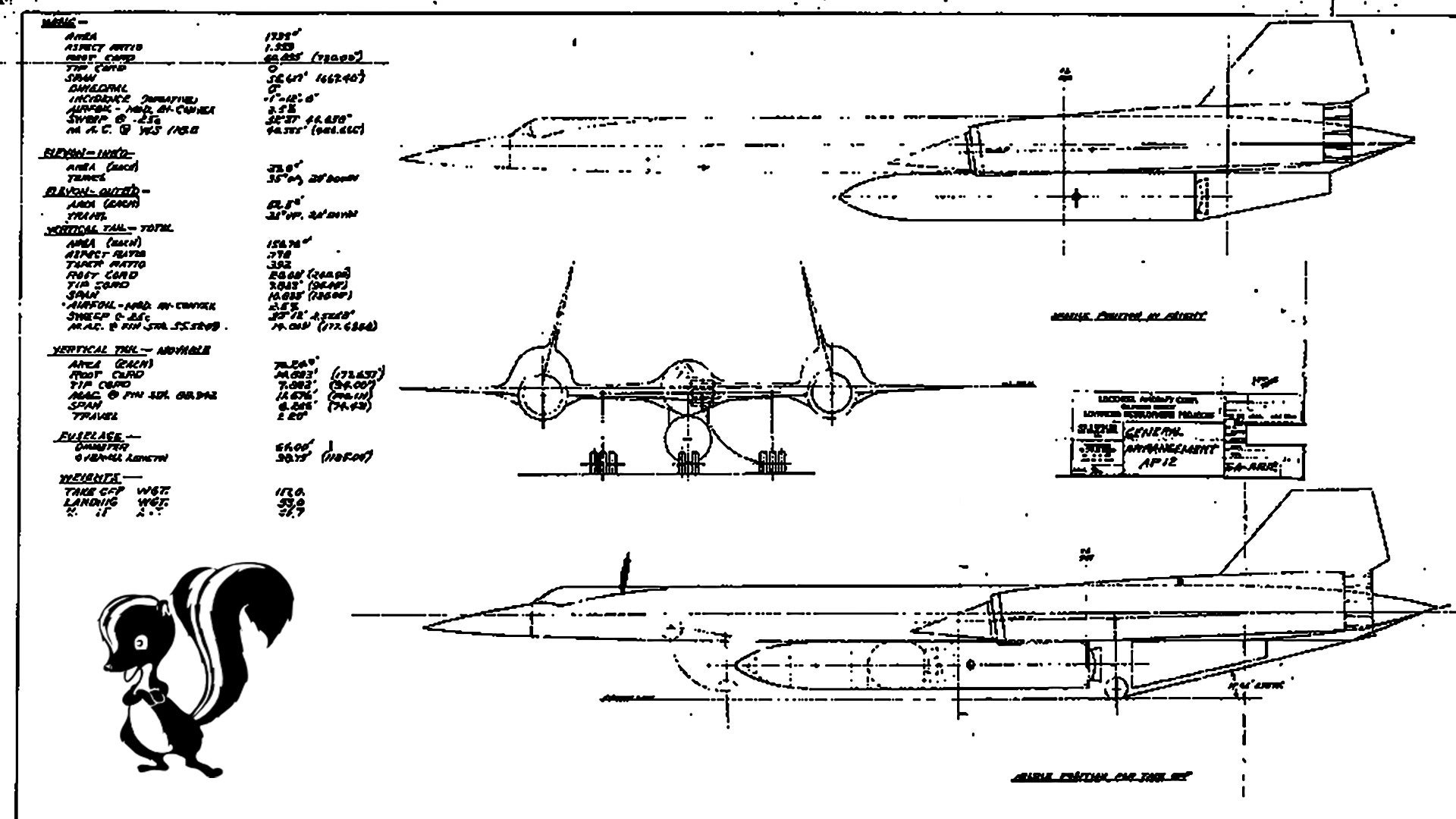

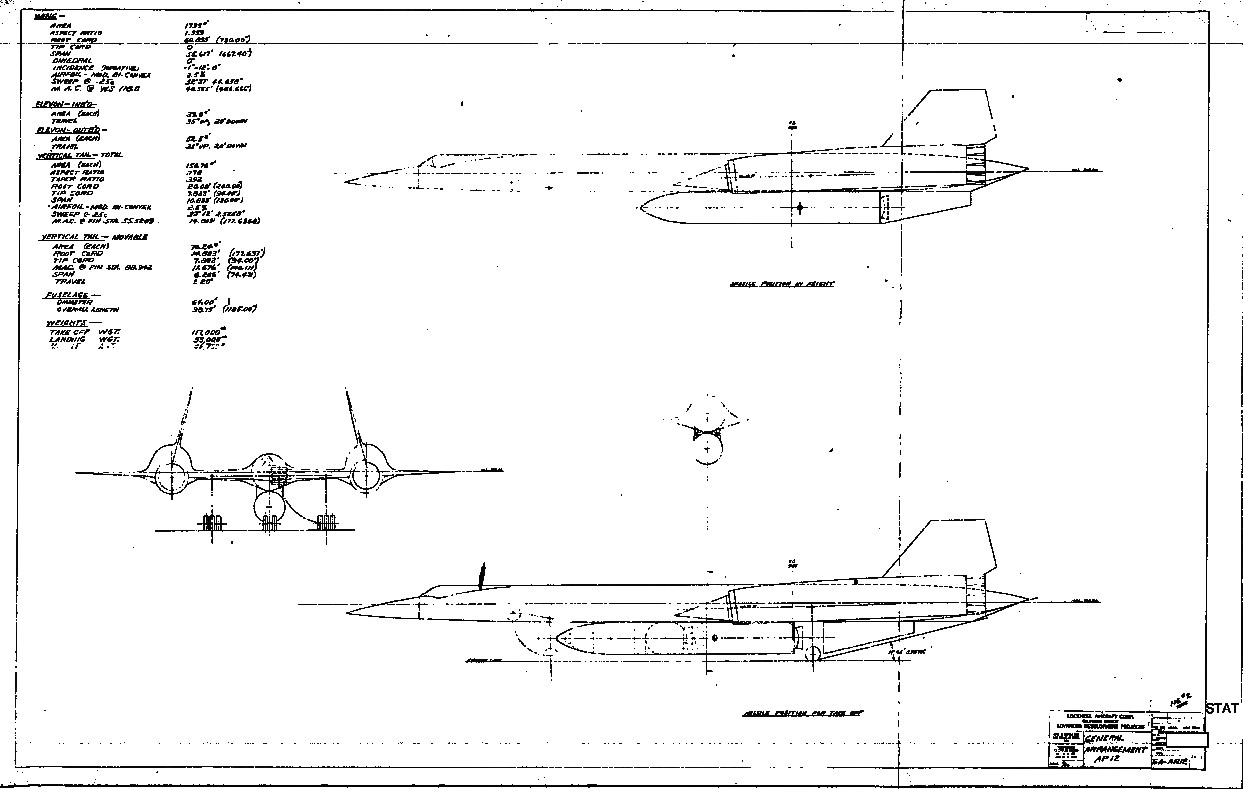

Lockheed’s Skunk Works, which had developed the A-12, the progenitor of the U.S. Air Force’s SR-71 Blackbird, produced the feasibility study on using the aircraft as a space launch platform in September 1962. It is unclear whether the CIA or the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the super-secret U.S. intelligence agency primarily responsible for satellite intelligence, requested the report initially, but the CIA paid for it. The very existence of the NRO remained officially classified until 1992.

CIA, with input from NRO, released the document in 2002 with some redactions, but placed it in its CIA Records Search Tool (CREST) electronic database, which was only accessible via computer terminals at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland at the time. After fighting to maintain this obtuse arrangement for years, a three-year lawsuit finally pushed the Agency to put the documents online in January 2017.

“The purpose of this report is to review the technical evaluation concerning the feasibility for utilization of an A-12 vehicle to launch an orbital reconnaissance vehicle over the Soviet land area,” the study’s introduction explains. “As a result of the preliminary evaluation, a configuration is recommended.”

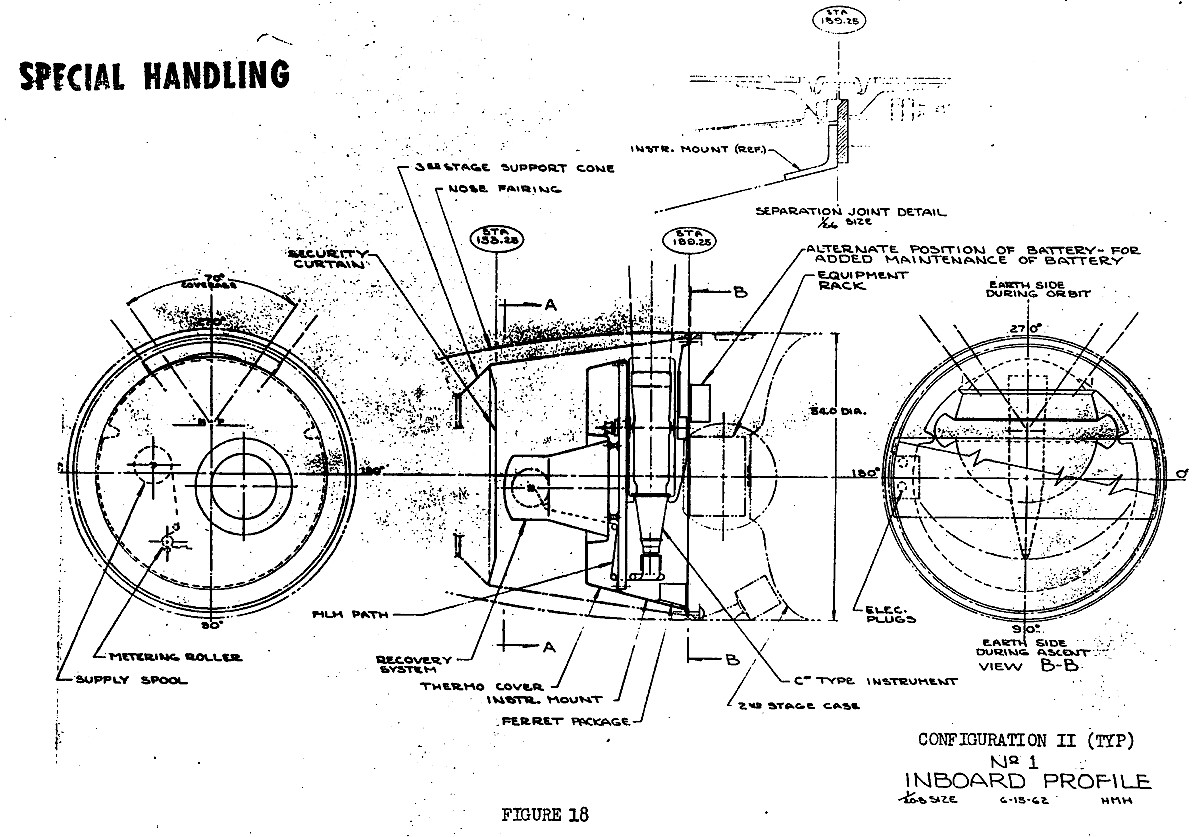

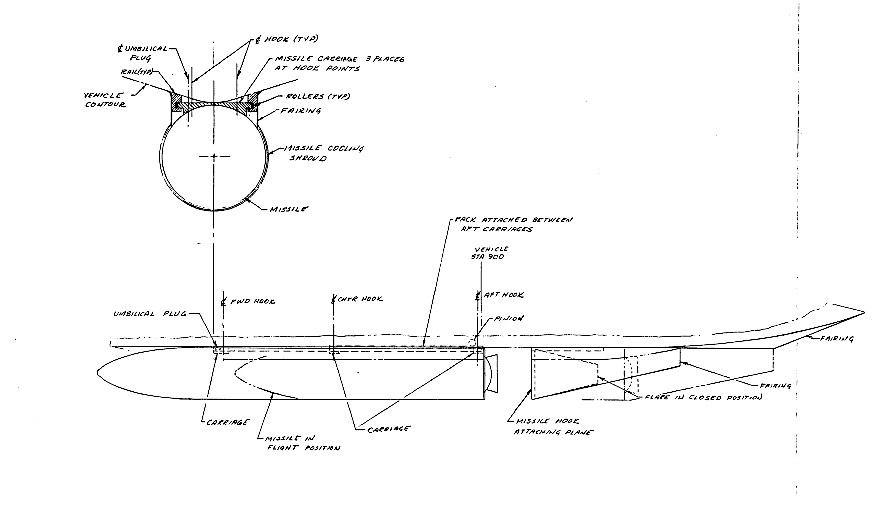

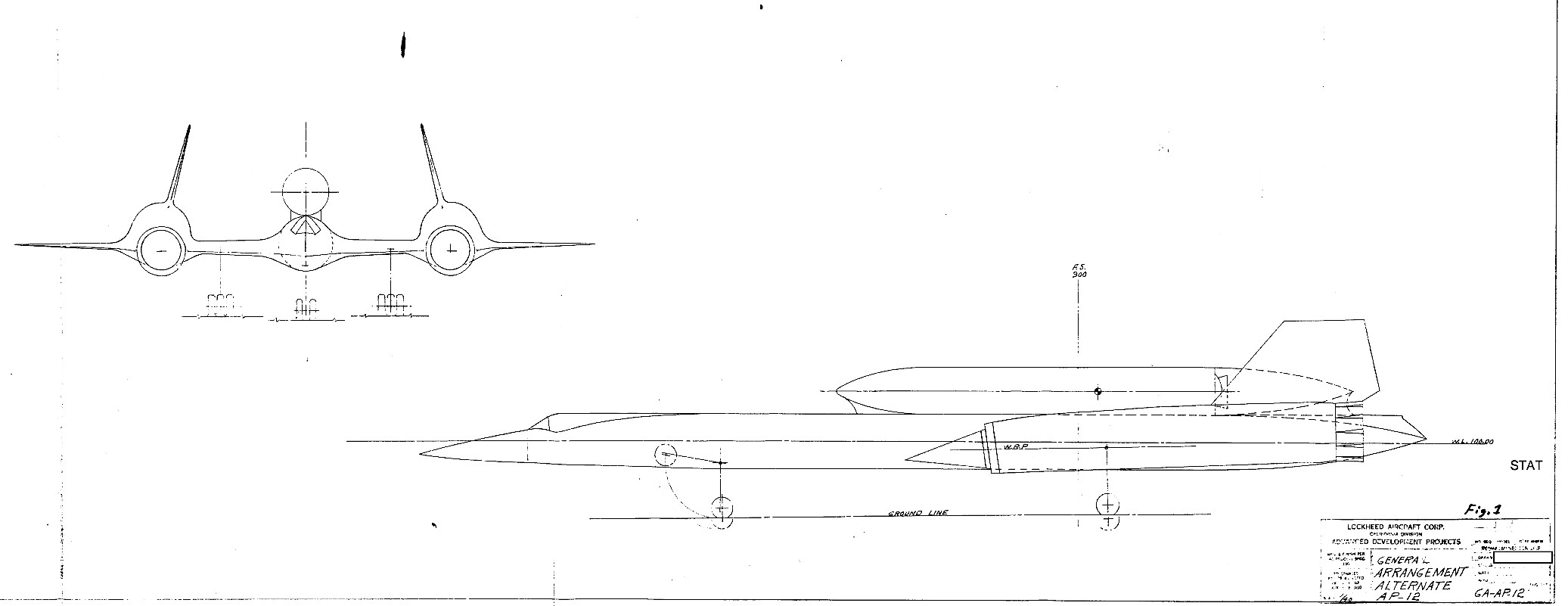

The proposed modified A-12 aircraft would carry a satellite and its booster rocket on a set of rails forming a track along the bottom of the aircraft’s fuselage. The single-seat spy plane would also need an additional crew member to help with “navigation, approach [to the launch point], and separation maneuvers.”

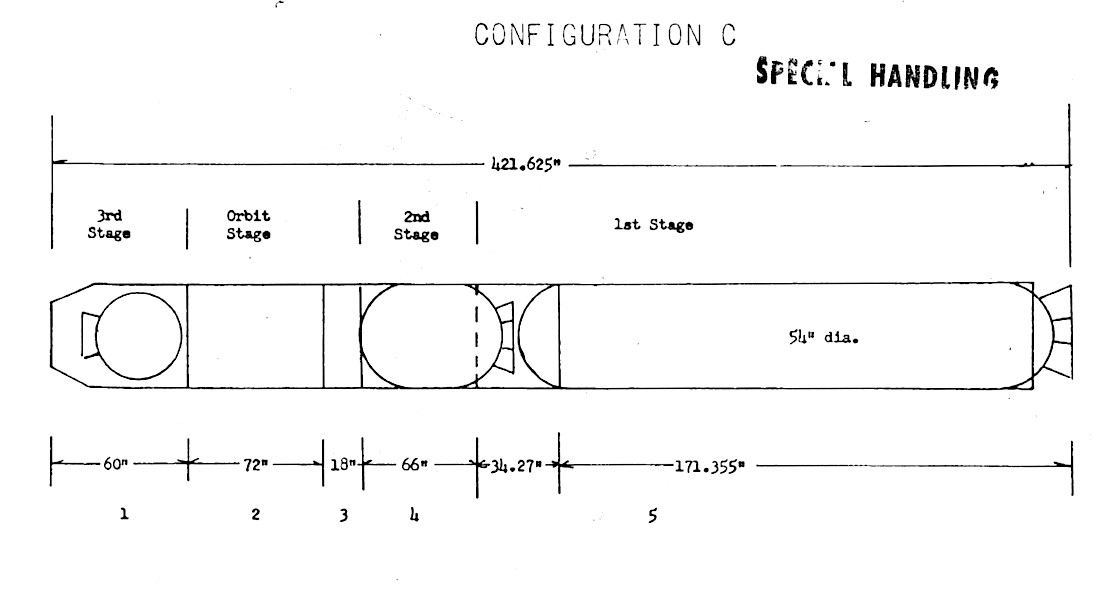

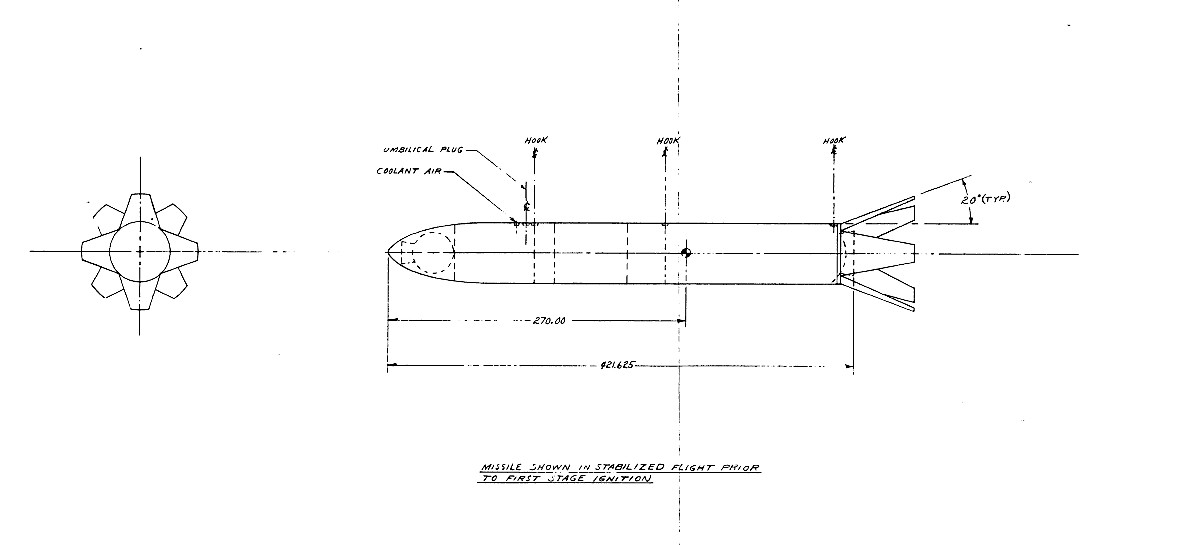

The complete payload, a modified Polaris A3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), another Lockheed product, would be more than 420 inches long and more than 54 inches in diameter. The new mothership would be designated the AP-12, with the “P” likely standing for Polaris.

Lockheed’s study focuses almost exclusively on the AP-12 aircraft. A companion report from Lockheed on the air-launched satellite and its booster do not appear to be available through CREST.

A separate study on an “air-launched, single-pass, low-orbit reconnaissance system,” which predates the AP-12 report, is available and does provide more detail on three possible payload configurations. CIA also released this document after NRO reviewed its contents.

This second document explained that the original requirements for this aerial space launch concept called for a satellite and booster that would be smaller than Polaris. As such, the first configuration was less than 360 inches long and only 40 inches wide. These dimensional stipulations subsequently got relaxed for unspecified reasons to allow the use of a modified version of the SLBM, according to the report.

The second configuration was essentially a standard Polaris A3 with a satellite in place of the nuclear warhead. The third and final configuration, which matches the dimensions in the Lockheed AP-12 report, featured an additional third stage to improve performance. Additional proposals from Lockheed included adding tail fins to the end of the booster for added stabilization after release from the mothership, but before the rocket motor actually ignited.

The “low-orbit reconnaissance system” was a small spy satellite that could carry one of three different cameras. Two of these were already in service at the time on the Corona spy satellites. A third stereoscopic panoramic camera design was under development in 1962 when the CIA and NRO were investigating this air-launched concept.

Lockheed’s design study says that the complete payload design was long enough to extend rearward beyond the main landing gear when loaded onto the AP-12. However, the report adds that ground clearance would not be any more of an issue during takeoff than with a standard A-12. The plane’s landing gear itself would need modifications to accommodate the changes in weight and overall aircraft handing during both takeoff and taxing, though.

To further help keep the aircraft stable on the ground and in flight, the AP-12 would only carry half the fuel load of a standard A-12 and the payload would shift rearward along the rails after takeoff to assume an “optimum cruise” position. If a fault were to occur before launch, the crew could still land the plane with the payload locked to the rear.

Lockheed said that it had otherwise determined that the basic A-12 had sufficient power, cooling, and other supporting functions to carry the satellite-tipped Polaris missile. It does say that the mothership aircraft could still require some modifications to the air cycle system the Oxcart used to cool its systems.

A backup plan was to use the liquid cooling system Lockheed had developed for the U.S. Air Force’s AF-12 Kedlock high-altitude, high-speed interceptor aircraft, which was derived from the A-12. This aircraft eventually became known as the YF-12A and would have carried a payload of AIM-47 Falcon long-range air-to-air missiles, which could be equipped with nuclear warheads.

President Lyndon Johnson declassified the existence of YF-12A in 1964, in part to conceal the still-secret A-12. With the Kedlocks flying publicly from Edwards Air Force Base in California, the U.S. government could dismiss any sightings of Oxcarts operating from Groom Lake in neighboring Nevada, better known as Area 51, as people simply seeing the interceptors. The Pentagon finally canceled the Kedlock program entirely in 1968.

With regards to the AP-12 mothership, the AF-12/YF-12A would no doubt have otherwise served as a basis for that aircraft, at least in part, given that it was also a two-seat design. As noted earlier, the A-12 and AF-12/YF-12A both led to the development of the Air Force’s two-place SR-71 Blackbird spy plane.

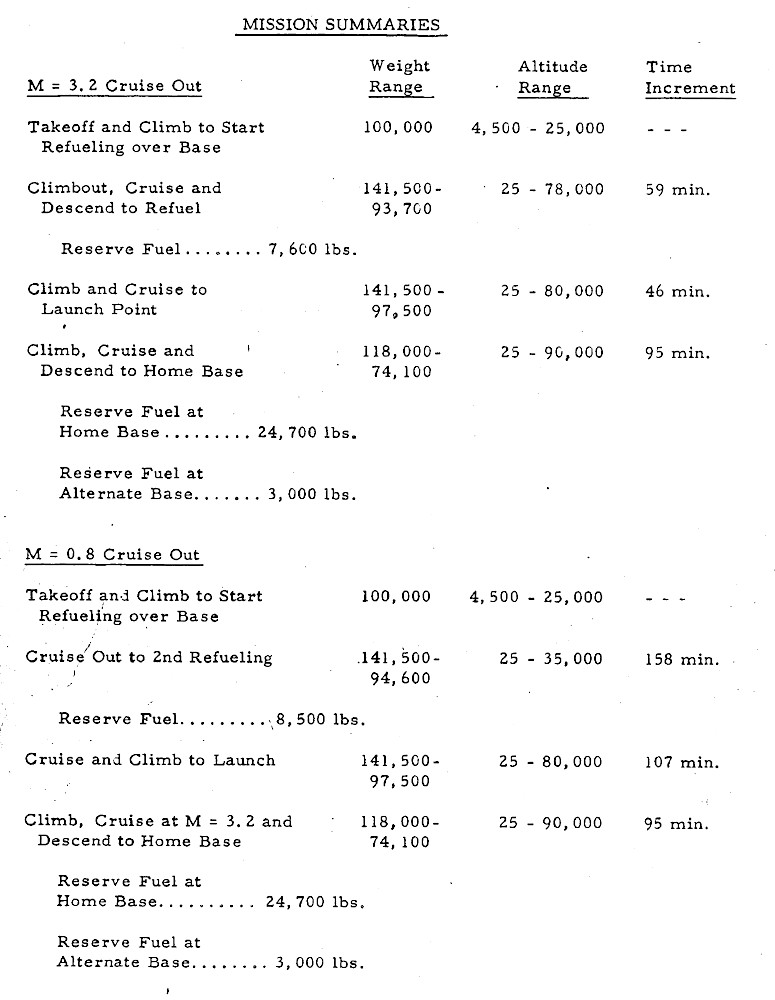

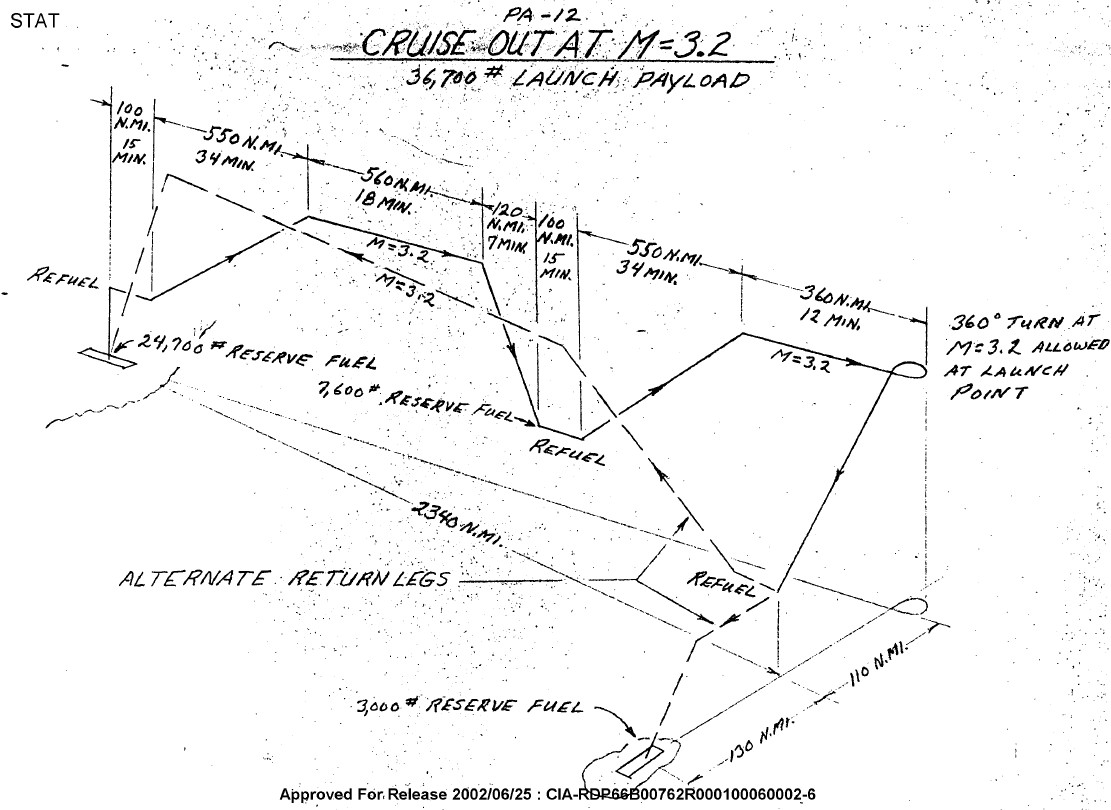

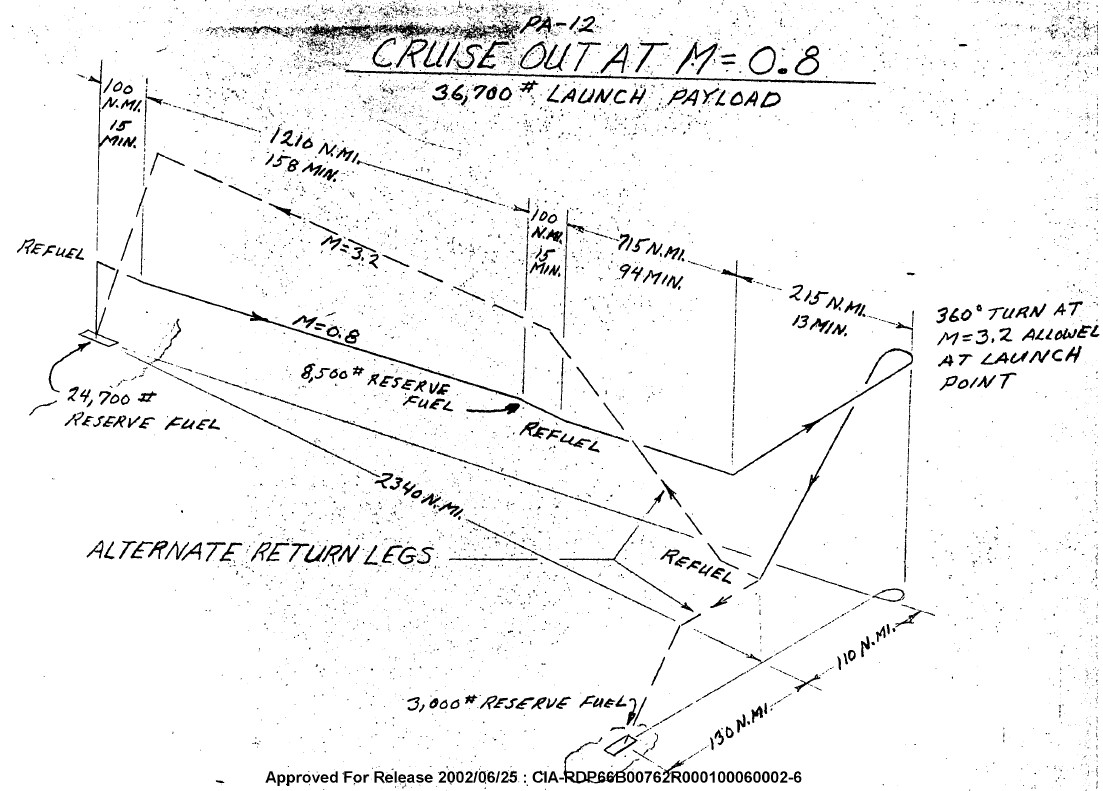

Lockheed’s study provides two notional mission profiles, one involving the aircraft cruising back to base at supersonic speeds after launching the satellite and another with the aircraft making the return trip at subsonic speeds.

In both cases, the assumption is that the plane would fly from a base inland in the Contiguous United States more than 2,340 miles to a position east of Hawaii. The two mission profiles also required the mothership to refuel in flight near the base after takeoff to fill its tanks to close to 100 percent capacity, before setting out into the Pacific, where it would refuel again.

Once there, the aircraft would conduct a pull-up maneuver while flying at Mach 3.1 at 80,000 feet and release the payload. Five seconds later, the booster rocket would ignite, blasting the satellite into orbit. Afterward, the AP-12 would return to base.

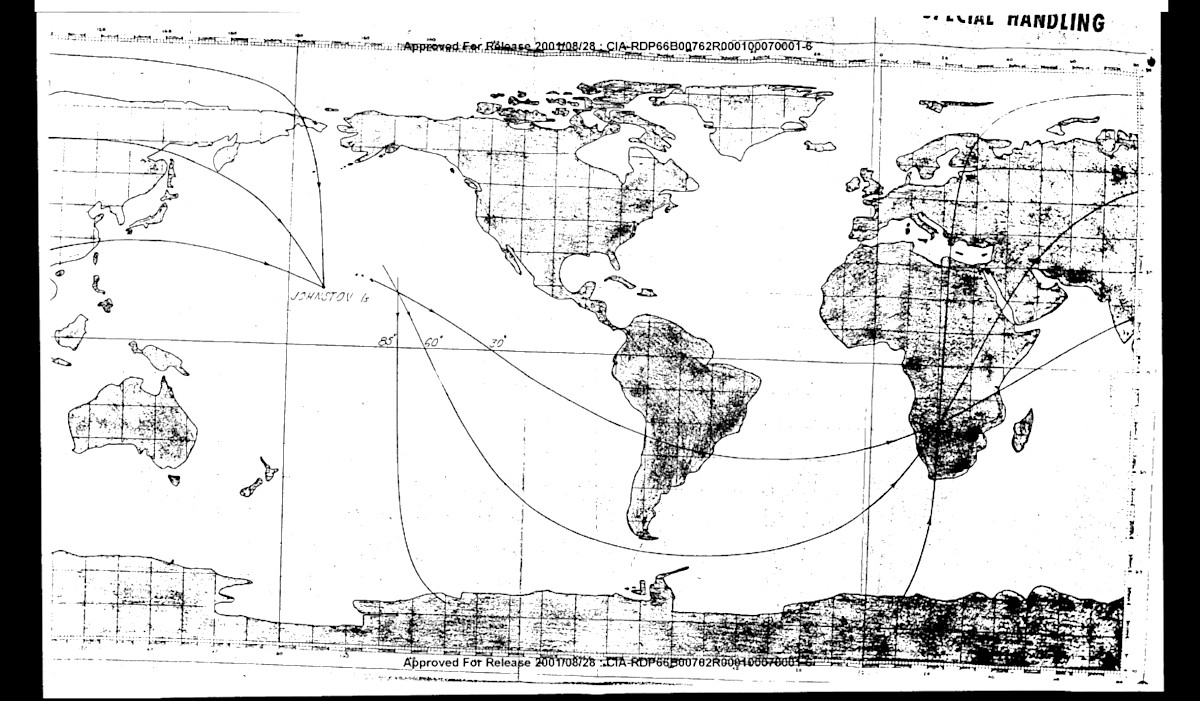

From the launch site, the satellite would enter a shallow orbit, passing over South America, the South Atlantic, or Antarctica, before heading up over Africa and the Middle East toward the Soviet Union, according to the separate report on the “low-orbit reconnaissance system.” Depending on the exact mission profile, it might pass over India and the People’s Republic of China, which were also major areas of interest for the United States in the 1960s.

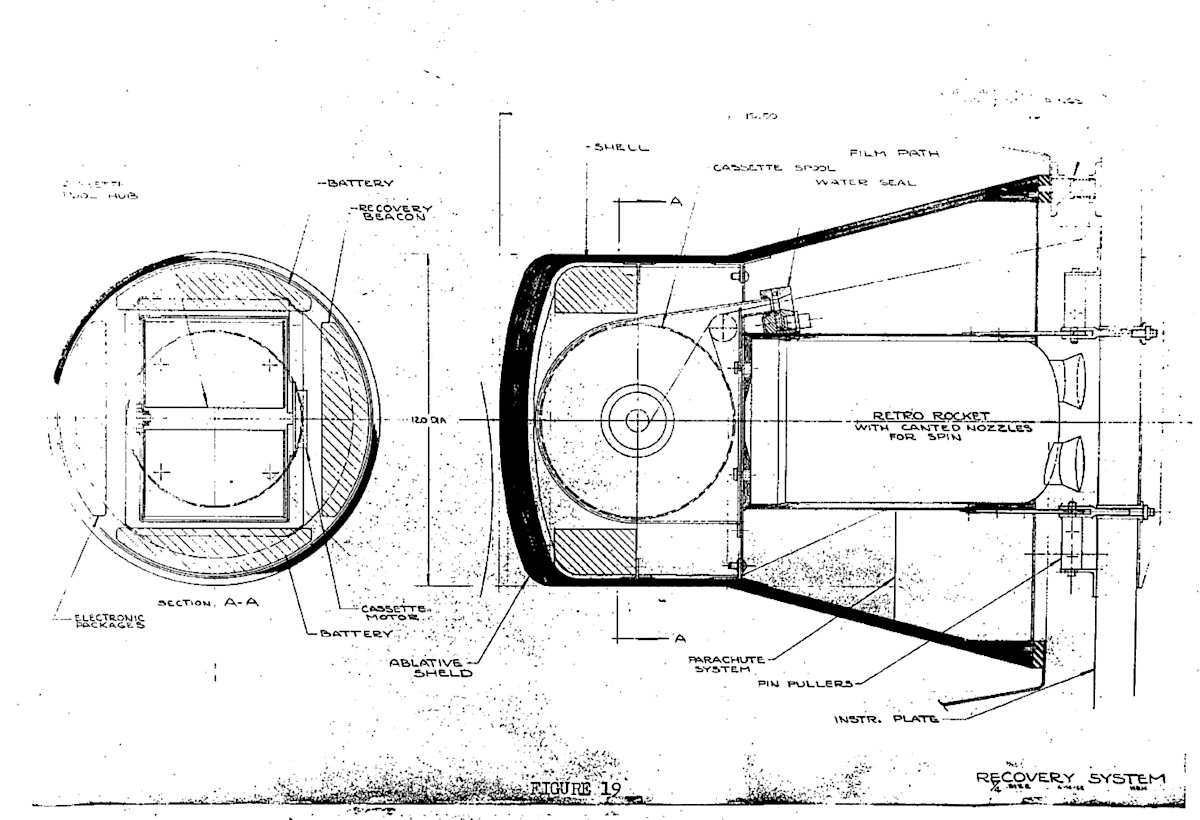

If all went according to plan, a recovery capsule containing the film canister would detach from the rest of the satellite and re-enter the atmosphere over the Pacific to the West of Hawaii. It would automatically deploy parachutes for a safe recovery in mid-air using specialized C-119 Flying Boxcar and C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft, and later or helicopters.

The Air Force, together with the CIA and NRO, developed these aircraft and the associated operating concept in the 1950s to grab descending film canisters from more persistent spy satellites. This remained a key method of retrieving imagery and other data from satellites, but became increasingly obsolete as it became more practical for space-based systems to send imagery and other data wirelessly down to ground stations.

The documents available in CREST do not offer any clear indication of how far the CIA and NRO moved ahead with the AP-12 concept or whether Lockheed actually converted any aircraft. The CIA’s public website on the Oxcart “family” does not mention the AP-12 at all.

The potential benefits of an air-launched space-based intelligence gathering system, especially at the time, are obvious. In 1960, the Soviet Union shot down Gary Powers as he flew his U-2 spy plane over their country, sparking an international incident.

Afterward, the U.S. government moved almost exclusively to spy satellites to collect imagery and other data about sensitive activities deep within the Soviet Union. However, satellites are relatively rigid tools that are difficult, if not impossible to rapidly reposition on short notice.

An air-launched satellite, or reusable space vehicle, offers added flexibility in orbits and can be more readily deployed to respond to new information. It also provides a system that is far less predictable than a satellite moving in a regular orbit, which makes it harder for an opponent to conceal their activities.

The AP-12 concept, and those that followed, also require less infrastructure than traditional space launches, have a faster turnaround time for follow-on missions, and cost less. At the time, it could also have preserved A-12’s role in conducting intelligence operations over the Soviet Union without having to put the aircraft themselves at risk.

With all this in mind, it is interesting to note that Lockheed’s 1962 design study had also investigated an A-12 configuration with the payload mounted on top of the aircraft. The report describes this arrangement as not only sub-optimal, but also potentially dangerous.

“Asymmetric fuselage loads require a severe structural beefup to support this concept,” the design study explained. “Separation safety is considered much more critical, and additional separation pre-ignition timing degrades performance, compared to the belly launch. The [space launch] vehicle affects upper surface flow and reduces the predictability of the directional stability compared to the underside installation.”

This is significant because around the same time Lockheed was working on the AP-12, it was also beginning work on what would become the supersonic D-21 drone, also known by its codename Tagboard. The original plan was for a modified A-12, known as the M-21, to carry the unmanned aircraft on top and carry it to a designated launch point.

This combination was never deployed operationally, though. Test launches in 1966 confirmed the concerns that Lockheed had with the top-mounted AP-12 configuration in spectacular and ultimately deadly ways.

During the very first test launch, the D-21 separated from the M-21, but remained dangerously close to the aircraft before speeding off on its way. In the fourth test flight, the mothership’s crew attempted to launch the drone from a straight and level flight profile with catastrophic results. The unmanned aircraft’s engine suffered a fault and it crashed back into the carrier aircraft, destroying them both.

The two pilots ejected, but only the pilot, Bill Park, survived. The Launch Control Officer, Ray Torrick, drowned. In the end, the only operational Tagboard launches occurred using a specially configured B-52 bomber. None of the four missions, all of which occurred over China, were successful and the entire program came to an end in 1971.

But, as with the air-launched satellite concept, Tagboard was a product of the post-Gary Powers desire for a more rapidly employable, penetrating long-range intelligence gathering platform that could reach deep into the Soviet Union and Communist China. The drone offered the potential of a lower-risk alternative to direct manned overfights at the time.

Other documents that the CIA and NRO have released regarding the status of both spy plane and satellite programs from the same time frame point to still-classified developments that could include an air-launched satellite system. One NRO report from 1963 mentions Oxcart and Tagboard, along with Idealist, the codename for the U-2. It also includes the codenames Corona, Laynard, and Gambit, which refer to various spy satellites.

But a seventh codename remains redacted. The existence of the codenames Isinglass and Rheinberry, which refer to potential A-12 or SR-71 replacements, has long been declassified now, even if many details of those programs remains hidden away. This makes it unlikely that this redacted entry refers to either of those programs.

We know that Lockheed continued developing top-mounted launch options for the A-12 family for years after deriding the general idea internally. It is possible that this concept proved to be just as complicated, costly, and disappointing as Tagboard, at least at the time, and the CIA, NRO, and Air Force shifted their attention and resources elsewhere. On the other hand, they could have continued to work on a mothership/space vehicle combination in their preferred configuration.

In the end, we don’t have any clear evidence that Lockheed’s concept progressed beyond the drawing board, but there is also much that remains classified about the A-12 and SR-71 programs.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com