The U.S. Air Force has accepted the first Boeing KC-46A Pegasus tanker, an important milestone for the troubled program. However, the initial batch of aircraft will still have serious problems with their remote vision and refueling boom systems, meaning that the planes remain years away from reaching their full operational potential.

Foreign Policy was the first to report on the agreement between the Air Force and Boeing to proceed with the deliveries of the aircraft, citing anonymous sources, on Jan. 10, 2019. Defense News then reported that the Chicago-headquartered planemaker had agreed to fix the remaining deficiencies and that the Air Force’s top leadership reserved the right to withhold full payment for the planes – up to $1.5 billion in total if the service docks the company for each of the 52 aircraft in the first batch of planes – until it sees real progress.

“The KC-46A is a proven, safe, multi-mission aircraft that will transform aerial refueling and mobility operations for decades to come,” Leanne Caret, President and CEO of Boeing Defense, Space and Security, said in a subsequent press release. “We look forward to working with the Air Force, and the Navy, during their initial operational test and evaluation of the KC-46, as we further demonstrate the operational capabilities of this next-generation aircraft across refueling, mobility and combat weapons systems missions.”

Boeing says that now that the Air Force has accepted the KC-46A in its present state, the company will begin delivery of four of the tankers to the premier 22nd Air Refueling Wing at McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas as early as February 2019. After those planes arrive, another four will go to the 97th Air Mobility Wing at Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma.

The acceptance and up-coming deliveries are a big deal for the KC-46A program, which has been mired in delays and controversy since Boeing won the Air Force’s KC-X competition in 2011. That decision itself followed nearly a decade of earlier, scandal-ridden Air Force attempts to procure a new tanker aircraft. Notably, in 2004, Darleen Druyun, a Boeing executive who had previously been the Air Force’s top procurement official, went to federal prison after receiving a conviction on corruption charges relating to an earlier tanker program.

The Air Force was supposed to have received a fleet of 18 KC-46As, the first tranche in the total initial buy of 52 aircraft, by the end of 2017 and reach an initial operational capability with the type shortly thereafter. Between 2011 and 2017, continuing technical difficulties, which you can read about in more detail here, repeatedly pushed this schedule back. This continued into 2018, leading to an unusually public spat between the two parties over the program’s progress. Boeing’s contract is firm, fixed-price, and that company has already had to pay more than $3 billion of its own money to cover cost overruns.

Boeing had expected the Air Force to finally accept the first KC-46 in December 2018, but this was reportedly delayed by former Secretary of Defense James Mattis’ resignation. Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan is a former Boeing executive and has had to recuse himself any dealings related to the company, further lengthening the process for the Pentagon to formally approve the Air Force’s plans.

But Boeing and the KC-46A are hardly out of the woods. As noted, the company was supposed to have delivered 18 aircraft in total back in 2017 and it is unclear whether it will completely fulfill that part of its contract by the end of this year.

Beyond that, the aircraft the Air Force is getting now still have serious problems that neither the service nor Boeing expects to be completely resolved for at least another three to four years. The first of these is related to the refueling boom at the rear of the aircraft.

Aircraft that use this aerial refueling method must work with the tanker to force the probe at the end of the boom into a receptacle on their own plane. If the receiving aircraft can’t generate enough thrust, it might not be able to successfully establish the link and there is a risk that the connection might fail inadvertently in the middle of refueling.

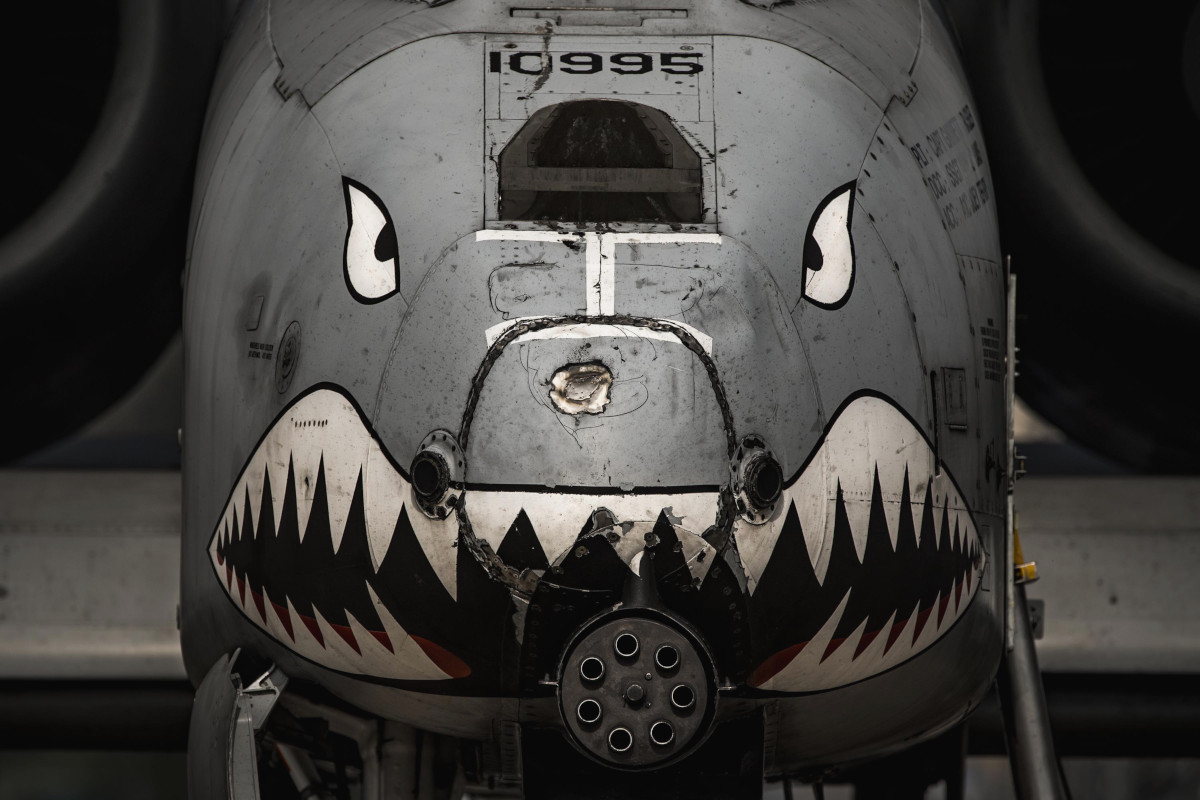

The KC-46A’s boom has a so-called “thrust resistance” of 1,400 pounds, according to Defense News. This is higher than the maximum threshold of certain U.S. military aircraft, including the A-10 Warthog ground attack aircraft.

Apparently, the Air Force did not specify the lower thrust resistance in the original contract and has now asked Boeing for a design change to meet this requirement. As such, since this is officially a new stipulation, the service has agreed to give the planemaker additional funds on top of the fixed deal to pay for the work.

This is an important concession on the part of the Air Force, which required Boeing to pay out of pocket for a separate boom-related software fix to prevent the probe from damaging the receiving aircraft. The two parties are still negotiating the exact cost for the revised boom design, but they expect the work to take around two years to complete.

A bigger issue remains with the Pegasus’ long-problematic Remote Vision System, or RVS. In the Air Force’s existing KC-135 and KC-10 tankers, an operator at the rear of the aircraft helps guide the boom into the receiving aircraft. On the KC-46A, this individual performs their task remotely from the main cabin via an advanced stereoscopic video feed that presents a blend of two-dimensional and three-dimensional imagery from an array of electro-optical and thermal cameras at the back of the plane.

“There is a slight difference between the motion viewed in the RVS versus what is actually occurring in the physical world,” an Air Force official explained to Defense News. All of those things can create a depth compression and curvature effect.”

What this means is, depending on shadows, glare, and other factors, the boom operator might not have an accurate understanding of what’s going on behind the tanker, leading them to over-compensate and move the boom erratically, putting potentially dangerous strain on the boom itself and risking hitting and damaging the receiving aircraft. Additional studies have warned that certain individuals may simply be predisposed to eye strain, headaches, vertigo, and other vision issues when using the system for a protracted period of time, limiting the pool of people who could take on the boom operator job on KC-46s at all in the future.

As part of the acceptance plan, Boeing has agreed to completely overhaul the RVS, which could entail both hardware and software changes to the aircraft, and do so at its own cost. The Air Force expects it to take between three and fours years to simply to develop the replacement system. There is no timeline for how long it might then take to modify any aircraft the service has taken delivery of up to that point.

There have been other deficiencies that Boeing has been working to resolve, as well, and it is unclear how close these are to getting fixed. This includes the boom striking the receiving aircraft, which is especially problematic for stealth aircraft, such as the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Damaging the special radar absorbent skin on these aircraft could have a direct impact on their ability to hide from hostile radars. There is a growing, separate discussion about how well a non-stealthy tanker such as the KC-46 will be able to support stealthy manned and unmanned aircraft during any future high-end conflict, in general.

With these major issues remaining, it’s unclear how useful the aircraft will be to the Air Force in their present state. They will definitely serve a purpose in priming the training pipeline for Pegasus crews and getting personnel accustomed to the new tanker. How valuable this training can be, especially for boom operators, if there are major changes still to come, is certainly debatable, though.

The Pegasus is supposed to undergo initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E) this year, leading to the Air Force declaring an initial operational capability with the type sometime afterward. It’s not clear how well it will be able to meet the ITO&E criteria if the thrust resistance and RVS issues remain unresolved. This could limit the KC-46’s operational utility, regardless of whether the Air Force decides to declare it has reached an initial operational capability in the next few years until these problems are conclusively fixed.

On top of the issues with the Pegasus itself, there is the matter of second-order impacts on the Air Force’s plans to retire older tankers, which could lead to additional, parallel spending on upgrading existing aircraft or contract aerial refueling services. The service still hopes to eventually have a fleet of nearly 180 KC-46s, as part of a broader push to expand its total combat force structure.

All told, the acceptance of the first KC-46 is a significant step forward for the program, but it is clear that the Air Force and Boeing still have a long way to go before the new tankers are truly ready for action.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com