In the aftermath of the abortive attempt to rescue American hostages in Iran in April 1980, the U.S. military dramatically overhauled and expand its special operations forces and their capabilities. Among other things, it touched off nearly 40 years of programs and initiatives seeking to develop a stealthy transport aircraft that could pierce through dense enemy air defenses and then be able to land and take off inside extremely confined spaces.

The world changed yet again with the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, D.C. on Sept. 11, 2001. The Global War On Terror that followed required a monumental shift in Pentagon planning. Bolstered by large budget increases, the U.S. military’s new focus would be on rapidly confronting asymmetric actors and rogue states. Money poured into the special operations community to take on this new brace of threats, which included an intensified requirement to clandestinely gain access to the airspace of friendly and unfriendly countries alike.

This was best exemplified by the rise of a penetrating and persisting stealth reconnaissance drone, the RQ-170 Sentinel, a craft with capabilities that had been sought after for decades and that would have been designed in part to work directly with any sort of stealthy special operations transport, feeding it surveillance in advance along the aircraft’s planned route and landing zone. There is abundant proof that the search for a stealthy special operations transport only intensified during this tumultuous decade, turbocharged by the new geopolitical realities around the globe and the tactical problems that the Pentagon was facing.

In this the second installment of our two-part investigation into the shadowy world of stealthy special operations transport, the first part of which you can find here, we pick up where we left off, and explore how the requirements for such an aircraft continued to evolve through the 1990s, into the first decade of the new millennium, and all the way to the present. We also offer an in-depth analysis of whether these aircraft actually exist, perhaps operationally in small numbers, or even still in a largely experimental form.

MC-X/Commando Spirit and M-X

After spending more than two decades advancing the idea of a stealthy special operations transport aircraft largely in secret, in the late 1990s, the Air Force did initiate a number of more public projects regarding such a plane. In addition, the service began pursuing a number of advanced general-purpose designs, with more limited low-observable (stealth) features, as well as improved short and vertical takeoff and landing abilities.

Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), which had only become a major command in 1990, started a project that it referred to variously as Commando Spirit and MC-X. This project’s goal was to develop a smaller aircraft to replace its MC-130 types specifically in the special operations forces insertion and extraction roles. The existing C-130s would continue to perform complimentary special operations cargo-carrying missions in lower risk environments and fulfill air-to-air refueling requirements for special operations helicopters.

The requirements the service laid out for Commando Spirit/MC-X described a smaller, stealthy aircraft and were virtually identical to those for the Special Operations Forces Transport Aircraft (SOFTA) – a payload capacity of around 4,000 pounds and a combat radius of more than 1,000 miles – an earlier program we at The War Zone discussed at length in part one of this investigation. But despite the clear relationship between the two efforts, McDonnell Douglas was in charge of the design study under the new program and completed its work, at least publically, in 1997.

There were also discussions about whether the same general aircraft design might be able to accommodate some form of onboard weaponry, akin to an AC-130 gunship, or extensive electronic warfare capabilities, which could have enabled it to take on additional missions. The proposed armed version was reportedly referred to variously as Commando Dagger or MA-X.

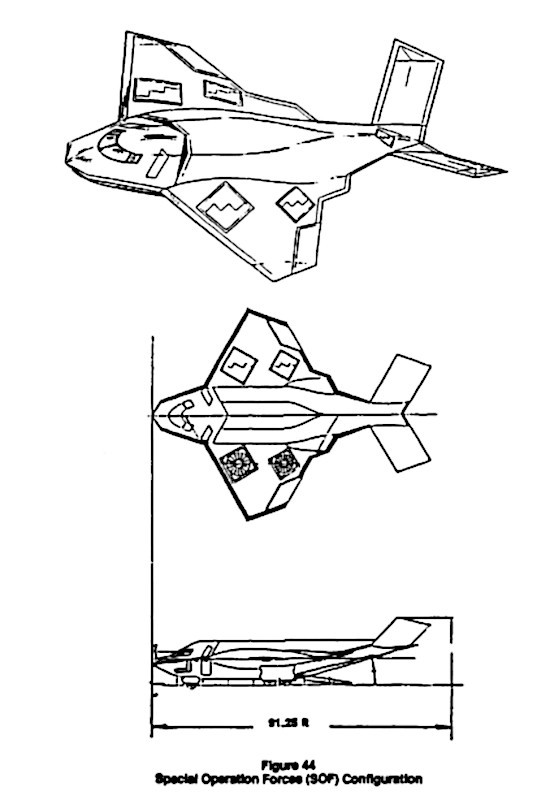

By 2003, with U.S. forces find themselves increasingly engaged in both Afghanistan and Iraq, Commando Spirit/MC-X had gotten renamed again, this time as the Advanced Special Operations Forces (SOF) Air Mobility Platform, or simply M-X. The parameters for a stealthy, short or vertical takeoff and landing capable aircraft smaller than a C-130 remained in place.

The consultancy Jacobs Sverdrup Technology Inc. received a contract of unknown value to conduct the analysis of alternatives on M-X designs, completing that work in 2004. AFSOC formally approved the requirement in 2005, setting out a prospective initial operational capability date of 2018 for whatever final design the service settled on. The final study contained cost analyses for purchases of between 10 and 100 aircraft, with a projected service life of 20 years.

It remains unclear whether or not Air Force Special Operations Command ever acted on this requirement directly via any of these programs.

AMC-X, Joint Heavy Lift, and ATT

By 2007, the Air Force and the U.S. Army were looking at a mix of at least two new vertical- and short-takeoff and landing capable aircraft programs, known as the Advanced Mobility Concept (AMC-X) and Joint Heavy Lift (JHL) respectively.

The latter of these efforts was primarily an Army initiative that eventually helped inform the Joint Multi-Role (JMR) and Future Vertical Lift (FVL) programs. The focus of JHL, and subsequently JMR and FVL, was on replacement rotorcraft for existing helicopters and, potentially, the V-22.

AMC-X, on the other hand, ostensibly looked to pick up where the 1970s Advanced Medium Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) Transport program, or AMST, had left off. AMST had led to the Boeing YC-14 and McDonnell Douglas YC-15, before the final product had morphed into the much larger Boeing C-17A Globemaster III many years later. The C-17 offered a blend of strategic and tactical airlift capabilities for more mainstream transport applications.

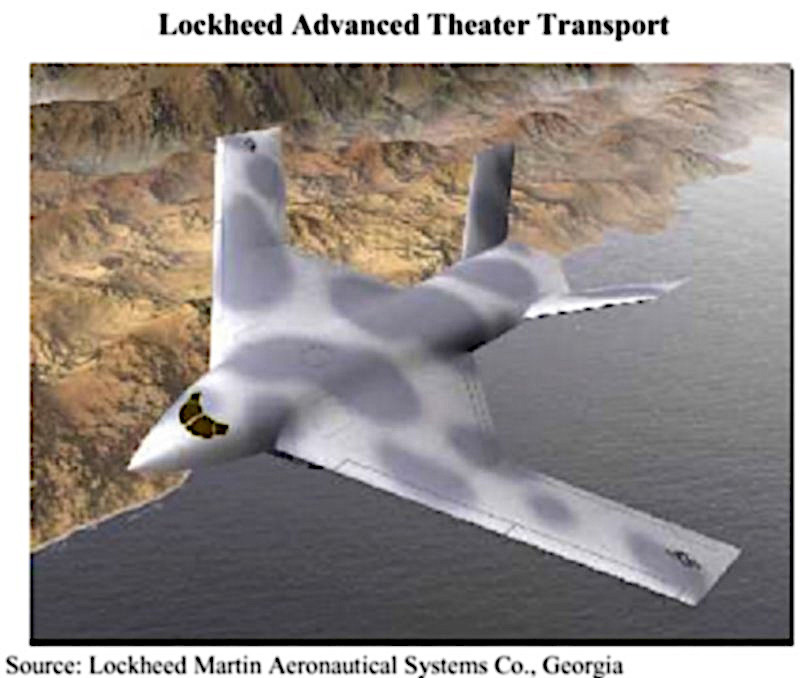

The new AMC-X was also supposed to act as a more direct follow-on for a separate 1990s program called the Advanced Theater Transport (ATT). This latter project had sought to create a C-130-sized airlifter with extreme short-takeoff and landing capabilities.

As with SOFTA and MC-X, the Air Force wanted the ATT to have a combat radius of more than 1,000 miles and expected the plane to fly a high-low-low-high flight profile to its destination and back. The proposed aircraft would have an exponentially greater load capacity than the notional planes in the earlier programs, though, at between 30 to 40 tons. With a 30 ton payload, the aircraft would have to be able to take off and land within a distance of just 750 feet.

Boeing and Lockheed Martin developed concepts for the ATT. Boeing, having acquired McDonnell Douglas in 1997, proposed a tailless, tilting-wing derivative of the C-17 with four turboprop engines, nicknamed the Super Frog.

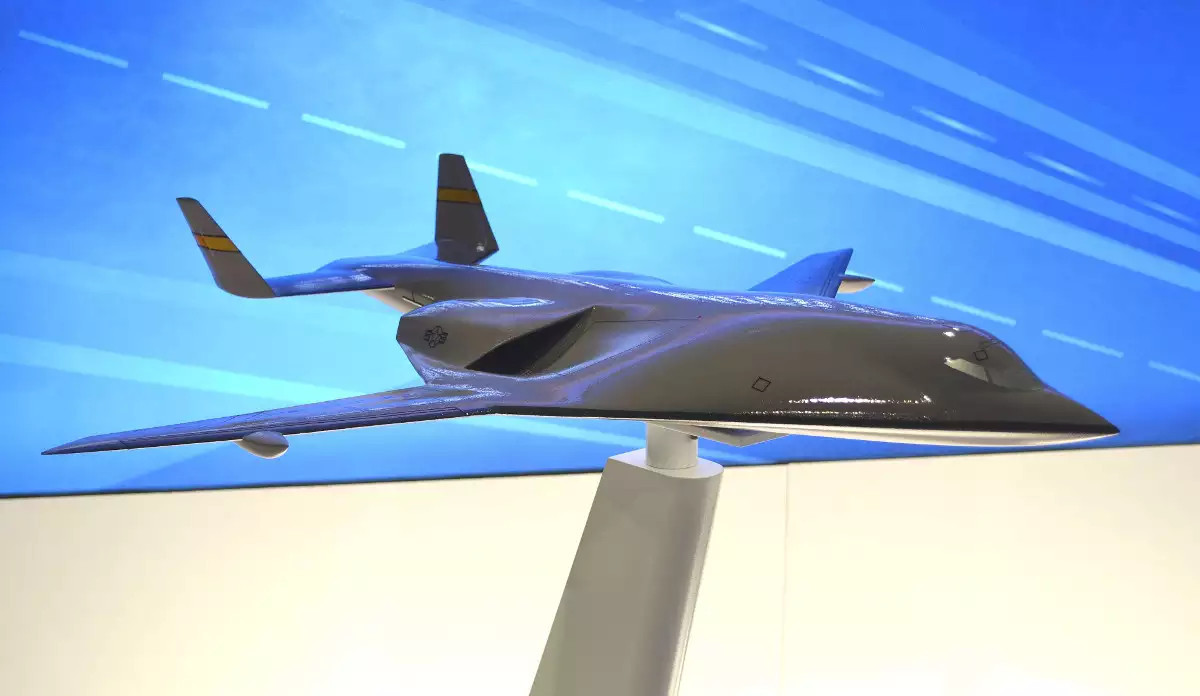

Lockheed Martin’s proposal was a stealthier hybrid or blended wing body design. This planform offers advantages in aerodynamic efficiency, which in turn improves fuel economy, as well as greater internal capacity in its wings for fuel. Clearly, the company’s ATT concept was also designed with stealth capability as a driving factor, when Boeing’s very much wasn’t.

Not long after it first emerged to the public in 2007, AMC-X experienced yet another name change, becoming the Advanced Joint Air Combat System (AJACS). As of March of that year, Alenia North America, Lockheed Martin, Piasecki Aircraft, and Voyager Aerospace had all indicated their intent to submit proposals.

Alenia North America was, at the time, competing for the Army-Air Force Joint Cargo Aircraft (JCA) light intra-theater airlifter program with its C-27J Spartan. Piasecki aircraft had been working with the Army and the Navy on high-speed compound helicopters.

Voyager Aerospace was a particularly interesting entrant in the context of the larger discussion about stealthy and short takeoff and landing capable transports. At the time, founder Dick Rutan, brother of Scaled Composites’ Burt Rutan, said the two of them had been working on an applicable twin-engine cargo aircraft design for more than 15 years, but offered no details, according to Flight magazine.

In 2007, this would have meant their supposed ongoing project began around 1992. This lines up with the time period shortly after Burt had submitted his proposals for the SOFTA program and right before the Senior Citizen special access program came to an end, both of which we covered in the first installment of this story.

The AMC-X/AJACS program did not have a clear requirement for a reduced radar cross-section. At the same time, Lockheed Martin’s submission, which was of the same general configuration as its proposal for the preceding ATT project, makes it clear that there was no prohibition against including stealth features. It is very likely that the Air Force left the requirements relatively vague and asked potential manufacturers to propose a design that they thought would be best suited to accomplishing the necessary mission sets. This is something we have seen in more recent U.S. military research and development efforts.

We do know that some senior Defense Department officials at the time publicly held the view that it wasn’t a necessity for future transport aircraft to be stealthy. “Low observable characteristics [stealth] are a useful attribute for aircraft supporting special operations forces, but are less likely to be of critical importance for other aerial maneuver operations since non-low observable aircraft can operate at altitudes above shoulder-fired anti-aircraft weapons, and suppression of enemy air defenses is assumed for more sophisticated systems,” a 2007 Defense Science Board report on vertical and short takeoff and landing capable aircraft said.

This has turned out to be a glaringly short-sighted assessment. Within a handful of years, anti-access and area-denial enemy strategies and the proliferation of very capable integrated air defense systems would become the primary focus of the Pentagon when it comes to preparing to fight future conflicts.

There is also always the possibility this public position may have been deliberate disinformation. Beyond that, relying on the suppression of enemy air defenses to clear a path to the objective would ruin the element of surprise that stealth transport aircraft would afford and the deniability of a clandestine insertion or extraction, which had and continues to be one of the core mission sets for a low-observable transport.

Regardless, while some elements of the U.S. military weren’t entirely convinced that stealthy features would be compatible with the AMC-X/AJACS aircraft, the Air Force was certainly looking to reduce the signatures of its future transport aircraft. “The Air Force is also looking for ‘balanced survivablility’ against an array of sensors – ‘infrared, radio-frequency, and human’,” FlightGlobal reported at the time, citing Carl Zuene of the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL).

Speed Agile

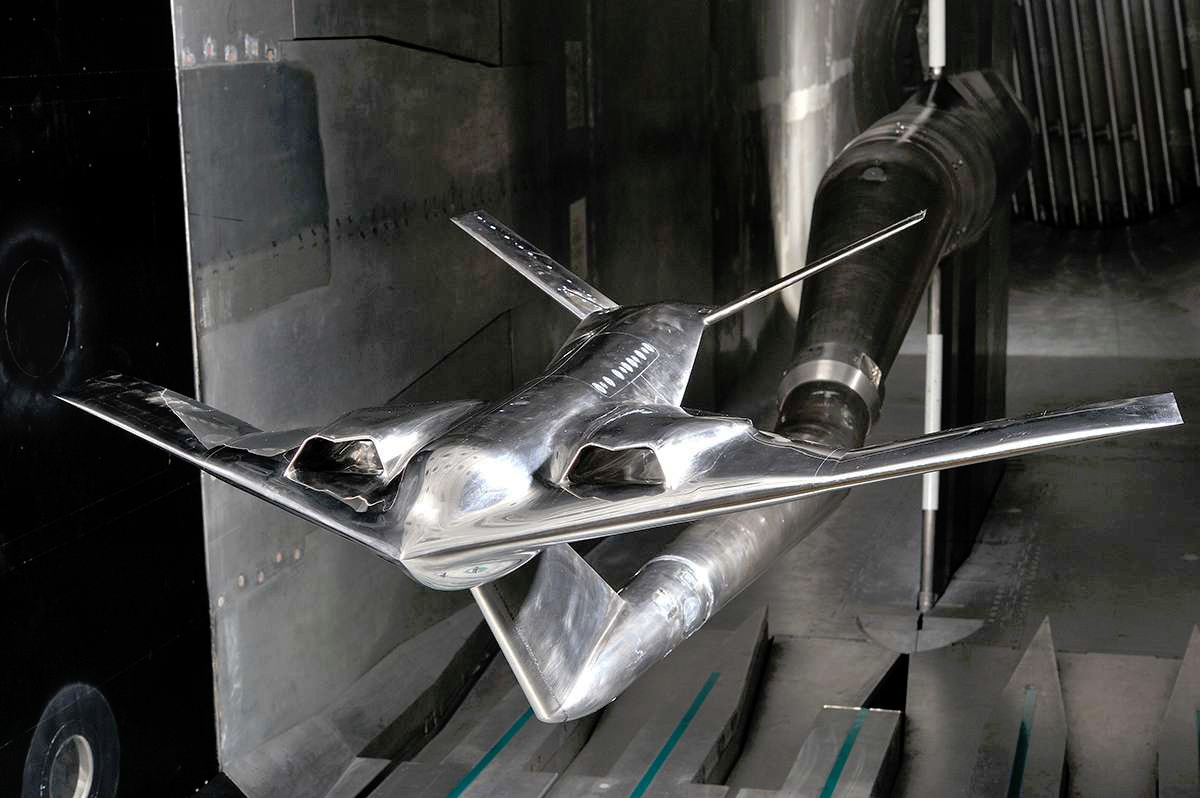

In 2007, Carl Zuene was the manager for another program called Speed Agile. This project was originally billed as supporting AJACS with low- and high-speed wind tunnel testing of the concept designs. Lockheed Martin and Boeing subsequently received contracts to build scale models of their proposed aircraft. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was also involved in this project.

Speed Agile ended up subsuming AJACS, which had hoped to produce a flying prototype by 2015. Here’s how the Air Force described what had become known as the Speed Agile Concept Demonstrator (SACD) in 2011:

“The Speed Agile Concept Demonstrator (SACD) concept is a four-engine, multi-mission aircraft that offers speed agility; operates routinely from short, improvised airfields; carries larger and heavier payloads; and employs precise and simple flight controls. The SACD’s high-efficiency STOL design incorporates a hybrid powered lift system. This lift system features a simplified mechanical design and low-drag integration. Together, these features greatly reduce both the vehicle weight and overall drag on the vehicle, resulting in greater efficiency and payload capacity than conventional powered lift systems. An aircraft employing Speed Agile technology could potentially operate from short, unprepared airfields. These benefits, coupled with the overall vehicle efficiency, could result in an extremely versatile aircraft capable of quickly and safely transporting equipment, supplies, and troops to remote areas.”

The models that Lockheed Martin and Boeing crafted were not entirely optimized for stealth, but did feature hybrid and blended wing body planforms that offered a reduced radar cross-section and some designs clearly had stealthy features. Speed Agile also leveraged separate work the Air Force and Lockheed Martin had done on developing advanced manufacturing processes for large composite material structures, such as the ones employed on stealth aircraft.

Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works advanced design bureau needed only 20 months to build the experimental X-55A Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft (ACCA) and put it into the air for its first flight. The company’s pioneering research for the Air Force, which you can read about in more detail here, would also have informed the company’s own submissions for programs such as Speed Agile.

Since 2011, Lockheed Martin has used designs related to their Speed Agile proposals as the basis for stealthy aerial refueling tanker concepts, which are still under development. It is possible that such a plane with generous payload capacity could be configured to perform various other combat support mission sets, including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, and electronic warfare support.

As of January 2019, there is no indication that Speed Agile has either come to an end or produced a flying prototype. Lockheed Martin has said in the past that it hopes to flight test one of its blended or hybrid wing body designs in the 2020s, although this could be under a separate initiative altogether.

Project IX

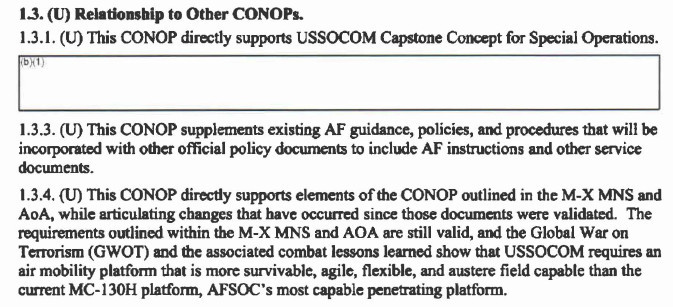

In parallel to Speed Agile, AFSOC secretly developed requirements for C-130-sized aircraft as part of what it called Project IX, also sometimes written as Project 9. In a redacted 2009 concept of operations (CONOP), which the author previously obtained via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the command describes the desired aircraft as such:

“The Project IX is a high-speed, medium-lift, long-range, short takeoff and landing (STOL), low observable (LO) platform to conduct special operations forces (SOF) mobility missions which exceed the capability of current SOF mobility platforms. Project IX will provide the capability to perform clandestine penetration into politically or militarily denied areas in two distinct mission areas: Strategic Special Operations and Supporting Joint Air/Joint SOF Missions in Denied Access Areas.

…

“The Project IX will provide significantly better aircraft performance than current AFSOC mobility platforms, including the C-130J, entail a smaller crew, require less logistical support, be able to operate from smaller, more austere airfields/locations, and provide significant interoperability improvements with other aircraft and command and control (C2) organizations. The Project IX will be reliable, survivable and able to conduct strategic clandestine SOF mobility infil/exfil/resupply in current and future denied access environments.

…

“Project IX supportability will initially rely heavily on contractor logistic support (CLS) because of the unique characteristics of the LO technologies. Service support, in terms of basing and security, will also be critical to transitioning Project IX from an advanced capability technology demonstrator (ACTD) program to a fully operational asset. There are lessons learned and precedents for such responsibility regarding other specialized aircraft (F-117, B-2, F-22, etc.), and Project IX will take full advantage of them.”

A number of general Air Force and U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) requirements informed the Project IX CONOP. The document also specifically makes reference to the aircraft outlined under the early 2000s’ M-X program and Air Force censors redacted another related CONOP in its entirety. It’s worth noting that the author’s inquiries to various public affairs offices and subsequent FOIA requests have yet to turn up evidence of any projects numbered one through eight.

The requirements for Project IX call for efforts to reduce the aircraft’s radar cross-section, as well as infrared, acoustic, and radio frequency signatures. “Regardless of altitude and the LO [low obsevable] and EW [electronic warfare] technologies incorporated into Project IX, visual and electronic detection of the aircraft may still be possible,” the CONOP warned.

Since it used the M-X concept as a baseline, Project IX’s desired combat radius was again set at more than 1,000 miles. The total required distance to take off or land was to be less than or equal to 1,500 feet. Any specific payload information that might have been present in the CONOP is redacted.

Not surprisingly, Project IX called for an aircraft with extensive communications capabilities and advanced electro-optical and infrared sensors to help with low-level flight and maneuvering on the ground, day-or-night, at austere locations. Particularly interesting was a desire for an electronic warfare system that could detect and classify threats in the air and on the ground and then instruct the aircraft to automatically make adjustments in the route to the target area to optimize survivability.

The crew would have the option of disabling the system’s automated functions “based upon the threat/mission circumstances.” “The EW [electronic warfare] suite should maximize receive only options from national intelligence sources to prevent compromise should aircraft be commandeered, while reducing weight and space,” the CONOP noted, as well.

This mix of stealth technology, electronic warfare countermeasures, and nap-of-the-earth flight capability would be essential for penetrating into a modern denied area deep inside an opponent’s home turf. Even the most specially configured MC-130 would almost certainly be far too vulnerable to operate in this kind of extremely high-risk environment.

The status of Project IX is unknown, but in 2010, Michael Vickers, then-Assistant Secretary for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict, a retired Army Special Forces soldier who had also previously been a paramilitary operations officer in the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Special Activities Division (SAD), seemed to allude to the program publicly. AFSOC’s stated goal was to field the aircraft sometime between 2019 and 2025 and this is a schedule the Air Force could still very well be intent on keeping.

Project IX in interesting because it seems like a realistic and detailed rationalization of decades of concepts that appear to have come and gone. In some ways, by the late 2000s, technology had also caught up with the tactical special operations concept to some degree, especially in terms of off-the-shelf subsystems, composite material science and manufacturing, and low-observable (stealth) design and applications. It stands as neither the most ambitious special operations low observable airlifter program nor the least, also making its feasibility much more probable.

Making the most out of what you already have

In 2013, AFSOC initiated what appears to be the most recent effort to investigate the possibility of developing an enhanced, short takeoff and landing capable transport capability that featured some signature reduction measures. The project, however, was far less ambitious than any of its predecessors, according to various additional documents the author has obtained via FOIA.

Known as Project 10, an apparent reference to having a relation to Project IX, the initiative primarily explored a raft of already available and potential upgrades for the C-130 aircraft. AFSOC did say that a second phase of the new project could “reenergize [the] SOF R&D [research and development] Community for next gen SOF mobility platform,” according to one January 2013 briefing, which name-checked a host of previous programs, including Credible Sport, MC-X, Speed Agile, and Project IX.

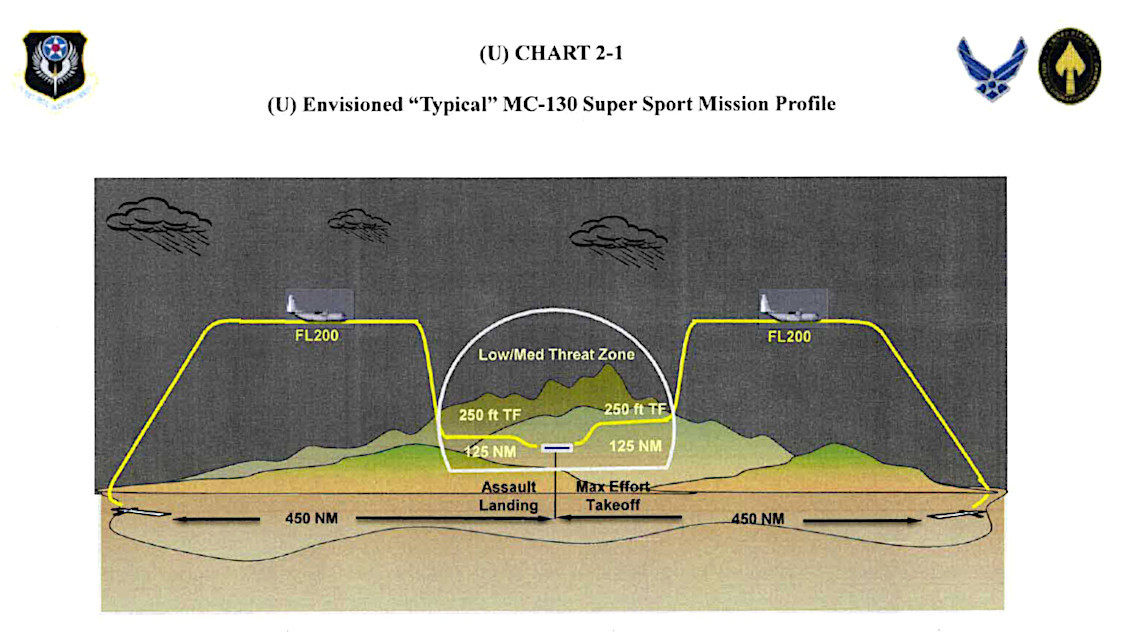

Project 10 was also known by the nicknames New Magic and Super Sport, the latter being a direct reference to Credible Sport. AFSOC described the proposed final product as the Low Signature Mobility Aircraft, as well. An April 2013 Capabilities Development Document (CDD) for the “Super Sport” outlines the basic need for such an aircraft as such:

“It is the nature of special operations that missions will be conducted against high-value, politically sensitive targets of critical importance to the nation. There will be occasions where these targets are located deep inside denied/sensitive territory and do not possess a landing zone suitable for current MC-130 aircraft. For these occasions, a Super Sport version of the MC-130 must be able to INFIL/EXFIL a special operations team and their equipment in the shortest time frame possible to conduct national-level, strategic missions. To meet dynamic mission requirements, the MC-130 Super Sport aircraft could be configured with the specialized equipment required to perform the majority of its MC-130 SOF Mobility missions to include airdrop/airland resupply, FARP [Forward Arming and Refueling Point], and MISO [Military Information Support Operations; also known as Psychological Operations].

“These Super Sport operations will be planned and conducted to very short landing zones in all environments to include high density altitude (i.e., high pressure altitude, high ambient temperature) with long-range insertion (with or without inflight refueling) direct from home station. In other situations, MC-130 Super Sport aircraft could self-deploy with a logistics support package to an interim staging base or a remote, sparsely equipped forward base. Support personnel would rapidly configure and equip the aircraft for its Super Sport configuration and aircrews could execute missions in minimal time with little external support.”

In the first real divergence from what was then three decades of increasingly firm requirements, Project 10 called for a plane capable of flying high-low-low-high mission profile across a combat radius of fewer than 520 miles – 450 nautical miles – with a payload of no more than 10 tons. The aircraft had to be able to take off and land within 2,000 feet.

The goal was to outline the modifications necessary to a MC-130H or J aircraft that would meet AFSOC’s needs and still be able to achieve initial operational capability (IOC) with within 30 months of issuing a contract. The Air Force defined IOC in this case as having three modified aircraft and five fully-trained aircrews, together with either an organic or contractor-operated support chain. The full fleet would consist of approximately 10 aircraft.

The possible Project 10 upgrades ranged from modifications to specific components to entire upgrade packages from Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and smaller firm Snow Aviation. AFSOC broke these options down into three categories: “low hanging fruit,” “more complex” upgrades, and “Far Term/Expensive” proposals.

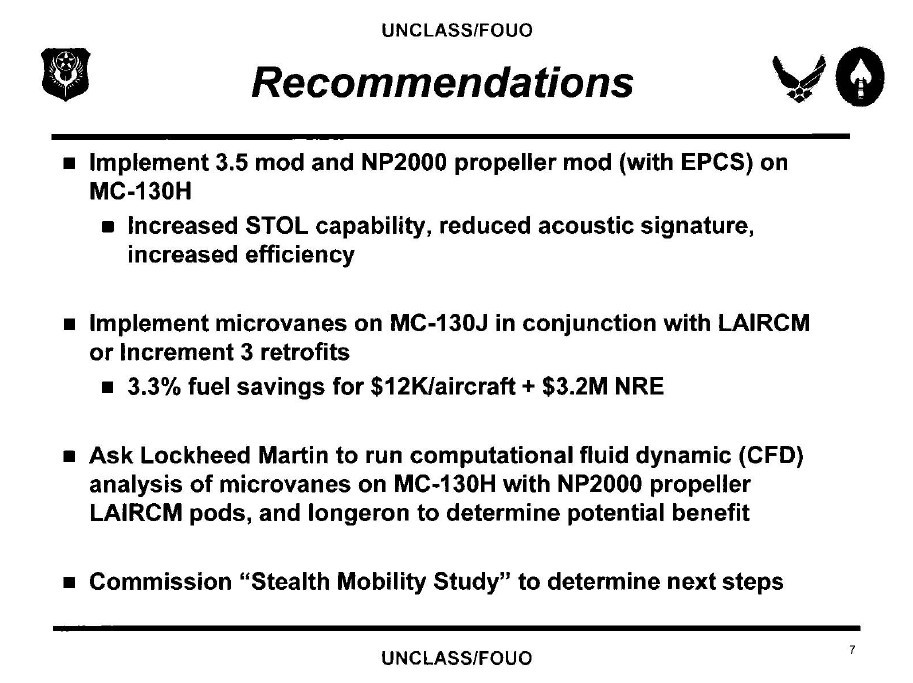

The first category included adding microvanes to various portions of the aircraft to improve airflow, installing eight-bladed Hamilton Sundstrand NP2000 propellers on all four engines, digital engine control systems for greater efficiency, a Lift Distribution Control System (LDCS), and simple weight reduction. A detailed description of the LDCS in documents obtained through FOIA is entirely redacted, but it reportedly offered improved fuel efficiency, greater payload capability, and long wing life all by itself. The microvanes offered greater fuel efficiency, as well as acoustic signature reduction.

The NP2000 propellers were the only individual proposal of any kind to offer fuel savings, improved flight and short takeoff and landing performance, increased reliability and reduced maintenance demands, as well as a reduced acoustic signature. Coupled with the engine modifications, these benefits only increased. The Air Force has considered adding these updates to standard C-130 airlifters, which you can read about in more detail here, but had still not moved ahead with the program in earnest as of January 2018.

AFSOC’s “low hanging fruit” category also included a modest upgrade package proposal from Lockheed Martin. This consisted of an engine upgrade with a new control system for optimal performance, improved flaps for added lift, and “speed break spoilers” to rapidly slow and stop the plane during landings. Available for the newer MC-130J Commando II only, this would give the aircraft the ability to takeoff within 1,400 feet and land inside 1,200 feet at sites at altitudes up to 4,000 feet and with a total aircraft gross weight of 110,200 pounds. A standard C-130J airlifter has a maximum takeoff weight of 155,000 pounds.

Options such as winglets, a system to blow compressed air over the wing surfaces to improve lift, extra internal fuel, and infrared, acoustic, and visual signature reductions were in the mid-tier category. There was also a second level of upgrade package from Lockheed Martin, which added further improved engines and flaps, and new propellers, which could work with either the MC-130H or MC-130J.

The winglets offered better fuel economy and improved short takeoff and landing performance. The Air Force has since tested the winglets on MC-130Js and standard C-130Js to further investigate the potential fuel savings, but has yet to make them a standard feature in either fleet.

The descriptions of the added fuel capacity are redacted entirely. The slide on the blown air system notes that the Japanese ShinMaywa US-2 four-engine amphibian has this feature and that the technology is well established, but that it’s unclear how much it might cost to integrate onto an MC-130.

The options to reduce the infrared signature are the most rudimentary, consisting of exhaust diverters and heat sinks. AFSOC also noted potential options to reduce propeller noise, engine vibration, and dampen the sound of the aircraft simply moving through the air, all of which would make it harder for an opponent to hear it coming, especially at night.

The visual signature reduction possibilities are especially fascinating. Project 10 noted advances in active camouflage, carbon nanotubes, and metamaterials, all of which could break up the outline of the aircraft or change its appearance in the visual light spectrum, making it difficult to identify, especially at extended ranges. Lastly, there was a proposal to use what are known as femtosecond lasers, which emit pulses of amplified light at extremely high speeds, to absorb visible light hitting the aircraft’s skin.

If these proposals worked, it could’ve allowed for the aircraft to have more options for operating in the daytime. The briefing specifically cites “lots of unsubstantiated claims on the internet, higher risk” as “cons” for these concepts, though. This is somewhat humorous, but it also seems indicative of just how unsubstantiated these applications were at the time of publishing.

The final collection of options under Project 10 consisted of major upgrade packages from Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Snow Aviation, as well as the possibility of adding stealthy features to the MC-130s. Northrop Grumman’s “C-130M” concept was listed as “Competition Sensitive” and censors blacked it out completely.

Lockheed Martin’s third tier upgrade and Snow Aviation’s plan both involved major modifications to the aircraft’s fuselage, wings, tail, and other surfaces, primarily to improve short takeoff and landing capability. Snow Aviation’s proposal also had a significant increased fuel capacity, in both new internal and wingtip tanks, for greater range. In addition, it featured employed the NP2000 propeller, giving it the acoustic signature reduction benefit.

As noted, some of these modifications have worked their way into the Air Force’s general modernization plans for the C-130. So far, there isn’t any indication that AFSOC has proceeded in any significant way with the plans it outlined in Project 10.

“At this time, AFSOC is not actively engaged in development of new requirements for a short takeoff and landing variant of the MC-130,” a public affairs officer for the command told the author in 2015. “The last analysis was completed in April 2013, and the documents were never validated as formal AFSOC requirements.”

In 2013, the Project 10 managers had recommended exploring some of the smaller upgrades, such as the NP2000 propellers and microvanes, in the near term. “Commission ‘Stealth Mobility Study’ to determine next steps,” was their final suggestion.

Overall, Project 10’s near-term goals seem to be a logical path toward getting the most out of the C-130 for low and medium threat missions. Such an aircraft could even assist a Project IX aircraft stage at remote locales along the edges of highly contested territory. So with Project IX and Project 10, we are talking about two disparate capabilities and mission sets that are more complimentary of each other than anything else.

Additional evidence?

With such persistent, stable requirements, spanning four decades and at least a dozen known, named programs, and more we surely still don’t know of, it is hard to imagine that one or more them did not actually produce flying prototypes or even an operational capability. The alternative is that the U.S. military, and the Air Force, in particular, has run all of these projects and design studies on various assault transport aircraft with vertical and/or short takeoff and landing capabilities and stealthy features for nearly 40 years, at the cost of many millions of dollars at least, without any tangible results whatsoever. If indeed this is the case, a seemingly large and very well identified capability gap has remained unfulfilled.

There have also been repeated reports and alleged sightings of aircraft that fit the description of an advanced, stealthy transport plane, including the various claims about the Senior Citizen program. The existence of such an aircraft could also offer an explanation for the sightings of the so-called “flying Doritos” in the skies over Texas in 2014. We have also received a number of tips about stealth transport aircraft of a particular description working in the Arctic region for some time now, and that is not counting all the other reported sightings of advanced aircraft over the previous three-plus decades.

Continued technological developments in stealth and vertical and short takeoff and landing capabilities didn’t come to a halt, either. Lockheed Martin’s Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) Advanced Reconnaissance Insertion Organic Unmanned System program, or VARIOUS, among many others, shows that companies are still leveraging their past work and publicly applying it to contemporary concepts. The F-35B alone is a remarkable showcase of operational STOVL technology and its powerplant components alone could be a springboard for stealthy special operations transport capabilities.

On top of that, there is a significant amount of tertiary information that suggests this capability is available, at least in small numbers or in a quasi-experimental state. The biggest indicator is the proven existence of a far less capable, but still stealthy vertical takeoff and landing capable special operations transport aircraft.

The aircraft in question are the Stealth Black Hawks that SOCOM employed during the raid on Al Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan on May 2, 2011. These aircraft represent a more survivable counterpart to other special operations rotorcraft, such as the Army’s MH-60M Black Hawks. The MH-60M, and earlier special operations specific MH-60s, themselves reflect a lower tier of a more conventional clandestine insertion and extraction capability. Even if the Stealth Hawks only existed in tiny numbers and even in an experimental form, they did indeed exist even though there was far less proof – as in next to none – of such a concept being realized compared to a stealth fixed-wing tactical transport.

Then there is the V-22 Osprey, which gave special operations forces a revolutionary platform that allows them to rapidly deploy over longer ranges than a standard helicopter, but without giving up the ability to infiltrate and exfiltrate vertically into constrained areas. Air Force Special Operations Command’s CV-22B Ospreys possess the speed, range, electronic warfare and self-protection defenses, situational awareness and communications capabilities, and nap-of-the-earth flight abilities that collectively allow it to penetrate some enemy defenses in order to carry out risky special operations missions. In fact, for shorter-range missions with more limited payloads, this aircraft addressed many of the operational needs that the Credible Sport C-130 had sought to fill back in the early 1980s.

But the Osprey is not a low-observable asset by any means and it still has limited unrefueled range. In this day and age of anti-access tactics and dense integrated air defenses, the CV-22B would be hard pressed to carry out deep insertion and extraction of special operations forces in high-risk, anti-access environments and especially against peer state foes.

Doing anything like this clandestinely, without relying on nearby support assets, would be all but impossible even according to the Pentagon’s own decades-old white paper that we discussed earlier. Well before the V-22 was even in service, the Air Force was already of the view that the Osprey would not obviate the requirement for a separate stealth special operations platform to operate over long-ranges in higher risk environments.

“The V-22 can only be utilized in [a] low intensity environment and does not meet the postulated range requirements,” according to a 1987 memo from Air Force’s Aerospace Sustainment Directorate, then part of Air Force Materiel Command, which Reddit user u/aclockworkgreen1 posted online in 2014. “All indications are that the V-22 will not, in fact, fulfill the requirements for stealth and range.”

At that time, the Air Force warned that if other services, such as the Army and the Navy, abandoned the V-22, it might similarly withdraw from the program. In that case, the proposed course of action was to “take the lead in the mid 1990s with a more capable aircraft.”

Further evidence that some sort of a stealthy special operations transport exists is out there, as well. Journalist and author Sean Naylor’s Relentless Strike: The Secret History Of Joint Special Operations Command mentions that in 2011 the raiding force considered parachuting into Osama Bin Laden’s compound, but does not say how a transport aircraft would have been able to successfully deliver the force to the drop zone.

The employment of the Stealth Hawks initially indicated that there were major concerns about the Pakistani military detecting the infiltrating aircraft and engaging them or Al Qaeda sympathizers within Pakistan’s security forces taking any information provided to the government in advance of the raid and alerting Bin Laden. We now know that this was all true and more.

There was a high probability that if an aircraft was detected, Pakistan’s Air Force, that sits on high alert due to tensions with India, would have tried to shoot it down. At the very least, such a situation would have ended in an aerial standoff between U.S. and Pakistani fighters.

With all this in mind, flying a lumbering MC-130 or CV-22s nearly over the major Pakistani military base in Abbottabad seems extremely unlikely as far as options go. Powered parachutes, wingsuits, and high-altitude high-opening parachuting techniques may have enabled a stand-off insertion from a non-stealthy platform, but they would have still required a cargo plane to fly deep into highly monitored Pakistani airspace at higher altitudes where they are extremely vulnerable to detection.

Then there is the whole issue with how do you get the teams out without accepting too much up-front risk if they were to parachute in from an asset that couldn’t also recover them. During the raid, the special operations MH-47 Chinooks didn’t push into the target area until the very end of the operation as part of a contingency plan should a Stealth Hawk crash, which one did. If that aircraft hadn’t gone down, the Stealth Hawks would have exfiltrated the teams and we would never have known a stealthy Black Hawk variant even exists.

In the end, U.S. Navy Admiral William McRaven, then head Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) reportedly axed the plan, but only apparently because of the danger of the SEALs getting their parachutes tangled in power and phone lines in the area, according to Naylor’s book. So once again, the big question here is what platform was really being considered for this option? With what we know, a non-stealthy one seems unlikely.

The existence of the RQ-170 Sentinel penetrating surveillance drone mentioned at the start of this piece is also an interesting example to comprehend. It is another capability requirement that emerged in the early 1980s, in its case in the form of Northrop’s Tacit Blue, but remained unsatisfied, at least publically in an operational state, until the appearance of the RQ-170 at Kandahar Airfield in Afghanistan back in 2007. You can read all about the RQ-170’s direct lineage to Tacit Blue here, but suffice it to say that if it took nearly 30 years and many steps to realize that game-changing capability set, there is nothing to say that the same wasn’t true of for a stealthy special operations tactical transport.

Maybe the most interesting potential tell that at least some type of highly secretive special operations transport exists is the fact that those that are tasked with the aerial refueling of special operations aircraft on the most complex missions they execute cannot speak of every type of aircraft they work with. All the other known types in the U.S. military’s inventory that would require the aerial refueler’s unique skills seem to be accounted for, but there are still “others” that remain undisclosed and that individuals associated with the Special Operations Aerial Refueling program cannot discuss. We also know that elements of the tanker community have provided gas to secret exotic aircraft operating over war zones and over the U.S. from time to time.

Who would fly them?

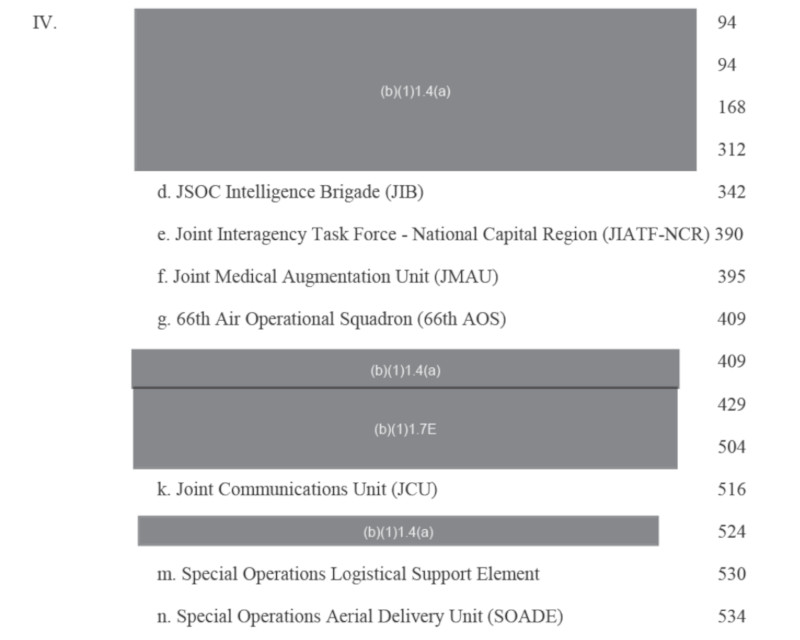

In the black world of super-secret U.S. military aviation units, which we at The War Zone have previously examined in detail based on what information is publicly available, there are prime candidates for who might operate such an aircraft. The Air Force’s 66th Air Operations Squadron, about which virtually nothing is known, is often simply said to fly C-130s.

Another secretive unit, the 427th Special Operations Squadron, appears to own the covert and clandestine infiltration and exfiltration mission in low-threat environments, using a fleet of civilian-styled turboprop light utility and small transport aircraft.

The Army’s Flight Concepts Division (FCD), now known as the Aviation Technology Office (ATO), could also operate the stealth aircraft. This unit, by most accounts, was also the unit in charge of the Stealth Hawks. Before the Bin Laden raid, FCD/ATO already had a long history conducting clandestine missions and working with the most elite of America’s special operations forces, as well as the CIA.

Though typically associated with helicopters, this organization has reportedly acquired a number of C-27Js, an aircraft that sits between the CV-22 and the C-130 in terms of payload, range, and STOL capabilities. The Air Force mothballed these aircraft in 2012, the result of an entirely separate saga, and subsequently began divesting them to other U.S. government entities, including the Army.

We know that the U.S. Army Special Operations Command’s (USASOC) Flight Battalion has acquired some of them. This unit is ostensibly a training and non-combat support unit that provides organic airlift and airdrop capabilities during drills, including Robin Sage, the capstone exercise for candidates hoping to become Army Special Forces soldiers.

The Aviation Applied Technology Directorate (AATD) may also have some for research and development activities. This office is responsible for various advanced, but generally public Army aviation research and development efforts.

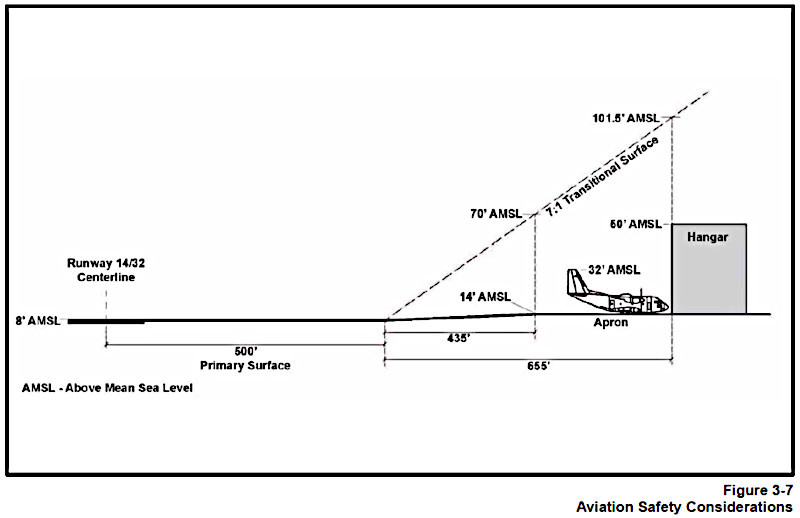

But it is possible that the AATD may share its fleet to some degree with that of the top-secret FCD/ATO. Both organizations are situated at Felker Army Airfield at Fort Eustis, Virginia, but the latter operates under extremely tight security out of a highly secure hangar at the airfield.

FCD/ATO is slated to get a new, larger hangar, as well as associated facilities, in a remote area near the airfield in the coming years. Concept art and dimensional diagrams both feature the C-27J prominently, reinforcing the significance of those aircraft, and/or ones of similar size, to the unit’s operations.

The Spartans may serve as a cover and training surrogate for a similarly sized clandestine transport aircraft. There is definitely a precedent for this, with the Air Force using A-7 Corsair II combat jets and T-38 Talon jet trainers to help hide the F-117 stealth combat jet program during the 1980s.

It is even possible that a C-27J-sized stealth transport aircraft resides under the FCD/ATO’s purview and a C-130-sized stealth aircraft does the same under the control of the 66th. This would again reflect the multiple tiers of capabilities that the Pentagon has been describing in its stealthy transport requirements for years now. Both of these units also work closely together in general under the broader umbrella of Joint Special Operations Command’s Aviation Tactics Evaluation Group (AVTEG).

The parent services might have limited knowledge and control over any stealth transports that might exist assigned to units under the AVTEG umbrella, further obfuscating the true “owner” of these planes. We know that there are still units assigned or attached to JSOC the existence of which remains classified.

A stealth transport program could very well be an interagency affair, as well. The CIA, in particular, has a long-standing relationship with advanced and novel aircraft programs and has a regular need for covert and clandestine means of inserting and extracting personnel in denied areas.

There is also a history of the Agency working with the U.S. military, directly or indirectly, and taking part in top-secret interagency operations that might require this kind of stealthy transport capability. Operators from the CIA’s Special Activities Division were notably involved in the Bin Laden raid, for instance.

If the aircraft only exist in tiny numbers and in experimental form, then it may be the case that no unit formally flies them in an operational capacity, at least not outside of unique circumstances.

So, where are they?

If any of these planes do indeed exist, where is the U.S. military, or its interagency partners, keeping them? An advanced special operations transport in the C-27 size class, a fleet of which would likely exist only in small numbers if they do indeed exist, would be relatively easy to conceal without the need for large specialized hangars and associated facilities that would stand out and draw attention. A small fleet of C-130-sized planes would be more difficult to keep hidden from the public eye based on already available facilities.

The secretive Tonopah Test Range (TTR) Airport would be one ideal home for these aircraft. AFSOC and the special operations community, in general, have been active at the field over the last decade and has used it to carry out key tests and training. Area 51 and a small handful of other secret test sites would also be possibilities, but only if the aircraft are still in testing in tiny numbers. The U.S. military might look to utilize more public bases, but only in remote areas, such as Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska or Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico for operational home-basing.

It’s important to note that if the fleet of these aircraft is truly minuscule in size, and it likely is, with a dozen or less airframes on hand, the majority of these aircraft would likely spend much of their lives forward deployed to major hotspots. Keeping a couple airframes stationed in Europe, the Middle East, and the Pacific region, near foes such as Russia, Iran, North Korea, and even China, would require a standing training cadre of just a couple airframes back home in the United States for training and tactics development. If this is the case, even a C-130 sized stealth transport would be quite easy to hide at a variety of locations, with the aircraft only venturing out at night for training and actual operations. If the airframe doesn’t even require a long runway, the potential basing locations increase dramatically as well.

There is also, of course, the possibility that the U.S. military continues to lack this capability in any form. “The requirements outlined within the M-X MNS [Mission Needs Statement] and AOA [Analysis of Alternatives] are still valid, and the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) and the associated combat lessons learned show that USSOCOM requires an air mobility platform that is more survivable, agile, flexible, and austere field capable than the current MC-130H platform, AFSOC’s most capable penetrating platform,” AFSOC explained in its Project IX Concept of Operations (CONOP).

The Project 10 documentation similarly used phrasing that suggested there was no actual applicable aircraft within the U.S. military. “Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) currently does not possess the capability to execute an enhanced short takeoff and landing (STOL) mission with a significant amount of cargo or personnel,” the command said bluntly in the 2013 Super Sport Capabilities Development Document (CDD).

It’s interesting to note that they mention “a significant amount of cargo or personnel.” Smaller stealth penetrating special operations concepts have had less lifting capacity than a CV-22 Osprey, so this statement does not preclude the existence of such an aircraft. In addition, a smaller type capable of delivering and extracting a squad of operators would be far less expensive and risky of a program than one that mirrors the capability of a C-130.

None of this addresses the possibility that one or even multiple concepts made it to the flight demonstration phase, but never proceeded past that point in a larger operational sense. In fact, there could be multiple approaches to various aspects of this unique mission set in storage or even buried out at Area 51.

But it’s also worth remembering that the Project IX CONOP was only ever classified “Secret” and the Super Sport CDD was always unclassified. Though units such as the 66th Air Operations Squadron and the Aviation Technology Office technically belong to their parent services, they operate almost exclusively under the direction of JSOC and in highly compartmentalized spaces at levels of classification well above Secret.

So, it is not hard to imagine that the individuals drafting the documents in question were unaware of what was or is still occurring in the “black” realm. As noted throughout this two-part story, the ever-lengthening parade of publicly acknowledged programs could easily serve as a cover for unacknowledged active developments or even operational activities. We at The War Zone have previously explored similar relationships within some of the most secretive ends of the Air Force’s unmanned aviation community.

After 40 years of programs, all of the sudden having the requirement go unaddressed in any way would also be a big indicator to foreign adversaries that the capability exists and the requirement has been satisfied. So this long slog of perpetual initiatives to provide an advanced low-observable special operations transport could now serve as a necessary cover for a capability that was indeed realized some time ago.

Furthermore, the demand for stealthy, or at least stealthier combat support aircraft, such as aerial refueling tankers and transports, is rapidly becoming a necessity for conventional units as the air defense capabilities of potential opponents continue to improve. Why would the U.S. military’s most elite units have ignored this reality, on top of their own standing requirements, for so long?

“The Super Sport program is not new in concept nor requirement; the need to provide SOF support any time, any place can be directly traced to the Credible Sport programs of the 1980s,” AFSOC declared in 2013. “The Super Sport program is the natural evolution in AFSOCs desire to provide flexible solutions to SOF requirements.”

With this in mind, if the U.S. military does indeed still lack this capability after all these years and piles of money spent, it would seem to be an outrageous oversight.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com