It may not be glamorous, but the largely misunderstood Grumman E-2 Hawkeye is arguably the most important aircraft deployed aboard America’s supercarriers. It acts as the high-flying eyes of the carrier strike group and provides critical air traffic control and combat management for carrier air wing aircraft, as well as communications relay and other functions. Retired Naval Flight Officer Craig “Slim” Picken worked in the inhospitable confines of the Hawkeye’s fuselage during one of the most interesting times in modern military history, rattling off intercept orders to missile-laden Tomcats and coordinating the ballet of U.S. Navy carrier-borne tactical aircraft as they plied their deadly trade over Iraq.

So come with us as we follow “Slim” into the tight confines of the Hawkeye’s belly, take a seat alongside him in front of one of the glowing radar consoles and get ready to get to catapult off on a voyage that will make you understand the Navy’s vaunted airborne early warning and control plane like never before.

The Reality

Had Top Gun filmmakers been accurate in their account, the opening scene with Maverick would have been handled completely differently.

Under the powerful radar and watchful eyes of its crew, the E-2 Hawkeye, flying at 27,000 feet, would have spotted the incoming “bogeys” from more than 150 miles away. Maverick’s Tomcat would have been quarterbacked with a real-time picture, accompanied with data-link updates and a familiar voice helping with the “target sorts.”

A surprise 2nd bogey? Not a chance!

Cougar wouldn’t have been jumped and would have kept his wings to fight another day.

Today, the entire dogfight might have be quarterbacked by the E-2 without its controllers even saying a word.

But Top Gun was a movie about fighter pilots, not the cast working tirelessly behind the scenes to support them. The E-2 Hawkeye is like the Offensive Coordinator on an NFL team. He sits high up near the press box and well out of sight from the crowd, but very much in the game. His knowledge, God’s eye view, situational awareness, headset, and microphone are his weapons.

Yes, he is out of sight, but make no mistake who is calling the offensive plays.

Flying Quarterback

Despite its ugly looks and slow and lumbering airframe, the Hawkeye is the most sophisticated airplane on the aircraft carrier flight deck. Its mission is Airborne Early Warning (AEW) and battle management.

Its long-range AN/APS-139/145 radar is capable of spotting and tracking thousands of contacts from hundreds of miles away. Coupled with its complex radio suite that provides secure and satellite communications to other aircraft, surface ships and ground forces, as well as its advanced IFF (Identify Friend or Foe) capability and high-speed data links, the airplane is the go-to tool for battle management and control.

In fact, the air wing, and the (carrier) battle group to some extent, could not function without it.

If you doubt my word, just ask the British Navy regarding their experience in the Falklands 35 years ago, which occurred without the help of Airborne Early Warning.

Oh, and don’t let the E-2’s size fool you. Its five-person crew, two Naval Aviators (pilots) and three Naval Flight Officers (NFOs, the radar operators), are highly trained and skilled, and the reality is that the new E-2D Advanced Hawkeye can do everything its larger cousin, the E-3 Sentry AWACS, can do, but with a whopping 20 fewer people onboard.

The Airplane

I’m not sure how the Grumman engineers came to develop the E-2, because it’s an engineering marvel that got beaten by an ugly stick. Its design also overcomes several extraordinary challenges that needed to be addressed for the airplane to meet its unique mission requirements.

First, the 24-foot wide radar dish is neutral in flight. It provides as much aerodynamic lift as it does parasitic drag.

Second, the engines and propellers provide enough power to allow for engine-out climb capability should the Hawkeye lose an engine mid cat-stroke (catapult launch). The T-56 engines on the E-2C each provided 4,950 shaft horsepower and spin a huge propeller at 1,100 rpm. On the newer versions, the horsepower has been increased to 5,100 horsepower.

Third, both propellers spin counter-clockwise creating a lot of yaw instability, thus, the reason for the four vertical stabilizers and three rudders. The propellers are made of composite material to eliminate interference with the radar’s performance.

Fourth, big airframe needed to hold all the equipment must fit on an aircraft carrier deck. This means that the 80-foot wingspan has to fold so that the airplane can be neatly tucked away.

Like every airplane, the design is a compromise. It does some things well, others not so much. It will never be fast. It will never be pretty. And, because it’s a turboprop it’s limited to about a 28,000-foot ceiling, above which the props become inefficient.

It’s a beast of an airplane that weighs in at more than 26 tons.

The Radar

Located inside the 24-foot dorsally-mounted dish is the AN/APS-139/145 UHF-band radar that can track targets from well over 200 miles away. The original Hawkeye mission was Airborne Early Warning (AEW)—an airborne platform that could protect the aircraft carrier and battle group assets from Russian bombers carrying long-range missiles, as well as enemy ships and other threats, which it did well.

To enhance its effectiveness as a battle manager, the Hawkeye’s radar picture can be data-linked to multiple destroyers and cruisers located hundreds of miles away, to create a monstrous, virtually impenetrable air defense posture. When coupled with the highly effective Aegis Combat System’s SPY-1 radars found on guided missile cruisers or destroyers, that posture can extend well over 500 nautical miles.

Via Link 4 and Link 16 data links, that same picture can also be transmitted directly into the cockpit of fighter and attack aircraft. Coordinated air intercepts can be done with literally no verbal communications.

But the radar was challenged in that its UHF frequency ranges were optimized for maritime use and its early mission computers were both heavy and, at least by today’s standards, horrifically obsolete. Thus, it was not the most effective platform to detect low flying threats over land or in a high clutter radar environment.

With new radar, systems, and computers, the new E-2D, however, provides game-changing performance in any environment.

The Back-End

The E-2 has three Naval Flight Officers (NFOs) in the back:

RO – Radar Operator. Responsible for maintaining the radar, data-links, and passive detection systems. Will also have aircraft under his or her control. The RO sits in the most forward seat and is often the most junior aircrew. New NFOs in the squadron are only qualified in this seat until deemed ready to move to another.

ACO – Air Control Officer. Guy controlling most of the air wing assets. May have up to 20 airplanes under his control. He’s the furthest aft and stays very busy.

CICO – Combat Information Center Officer. The “Mission Commander” who is usually the most senior person. He’s got the “big picture” and is talking to everyone. To become a CICO is a year or more long process and the qualification is blessed by the other squadron CICOs and the squadron Commanding Officer. As a RO or ACO your every move is monitored and graded. If you can’t cut it in both of those seats, you don’t become a CICO and your Navy career is ruined.

With Desert Storm under my belt, I earned the CICO designation in a fast 10 months.

No matter what seat one is in, each officer is staring into a radar screen and tracking targets.

Before each launch, the CICO does rounds around the ship and meets with the fighter and attack squadrons and the ship’s Combat Information Center to get the overall “big picture.” If large combat missions were occurring, he’d sit in the briefing and discuss the plan.

Additionally, the E-2 crew briefs the flight two hours before launch and mans-up the airplane an hour before.

It takes that long to do pre-flights and get the radar warmed up. Typically, the Hawkeye is the first to launch and the last to land. Not because everyone deems it special, but because its size makes it the most difficult aircraft to maneuver on the flight deck.

This means a four to five-hour flight is really an 8 or 9 hour day when factoring in the brief, flight, and debrief.

The Hawkeye-Tomcat Team

For three decades, the Hawkeye-Tomcat combination was an intimidating duo that could pack a hell of a punch. The Hawkeye’s long-range radar coordinating the Tomcat’s payload of Sidewinder, Sparrow, and, most notably, AIM-54 Phoenix radar-guided missiles gave carrier air wings an anti-air capability unmatched anywhere in the world.

The AIM-54 Phoenix proved the most fearsome as it allowed the F-14 to engage multiple targets simultaneously from long distances. Had the Russians launched multiple Tu-95 Bear, Tu-16 Badger, or Tu-22M Backfire bombers to attack the battlegroup, they would have surely been detected by the carrier’s Hawkeye and shot down by a Tomcat from distances over 100 nautical miles away.

Until the demise of the USSR in 1991, the Russians constantly practiced their attacks on the aircraft carrier, and the air wings continually practiced their defensive profiles. It was a never-ending cat and mouse game that both sides got very good at playing

There were two occasions where my crews tracked Russian Bears – once while transiting out of Subic Bay the Philippines in early 1991. The second time we launched off a 30 minute alert in the Northern Pacific when the Bears decided to visit us from their home in the Kamchatka Peninsula. Each time they were intercepted by our Tomcat brethren, with a Phoenix under their bellies.

“No Respect!”

The E-2 is a bit like Rodney Dangerfield. It rarely gets the respect it deserves.

This fact was pointedly made at Fightertown USA—Naval Air Station Miramar—by one of our squadron pilots, Westin “Son of Sam” (SOS) Richardson, or “Sauce” for short.

Upon landing one afternoon, SOS promptly radioed “Tower, Sun King is clear of the duty. Taxi to the Leper Colony.”

At the time, all the Hawkeyes were quartered in Hangar 6, at the very west end of the airfield, about as far away from TOPGUN as they could possibly get.

Judging from the hysterical laughter coming from the tower, they fully understood our intent!

Throughout my Navy career, never did a reporter or news crew ask us what we did or the importance of the mission. If we took an airplane to an airshow, we lived a lonely existence.

When CNN came onboard the USS Ranger, and they occasionally did, they just wanted film the glamorous Tomcats launching in full afterburner. “TOP GUN!”

If anyone ever asked me if I was TOP GUN, my answer was “no, I’m more like the anonymous Key Grip from the movie. I just make sure the shit shows up.”

The NFOs in the back, who do their jobs in a darkened tube, are often referred to as “Moles.” I’m not sure anyone joins the Navy to become a “Mole.”

Respect Is Earned

I say that “respect is earned” in a somewhat tongue-in-cheek manner. Within my Air Wing (CVW-2) we held a unique standing. We never got the glory or attention that the fighter and attack pilots got, but we were held in high esteem on the pecking order.

Everyone, at some point, was going to ask for our help.

As a squadron, we were a group of 25 highly competitive, disciplined Naval Aviators and Naval Flight Officers led by squadron commanders who drove us hard.

From the day you arrived on the squadron quarterdeck you put on your flak jacket. Any sense of weakness you showed, at any time, was exploited in every manner possible. The ready room atmosphere could be brutal!

We carried this attitude with us every day. Our Air Wing brethren saw we were hard playing, hardworking, competitive officers and aviators, which carried a lot of weight.

After a while, the VAW-116 Sun Kings became known on the west coast as the “Fun Kings.”

A Unique Community

Upon arrival to the squadron on you realized that nobody really chose to be there.

In my squadron, VAW-116, I don’t think one Junior Officer signed up to fly an ugly lumbering turboprop. The pilots were top players in flight school who got drafted into the Hawkeye pipeline. Most were frustrated fighter or attack wannabes. The NFOs in the back were all the same.

Nonetheless, almost all the pilots were some of the best you’d ever find—outstanding “ball flyers,” outstanding in helping out with the mission when needed, and outstanding in an emergency when one arose.

“Cowpie” was a professional rodeo bull rider before joining the Navy. He would entertain us with his hilarious stories about driving his van across West Texas and Oklahoma, going from rodeo to rodeo.

Another, “Gordo”, learned to fly gliders in his youth. Today, he is a world-champion glider pilot. Cowpie went on to become the Commodore of the entire west coast E-2 Hawkeye and C-2 Greyhound wing.

The NFOs were often brilliant. Intimidatingly so.

Several squadron mates who didn’t make the Navy a career have gone on to become highly successful CEOs, CFOs, lawyers, and entrepreneurs. Others who did make it a career went on to become aircraft carrier commanders, air wing commanders and admirals.

Getting Respect

Getting respect within the air wing is not a given. It’s often hard work and to get it, many of us became fully integrated with our fighter and attack brethren.

The respect earning phase started during “work-up” cycles—the various at-sea training periods when we’d all learn how to work together. For junior A-6 or F-14 crews, it was the first time ever they’d work alongside a Hawkeye.

During these cycles, several of our officers would be in another squadron’s ready room. They could be bullshitting on a friendly basis or deep in the manual of an F-14 or A-6. Or, we’d simply connect in the ship gym or over a meal in the wardroom.

It was the little gestures of “we’ve got your back” that solidified the relationship between the E-2 crews and everyone else. Trust is monumental.

As an example, during our transit to Desert Storm, our CAG (the Carrier Air Wing Commander) became obsessed that coded Mode 4 IFF (Identify Friend or Foe) transponder worked in every airplane for every mission.

If we were going to fly combat, he wanted to ensure no friendly-on-friendly engagements occurred.

To prove his point, any aircraft that launched without operable Mode 4 was sent to the “penalty box”—an area 20,000 feet directly above the carrier—and forced to hold in a pattern until the end of the cycle. Usually 90 minutes or so.

It sucked and the crews hated it.

After each airplane launched, its IFF was interrogated by the ship looking for positive Mode 4 response. If it was “sweet,” the aircraft could proceed to its mission. If “sour,” to the “box” they went.

As the airborne commander, however, we could override the ship. We had an IFF interrogator too, and who was to say we were wrong?

“Strike, King has Wolf 101 sweet, sweet. 101, head 090 to the tanker, Angels 20.”

I’d then follow up the call a few minutes later on the tanker frequency, “Wolf, get your gadget fixed.”

They got it and appreciated the gesture.

Yep, We Got Booze

During my squadron tenure, I was dating a Delta Airlines flight attendant and every so often I’d get a care package complete with a few dozen mini-bottles of vodka.

Because alcohol is strictly forbidden on the ship, we’d keep it stashed in a space under the bottom rack in our stateroom, which I shared with two other officers.

The empties? We’d take them to the usually empty ship’s forecastle and drop them into the ocean via the anchor-chain openings.

No, we never got crazy, but it was something to take the edge off after a long day or extended period at sea. We’d mix the vodka with “bug juice” taken from the officer’s mess and, sometimes, have a small gathering with the crews from VF-1 who lived along the same passageway.

One night, our CO banged on our door, which sent us scrambling to hide the evidence.

We let him in and we could tell he’d had a really bad day.

“I need a drink” he proclaimed.

With amused looks on our faces we responded, “sorry, Skipper, wrong place…”

“Fuck you! I need a drink.”

We gave him two bottles.

Nothing was ever spoken of it. It was just another trust-building exercise.

It Isn’t Flying First Class

The Hawkeye is a very uncomfortable airplane.

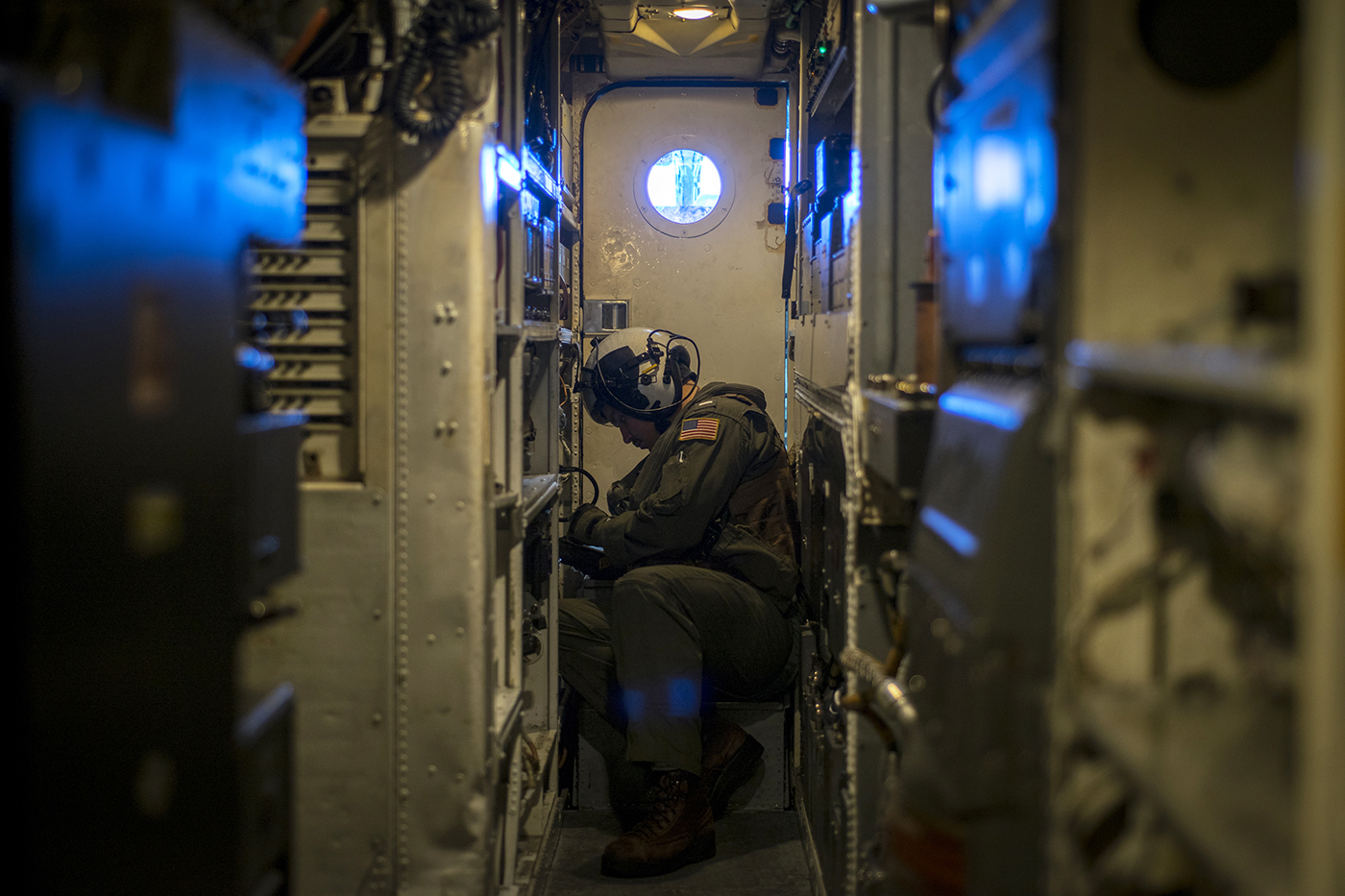

The three Naval Flight Officers (NFO) in the back sit sideways for four-plus hours in a dark tube, on a de-armed ejection seat, with the nose of the airplane slanted 12 degrees nose-up. The vibration of the then four monstrous (now eight) propeller blades was loud and exhausting.

The air conditioning never worked well, either. Thus, the guy furthest aft always froze his ass off while the NFO closest to the radar boxes burned up.

There were five radios with constant chatter, 20 or more airplanes to control, and radar systems that required constant attention, and so on.

It was busy.

I was always thankful that the airplane didn’t have in-flight refueling capability (that’s changing now). The torture was limited to five hours. A single flight was tiring. Two in the same day was exhausting!

The Downsides Of No Aerial Refueling Capability

Not having aerial refueling capability had its downsides, too.

Late in a six-month cruise, the ship was in the Bay of Bengal, a few hundred miles away from land. We were about four hours into a very rough night training mission and it was time to come “home.”

Our pilots put the airplane into the holding pattern at 15,000 or 20,000 feet, 15 miles from the ship with about an hour’s worth of fuel left onboard. As always, we’d be last aircraft to recover

Burning holes in the sky, the Air Boss announces on the radios, “all aircraft max conserve, deck is foul.”

Huh?

“How long, Boss?” from an anonymous voice.

“About 45 minutes…”

Ugggh!

At the end of a very busy cruise, the non-skid coating on the aft portion of the flight deck had worn down. An F-14 being steered onto one of the waist catapults and slid off the deck and settled on a 45-degree angle in the catwalk below the deck’s edge. The crash and salvage crews were working hard to extract it.

We, in the meantime, started looking at Bingo fuel (minimum safe fuel quantity to return to a landing place) and distance to Thailand. We were in a box. Not enough fuel to hang out, not enough fuel to find land.

But land still seemed like the best option.

I gave the pilots vectors to Phuket, Thailand. They started on a Bingo profile while my crew started working the radios to get clearance into Thai airspace.

Twenty minutes later, the flight deck opened for recoveries again, but we were still Bingo fuel. Now, the ship became the best option.

It was the first and only time that I can remember the mighty Hawkeye being the first aircraft to recover.

Safety First?

The Hawkeye is a typical Grumman airplane with a good safety record. But good does not mean perfect.

Without ejection seats bailing out is a difficult evolution, even in a controlled flight scenario. In an uncontrolled flight situation, it is impossible.

Personally, I got nervous during night time cat shots. If the catapult went “cold,” there was very little chance, if any, that all five crewmen would be able to safely get out before beings run over by an 80,000-ton ship traveling at 20 knots. The sole escape route consisted of an aft hatch, on top of the fuselage, that we kept open during launch and recovery.

Also, the flight controls are operated via a redundant 3,000 psi hydraulic system. The two reservoirs are in the same area as the radar boxes and fed by multiple lines. Any leak would spray high-pressure hydraulic fluid onto a hot radar box and a raging fire could ensue.

If this happened, the airplane was doomed. The crew could blow the main door hatch and bailout, but they’d get cooked in the process. Or the airplane would just lose all use of flight controls and crash.

In 1992, this very scenario happened to a Hawkeye operating from the USS John F. Kennedy (CV 67), killing all five on board including one of my flight school friends, LT(JG) Tom Plautz and a previous instructor, LCDR Al McLachlen.

Ironically, I was informed of that mishap the night I was manning up an airplane and flying to the USS Ranger to start a 6-month cruise.

In the cockpit, pilots had the demands of an unstable airframe, the torque of two large propellers, and no Heads Up Display. Landing on the ship could be a challenge, to say the least.

Several crews have had to bail out of the airplane over the years. There are few occasions where all make it out alive.

When Disaster Strikes

On one occasion, my airplane launched at roughly 21:00 for a routine four hour, “double cycle” flight. The carrier was “Blue Water Ops,” 1,000 miles from nowhere, deep in the Pacific Ocean with nowhere else to land.

As we launched, there were 15 airplanes stacked above us, the previous “cycle,” waiting to come aboard.

About a minute off the catapult there was a piercing voice on the launch/recovery frequency: “BOSS, 602. We gotta land NOW!”

That was it.

The Air Boss’s calm response was “Roger we’re clearing the deck.” And, they were.

Amongst my crew, the questions were already starting, “Fire?” I asked…

Nobody had a real answer.

We immediately went to work. We fired up the radar and began searching for our mates.

Nothing to be seen.

I then called to an F-14 “Wolf, shine west. West. Angels 10 or higher. You see the Hawkeye?” Shine was a term for the Tomcat to point his radar in an indicated direction, looking for a contact.

“Negative.”

We were immensely concerned! “What the fuck?”

A few minutes later the boss announced a clear deck followed by the calming voice of the CAG Landing Signal Officer, Commander John “Bug” Roach.

Somehow and miraculously, the airplane, flown by Erik “Wart” Holtkamp, found the ship from more than 10 miles away on a really dark night.

A few moments after that we heard the LSOs call the trap. But here’s the kicker:

The airplane did, indeed, have an electrical fire in the panel behind Wart’s seat. It burned through everything.

The call to the flight deck was made on a PRC-90 handheld radio by one of the NFOs.

Because Wart had no electrics, he had no radios, cockpit lights or navigation aids. The whole approach was made with a stand-by wet compass and a flashlight, which his co-pilot, John Irvin, held.

Without electrics, the airplane’s rudder stops became inoperative, leaving only two degrees of rudder to control the aircraft. With only two degrees of rudder, Wart had no ability to bolter, or go around. There was not enough yaw control to counter the torque of the 4,950 horsepower engines and two large spinning propellers. A large power addition would simply torque-roll the airplane into the ocean.

To make a long story short, Wart had one shot at the deck. He grabbed the four-wire!

For the next month, the whole squadron was wary. We drove the mechanics crazy, writing up every little squawk. Nitpicking every loose screw!

Not long after that night, I had a radar box burn out, which put a bunch of smoke into the cabin—a fairly benign scenario. Scared the crap out of me, nonetheless!

Wart earned an Air Medal for his outstanding airmanship.

Desert Storm

The afternoon of January 17, 1991, I was standing on the flight deck looking into Iran as the USS Ranger transited the Strait of Hormuz thinking “holy shit… this is it.” Soon it would hit the fan, and a few hours later, it did.

That night the USS Ranger and Air Wing 2 were a major part of the first air raids over Iraq, focusing on the southern cities and ports.

The A-6 Intruders we had on our flight deck provided the Navy’s only true all day, all night, all-weather attack capability. The Tomcats flew Combat Air Patrol (CAP). We Hawkeye guys quarterbacked it all, keeping a close look-out for Iraqi air opposition, monitored the air wing’s assets, and preventing “blue-on-blue” (friendly fire) engagements. With so many airplanes in the sky, and highly caffeinated aircrews on high alert, blue-on-blue incidents were a very real possibility.

The first nights over Iraq were pure, unadulterated, controlled chaos!

During each mission, the NFOs had their hands full. Each controlled a bunch of airplanes, updated surface combatants, kept the radar profile and data links optimized. It was exhausting.

We’d do it for two hours, get a 10-minute break as a new round of attack aircraft entered the fray, and then do it all again for another two hours. Once relieved by the next Hawkeye, we’d head back to the ship, mentally spent.

Once relieved on station, we’d start the journey back to the ship. During the half hour transit, someone would fall asleep. Once, that someone was me and I forgot to lock my harness. Upon snagging the arresting gear, the airplane rapidly slowed to a stop… But I didn’t.

My momentum threw me into the bulkhead circuit board 18 inches in front of the RO seat. That woke me up and hurt too.

Because the A-6’s were optimized for nighttime attacks, that is when we flew. Thus, our day started at 4pm and ended late morning the next day. Breakfast was dinner, dinner was breakfast.

Sometime during the hostilities, the ship’s Captain took mercy upon us and turned one wardroom around 12 hours so that breakfast was served at 17:00.

When You Not Sleeping Or Flying You Are Training

Our Commanding and Executive Officer during Desert Storm, Commanders Pat Madison and Paul Hauser, were big on training.

During transit to the Persian Gulf, they had every officer in the ready-room every day for hours at a time. Topics included aircraft systems, emergency procedures, geography, divert airfields, and everything else we could discuss.

At the time it seemed ad nauseam, but it got us sharp.

Of particular importance were ROE (Rules of Engagement). As the “eyes in the sky” and battlefield commanders, we were expected to know the complicated ROE cold! Again, we spent hours discussing it and working through hundreds of scenarios.

We knew our shit and became the air wing experts. It was our job to be just that.

At one point I was sent to Saudi Arabia to fly with an E-3 Sentry AWACS crew with the goal of understanding how the E-3 operated. The night I got there, there was a USAF General discussing ROE and the crews didn’t know it nearly as well as us. It wasn’t necessarily their fault. The USAF had been on station for several months and were highly tasked. Highly tasked meant little time to do anything but fly. Seeing that I did know the ROE, the General made me do an hour training session and then asked me why I knew it so well. My response was simple:

“If we’re not flying, we’re training.”

There isn’t anywhere to hide on an aircraft carrier. If the CO says, “we’re training,” then you were training!

The follow-on CO and XO were the same. “You will train until you drop!”

And we did, every night.

Bogey And Bandit

Once it was determined during Desert Storm that the Iraqi air force was defeated, the words “bogey” and “bandit” were eliminated from our vocabulary. That is unless it was confirmed that the target of interest was, indeed, a bad guy we were told to never say those words.

At the tail end of the hostilities, we had a section of VF-2 Tomcats flying TARPS reconnaissance in eastern Iraq. The profile was for them to hit the tanker around Baghdad and then fly low towards Basra, take their pictures, and head back to the USS Ranger in the northern Persian Gulf.

Flying above them was a section of VF-1 Tomcats.

I was flying in the ACO seat during the mission, casually watching and listening to the E-3 AWACs control a section of capping F-15s. I start hearing its controller spouting out:

“Bogey, Bullseye south, 50 miles”

Me: “Bulldog, King. Negative. Positive Mode 2 (Military IFF). Coalition aircraft.”

AWACS: “Roger, friendly” followed by an affirmative by the Eagles.

Two minutes later:

AWACS: “Bogey, northwest bullseye, 60 miles heading south.”

Me: “Negative Bulldog. I’ve got positive ID. Navy Hornets.”

AWACS: “Roger, friendly.”

Every time the controller called bogey, the Eagles got spooled up. It probably happened five or six times. I looked over at my CICO, Bob Roth, and chuckled “WTF is up with these guys? Bogies all over the place.”

I couldn’t get the comment out when I heard “bandits, east bullseye 40 miles. Flight of two flying low heading south!”

Shit! The Eagles turned on a dime and started calling their sorts, determining which F-15 would shoot which target. Dash 1 had the lead F-14 and his wingman had targeted the second Tomcat.

In combat terms, “bandit” meant confirmed bad guy. Shoot first, ask questions later. And the frequency got jammed between the E-3 calling out the “bandits” and the Eagles sorting their targets.

All I could do was scream out on the guard frequency (frequency 243.0) “Eagles engaged, King… knock it off, knock it off, knock it off. Friendlies. Knock it off.”

Thankfully, the F-15s heard the calls and immediately disengaged. A few minutes later the voice from the E-3 changed as a new controller took over.

I think someone got their ass chewed.

What was funny is that the TARPS F-14s never knew what was happening. They were on a different frequency talking to the RO in my aircraft. It wasn’t until we were back on the ship when I asked one of them “hey, did you guys get some tones?”

“Yeah, briefly. Came and went, quick.”

We told them the story, and everyone laughed. “Holy Shit! Really?”

Nobody thought anything of it, but someone overheard us talking. From there it made the Admiral’s briefing and got elevated further to General Schwarzkopf who put out a “let’s not go crazy” message to the entire theater.

I got a “good Job” from above, which made me feel good.

On the flip side, a week or so previous the quick thinking of AWACS crew prevented a Navy blue-on-blue when an F-14 mistakenly identified an A-6 as hostile.

Despite inter-service rivalries, everyone had each other’s back.

Towards the end of February, 1991, it was a Sun King Hawkeye, led by Lt. Jack Kennedy, that quarterbacked the final raids on Iraq, known as the “Highway of Death” when USS Ranger’s A-6 Intruders discovered and attacked a massive retreating Iraqi convoy.

Another one of my squadron mates leveraged surveillance assets to target a Silkworm missile launch site. Once located, he controlled several Ranger A-6s and guided them to the area where they dropped a trash load of Rockeye cluster bombs.

To this day, I think the guy who invented Rockeye must have been one sick dude. It is devastating to every living organism in its path.

Just After The Storm Had Passed

Five months into the cruise, the USS Ranger was now heading east towards home, but we got tasked with one more exercise along the way. A B-52 would fly from Guam and try to attack the ship. The goal was to “shoot it down” outside of its missile launch range, which was roughly inside 200 miles. Probably 20 or more airplanes were involved.

We set up our stations with another Hawkeye a few hundred miles away, a bunch of CAP F-14s for fighter protection, EA-6Bs for electronic warfare and S-3s and A-6s to provide gas.

Nobody really cared. It was end of cruise and we were exhausted.

Let’s get it done.

For hours we sat there. Nothing…

At one point, I saw a blip on the radar, far away from any F-14, and well inside the defensive perimeter. I vectored an S-3 Viking to look.

Shazaam! About 20 miles from the ship the S-3 reports a visual on a B-52 flying very low. At about the same time the bomber calls the ship “Ranger, B-52 from the south. Requesting a fly-by.”

Uh Oh!

Five minutes later, with pictures to prove it, the B-52 flies by the Ranger at an altitude below the flight deck, probably 50 feet off the water. Literally, it had been flying at 100 feet or less for several hundred miles, its Electronic Warfare Officer did a great job at detecting and evading our radars.

Oh, boy! We got yelled at and our CO got called into the CAGs office and got yelled at, too.

Later that night we were having cocktails in my stateroom when one of the F-14 RIOs stopped by for a drink. “Yeah, we saw the thing on our radar. We were just screwing around. Didn’t feel like chasing it.”

As I said, the air wing was tired. Nobody cared. We took the heat, but it eventually blew over.

I’m sure we didn’t do our CO any favors, though.

Somalia

Late into my second six-month USS Ranger deployment, we left the Persian Gulf for Somalia and Operation Restore Hope. Nobody knew what we were supposed to do, but we went anyway.

Our missions started simply as a radio relay for the Marines on the ground. Boring stuff. But, a day or two into it we saw that there were literally hundreds of NGO (non-government organization) and military relief airplanes trying to land in Mogadishu all at the same time.

Now that the Americans secured the airport, it was safe to bring in supplies.

It was crazy! Hundreds of airplanes ranging from USAF C-5s to a guy in a Piper Chieftain all converging on a single runway next to the coast.

I was the CICO on the mission and started speaking to my crew. We were going to input an oft-used tactic and modify it for civilian use.

Looking at my RO I said “you start directing airplanes to here,” putting a waypoint on our radar screens. “Stack them 1,000 feet starting a 5,000. Set them up for an approach. Give them push times a few minutes apart.”

Looking at my ACO I said “you keep control of this thing. When one of these guys lands, tell the next to start his approach, then drop the stack down 1,000 feet. Everyone starts their approach at 5,000 feet.”

They got it! We just took charge and began barking orders to the flock of airplanes. Soon we started to sound like New York air traffic control!

The civilian pilots loved it too, as did the military support on the ground. The chaos was getting controlled and we kept it up for nearly five hours straight.

When we got relieved by the next crew, we told them what we did. They carried on the same plan, modified it a little bit more and made it even better.

Upon landing, we debriefed the ship’s Combat Information Center.

Damn if we didn’t start something great!

A day later the Admiral moved an Aegis cruiser closer to the coastal airport and manned it with Ranger air traffic controllers. The Aegis radar is accurate to a gnat’s ass and this now became Approach Control.

The Air Force put some of its folks in the tower with hand-held radios.

The Hawkeye now became Center. We handed off airplanes to the cruiser, who was now Approach Control. They, in turn, handed it off to Tower.

Rudimentary and makeshift, but we now had a fully functioning air traffic control system that stayed in place for several months with the next carrier group, long after we left Somalia for a port visit in Australia.

I was heartbroken when I learned of the Black Hawk Down fiasco several months later.

Panama

During the Summer of 1991, a few months after returning from Iraq, my squadron was sent to Panama to do three months of counter-narcotics missions. The airplanes were parked at Howard Air Force Base. The crews were relegated to Rodman Naval Base, located on the banks of the Panama Canal.

Our accommodations?

For those senior enough there were accommodations in base housing. If not, and I wasn’t, we were sent to a neighborhood of steel Quonset huts furnished with surplus hospital beds and salvaged furniture. The walls in my hut were decorated with Playboys courtesy of the squadrons before us.

Our cooking facilities? An old Weber grill. We had to buy our own food, paper plates, and picnic supplies.

It sucked.

What sucked even worse was the flying. We’d fly at night and head either west to a waypoint in the Pacific or Northeast into the Atlantic. The entire time we’d data-link our radar picture to a Navy frigate. On the occasions we’d see a drug runner, and we did, we’d vector USAF F-16s or other assets to intercept.

The mission was mindlessly boring and it could be dangerous.

Flying 500 miles over open ocean at night is dangerous enough, but we were used to it. What we weren’t used to were huge thunderstorm buildups.

One night, a crew was flying back from a Pacific mission only to run into a line of thunderstorms.

With no onboard weather radar, they had to pick their way through the lines via ambient moonlight. It took them at least an hour to do so and by then they were dangerously low on fuel. In between landing and taxi, the low fuel lights came on. They may have had another 20 minutes of flying time, at most.

Just like the cockpit fire did, we got concerned and started abbreviating the missions a bit.

All Good Things…

After three years, two cruises and two full workup cycles, I transitioned out of VAW-116 with well over 1,000 hours of flight time and 325 carrier landings, the vast majority of which occurred at night.

I also flew more than 100 missions total over Iraq and accomplished what I had set out to do.

At the end of our second cruise, I was a senior Lieutenant, so my CO allowed me to fly home to San Diego commercially from our last port call in Hawaii. The ship needed the space for the onslaught of “Tiger Cruisers,” family of the crew who wanted to experience what their kids experience in the Navy. I think he was ready to get rid of me, too.

When I got on the Northwest Airlines DC-10 in Oahu, I knew I’d experienced my last Cat and Trap.

I was done.

A month later I transitioned to NATO in Germany where I would spend the last two years of my Navy career. From there, I would choose to enter civilian life.

No, it wasn’t my first choice, but the Hawkeye was a rewarding airplane to crew.

I’m forever grateful to the Navy for giving me the opportunity to do so.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com