In the dead of night, a stealthy U.S. military transport plane discreetly weaves its way past dense enemy air defenses to get to a small landing zone deep inside a country in the throes of a coup by a faction violently opposed to the United States. As they get closer to their objective, the crew switches the plane into a vertical takeoff and landing mode, setting it down in a confined area without the need for any sort of traditional runway.

Special operators, which the plane had inserted the same way 24 hours earlier, quickly race onboard. They’ve just rescued diplomats and a handful of other American citizens, some of who are in need of desperate medical attention, who had found themselves trapped inside the country’s capital. After a very short takeoff roll, the transport aircraft leaps into the air before entering into horizontal flight mode. It then disappears back into the night sky as it makes another 1,000-mile trip through the same air defense gauntlet it had overcome just minutes earlier.

This may sound like the climactic finale from a Hollywood blockbuster involving a plane that could have been ripped straight out of a Marvel comic book, but the U.S. military has spent very real time and resources on developing stealthy transport aircraft with short- and vertical takeoff and landing capabilities over the past four decades. In exploring this topic in depth, we here at The War Zone have identified more than a dozen named programs since 1980, as well as numerous additional design studies that private firms have carried out in the intervening years – and these are just the ones that we were able to uncover.

When paired with major historical events and technological developments over the last four decades, a fascinating story materializes that leaves open a very real possibility, if not an outright probability, that one or more of these programs produced flying aircraft and that those machines remain highly classified to this very day.

What follows is the first installment in a two-part investigation into how the requirements for a stealth transport came to be, what configurations were developed to satisfy them, and where are these seemingly missing aircraft that the Pentagon has sought for so many years.

A need slowly emerges

“For all its shortcomings, the helicopter has proven invaluable because of its ability to place an assault force precisely on target, independent of airfields or large unobstructed terrain,” a 1981 report regarding a Low Observable Air Vehicle Engineering Study (LOAVES) from defense contractor LTV, which Reddit user u/aclockworkgreen1 posted online in 2014, explained. “[The] Vietnam experience with helicopters (notably the UH-1) demonstrated that slow speed and a distinctive acoustic signature made a truly surprise [helicopter-borne] attack impossible.”

The desire to be able to discreetly, or even clandestinely, get a significant force deep into an enemy’s territory, past even the densest air defense defenses, and be able to place those individuals and their equipment as close to the objective as possible is hardly new. The limitations of major airborne operations, especially the danger of scattering troops across a broad area and leaving them vulnerable to immediate counterattacks, has been obvious since World War II.

Helicopters offered a partial solution, but one that required staging areas much closer to the objective, which would potentially be at risk from enemy strikes. During the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, the U.S. military as a whole explored a variety of tactical transport concepts, including tilt-rotors and tilt-wings, which would combine the speed and range of a traditional tactical airlifter with at least some of the benefits of a helicopter.

One of the more notable projects was the Tri-Service Assault Transport Program, which ran from 1961 through 1966 and led to the development of the LTV XC-142A tilt-wing aircraft. The aircraft was supposed to be able to carry 32 combat-ready troops or 8,000 pounds of cargo to designations more than 400 miles away. The design proved to be overly complicated and the U.S. military eventually turned over the last of five prototypes to NASA for research purposes.

With more novel concepts, such as the XC-142A, failing to produce practical results, the Air Force settled on more conventional designs, most notably the C-130 Hercules, which did have improved short takeoff and landing performance compared to other transport aircraft of the time. With this in mind, in 1968, the service put together a set of requirements that would lead to the Advanced Medium Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) Transport program, or AMST.

This program produced competing designs from Boeing and the McDonnell Douglas. Boeing’s YC-14A featured two large jet engines positioned forward, above and behind the cockpit to improve lift, while the McDonnell Douglas’ YC-15A featured double-slotted, externally blown flaps that would work to produce similar performance, albeit with four engines in a more conventional underwing arrangement.

In 1979, AMST morphed into the C-X program, which in turn led to the adoption of the C-17 Globemaster III airlifter, an enlarged derivative of the XC-15A. None of these designs were stealthy, though, and they still required an airstrip for terminal operations.

The U.S. Intelligence Community also pursued somewhat similar programs with an eye toward rapidly and discreetly inserting and extracting personnel from hostile countries. One of the best-known examples of this was the Central Intelligence Agency’s modification of two small Hughes 500P helicopters.

These two diminutive choppers had special features that reduced their acoustic signature and various sensors and other equipment to allow them to operate at night over extended distances. In December 1972, pilots from the CIA’s front company Air America successfully piloted these helicopters, nicknamed “The Quiet Ones,” into North Vietnam from neighboring Laos to wiretap North Vietnamese government phone lines.

A crisis in Iran

While the U.S. military might have had an interest in transport planes and helicopters capable of covert and clandestine operations far behind enemy lines for decades beforehand, the Iran Hostage Crisis rammed the need home. After the fall of Iran’s pro-Western monarch Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1979, a group of student revolutionaries took 52 Americans hostage in the U.S. embassy in the country’s capital Tehran.

In April 1980, then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter authorized a hostage rescue attempt, known as Operation Eagle Claw. A highly complex mission from the start, the plan involved flying three EC-130E Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC) and three MC-130E Combat Talon aircraft into Iran together with six RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters.

The EC-130s and MC-130s would carry the rescue force, consisting primarily of Delta Force special operators and members of the Army’s elite 75th Ranger Regiment, as well as supplies to a remote staging area in Iran called Desert One. Crews would then refuel the helicopters and the raiding force would move to a secondary site closer to the Tehran, called Desert Two.

From there, the Delta Force personnel would use trucks and other vehicles to race into the city and rescue the hostages while the Rangers would seize control of the nearby Iranian Air Force base at Manzariyeh. The RH-53Ds would then fly the hostages from a soccer field next to the embassy compound to that base, where C-141 Starlifter transport planes would fly them safely out of the country.

The mission ended early in a literal ball of fire when an RH-53D hit one of the EC-130Es, which was full of fuel, at Desert One. Eight U.S. military personnel died and four more suffered injuries. The U.S. military aborted the mission and abandoned the other five helicopters in the desert, turning the entire event into a highly embarrassing debacle.

The Sea Stallions, and helicopters, in general, were widely seen as a particularly weak link in the original plan due to their limited range and speed, which necessitated the multiple staging areas to begin with. When planning for a second mission began, the proposals included ones in which rotary wing larger cargo aircraft would airlift the helicopters much closer to the target area and others that eliminated choppers altogether.

Credible Sport

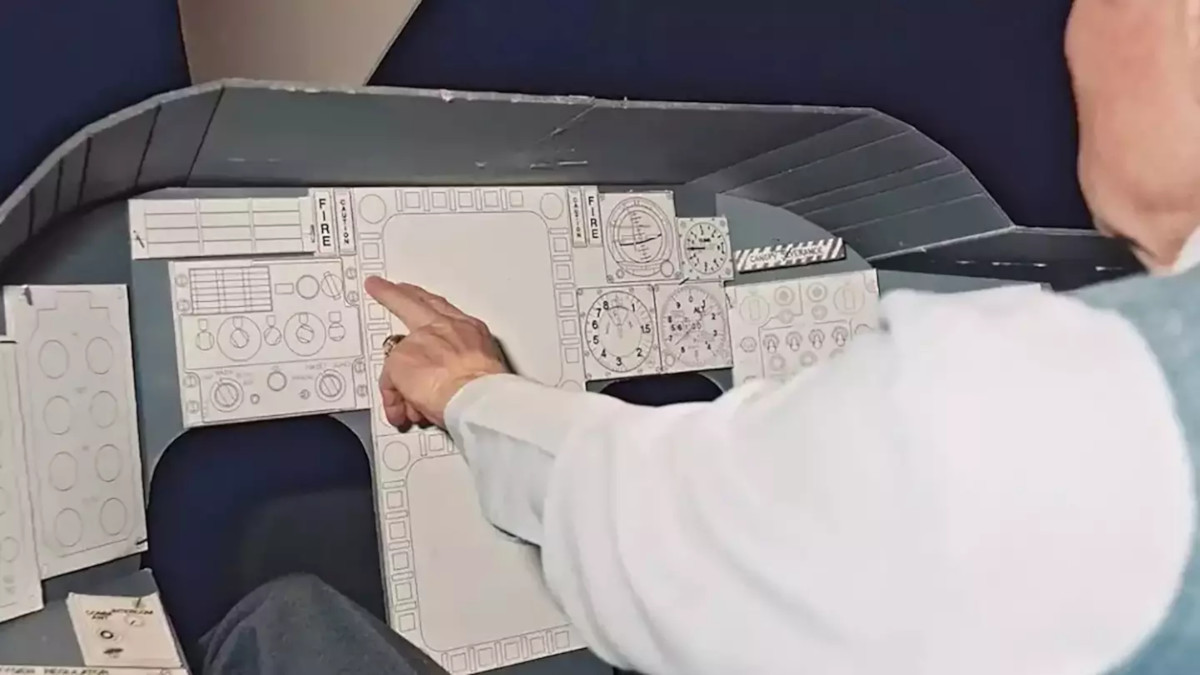

To get the hostages out of Tehran without relying on helicopters, the raiding force would need a novel aircraft that could land and take off inside an extremely confined space. With this in mind, the Air Force acquired a pair highly modified C-130H Hercules cargo planes as part of Project Credible Sport.

That name was an apparent reference to the soccer field across from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, where the RH-53D helicopters were supposed to land in the first rescue attempt. The special C-130s would use that same space as an impromptu “runway.”

This meant that the aircraft had to be able to land and then take off again in the space of just 600 feet. The MC-130Es, then the only available dedicated special operations version of the Hercules, had a typical takeoff run of about 3,500 feet.

Lockheed built the first prototype – variously referred to as the XC-130, XFC-130, and XSC-130 – in just two months. The most visible change was the addition of 30 rocket motors from RUR-5 Anti-Submarine Rockets (ASROC) and AGM-45 Shrike radar-seeking missiles attached to various positions on the fuselage, wings, and tail.

The force from the rockets would serve four distinct purposes: forcing the plane down quickly into a confined space, cushioning that impact, bringing the aircraft to stop, and then blasting it back into the air. The planes also had double-slotted flaps and additional fins above and below the fuselage and wings to help generate extra lift.

In testing, the first Credible Sport prototype was able to get airborne within 150 feet. After traveling the maximum 600 feet distance that the soccer field in Tehran would have allowed for, it was able to hit an altitude of 30 feet and reach a speed of more than 130 miles per hour.

The aircraft never made it to Iran, though. On Oct. 29, 1980, the first prototype crashed and burned spectacularly during a test flight at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. Thankfully no one was hurt.

“Attainment of the rocket-assisted capability is a much needed but secondary consideration,” U.S. Army Major General James Vaught, who had led Operation Eagle Claw and was in charge of the follow-on mission planning, wrote in a subsequent memo that the author previously obtained via the Freedom of Information Act. “Further testing of the rocket concept could be continued once a necessary complement of 16 operational MC-130’s has been acquired.”

Vaught seemed somewhat perturbed that projects like Credible Sport were wasting valuable aerial-refueling capable C-130s, which were in short supply at the time throughout the Air Force. When he wrote his missive, the general had only nine of the 16 Vietnam-era MC-130Es he wanted in total on hand.

In November 1980, the issue became increasingly moot. That month, the new Iranian regime put forward its conditions for releasing the hostages, leading to negotiations, with Algeria acting as an intermediary. In January 1981, the immediate crisis ended when the two countries signed the Algiers Accords. The last American hostages had left Iran by the end of the month.

A turning point

It’s hard to overstate the significance of Operation Eagle Claw and the Iran Hostage Crisis on the U.S. military. The incident at Desert One shook the American special operations community to its core. It directly led to the creation of the elite U.S. Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) as we know it today and impacted every aspect of the of the special operations community, its structure, and its core decision making processes for decades afterward. It drove the establishment of an entire fleet of dedicated special operations fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, among many other types of vehicles and highly specialized gear.

At the same time, it created a new impetus for the clandestine development stealthier airlifters with highly impressive short takeoff and landing capabilities or even the ability to take off and land vertically. In addition, the advancing capabilities of enemy air defenses and the increasing proliferation of those systems, especially surface-to-air missile systems, continued to drive a tangential desire for a stealthy tactical transport design that could penetrate deep into enemy airspace undetected.

“Sophisticated Warsaw Pact air defense sensors and weapons are steadily filtering down to Soviet client states,” the 1981 LOAVES report noted. “Battlefield mobility must be achieved despite the growing threat to aircraft.”

The Credible Sport design was anything but stealthy with its dozens of rocket boosters bolted on externally to an already non-stealthy design. Between 1980 and 1982, the Air Force did pursue a follow-on to this aircraft, known as Credible Sport II, but ultimately abandoned the idea. The service used the prototype, known as the YMC-130H, to support the development of the next special operations-specific C-130, the MC-130H Combat Talon II.

The MC-130H offered updated terrain following radar and other navigation systems improvements, enabling it to better conduct low-level nap-of-the-earth operations, even at night. Enhanced communications were also added to increase connectivity and defense aids were updated to help improve situational awareness and survivability. This presented the lowest hanging fruit for the Air Force to readily obtain at least some form of improved aerial infiltration capability from existing aircraft designs.

The stealth revolution

Despite its improvements over previous special operations transport aircraft, the MC-130H Combat Talon II remained a non-stealthy platform, leaving space open for future low-observable designs. When LTV published its LOAVES study, stealth technology was well on its way to transitioning from a general concept to an operational reality, though these developments remained highly classified. Lockheed’s F-117 Nighthawk was well on its way to becoming the first operational stealth combat aircraft and Northrop’s revolutionary Tacit Blue steath demonstrator was just about to make its first flight.

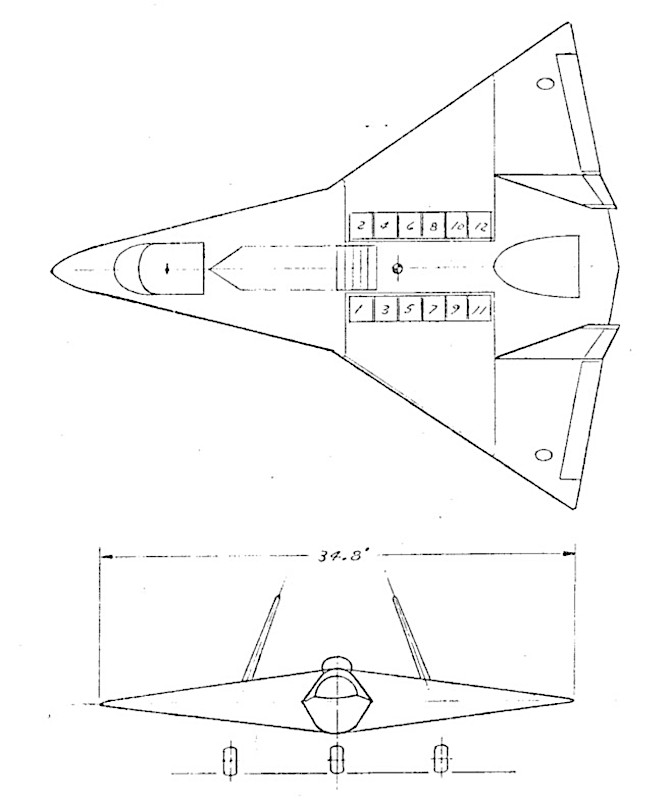

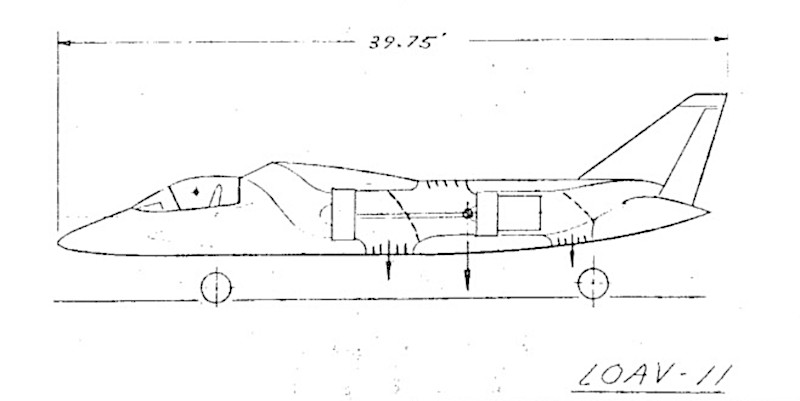

Accompanying illustrations in LTV’s report, shows a notional stealthy aircraft, called the Low Observable Air Vehicle-11 (LOAV-11), with a modified delta wing planform. There are seats for twelve passengers, six on either side of the engine.

During conventional, level flight, the aircraft’s main jet engine would take in air from a dorsal-mounted forward intake, though the engine itself was recessed deep inside the fuselage. The turbofan’s placement, combined with the top-mounted intake, would have dramatically reduced the plane’s radar signature by burying the engine face deep within the fuselage. Northrop used this type of configuration, which is notoriously complicated, in its Tacit Blue design and it has more recently appeared on Boeing’s MQ-25 Stingray unmanned tanker aircraft.

In the LOAVES design, during vertical flight, an internal door would divert thrust from the main engine downward. At the same time, a second door would prevent air from the main intake from passing through to the main engine. Instead, an auxiliary inlet would open up behind the main intake, providing air to the main engine while in vertical flight mode. A driveshaft from the turbojet would then power a lift fan to provide vertical lift at the front of the aircraft.

We don’t know what became of the LOAVES concept, though the underlying requirements clearly informed later projects. The fates of many of those subsequent programs similarly remain a mystery.

AT3 and SOFA

In the mid-1980s, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, one of the Pentagon’s top research and development arms, did hire plane maker Scaled Composites and its enigmatic founder and chief designer Burt Rutan, to craft a proof-of-concept transport aircraft design focused again primarily on extended range and short takeoff and landing capabilities. This project was known as the Advanced Technology Tactical Transport, abbreviated ATTT or AT3.

“Airlift for Special Operations Forces (SOF) has received a great deal of attention since the early 1980s,” defense contractor SRS technologies wrote in a subsequent report on behalf of DARPA regarding the project. “Possibly the most difficult SOF mission is long-range infiltration and exfiltration of small forces deep behind enemy lines.”

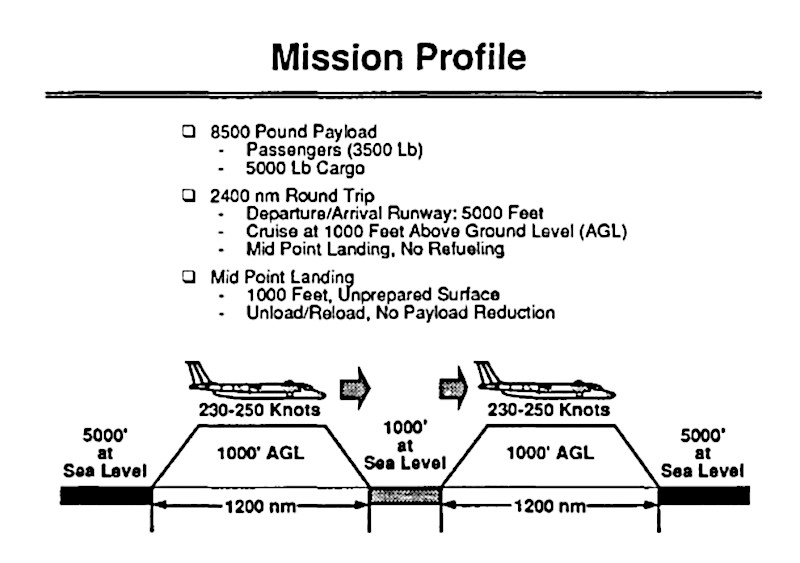

DARPA envisioned an aircraft that would’ve been able to carry 8,500 pounds of passengers or cargo on an unrefueled round-trip spanning more than 2,400 miles. The notional high-low flight profile would involve taking off from an airfield at 5,000 feet above sea level and cruising at 1,000 feet above ground level at speeds between around 260 and 290 miles per hour. The aircraft would then be able to land on an unprepared airstrip 1,000 feet above sea level more than 1,200 nautical miles away before loading or unloading personnel and cargo and then returning to base.

The resulting Scaled Composites Model 133 design, also known as the Special Mission Utility Transport (SMUT), was a twin-engine turboprop with an unusual dual wing-and-flap arrangement to provide additional lift. This was reportedly a two-thirds scale testbed for a possible full-size example. The original configuration featured a traditional tail, but handling problems led to a revision of the design to feature a twin-boom tail similar in basic layout to that of the Rockwell OV-10 Bronco light attack and observation aircraft.

The AT3 effort seems to have either flowed into or run parallel to a related project known simply as the Special Operations Forces Aircraft (SOFA). A 1987 memo from the Advanced Development Projects Office within the Air Force’s Aerospace Sustainment Directorate, then part of Air Force Materiel Command, described this notional platform as having “Stealth Features – High survivability,” a combat radius of around 550 miles, the ability to carry 12 to 20 combat-ready troops, and conduct short take off and landings from unimproved services.

Reddit user u/aclockworkgreen1 also posted this document online in 2014. The memo appears to describe a stealthy aircraft that would have similar capabilities to the V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor, which was also in development at the time. There was also talk of a requirement for 50 such aircraft to enter initial operational service sometime in the mid-to-late 1990s.

Lockheed is rumored to have won the contract to create a concept for the SOFA, which would make sense given its experience with the Credible Sport and Credible Sport II programs, which were then in very recent memory. The company’s Skunk Works advanced design bureau was also at the very forefront of stealth aircraft technology with the work on the F-117 firmly under its belt.

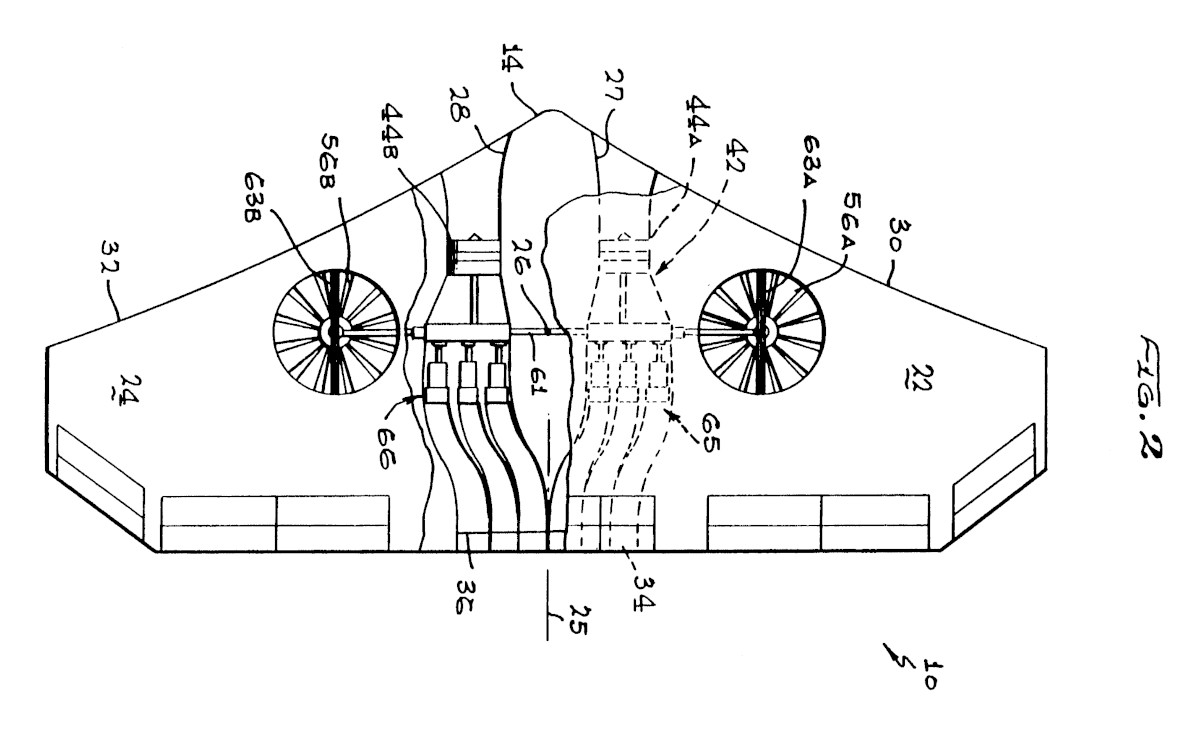

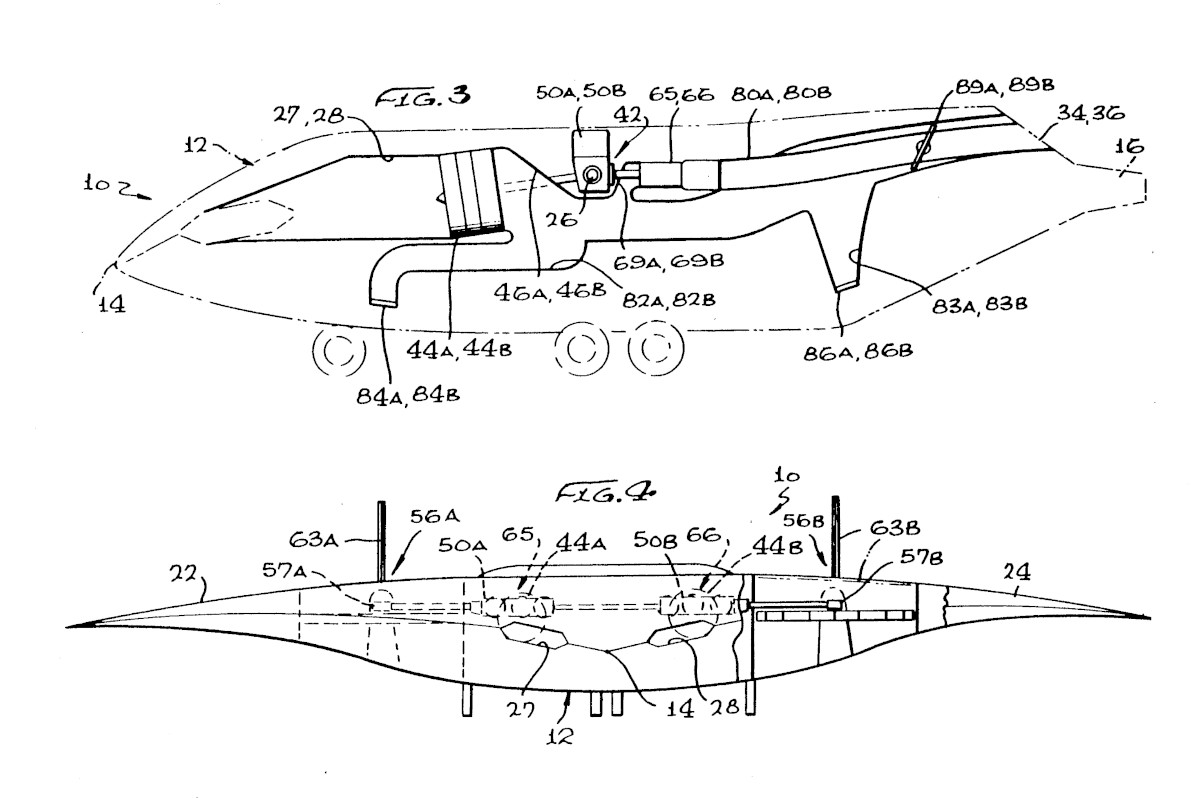

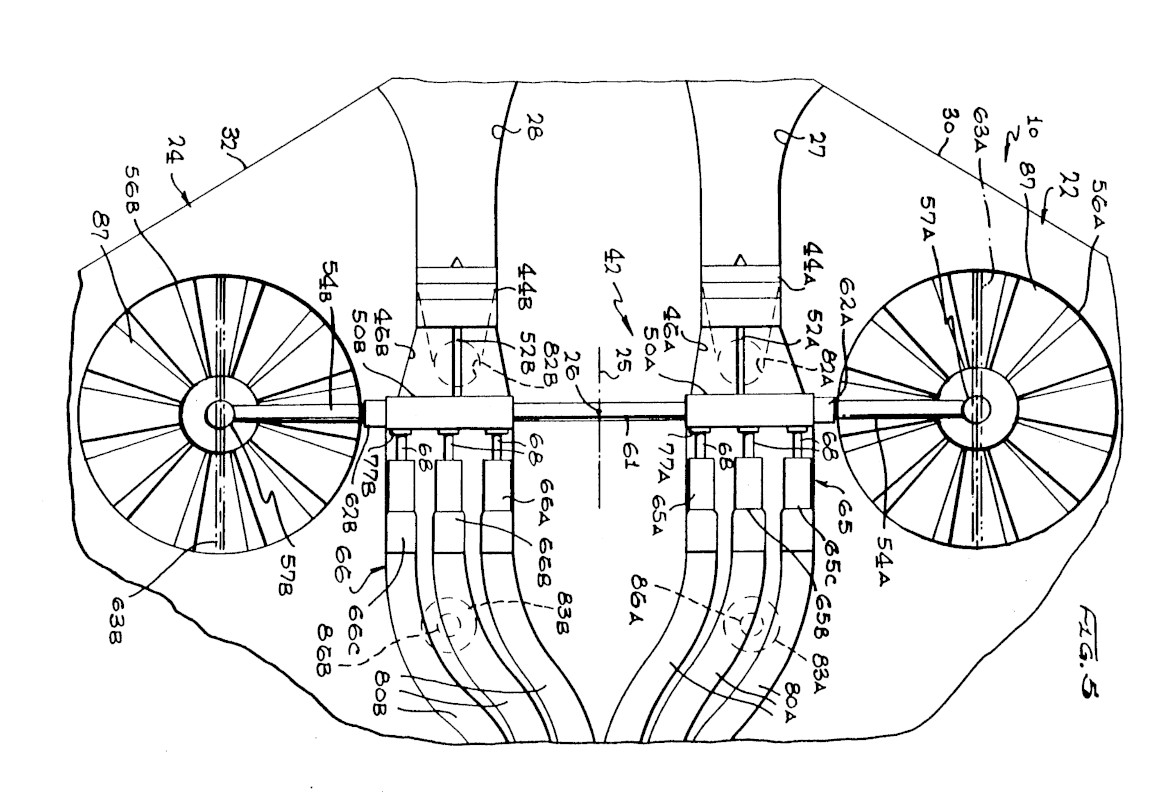

Based on publicly available

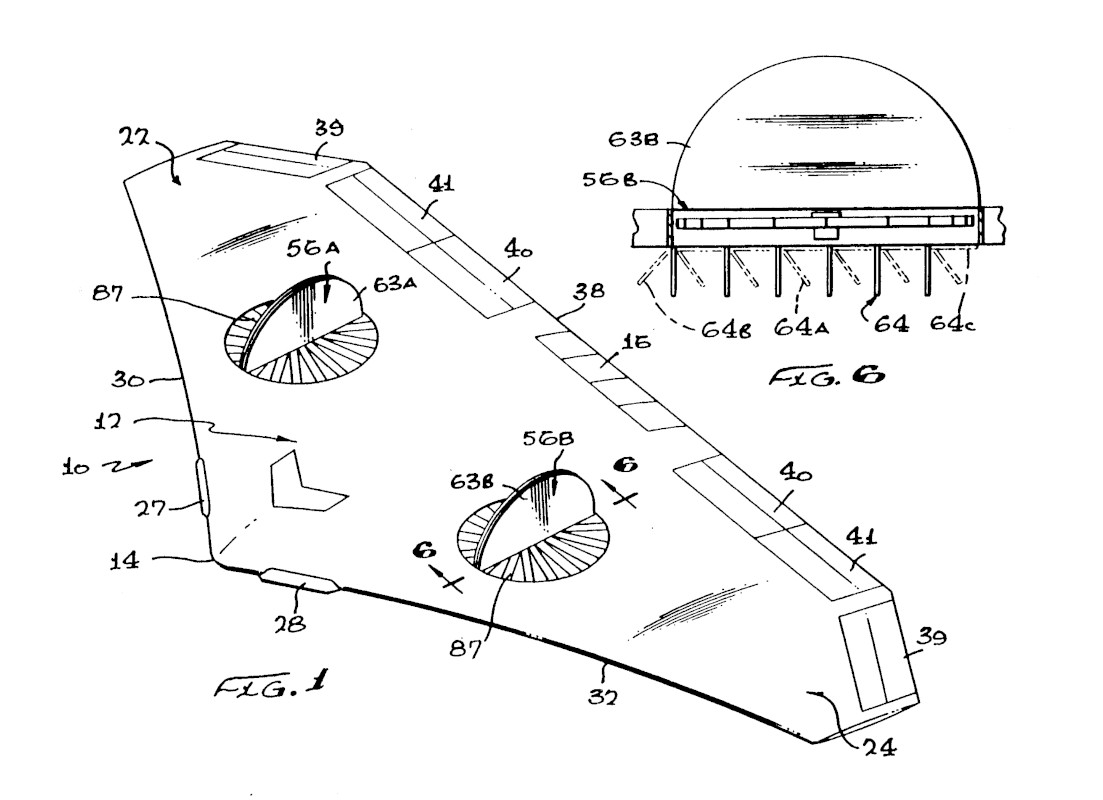

concept art, the proposed design was radically different from a modified C-130. It had a flying wing planform with low-observable characteristics and was, in broad strokes, a lift fan arrangement that was very reminiscent of the one Ryan Aeronautical had used in their Vertifan jump jet prototypes and proposals. Traditional jet engines would provide forward thrust, while two lift fans, one in each wing, would give the aircraft short to vertical takeoff and landing capabilities.

In Ryan’s designs, however, the lift fans were unpowered themselves. When the pilot of a Vertifan shifted to vertical takeoff and landing mode, doors in the wings opened and a valve shifted exhaust from the main turbojet engines to drive the fans and provide lift. It is unclear from the concept art whether Lockheed ever used a similar configuration.

In 1994, the company received a patent for a fan-in-wing propulsion system distinct from the one Ryan had used in the past, involving a set of mechanical linkages between two sets of three turboshaft jet engines and the pair of lift fans, all tucked inside a notional flying wing design. The driveshaft concept is similar at its most basic level to the arrangement that LTV described for their LOAVES aircraft.

The turbofan jet engine in Lockheed Martin’s vertical takeoff and landing capable F-35B Joint Strike Fighter is also connected to the central lift fan via a drive shaft. The SOFA design would have had much larger diameter fans, though.

The planform of the notional aircraft that the patent documentation shows is very similar to descriptions of unconfirmed “black triangle” or “home plate” aircraft that individuals claim to have spotted on numerous occasions in the late 1980s and 1990s. Among the best-known examples is a wave of sightings in Belgium between 1989 and 1990. In on instance, Belgian F-16 fighter jets scrambled to try to intercept an unknown radar contact, but did not find anything. An individual, known only as Patrick M., has since claimed that a purported picture of one of the aircraft was a hoax image he created, prompting additional skepticism about the sightings, in general.

Given the length of time necessary to file a patent and receive an award, it is very possible that this was the engine setup that Lockheed had been expecting to use in its 1980s SOFA project. Lockheed Martin, the result of a 1995 merger with Martin Marietta, publicly revived this fan-in-wing arrangement in 2010, when it unveiled a model of an unmanned aircraft with a similar flying wing design. This subsequently became known as the Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) Advanced Reconnaissance Insertion Organic Unmanned System, or VARIOUS.

Senior Citizen

While AT3 and SOFA were ongoing, another far more secretive project, known as Senior Citizen, was also reportedly in progress. It is possible that the other two programs may have even served as something of a cover for elements of this Special Access Program.

It is also worth noting up front that neither the U.S. Air Force nor DARPA, both of which are understood to have been involved in the project, have ever officially disclosed that Senior Citizen’s work was in relation to a stealthy, vertical or short-takeoff and landing transport aircraft design. At present, no formal confirmation exists in publicly available documents, either.

“This is a special access program,” is one of only two sentences a 2004 Department of Defense manual that defines budget line item codes has in its description of Senior Citizen. “Access will be granted on a strict need-to-know basis only.”

That being said, the Air Force “owns” the so-called “first-word” “Senior” for code names and it has a long history associated with advanced and secretive aircraft projects, including the Advanced Technology Bomber, which evolved into the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber. Northrop’s winning proposal was originally nicknamed Senior Ice, with its competitor from Lockheed known as Senior Peg. After the Air Force picked the B-2 design, it initially referred to it as Senior Cejay or Senior C.J. There’s also the “Senior Trend” F-117A, “Senior Crown” SR-71, “Senior Guardian” Grob D 450/500, “Senior Band” RG-8A, and many more.

There is some public evidence to point to the purported winning design, including concept art of a “Vertical Lift B-2 Concept” from Northrop that appeared in Flight International magazine. “I do not think I can discuss Senior Citizen in any way,” Scaled Composites’ Burt Rutan is reported to have said when asked about the program, further suggesting that it was a real advanced aircraft project.

The exact dates and outcome of the program are still very much unconfirmed. Based on information various individuals have collected, in 1983, DARPA and the Air Force may have hired both Northrop and Boeing to create stealthy, vertical takeoff and landing capable transport aircraft concepts as part of Senior Citizen. This would have come right after the Air Force’s decision to end the Credible Sport II program, the height of the ATB project, and the beginning of the F-117A’s operations.

A flying prototype?

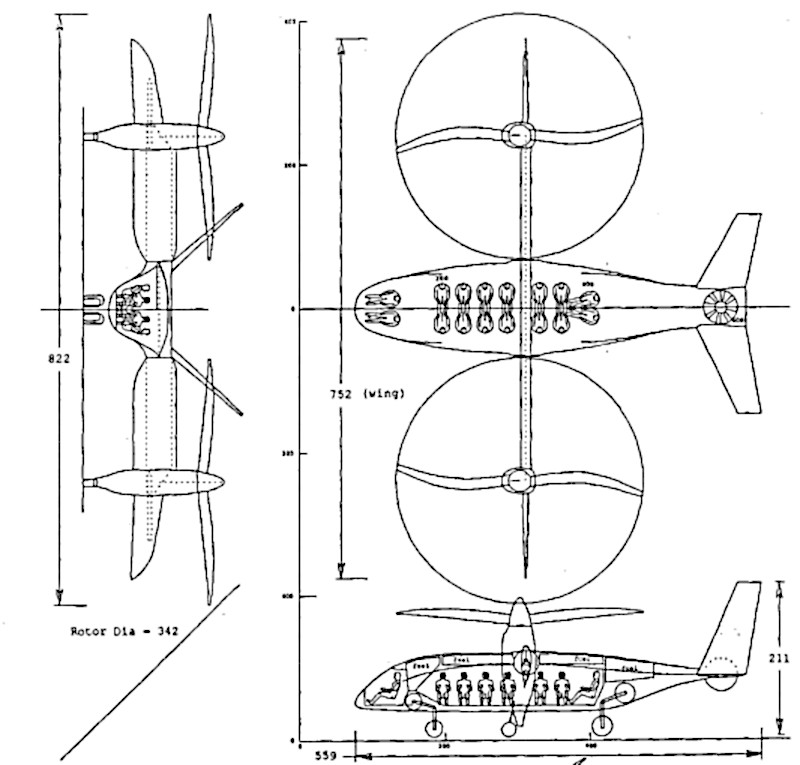

As Senior Citizen progressed, DARPA and the Air Force reportedly picked Northrop’s design, which, if it was related to the artwork that appeared in Flight International, had a rhombus-shaped flying wing-like planform. The engine arrangement was similar to that of the B-2 together with four lift fans, two in each wing.

Other reports describe it as a more triangular shaped flying wing, similar in general terms to the McDonnell Douglas/General Dynamics A-12 Avenger II stealth attack plane design. Senior Citizen may have even pursued two different designs after downselecting from multiple concepts.

It is also entirely possible that Northrop’s public concept art was unrelated to any particular project. The “Vertical Lift B-2 Concept” could also have been a way of actively distracting attention from the program’s actual work.

There have been suggestions that Northrop’s design also featured piping to send either compressed air or bleed air from the engines out through various points on the leading and trailing edges of the aircraft, which could have given it the ability to move side to side and even backward in vertical flight mode. Blown air over the wing could have improved its short takeoff and landing capabilities thanks to the Coandă effect or helped it maneuver in horizontal flight.

Purportedly, at least one type of aircraft to come out of Senior Citizen completed flight testing in 1988 and reached initial operational capability in 1989. Some individuals claim that the Air Force employed one of these aircraft to insert special operations personnel in advance of the U.S.-led liberation of Kuwait and intervention into Iraq during Operation Desert Storm in 1990 and 1991.

There were a number of reported sightings of the Senior Citizen around the United States, as well as at various RAF bases in the United Kingdom, though evidence to support any of these claims is scant. These could easily be reports about seeing B-2s or other known stealth aircraft flying their developmental and operational test and evaluation phases, as well.

Still, the latter reports may help explain a mysterious incident that occurred at RAF Boscombe Down in 1994, which reportedly centered on a mishap involving a top-secret stealth aircraft. However, that incident has links to the Air Force and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which has also suggested the aircraft in question there could have been an intelligence-gathering platform.

“We believe your request as written would more likely fall under the auspices of the U.S. Air Force and Department of Defense,” Allison Fong, Information and Privacy Coordinator at the CIA, wrote in response to a Freedom of Information Act request we had submitted regarding Boscombe Down. It is noteworthy that the Agency did not refuse to confirm or deny that any such incident had occurred at all.

The Air Force Safety Center responded to an identical FOIA request saying that it had no information about a mishap involving one of the service’s aircraft at Boscombe Down in 1994. Air Force Materiel Command has yet to respond to a third request on the matter.

A flying Senior Citizen aircraft would not have automatically meant that the plane was operational or in production, either. Whatever the case, the Senior Citizen Special Access Program ceased to be active sometime between 1993 and 1994. After that, any design work or flyable aircraft would have come under the purview of other programs and budget funding streams.

Other work continued

Whether or not Senior Citizen led to the introduction of an actual stealth transport or not, it definitely did not stop the Air Force from continuing to pursue related developments. In the early 1990s, while the Special Access Program was still active, yet another project began, known as the Special Operations Forces Transport Aircraft (SOFTA).

LTV Aircraft Products Group started its design study in May 1991, outsourcing the work to none other than Burt Rutan and Scaled Composites, though the LOAVES study suggests the company had been looking into the design of such an aircraft for at least a decade beforehand. It’s also worth noting that Rutan had worked on the XC-142A project, another LTV product, in the 1960s. LTV also helped in the production of the B-2 bomber.

LTV’s requirements, which are similar to those for the LOAVES concept, were relatively limited when it came to load-carrying capacity. The company sought designs that would only be able to carry a 12-man Army Special Forces A Team and 500 pounds of cargo, for a total payload weight of 4,500 pounds. By comparison, a V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor, a non-stealthy aircraft with a similar dimensional footprint, can carry twice as many personnel and up to four times that total payload weight internally.

As with the aforementioned Advanced Technology Tactical Transport (ATTT) requirements, the SOFTA aircraft would need to have a combat radius of more than 1,000 miles and be able to self-deploy to forward operating sites more than 2,400 miles away, according to LTV reports. The goal was also to have a “low to moderate” radar and acoustic signatures and have both short and vertical takeoff and landing capabilities.

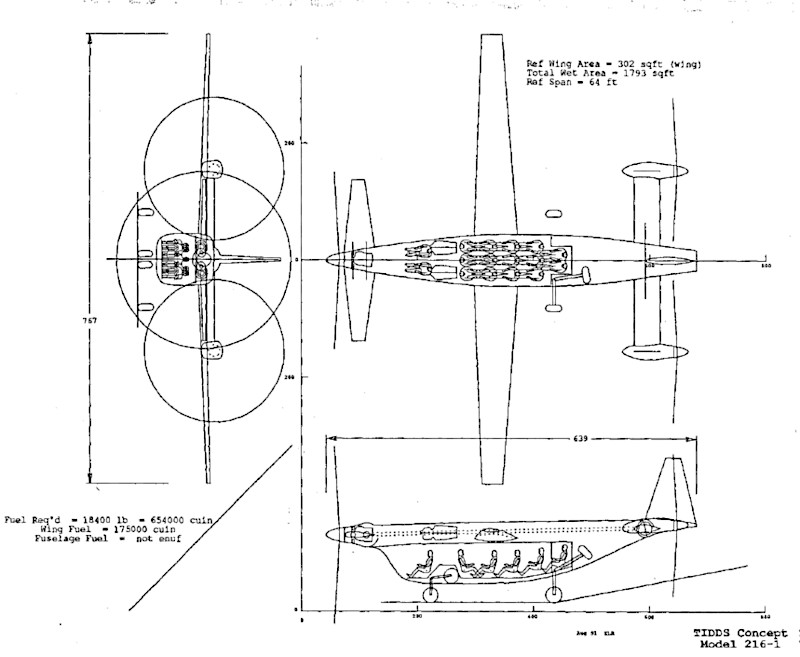

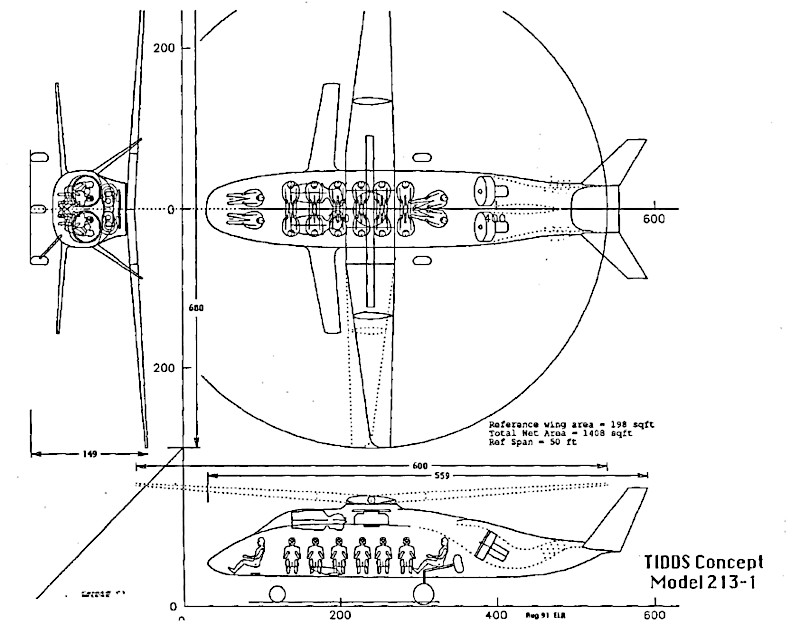

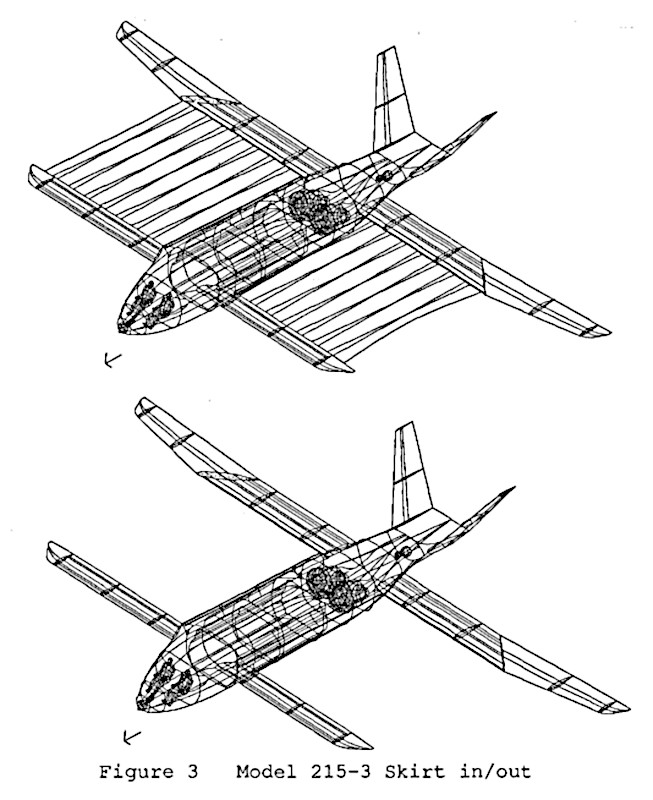

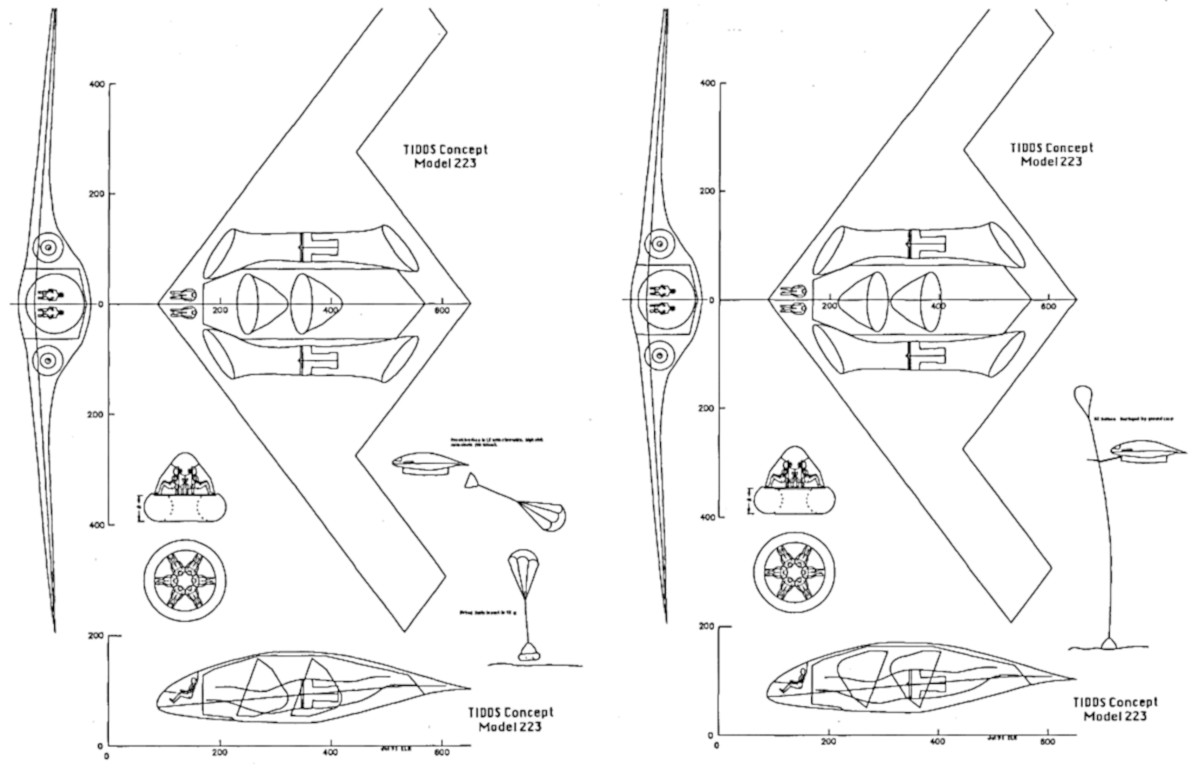

Rutan quickly provided a dozen design concepts, with LTV eventually selecting six of them – the Models 209, 213, 215, 216, 220, and 223 – for further study in October 1991. Each one was significantly different.

The 209 was perhaps the most conventional, being a twin-engine tilt-wing design similar in basic concept to the XC-142A and in some respects to the V-22. The 216 had three tilting engines, one in the nose and two on either side of the rear fuselage, all separate from a central wing.

The 213 was similar in some respects to a compound helicopter, which a multi-bladed main rotor assembly on top of a fuselage with a conventional wing and tail arrangement. In this design, the rotor would stop during forward flight.

The 215 was another one of Rutan’s tandem wing designs, but featured a retractable skirt between the main wing and front canard on either side. When deployed, this would have given the jet-powered plane the appearance of a flying squirrel.

“For SuperSTOL operations, the aircraft is slowed to near the stall speed, then is continuously slowed as the skirt is unfurled laterally between the canard and wing,” Rutan explained an October 1991 report to LTV. “The skirt edges are retained in tracks similar to that used on high-performance racing sailboats using a continuous root-to-tip cable loop at the canard and the wing.”

Aft- and downward-facing rockets would help the plane land in a very short distance, similar to the Credible Sport C-130. Additional rockets would have helped it take off again.

The 220 was a twin-engine turboprop all-wing design, similar in many aspects to the World War II-era Vought V-173 “Flying Pancake” and XF5U “Flying Flapjack.” Unlike those aircraft, Rutan’s plane would have landed vertically on its tail and taken off in the same fashion. Various U.S. military services had experimented with similar designs, such as the Convair XFY, in the 1950s.

Perhaps most interesting of the concepts was the 223, which was a low-observable flying wing similar in basic planform to Northrop’s initial Advanced Technology Bomber designs. Instead of landing to insert and extract personnel and cargo, the plane would release a number of parachute-retarded pods. This portion of the concept also had a certain amount in common with capsulized emergency escape systems present on certain Cold War combat aircraft, notably the F-111 Aardvark.

At the end of a mission, the plane would return and scoop them back up while still in flight by using a system similar to the Fulton Recovery System, or Skyhook, which you can read about in more detail here. It’s not immediately apparent how the plane would fully reel the pods back inside. With Skyhook, the “captured” individual trails behind the aircraft and personnel in the rear use a separate system to haul them onboard. DARPA’s more recent Gremlins reusable drone program is evaluating a similar aerial recovery mechanism.

It’s not clear what happened to any of these designs or the SOFTA project as a whole. LTV expected to have a final design make its first flight in 1994, but there’s no indication this happened, at least not publicly. It is possible that the program was yet another extension of the work done under Senior Citizen or a further cover for those developments.

As with earlier projects, such as Senior Citizen, multiple companies may have taken part in the SOFTA program. LTV may have developed its SOFTA concepts as part of a U.S. military project with a separate name that involved multiple firms, as well.

We do know that in the early 1990s, Northrop was also working on developing its own stealthy assault transport design that it referred to as the Special Operations Low-Intensity Combat Mission Aircraft, which was smaller than the B-2-like aircraft reportedly under development as part of Senior Citizen. We at The War Zone were the first to report on the existence of this special operations transport project, which appears to have been closer in general size and scope to LOAVES and SOFTA concepts.

What’s to come in Part II

With all this historical context laid out in detail, part two of our expose dives into the really exciting material. Our research paints a clear picture of how these requirements not only never went away, they actually expanded as the new millennium arrived.

After the events of 9/11 and the dawn of the Global War On Terror, followed by the emergence of the age of ‘great power competition’ and anti-access/area-denial warfare strategies that we are in today, the need for special operators to be able to rapidly insert deep into highly contested territory has become more pressing than ever. As our investigation draws closer to the present day, we have uncovered detailed information about a number of initiatives that aimed to provide just these type of capabilities.

Maybe most importantly, we also discuss the very real possibility that some of these concepts have not only flown, but that they could very well be in an operational state today. If not, the far bigger question is could such a reality even be possible after 40 years, dozens of initiatives, and untold sums of money having been thrown at the problem.

Buckle up for a voyage into the darkest corners of America’s special operations arsenal.

Continue to part two of this story by clicking here.

Contact the authors: joe@thedrive.com and tyler@thedrive.com