The Government Accountability Office recently announced it had rejected a protest from the Airborne Tactical Advantage Company, or ATAC, over a U.S. Navy multi-million dollar contract award for “red air” aggressors that went to its less established competitor Tactical Air Support, Inc., or TacAir. The supporting documentation offers extremely interesting insights into the requirements the service had asked of prospective private contractors and the capabilities those firms offered. The information is especially enlightening as the U.S. Air Force is likely taking similar factors into account as they consider bids for their own massive adversary support deal.

GAO only posted its decision online in November 2018, despite having reached its conclusion on Sept. 28, 2018. The decision has been “subject to a GAO Protective Order” and now publicly available in a redacted form. Under the contract, worth $118.9 million over the next five years, TacAir will support the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC) and the Navy Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor program, better known as Topgun, both of which are located at Naval Air Station (NAS) Fallon in Nevada. They will also provide aggressor duties for carrier air wing workups which happen a few times throughout the year. A fleet of at least five modified F-5AT jets will fly a combined total of approximately 1,700 hours annually under the fixed-price deal.

A fuller description of the basic mission set this new force of private aggressors would provide is described as such in the GAO’s documentation:

Pursuant to the PBWS, the awardee was to provide contractor owned, operated, and maintained aircraft for a “wide variety of airborne threat simulation capabilities to train aircraft squadron aircrew and shipboard system operators on how to counter potential enemy advanced airborne threats, tactics, Electronic Warfare (EW), and Electronic Attack (EA) operations.” More specifically, the awardee was to provide “tactically-relevant 4th Generation fighter jets for air-to-air tracking, targeting, and tactical intercept, offensive/defensive counter-air, and air interdiction operations to include associated equipment systems that interface with various platforms and ground force personnel.” Contractor aircraft were to simulate non-western threat aircraft capabilities in an air-to-air environment.

So basically, these aircraft would serve in a similar role as Fallon’s resident fleet adversary support unit, VFC-13, but would be enhanced with, at a minimum, better radars, radar warning receivers, and electronic warfare capabilities.

Contract protest

“ATAC primarily contends that the aircraft the awardee proposed for performance cannot meet various technical requirements. ATAC also challenges the evaluation of the awardee’s technical risk and price realism, as well as the agency’s best-value determination,” GAO explained in its formal decision. “We deny the protest.”

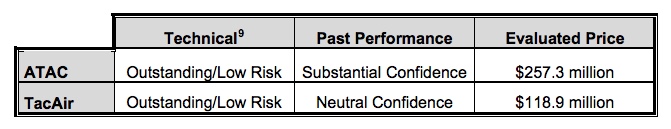

It’s undoubtedly a major blow to ATAC, the incumbent, which has been supporting those training activities for more than 15 years and has provided more than 50,000 hours of adversary support in the process. TacAir’s bid was also less than half the price of ATAC’s proposal, pointing to a potential cost issue that may become a major factor in future adversary contracts, just as it has been in other high-profile U.S. military purchases as of late.

ATAC’s pitch had centered on providing ex-Jordanian F-16AM Viper fighter jets, which would have much higher performance than TacAir’s upgraded ex-Jordanian F-5s. However, they would also have been far more expensive to operate and less reliable.

Altogether, ATAC had argued that TacAir’s proposal did meet the Navy’s basic performance requirements, it failed to adequately account for the service’s stipulations about radars in the aircraft, did not provide enough planes to begin with, and was unrealistic in terms of the quoted final price for the services. In rejecting each one of these claims, the GAO provided very granular details on TacAir’s winning proposal, many of which are interesting in their own right.

Aircraft performance

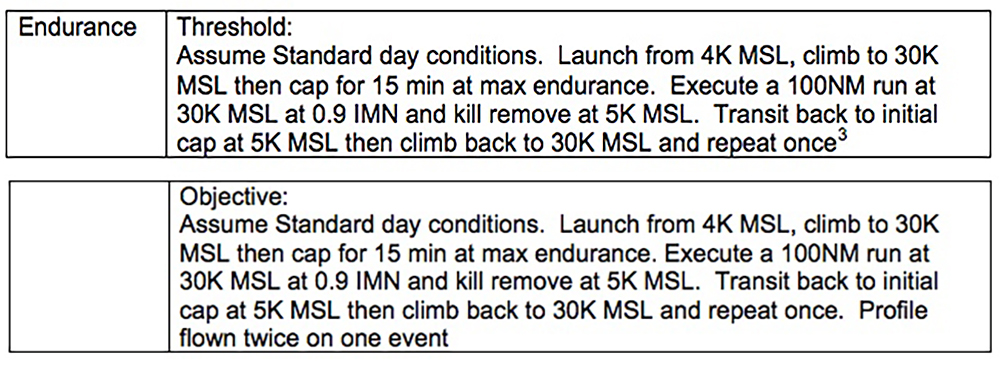

ATAC protested the Navy’s contract award to TacAir in part because it contended that its competitor’s F-5s could not adequately or safely meet various performance requirements. This included arguments that the jets did not meet the Navy’s endurance needs and would not be able to provide “24/7” availability for all missions due to the aircraft’s potential limited ability to fly in certain configurations in hot weather.

The Virginia-headquartered incumbent initially asserted that the F-5s would simply not be able to meet the endurance requirement at all. “Upon review of the record, the protester acknowledged that when TacAir’s F-5s were configured with a [redacted] external fuel tank the F-5 would be able to fly the threshold level endurance profile after all,” GAO noted.

ATAC then claimed that the addition of the single drop tank on the aircraft’s stores station would prohibit the jets from safely taking off when the ambient temperature was over 68 degrees. This, in turn, would render the aircraft unavailable for long endurance missions for much of the year at NAS Fallon, where temperatures routinely exceed that.

The F-16AMs would have no such restrictions, according to ATAC. TacAir and the Navy countered by saying that ATAC had misinterpreted the performance parameters in the F-5 operator’s manual, deliberately or accidentally, and that the jets would be able to operate with the external tank even if the temperature reached 115 degrees.

“We afford particular deference to the technical expertise of agency personnel regarding judgments that involve matters of human life and safety,” GAO said. The watchdog also said it could find no actual mention of a 24/7 availability requirement in the Navy’s contracting documentation.

“Aviation operations may be limited based on all types of weather,” TacAir had told GAO itself. “For instance, an aircraft, such as the one proposed by Protester, may be restricted from flying or limited in its ability to meet certain performance requirements during a thunderstorm.”

ATAC’s final complaint about the performance of F-5s centered on the ability of the aircraft to perform various mission sets, including those requiring certain maneuverability parameters, with the external tank fitted. GAO rejected that argument saying that TacAir had proposed multiple aircraft configurations to meet different mission stipulations and that the Navy had not required the winning party to provide a single type of aircraft in a single configuration to meet all of its needs.

Different radars

The Navy’s contract required potential contractors to offer aircraft with a sufficiently advanced mechanically scanned array (MSA) radar, as well as provide a path toward potentially adding an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar into at least some of their aircraft. If the service pursues those optional line items, TacAir will need to have one AESA-equipped jet in its fleet within 18 months and a second within 30 months.

ATAC argued that the F-16AMs it planned to acquire from Jordan would already come with a suitable MSA radar and that there were already AESAs available on the market specifically for the Viper. Throughout GAO’s discussions, the names of all of the specific types of radars are redacted, but the F-16AM already has an AN/APG-66 MSA type. Raytheon’s Advanced Combat Radar (RACR) or Northrop Grumman’s Scalable Agile Beam Radar (SABR) are AESA radars that can easily slot into the F-16. There are also foreign options, like Israel’s EL/M-2052 and possibly a variant of Selex’s promising ES-05 Raven.

As such, ATAC felt TacAir’s proposal, which involved modifying all of its F-5s with some type of new radar, should have been considered “high risk” rather than “low risk” and counted as a strike against their bid. GAO disagreed, saying it found no clear fault in the other contractor’s plans.

TacAir actually put forward three radar options. Based on the information GAO received, the firm will provide the Navy with four aircraft with one type of MSA radar that meets the threshold requirements and a fifth aircraft with a separate, more advanced type. If the Navy opts for the AESA option after that, the small fleet of TacAir aggressors working at NAS Fallon could theoretically end up with three separate radar types of varying capabilities, or at least two types regardless of if the AESA option is executed or not.

Although it is not spelled out in the GAO’s report, it is likely that a data-link system will allow the F-5AT fleet, which is receiving a massive avionics upgrade beyond just new radars, to take advantage of the best available radar in the formation. As such, a single high-end radar-equipped jet out of a formation of four aircraft is a huge force multiplier and would help significantly with portraying more capable enemy threat profiles.

It is highly unlikely that this means the first four F-5s will retain their very dated and limited AN/APQ-153 or AN/APQ-159 radars originally installed the Tiger II. In addition, TacAir’s website says that its jets have one of or a mix of AN/APG-66s (same radar on earlier block F-16s) and Leonardo Grifo-series pulse-doppler types.

TacAir did cite upgraded Brazilian F-5EM, Singaporean F-5S/T, and Thai F-5T aircraft, as well as the F-20 Tigershark and F-5E Tiger IV, as examples of the ease of installing improved MSA radars into the aircraft. The F-5EM and F-5S both have Grifo-F radars, while the F-5T has an Elta EL/M-2032, another popular compact pulse-doppler type. There is no evidence that TacAir’s F-5AT designation has any relation to the Thai F-5T configuration.

The F-20, an advanced F-5 derivative Northrop unsuccessfully pitched to the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Navy and other customers in the 1980s, featured General Electric’s AN/APG-67. This radar is still found in other light fighters, like Taiwan’s AIDC F-CK-1 Ching-kuo and Korean Aerospace Industries’ FA-50. It is possible that TacAir could end up equipping its initial F-5ATs with this radar set, but more capable and more plentiful systems are now available.

GAO said TacAir also provided a detailed schedule outlining its plans to install an AESA radar into another aircraft if required. Though we don’t know what type of radar the company has in mind, and as we noted earlier there are multiple options, Northrop Grumman’s SABR would be particularly attractive considering the company that makes it is the F-5 OEM and is already doing the rehabilitation on the company’s airframes at their facility St. Augustine, Florida. It is also a cutting-edge system that would provide many years of relevance and big capabilities to the F-5AT fleet.

Although not entirely conclusive, the GAO’s posting also seems to point to Northrop Grumman’s SABR as the AESA option in the following passage:

With respect to TacAir’s solution for AESA capability, the [DELETED] system, the agency points to TacAir’s detailed explanation of how it intended to exceed the RFP’s capability standup requirements and integrate the radar system into its F-5s within 10 months. The agency highlights that TacAir proposed to use the same radar bulkhead modifications that it already planned for its baseline aircraft. Moreover, the Navy specifically notes that the [DELETED] radar would “fit within currently defined power and cooling requirements and support the existing pilot-vehicle interface.” The agency also points out that [DELETED] is the manufacturer of both the [DELETED] and the F-5, and the awardee proposed that [DELETED] would be TacAir’s “partner for aircraft re-assembly, modification, and depot level maintenance.” In fact, according to TacAir, [DELETED] had previously demonstrated system performance with a comparable radar in the F-5E.

The dimensional constraints of a modified F-5 nose more in line with the configuration of the one on the F-20 is also stated as evidence that packing a more powerful radar into the F-5’s general design is both possible and has actually been implemented before by the OEM itself.

TacAir’s radar modification proposal was more complex than ATACs, but the Navy agreed with the company’s assertion that it followed well-established procedures that have already been used to upgrade 127 F-5s around the world. As such, there was no concern that the upgrades wouldn’t be complete within the required schedule.

How many planes?

Another of ATAC’s contentions was that TacAir would not be able to provide the necessary capacity the Navy had demanded with only five aircraft on the flight line at Fallon. ATAC’s proposal was to have nine F-16AMs on site from the beginning. GAO rejected the argument that the service had “improperly relaxed the requirements by allowing TacAir to ‘get away with only four aircraft,’” stating that the language outlining the requirement in the original contracting documentation was clearcut.

However, TacAir had stressed that its five jets would only be an “initial operational capability,” and that it would have 10 aircraft available in total, both at Fallon and in reserve elsewhere, within a year. This would include two AESA-equipped jets if the Navy decided to pursue that option.

The Navy told the GAO it was fully aware of the nature of TacAir’s proposal and, as a result, the watchdog deferred to the service’s belief that this would meet its requirements. Having five aircraft on site, with four operational and one in reserve, does meet the bare minimum requirements for the contract, but does raise questions about whether it allows for any surge in training missions, especially in the first year.

Though TacAir says that it only expects to fly around 1,700 hours annually, the Navy told GAO that the firm was aware that this number could actually be as high as 2,300 hours per annum. TacAir would need all 10 planned aircraft to meet that demand and has no plans for that added capacity to be available in the first 12 months.

TacAir does have the added strength of being located in Reno, Nevada, approximately 60 miles from Fallon, which could allow it to more readily surge aircraft to the Naval Air Station as necessary. It also allows TacAir to more readily swap out aircraft for necessary heavy maintenance and avoid gaps in service. Also, as we noted earlier, a sizable contingent on contractor-maintained F-5s are already located at Fallon. So there may be substantial synergistic impacts of adding more of the same type to the flight line.

Aircraft fatigue life was also a major factor in the contract tender. With older aircraft, the question of could either company provide enough airframe life with the aircraft allotted to complete the contract was clearly relevant. TacAir, which already owns its F-5s unlike ATAC with its proposed F-16AMs, provided extensive details about each aircraft in their existing stable that would be used to support the contract and it was made clear that they would have no trouble achieving the tender’s maximum flight hour requirements.

The issue of only having five aircraft, at least initially, to fly four aircraft missions potentially twice a day (four-turn-four) was also raised with TacAir’s proposal. Under such a scheme the company would have to deliver roughly an 80% mission capable rate. The reality is that F-5s currently flying for the Navy achieve that and more as the type is fairly simple to maintain and operate, especially compared to complex 4th generation fighters. So this argument was also batted down.

“Ultimately, while ATAC is unsettled by the prospect of only one spare aircraft on the flight deck – instead of the two spares it proposed to utilize – the Navy did not share ATAC’s concern,” GAO concluded. “We will not sustain a protest where the agency’s evaluation is reasonable, and the protester’s challenges amount to disagreement with the agency’s considered technical judgments regarding the specific elements of an offeror’s proposal.”

‘Price realism’

With all of these other complaints in mind, ATAC’s final argument was that TacAir’s bid, whether or not it met the Navy’s requirements, had an unrealistic total price. “To support its arguments, ATAC performed its own detailed assessment of TacAir’s proposed prices and concluded that the awardee faced ‘extremely significant’ losses as a result of pricing the contract too low,” GAO noted.

The Navy actually came to this conclusion itself and asked TacAir to reassess the total cost of its bid, which it did. This implies that the firm original offer was even lower than the final price point of $118.9 million. This is substantiated by earlier reports that the contract was worth less than $106 million.

The Navy had also issued the contract as a firm, fixed-price deal, which the service, as well as other branches of the U.S. military, have been increasingly using to help save money and limit risk. As such, there was no specific requirement to analyze TacAir’s cost estimate, since the company would have to accept any cost growth.

“Unrealistically low prices or inconsistencies between the technical and cost proposals may be assessed as proposal risk and could be considered a weakness under the technical factor,” was something the Navy had included in its original contracting documentation. However, as noted, it only accepted TacAir’s proposal after revision.

The firm had also employed a novel pricing strategy to only charge the Navy depreciation costs for the minimum four operational aircraft. It would effectively eat those costs for the six other aircraft it could end up committing to the red air mission at Fallon over time.

It is reasonable to question whether this is a sound business strategy in the long-term and it does carry some inherent risk about whether the company will be able to remain solvent over the course of its contract with the Navy. At the same time, for TacAir, the prospect of any losses was clearly acceptable in order to take over an expanded version of ATAC’s long-held role at Fallon, which could put it in a good position for future contracts if it performs at or above expectations.

This could be a very relevant issue in the coming years as the U.S. military as a whole continues to expand its use of private contractors to provide “red air” adversaries for training and exercises. Doing so helps reduce the strain on U.S. military personnel and assets, freeing them up for higher priority missions, and reducing costly wear and tear on advanced aircraft while also saving money. It actually enhances training in some ways as well and brings a different perspective and unique gear to the fight.

The U.S. Air Force, in particular, wants to begin awarding contracts in 2019 for aggressor support at a dozen locations or more. Those deals could be worth up to $7.5 billion in total between 2019 and 2029.

TacAir and ATAC, along with other competitors, such as Draken International, are competing for those contracts. We could easily see one or more of these firms use novel pricing schemes to try and undercut each other.

We have already seen similar strategies emerge in major aircraft production deals recently. Boeing secured contracts to build the Air Force’s T-X jet trainers and MH-139 utility helicopters, as well as the Navy’s MQ-25 drone tankers, by offering significantly lower bids than its competitors. Those awards all went unchallenged.

A final decision

Footnotes in the GAO’s report also give us a glimpse into the other criteria that were examined and scored, although exactly how large an impact these criteria had on the final decision remains unclear. The report states:

ATAC’s F-16s met the objective level performance requirements in the following areas: speed, ceiling, turn, endurance, mission recording, identify friend or foe, communications, data links, and electronic warfare.

TacAir’s F-5s met the objective level performance requirements in the following areas: ceiling, mission recording, identify friend or foe, communications, data links, infrared captive air training missiles, and electronic warfare. TacAir also was assessed a strength for its radar warning receiver capability.

In the end, it was decided that the advantages the F-16 brought to the table just didn’t outweigh the cost difference for this specific mission set. With the GAO summarizing the decision as such:

In assigning the proposals outstanding technical ratings, NAVAIR evaluators identified numerous aircraft performance categories where the offerors’ proposed aircraft met or exceeded the objective level performance requirements, as well as other areas where the proposals reduced risk. Specifically, for ATAC’s proposed F-16s, the evaluators assigned strengths for meeting nine objective level performance metrics, and the evaluators identified six proposal features that reduced risk. TacAir’s modified F-5s met seven objective level performance metrics and included one feature that would enhance the training mission, and the proposal contained two aspects that reduced risk. Price evaluators also documented the offerors’ notably different approaches to pricing the fixed-price contract. The evaluators observed that the “large variance” in proposed prices was “largely contained within . . . the price of acquiring, operating, and maintaining the proposed aircraft in baseline configuration.”

Specifically, ATAC, which proposed the second highest price of the offerors, included in its proposed price the costs of purchasing all nine of its F-16s and importing the aircraft to the [United States]. TacAir, which already owned its F-5s, included in its lowest-priced solution only the depreciation costs for the RFP-required minimum four aircraft, among other price-saving measures. The evaluators also highlighted that F-5s “typically have lower acquisition and maintenance costs.” The SSEB briefed a source selection advisory council (SSAC) on its evaluation findings… and the SSAC prepared a report recommending that TacAir be awarded the contract.

The source selection authority (SSA) thereafter performed a comparative assessment of proposals. In his tradeoff, the SSA plainly acknowledged that the F-16 aircraft had a“performance advantage” over the F-5. The SSA also assessed ATAC’s technical risk as “slightly lower” than the other offerors because the firm had “only a few insignificant modifications to perform on their aircraft.” In addition, ATAC’s past performance was deemed “more advantageous” than TacAir’s “non-relevant” past performance.

With respect to price, the SSA documented TacAir’s “pricing strategy” and noted that the firm’s strategy was “the primary cause of the significant positive price delta with the other offerors.” Ultimately, the SSA concurred with the SSAC that TacAir’s proposal represented the best value to the agency. In reaching this conclusion, the SSA noted that while ATAC had an advantage over TacAir under one of the nine technical elements (aircraft performance requirements), all other technical elements were considered “essentially equal for all offerors.” He concluded that TacAir’s “very significant positive price delta . . . far outweigh[ed] the sum of the value of the relative performance benefits of the other offerors and the evaluated past performance advantage of two of the three other offerors.”

This decision is really a larger deal than it appears to be at first glance. The Navy went for the cheapest possible option to provide something akin to a 4th generation threat capability and sacrificed performance by way of allowing an upgraded third-generation fighter of a known commodity to take on the role. In other words, the bargain deal won here, and as we mentioned earlier, that is a glaring trend as of late when it comes to Pentagon procurement.

With a multitude of commercial adversary support contracts on the horizon, it will be interesting to see if similar strategies prevail and how much excessive low-bidding will become a tactic to buy market share and establish certain relationships with various customer commands.

The reality is that the F-5 is nothing near to an F-16 when it comes to many aspects of air combat capability. But for beyond visual range applications, aside from a larger radar aperture, an F-5 equipped with a modern radar offers one hell of a bang for the buck without losing all that much in terms of what the enemy looks like to the fleet aviator training against it.

The F-5’s small size, both in terms of radar cross section and especially its visual signature, also gives it something of an advantage over the F-16 for this specific mission set. But there is no doubt, the F-16 is a far superior platform that possesses a whole other level of kinematic performance over the F-5, especially in the within visual range fight. That being said, those facts just didn’t provide enough of an edge to make it worth paying over double the price for the same basic services.

One has to wonder if ATAC would have been better off putting forward the Dassault Mirage F-1, 63 of which the company has acquired from France to expand and upgrade its aggressor fleet, for this contract instead of the more advanced F-16. The F-1s would have cost less to operate and acquire, would have provided high reliability and decent performance, and the jet can still pack a decent radar. Clearly, ATAC made a highly strategic decision by going with high-end F-16s it didn’t even own for this tender, but in retrospect, it appears to have been the wrong one.

You can be sure that the quickly-expanding commercial adversary air-support industry will use this decision and the results of the protest that came after it to inform their future bids and their choices in regards to the aircraft fleets they are looking to procure.

If the U.S. defense budget contracts after its recent, but possibly short-lived expansion, America’s air arms will be increasingly forced to solve capacity and cost issues by outsourcing. And tighter budgets will likely result in similar prioritization of savings over excess capabilities when it comes to future adversary air decisions.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com