The White House has reportedly issued a memo that would empower U.S. military personnel along the border with Mexico, along with National Guardsmen operating there under federal authority, to directly engage in law enforcement activities and use lethal force if necessary. The decision to employ the military domestically in this way could violate the Posse Comitatus Act, which imposes major restrictions on such activities, but may still be legal through exemptions and other legislation.

Military Times’ Tara Copp was first to report that President Donald Trump’s Administration had actually pursued this course of action, with White House Chief of Staff John Kelly said to have signed a “cabinet order” authorizing the plan late on Nov. 20, 2018. CNN and other outlets had previously reported that Trump might issue an executive order to this effect.

The order gives “Department of Defense military personnel” the authority to “perform those military protective activities that the Secretary of Defense determines are reasonably necessary” to support Customs and Border Protection’s mission along the United States’ southern border, according to Military Times. These tasks could include “a show or use of force (including lethal force, where necessary), crowd control, temporary detention, and cursory search.”

In October 2018, U.S. Northern Command began deploying thousands of personnel from all of the services to provide what is called “Defense Support to Civil Authorities,” or DSCA, along the boundary with Mexico. These missions, which you can read about in more depth here, typically include a host of support functions, including surveillance, construction projects, vehicle maintenance, and static site security.

The ostensible reason for this new operation, initially nicknamed Faithful Patriot, was to help bolster security on the border in advance of the arrival of a large group of migrants from Central and South America. These individuals, who are fleeing violence and high crime in their home countries, had very publicly stated their intention to make their way to the United States and seek asylum. There is no assurance that those claims would be successful and that they would be allowed to remain in the country.

At present, there are approximately 5,900 U.S. military personnel, together with some 2,100 members of the National Guard acting in a federal capacity, conducting DSCA missions on the border. The emplacement of concertina wire along portions of the border, including in areas that already have physical barriers, has been, by far, the most visible of those activities.

“Short term, get the obstacles in,” is how Secretary of Defense James Mattis described the goals of the operation during a visit with troops deployed on the border on Nov. 14, 2018. “Longer term…it is somewhat to be determined.”

The long-term mission now appears to encompass the authority to conduct actual law enforcement activities, including detaining immigrants who cross illegally and employing potentially lethal force if necessary. U.S. Northern Command does have standing Concept of Operations Plans (CONPLAN) outlining how it conducts DSCA missions and how it would proceed with more active missions.

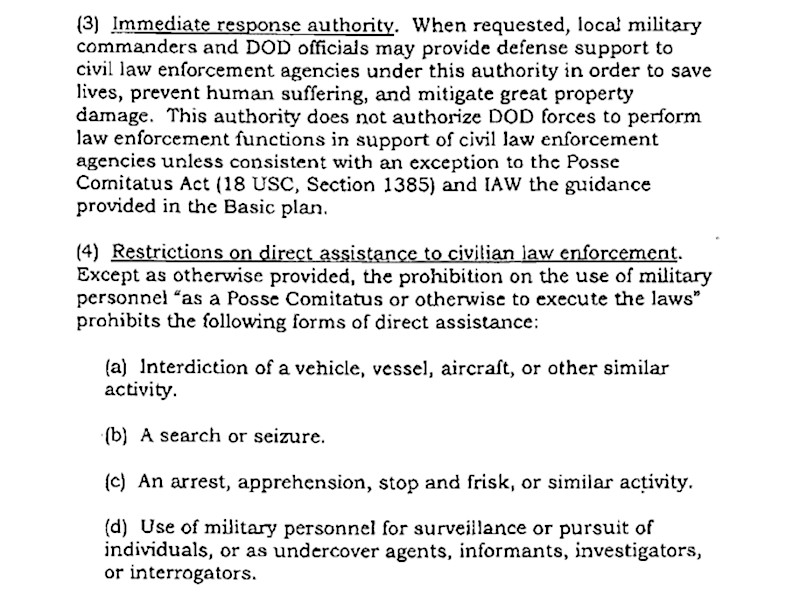

CONPLAN 3501 covers DSCA tasks specifically, but notes the prohibition on troops taking an active law enforcement role “except as otherwise provided.” CONPLAN 3502, Civil Disturbance Operations, sets out the basic parameters for responding to the breakdown of law and order during a major domestic crisis.

But this has already created serious legal questions. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which has received multiple amendments since then, expressly forbids the deployment of U.S. military personnel domestically for these purposes, “except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress.” The question becomes whether the Trump Administration will invoke the president’s inherent right to defend the national security of the United States as enshrined in the Constitution as justification.

This seems very likely, given that Trump himself has claimed that there are terrorists and violent gang members within the group of migrants heading toward the border, though without providing any evidence. Leaked military planning documents for Operation Faithful Patriot said that the likelihood of such threats emerging was low.

The president’s administration has also zeroed in on the size of the so-called “caravan,” saying that the migrants’ plans to cross into the United States en masse threatens to undermine the basic integrity of American border controls. Though immigrants have overwhelmed the capacity of certain detention facilities, a result of Trump Administration policies, there is no indication that the latest group of migrants present a unique concern in this regard.

The Trump Administration could also invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807, which has also seen subsequent amendments, but which legal precedent indicates offers a standing exemption to the provisions of the Posse Comitatus Act. The latest revision to this law, which came in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and that every governor in the United States at the time opposed, gives the president authority to deploy troops to respond to “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” that “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.”

Trump, along with the Departments of Homeland Security, Justice, and State have all at times implied that the organization of a caravan with the goal of mass entry into the United States is, in of itself, in some way illegal, though they have not provided a clear justification for those claims. The Trump Administration recently sought to suspend the right for any individual to seek asylum anywhere but a designated border crossing. A federal judge blocked the implementation of that order on Nov. 19, 2018, pending further hearings.

The last time a president invoked the Insurrection Act was in 1992, when President George H.W. Bush authorized the deployment of U.S. Army and Marine personnel to help quell rioting in Los Angeles following the acquittal of police officers involved in the brutal beating of Rodney King. White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, then-commander of the Marine’s 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, was involved in that operation.

It seems almost inevitable that opponents of this plan will seek to push back against it in federal court, as they have with regards to other executive actions from the Trump Administration regarding immigration issues. Congress could seek to block the new authorities or otherwise modify the provisions of the Posse Comitatus Act or the Insurrection Act, as well.

There is no guarantee that the Department of Defense would seek to make use of the new authorizations, either. The ability to use lethal force, even in self-defense, during domestic operations is, understandably, a sensitive issue within the Pentagon.

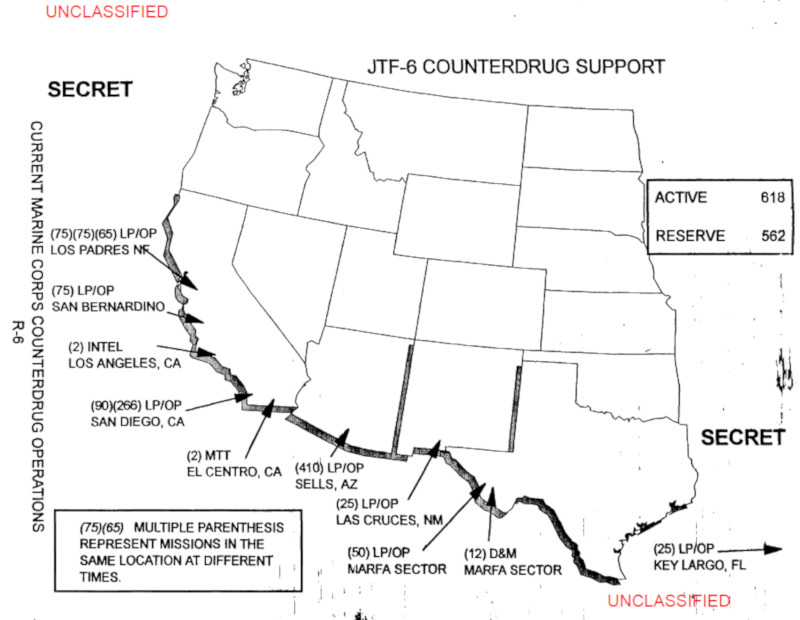

In 1997, U.S. Marines performing a DSCA counter-drug trafficking surveillance mission shot and killed 18-year old Esequiel Hernández Jr., a U.S. citizen who was tending to his goats. Believing the teenager, who was armed with a .22 caliber rifle, may have been there illegally, they had asked members of what was then simply the U.S. Border Patrol to come and assess the situation.

While waiting, Hernández reportedly fired his gun in the direction of the Marines, likely to ward off a predator, prompting them to return fire. A Grand Jury decided not to indict any of the four members of the Marine Corps patrol, but the U.S. government did pay out nearly $2 million to settle a resulting civil lawsuit.

There have been concerns that similar incidents might occur if the Trump Administration loosens the rules of engagement for military personnel along the border. Trump has already suggested that American security forces could treat migrants throwing rocks as equal threats to individuals with guns, and respond accordingly. The president later backtracked on those comments.

“There has been no call for any lethal force from DHS [Department of Homeland Security],” Mattis told reporters at a Pentagon news conference later on Nov. 21, 2018, clearly trying to downplay these worries. “There is no armed element going in. I will determine it, based on what DHS asks for and a mission analysis.”

“Relax. Don’t worry about it,” he continued. “They’re not even carrying guns for Christ’s sake.”

It is possible that this issue may soon become moot. Unless Trump orders an extension to the mission, the military border security operation is set to end entirely on Dec. 15, 2018. Reports have indicated that commanders are looking to send some units back to their home stations earlier than that, too.

The first members of the migrant caravan began to arrive in Tijuana, Mexico ahead of the planned crossing into the United States earlier in November 2018. Some residents in that city, which sits on the border with California, have protested the arrival of the immigrants, saying it burdens their infrastructure and brings the risk of increased crime.

Whether or not these individuals ultimately choose to cross the border in large numbers, and what sort of American security response will be waiting for them, remains to be seen.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com