Earlier in 2018, Scaled Composites, an aviation company well known for its advanced and novel designs, and now a division of Northrop Grumman, quietly posted a series of previously unreleased images online of a stealthy reconnaissance drone called the Scarab. Decades earlier, Scaled had built an initial batch of the unmanned aircraft on behalf of what was then Teledyne Ryan Aeronautical, who, in turn, sold them to just one customer, Egypt.

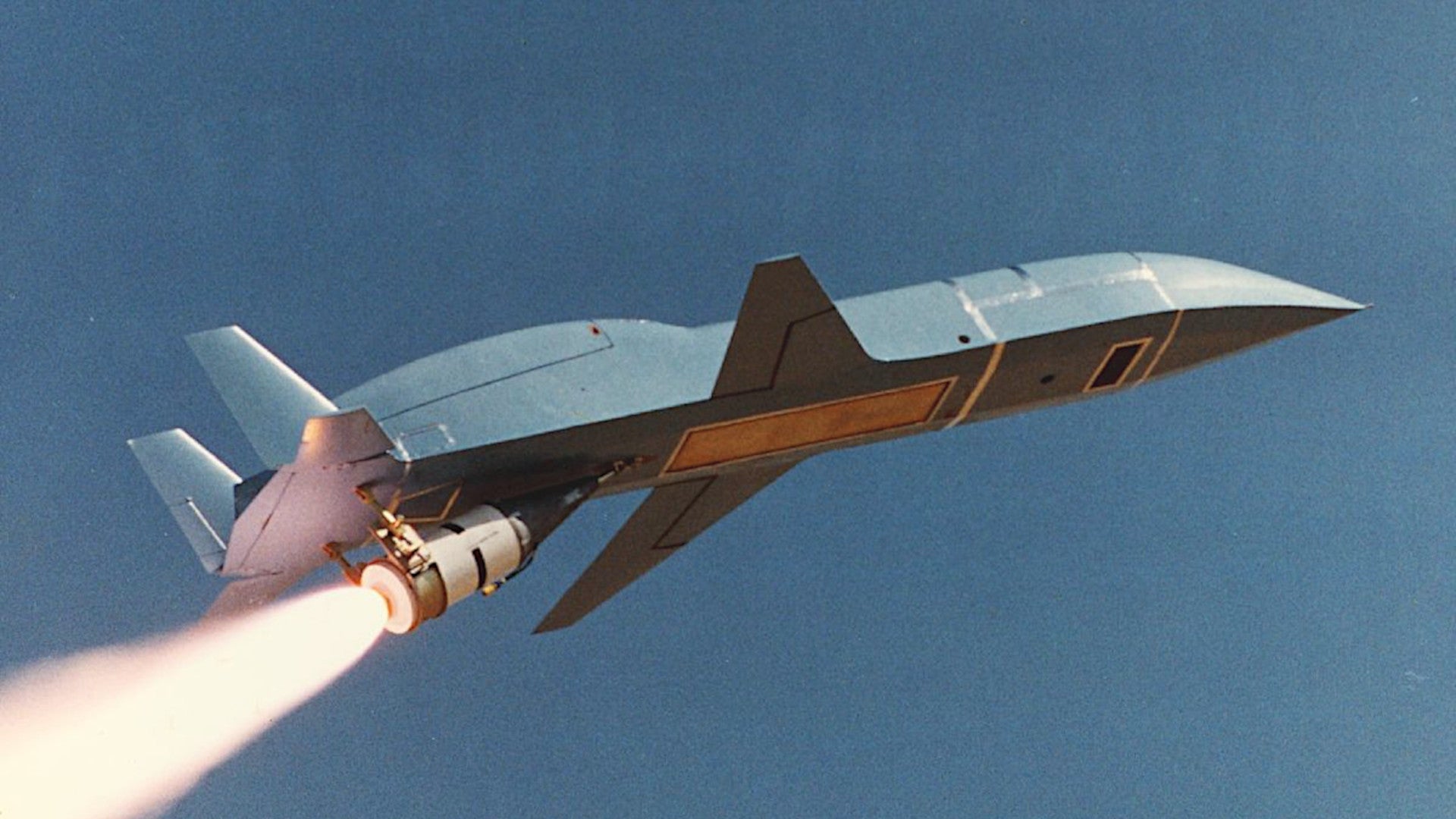

Teledyne Ryan, which itself became part of Northrop Grumman in 1999, developed the jet-powered, ground-launched Scarab, also known as the Model 324, specifically to meet Egyptian requirements in the early 1980s. Scaled was directly involved throughout the entire design and flight test processes.

It’s not entirely clear what the specific impetus was for Egypt’s interest in the drone was, but in 1978, then-Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had signed the Camp David Accords with then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. This led to a formal peace treaty between the two countries the following year. It also came along with a pledge by the United States, which had mediated the deal, that it would provide both countries with significant amounts of often advanced military aid.

To this day, these two countries are among the top recipients of American foreign military assistance. Scarab could have been attractive to the Egyptians as it would have provided an advanced aerial reconnaissance tool that would have been highly survivable against most, if not all of the air defense threats in the broader Middle East region at the time. This means that it could collect details imagery of enemy positions without the need for air superiority to ensure its survival.

The Scarab was definitely a state-of-the-art design at the time with a purpose-built stealth shape. Teledyne Ryan already had years of experience experimenting with stealthier drone designs for the U.S. Air Force, including the AQM-91 Firefly, also known as Compass Arrow, and YQM-98A, or Compass Cope.

The Model 324 also featured a lightweight composite airframe, which helped improve its performance and further reduce its radar cross-section. Export laws prevented Teledyne Ryan and Scaled from using carbon fiber, so the latter firm devised a novel “composite sandwich panel structure with fiberglass and Kevlar for skins and PVC foam cores,” according to Scaled’s website.

“Even with these lower-performance materials, Scaled engineering a wing that was strong and stiff enough to accommodate all of the required flight loads,” the company’s profile on the drone continues. “In fact, the vehicle experienced an extreme negative g pitch-over due to a control problem on the first flight, and did not fail any composite components during the ensuing out-of-control event.”

Other components of the unmanned aircraft proved extremely durable, as well. This was in part a result of the need for the drone to survive being repeatedly blasted into the air from a ground-based launcher using a modified rocket booster from a Harpoon anti-ship missile.

“On one occasion, the 18,000 pound-thrust launch rocket motor exploded at launch and pitched the vehicle approximately 10 feet vertically into the air,” Scaled’s website notes. “The vehicle then fell back into the incinerating launcher and bounced out into the desert. The integrity of the fuel tank was not compromised during this event.”

The entire system included a truck-mounted ground control station and power generation system that also served as the prime mover for the trailer-mounted launcher. It’s not clear who built the 8×8 all-wheel-drive truck, but it appears to have an independent suspension system very reminiscent of a family of designs the Standard Manufacturing Company was developing at the same time. The U.S. military tested a variety of the Standard Manufacturing vehicles, including a wheeled self-propelled anti-aircraft gun called Excalibur, but never adopted any of them.

The six-wheeled trailer also had an auxiliary motor to allow crews to more readily move it into its actual launching position when detached from the truck. The truck-and-trailer combination had a maximum speed of 52 miles on improved roads, but also had some off-road capability. A complete system with a Scarab on the launcher was also small enough to fit inside a C-130 cargo plane.

After blasting off from its launcher, Scarab could reach a top speed of nearly 650 miles per hour and an altitude of up to 40,000 feet, depending on its predetermined altitude and mission profile, and could carry a payload of more than 250 pounds over a total distance of 1,400 miles. When it returned to base, its small jet engine would cut out and a parachute would deploy. The drone would eventually sail down to earth, landing on a set of inflatable airbags hidden inside the fuselage and wings.

Crews on the ground had a line-of-sight command link that they could use during the beginning and end of the drone’s flight. Beyond the range of that control station, the drone would use pre-programmed waypoints and an inertial navigation guidance system to get to and from the intended area. Later on, Egypt upgraded the Scarabs with a GPS-assisted guidance capability.

As delivered, the Scarabs could carry either a KS-153A optical camera or a Loral D-500 infrared laser camera system. The latter used the laser for infrared illumination, allowing the camera to capture images at night. Both cameras, however, employed wet film that required processing after the mission was over. The drone could not transmit any imagery back to base during flight.

Egypt’s President Sadat, who was assassinated in 1981, never got to see the Scarabs and almost certainly didn’t initiate the program. Scarab’s first flight occurred in 1987 and Sadat’s successor, President Hosni Mubarak, accepted the first examples the following year.

Scaled Composites built a total of 29 Scarabs for Teledyne Ryan, which shipped them to Egypt and trained members of the Egyptian Air Force how to fly them. Teledyne Ryan built another 30 Scarabs independently as a second-run and delivered those to Egypt as well. It was the first time Teledyne-Ryan had exported an unmanned aircraft of any kind, which the U.S. military had not adopted, to a foreign country. The Egyptians only established one unit to operate the drones at Kom Awshim Air Base, approximately 50 miles south of Cairo.

In 1988, the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marines did join together to develop an air- and ground-launched derivative that could be employed both as a target drone and an unmanned reconnaissance platform. Unfortunately, in 1993, the Navy and Marines dropped out of the program.

The Air Force could not afford to purchase the drones, then known as the BQM-145A Peregrine, by itself and subsequently canceled the entire project later that year. The Peregrines lack the visually distinctive hump the Scarabs have on top of their rear fuselage, with their twin air intakes being arranged pectorally instead of having a single intake mounted dorsally.

Of the 59 Scarab drones the Egyptians received, they reportedly never even uncrated 50 of them, according to Scaled. The nine operational examples did fly some 65 operational missions, but there’s no information about what areas they flew over or for what purpose. There are reports that during Operation Desert Storm, the U.S.-led coalition considered asking the Egyptians to commit the Scarabs to help increase overall reconnaissance coverage. True or not, the conflict ended before the drones went to work, though.

Regardless of their operational activities, the delivery of the drones to Egypt caused something of a stir inside and outside the United States. The biggest concern was that Egyptians might try to modify the Scarabs into stealthy ground-launched cruise missiles that could have presented a significant threat to other countries in the region and potentially have a destabilizing effect.

The Missile Technology Control Regime, a voluntary arms control arrangement covering missiles and unmanned aircraft, which was in place at the time, only prohibits the export of systems that can carry a payload of more than 1,100 pounds to distances greater than 185 miles. This would not cover the Scarab with its stated payload capacity, though it might be possible to increase the payload at the cost of overall range. Either way, Teledyne Ryan did not sell Scarabs to any other customers.

The exact status of the remaining Scarabs is unclear. As of the late 1990s, Teledyne Ryan was still actively supporting the program in Egypt. After Northrop Grumman bought the firm in 1999, it took over that support contract.

“We are working on a contract with the Egyptians to do upgrades on that aircraft, we are negotiating that as we speak,” Rick Ludwig, then-Director of Unmanned Systems Business Development for Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems, told FlightGlobal in 2006. “They still fly that aircraft about once a month.”

The next year, Northrop Grumman said it was still in talks with Egypt over potentially upgrading the Scarabs, to include new guidance systems and sensors. The addition of digital still or video cameras and a two-way satellite data link to send that imagery back to base in near real time could have significantly improved the drone’s capabilities.

The video below includes footage of a Scarab during testing, beginning at 5:33 in the runtime, followed by clips of the air-launched BQM-145A Peregrine.

There’s no clear evidence that that upgrade program ever went forward and it may have eventually ended up hampered by political developments. In 2011, Egypt experienced mass protests that led to the ouster of President Mubarak the following year. Then, in 2013, the Egyptian military launched a coup and took power from the subsequent democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi.

President Barack Obama subsequently put a freeze on military aid to the country, but lifted those restrictions in 2015. President Donald Trump’s administration has continued re-establishing military ties with the country and has also advocated for increased American arms sales abroad in general.

At this point, the Scarabs, many of which may have been sitting in storage for decades, may be too expensive and impractical to modernize and put to more active use. The idea that the Egyptian Air Force was only flying one of these drones once a month a decade ago doesn’t suggest it was particularly invested in retaining anything but a token capability.

All told, the Scarab’s story may end in relative obscurity. Of course, there’s always the chance that someone might uncover one of them in the future still in its crate sitting in an Egyptian warehouse and hopefully send it to a museum.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com