Barring a dramatic shift in present U.S. government attitudes on the matter, it appears that President Donald Trump and his administration are about to unilaterally pull the United States out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, commonly known as the INF. U.S. authorities have long accused Russia of violating the deal, but eliminating the agreement altogether could have serious and far-reaching ramifications. There’s little guarantee that the United States will see clear benefits from the plan, which could quickly prompt a destabilizing arms race and create another serious point of contention between the U.S. government and its allies, especially in Europe.

Trump publicly announced his administration’s intent to withdraw from the INF during a political rally in Elko, Nevada, on Oct. 20, 2018. Reports indicating that the treaty was on its last legs had first emerged on Oct. 19, 2018. National Security Adviser John Bolton, who has long opposed the deal and other arms control agreements, appears to be the biggest proponent of the plan, which the U.S. government has yet to formally announce.

“Russia has violated the agreement. They have been violating it for many years,” Trump told supporters at the gathering in Elko. “And we’re not going to let them violate a nuclear agreement and go out and do weapons and we’re not allowed to.”

On Oct. 22, 2018, Bolton touched down in Moscow for a visit where many expected he would inform his Russian counterparts about the United States’ decision to leave the INF. It’s unclear whether Trump’s announcement was planned or not and whether that might have upset his administration’s plan for terminating U.S. participation in the treaty.

Russian television aired a candid conversation between Bolton and Russian President Vladimir Putin, as well as a brief press conference, ahead of a meeting between the two men on Oct. 23, 2018. Trump’s National Security Advisor confirmed the administration’s plan to withdraw from the INF, but said that the U.S. government had not yet submitted the formal withdrawal notice.

“As far as I can remember, the U.S. seal depicts an eagle on one side holding 13 arrows, and on the other side an olive branch with 13 olives. … Here’s the question: Did your eagle already eat all the olives and only the arrows are left?” Putin asked Bolton on camera. “Hopefully, I’ll have some answers for you. But I didn’t bring any more olives,” Bolton responded.

“That’s what I thought,” Putin retorted. Bolton reportedly laughed at this.

What is the INF?

Despite its name, the INF, which entered into force in 1988, bans the possession of any ground-launched conventional or nuclear-capable missile of any type that can hit targets between 310 and 3,420 miles away. It does not prohibit air- or sea-launched weapons in that range bracket and does not ban land-based research and development of missiles that fall within its prescribed limits.

The treaty was unprecedented in many ways, doing away with an entire category of weapons. The Soviets and the United States agreed to scrap eight different types of missiles in total and to allow for a decade’s worth of on-site inspections to verify compliance.

The U.S. military did away with its Pershing Ia short-range ballistic missiles and Pershing II medium-range ballistic missiles, as well as the BGM-109G Gryphon ground-launched version of the Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile. The Soviets dismantled their SS-4, -5, -12, -20, and -23 short-, medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. The road-mobile SS-20 was a particular focus of the INF, as the United States felt its range and multiple warheads combined with its ability to rapidly reposition itself before launch made it a particularly destabilizing threat.

It also ended public development of the SSC-X-4, a ground-launched nuclear-capable cruise missile. The Russians did continue work on a sea-launched version of this weapon. The Kalibr sea-launched cruise missile is derived from that design, which in turn may have served as the basis for another missile known as the SSC-8.

What’s the problem?

The U.S. says that Russia is in violation of the deal through the deployment of a banned nuclear-capable land-based cruise missile known variously by U.S. government nomenclature as SSC-8, the Russian designation 9M729, and the NATO codename ‘Screwdriver.’ Russia has denied that this weapon system even exists, but it does have ground-based Iskander-M quasi-ballistic missile and Iskander-K cruise missiles, which have stated ranges right at the edge of the INF limits.

In turn, Russia has accused the United States of failing to uphold the deal through the establishment of the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense site in Romania. The U.S. is working on building another such facility in Poland. The U.S. government has dismissed these claims, saying that the Mk41 vertical launch system launchers the Aegis Ashore uses are not compatible with any missile other than the SM-3 interceptor and that the sites do not have the associated fire control and targeting systems required to launch an INF-banned weapon. It’s worth noting, that on American destroyers and cruisers, a version of the Mk 41 system does deploy the BGM-109 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile.

Bolton and other critics of the INF argue that if Russia is in violation of the treaty and has no intention of returning to compliance, that the U.S. military is at a distinct disadvantage by continuing to abide by the agreement. In addition, the United States already has to contend with other countries, most notably China, which do not have follow the deal’s terms at all.

“We have no ground-based capability that can threaten China because of, among other things, our rigid adherence, and rightfully so, to the treaty that we sign onto, the INF treaty,” U.S. Navy Admiral Harry Harris, then head of U.S. Pacific Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2018. “Over 90 percent of China’s ground-based missiles would violate the treaty,” he had told the House Armed Services Committee the month before. Harris, who is now U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, has developed a close relationship with Trump.

These are valid arguments in principle. If Russia is in violation of the INF, there have to be penalties of some sort, or else the point of having the deal at all is moot. At the same time, the U.S. military following the terms of the INF has indeed left it without any weapons in this category.

Weapons with limited utility

The real question, however, is whether or not the absence of those weapons puts the United States at as much a strategic disadvantage as Bolton and other critics of the INF would suggest. As noted, the treaty has not limited the development of air- and sea-based missile systems within the prescribed range and also does not prohibit land-based systems with ranges greater than 3,420 miles, leaving the U.S. military with other conventional and nuclear deterrent options.

“There are no military requirements we cannot currently satisfy due to our compliance with the INF Treaty,” U.S. Air Force General Paul Selva, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told members of the House Armed Services Committee in 2017. “While there is a military requirement to prosecute targets at ranges covered by the INF Treaty, those fires do not have to be ground-based.”

Selva did say that INF-banned systems would improve the “flexibility and the scale of our intermediate-range strike capabilities,” but did not note whether or not a weapon system in breach of the treaty was the only way to provide that capability. The U.S. military has significant air-launched conventional and nuclear-tipped cruise missiles and sea-launched cruise missiles with conventional warheads that have similar ranges to systems the treaty banned, but are compliant with the agreement. In terms of nuclear deterrent capability, there are also ground-launched and submarine-launched nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, as well as stockpiles of nuclear gravity bombs.

At present, the United States is developing a new nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missile, modified sea-launched nuclear-armed ballistic missiles with “low-yield warheads,” and is investigating the potential of fielding a nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile. The latter two weapons are understood to be aimed at countering Russian INF-violating systems.

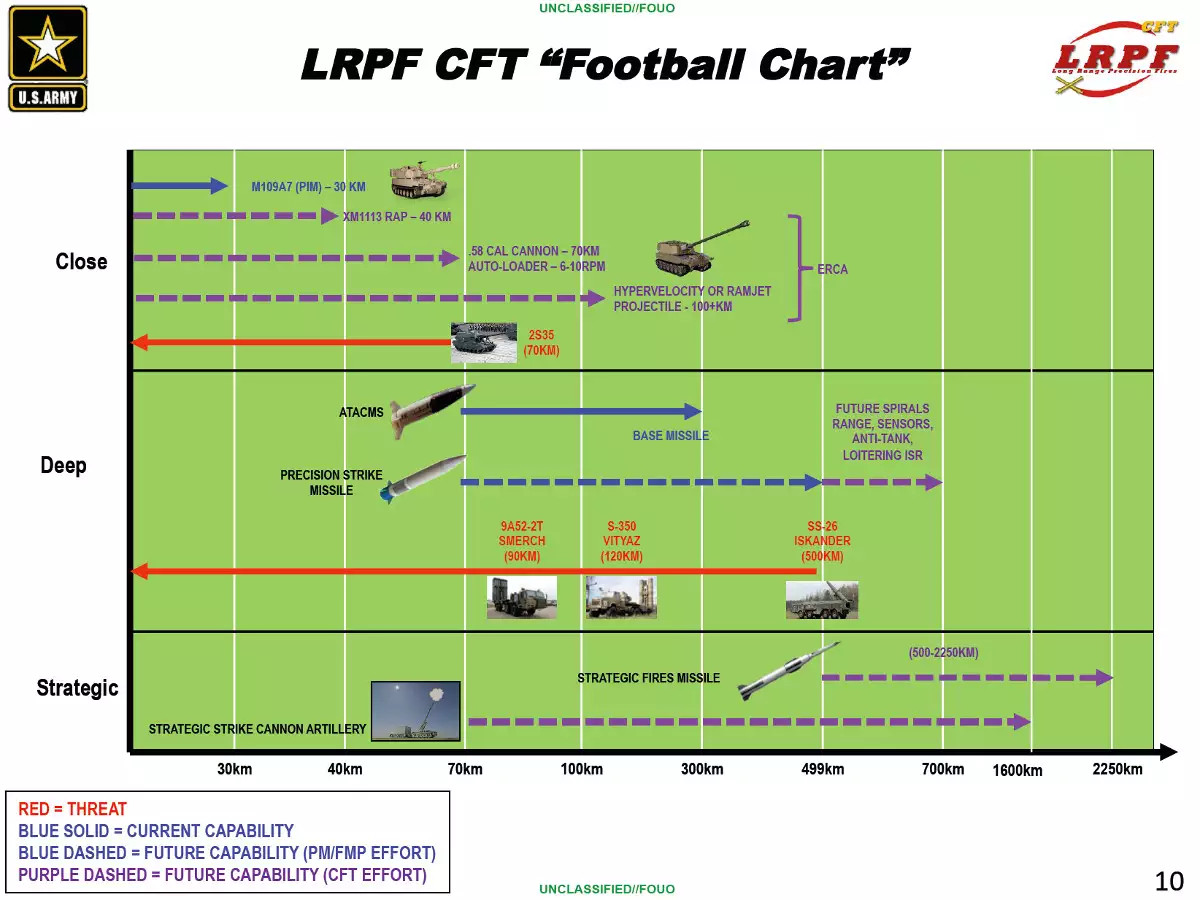

The U.S. military is also pushing ahead rapidly with air-, sea-, and ground-based hypersonic weapons, all of which will offer prompt strike options on short notice against time-sensitive and highly defenses targets, potentially including Russian SSC-8 batteries. The U.S. Army is also developing its own plans to field a new quasi-ballistic missile that has a range that is right below the low end of the INF’s range restrictions, as well as railguns and superguns with extended range capabilites that the treaty doesn’t cover at all.

Even if the U.S. government has determined that this layered array of options would not provide sufficient deterrents against Russia’s employment of its INF-breaching missiles, or to Chinese or other foreign systems not subject to the treaty, a comparable U.S. system might not be a realistic answer. By their very definition, the land-based systems the deal covers are “intermediate range” in nature, which would require them to be forward deployed in the same general region as their intended targets.

The United States has limited options when it comes to using its own national territory for this purpose and there is no guarantee that the United States would be able to secure approval from allies and partners to deploy nuclear-capable intermediate-range weapons onto their soil, or in the case of many European countries re-deploy these types of missiles, which would immediately make them a target during any potential conflict and could prompt domestic protests. This would apply equally to U.S. allies both in Europe and in the Pacific region.

Far-reaching effects

Though often described as a bilateral deal between the United States and Russia, the INF isn’t just about those two countries. The Soviet Union, not Russia, signed the INF, and Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine all continue to honor it despite now being independent countries.

So, eliminating the deal could touch off a major arms race, especially in Ukraine, which is already under significant threat from Russian INF-compliant missiles. The deal has also provided an umbrella of security for smaller NATO members and other American partners in Europe, many of whom might feel the need to develop their own weapon systems or countermeasures or who might simply resent the United States making a unilateral decision. The Trump Administration had reportedly issued an ultimatum of sorts to other members of NATO about the need to come to a consensus about how to approach Russian violations of the INF in December 2017.

Russia needs to “get its house in order,” U.K. Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson said after Trump’s pronouncement in Nevada, adding that his country stood behind the U.S. government’s decision. However, the United States’ apparent decision “raises difficult questions for us and Europe,” German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said. U.S. relations with Germany have been particularly strained under the Trump Administration. Japan, another important American ally, has expressed hope that the INF can be saved.

With all this in mind, the U.S. pulling out of the INF treaty would appear to have, at best, uncertain strategic and deterrent benefits, while running the very real risk of creating unnecessary tensions with allies and touching off destabilizing developments in Europe and elsewhere. Russia has already been working in many ways to weaken the international order and challenge long-standing norms, looking to restrict or otherwise challenge the terms of other important arms control regimens.

At the same time, it has engaged in a broad and carefully coordinated campaign to spread misinformation and disinformation about its opponents, spreading conspiracy theories and blaming its critics for the exact malign activities it stands accused of engaging in. The Kremlin could seize on the U.S. government pulling out of the INF as an opportunity to try and further drive a wedge between the United States and its European allies and partners or at least try and fuel public discontent about the decision to withdraw from the treaty.

On top of that, the Russians could easily finally reveal the SSC-8 as a “new” system developed in response to threats from the United States, giving them an opportunity to try and seize the moral high ground with the public deployment of the weapon system that was at issue to begin with. There is already evidence that the Kremlin is moving in that direction in response to the U.S. government’s apparent INF decision.

“The breaking of the INF Treaty’s provisions forces Russia to take measures on ensuring its own security,” Dmitri Peskov, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s top spokesperson, said on Oct. 22, 2018. “If this system [a U.S. missile that doesn’t adhere to the INF] is developed, steps from other countries, and in this case of Russia, on restoring balance in this sphere are needed.”

What happens now?

All this being said, it’s not clear how the United States, or anyone else, can save the INF. Trump and Bolton’s comments, though still not accompanied by the necessary formalities yet, are so definitive as to make it hard to see how the U.S. government can halt the process now or that anyone would want to. If critics argue that remaining party to the deal is farcical if the Kremlin refuses to comply with its terms, then reversing course now could make the U.S. government seem particularly impotent.

The Russians themselves are frustrated by the limits imposed by the INF, especially in regards to China, which shares a massive border with Russia that has been the subject of violent territorial disputes in the past. There is evidence that the development of the SSC-8 was, at least in part, a response to more regional threats, rather than as purely a means to challenge the United States and its allies.

“Nearly all of our neighbors are developing these kinds of weapons systems,” Putin said in 2013. The Soviet Union’s decision to conclude the treaty in the first place was “debatable at best,” he added.

So, there is a good argument to be made that the treaty constrains the Kremlin a lot more than it does the U.S. government, which has the resources to explore alternative weapons. Maintaining the INF, even in its broken form, could provide a bulwark to return to in the future and limits what the Kremlin can do out in the open.

With that in mind, one option that the United States still has for goading the Russians back into compliance would be to find a way to declassify hard evidence of the SSC-8’s existence. So far, the U.S. government has declined to publicly provide significant information on the missile, saying doing so would risk exposing its sources and methods and harm its potential to gather strategic intelligence in the future.

Forcing the issue out into the open could change the nature of the public debate and make clear the extent of Russia’s violations of the INF. Above all else, it could keep Russia from declaring that it is only now deploying the missiles in response to the U.S. unilateral withdrawal from the treaty. The United States could strongly reiterate its own compliance by inviting neutral, third-party weapons inspectors to verify that the Aegis Ashore launchers cannot fire banned missiles.

Pulling out of the INF could have cascading effects on other treaties, as well. The U.S. and Russia will have to begin negotiating whether to extend the New Strategic Arms Control Treaty, or New START, which sets limits on various strategic nuclear weapons. That deal, which you can read about in more detail here and here, is set to expire in 2021 unless the two parties can agree on extending it, a possibility that seems increasingly questionable.

The full extent of the impact of the end of the INF probably won’t be apparent for some time. But since the U.S. government has been preparing for the potential collapse of the treaty over Russia’s violations since at least 2013, it might not take long for it to begin implementing any of its own contingency plans once the Trump Administration formally withdraws from the deal.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com