In what may be one of the most important reports I have read in a long time, David Larter of Defense News lays out an incredibly inconvenient reality for Military Sealift Command and its fleet of cargo ships and the Merchant Marines that operate them—in the next big conflict they are likely to be left to fend for themselves without any protection from U.S. Navy vessels. This is an especially troubling proposition considering roughly 90 percent of the Army’s and Marine Corps’ materiel will be relegated to transport on the high seas during such a crisis.

In Larter’s piece, which you can and should read in full here, he talked at length with Mark Buzby, a retired Rear Admiral who now heads up the Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration. His comments were both frank and unnerving:

“The Navy has been candid enough with Military Sealift Command and me that they will probably not have enough ships to escort us. It’s: ‘You’re on your own; go fast, stay quiet.’

…

Adm. Mewbourn at Military Sealift Command and I have talked a lot about this and we have been trying to get the word out to people that we are going to have to do things differently… Turn your navigation lights off, turn your [Automatic Identification System] off, turn your radars off, tell your crews not to use their cell phones — all those [Emissions Condition] things that we in the Navy are familiar with that are completely foreign to a merchant mariner and are seen as an imposition.

…

But it harkens back to some of the hard lessons we learned in World War II where in 1942 the Germans were sinking us left and right.

Even some of the equipment that’s on ships now automatically transmits data… We put new cargo-control consoles on our Kaiser-class oilers at MSC, and one of the things we discovered soon after was that those things are talking constantly.

…

The last bullet point on one of the slides is ‘Learn how to swim… It’s to that point. There’s not going to be a bunch of destroyers around us as we take those ships over there. We’re going to be hitting the sea buoy, cranking it up and going hell-bent for leather, hoping to stay undetected.”

You are probably thinking ‘but one of the Navy’s most important jobs is supposed to be keeping critical sea lanes open and to provide convoy duty to support a war effort?’ You are right, but that’s not where the Navy’s priorities have lied over the last two and a half decades or so. It’s a density and priority problem.

The Navy does not have enough surface combatant with particular capabilities to fight a high-end conflict and provide convoy duty for what would be a massive sealift operation. And clearly, America’s would-be opponents have recognized this Achilles heel, just as they have with vulnerabilities in U.S. combat doctrine in the air. Simply put, it’s much easier to kill a brigade of armor by sinking it in the middle of an ocean than facing it head-on.

This truth also fits with what many of us have been pounding away at for the better part of a decade or more—that the Navy’s misguided investment in Littoral Combat Ships could end up being a very bloody and strategically damning mistake. These lightly armed and even more lightly armored vessels have suffered from low availability rates, are now only capable of focusing on one key mission and lack any sort of area air defense capability at all, not to mention the range and seakeeping of more traditional surface combatants. In other words, the Navy needed a modern multi-role frigate that can handle escort duty during a time of war yesterday. A ship that can tackle lower volume threats below, on, and above the surface of the water and persist over long ranges and in heavy sea states.

That ship is finally in the works now under the FFG(X) program that intends to field its first operational frigates by around 2025. The Navy should put even more emphasis on speeding it up and expanding the program in order to reach better economies of scale that will make it as affordable as possible to procure large numbers of hulls.

Having multi-role capable escorts is key as it’s not as if the threat to maritime convoys will come from one domain exclusively. Submarines may pose the most traditional danger when it comes to moving lines of supply vessels across the open ocean, but they don’t just launch torpedoes or lay mines. They can also fire anti-ship cruise missiles and some of them can sling dozens of them at a time. As such, a single adversary platform can represent a layered threat.

Aircraft and surface combatants are also clearly an issue. As such, an escort ship has to be able to counter a multitude of threats that could attack suddenly from a number of vectors, not just one. This means anti-submarine, anti-air, and anti-surface warfare capabilities are needed, otherwise, multiple assets would have to be assigned to do the same mission. In addition, there aren’t enough multi-billion dollar destroyers to fulfill the demands the Navy already has, let alone those that will be required during a time of war. Assigning these high-end combat ships to convoy duty isn’t just wasteful, it will likely be impossible.

Larter also points out that manpower is also a major issue that could leave America’s total force with a gutted logistical train during a time of war, he writes:

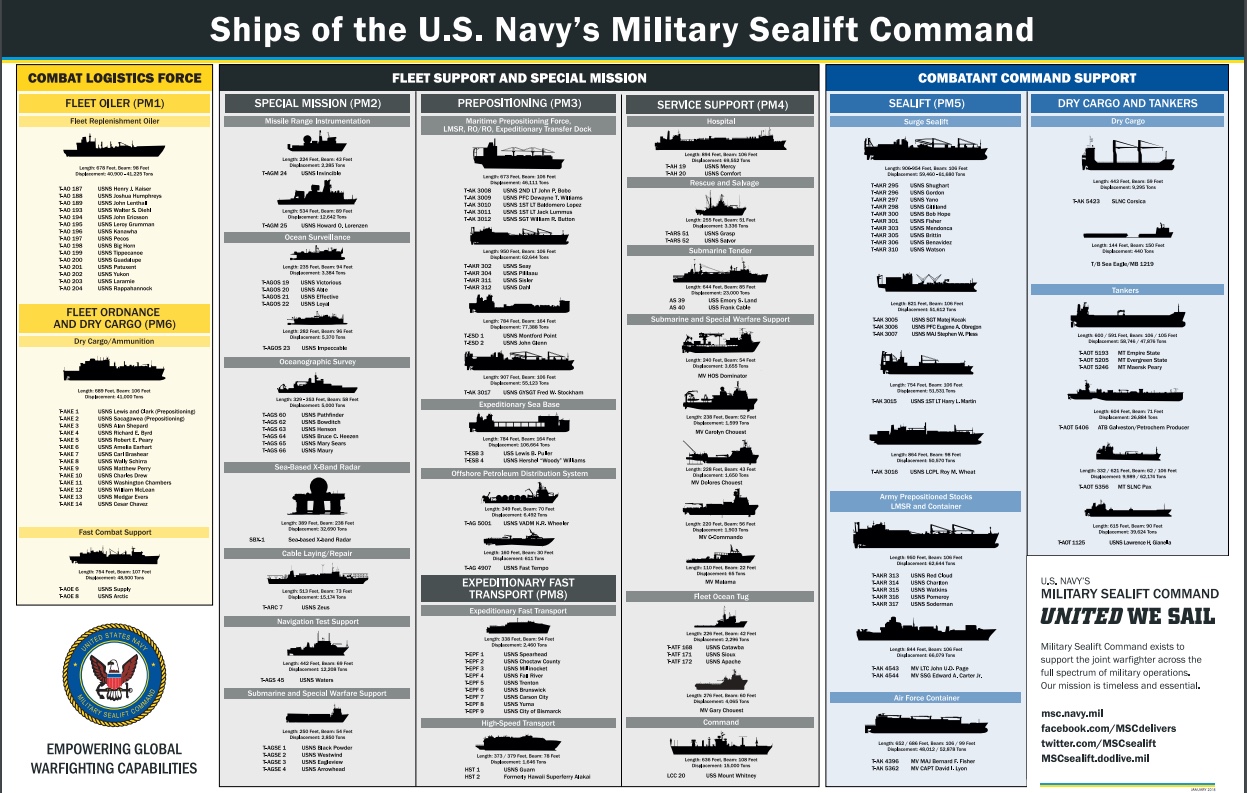

“Today, the Maritime Administration estimates that to operate both the surge sealift ships — the 46 ships in the Ready Reserve Force and the 15 ships in the MSC surge force — and the roughly 60 U.S.-flagged commercial ships in the Maritime Security Program available to the military in a crisis, the pool of fully qualified mariners is just barely enough.

They need 11,678 mariners to man the shops, and the pool of available, active mariners is 11,768. That means in a crisis every one of them would need to show up for the surge, according to a recent MARAD report to Congress. In contrast, the U.S. had about 55,000 active mariners in the years prior to World War II, with that number swelling to more than 200,000 at the height of the war, according to most sources.

That means that significant losses among the available pool of mariners would likely dissuade some from volunteering (bad) and would mean the loss of mariners with critical skills needed to operate the fleet for months or even years in a major contingency (worse). And even without losses, MARAD estimates the country is about 1,800 mariners short if any kind of rotational presence is needed.”

He also goes on to discuss some very important lessons learned during WWII and how we may be setting ourselves up for logistical failure in a future conflict.

We reached out to David to get a bit more background on how he came to reporting on this critical but nearly invisible issue, this is what he told us:

“The series I’m working on has been something I’ve been chipping away at over a number of months. It struck me that if the National Defense Strategy calls for preparing for a war with China or Russia or both, the US wouldn’t get very far without a robust sealift capability. Turns out, when you dig into the issue, the US has a serious strategic liability on its hands both in terms of the available workforce for a major surge and, like much of the rest of the military, in aging platforms in need of modernization.

When you layer in the fact that the U.S. Navy is much smaller than it was in the Cold War and would be vital in opening up the sea lanes to move this equipment, responding to a Russian move in Europe or Chinese move in Asia would be very slow going. If the pace of war is speeding up, as CNO often says, this is one place where it seems the US could find itself in a logjam.”

Yesterday, David also reported on the not so great state of Military Sealift Command’s fleet—a significant portion of which still run on steam power—making the possibility of even sustaining a logistics chain across an ocean all that more dubious. In addition, in a tweet he reminded us that airlift is not an alternative as it has major limitations, even when it comes to the USAF’s unique ability to maintain an air-bridge between two disparate locales:

He is completely right. Take Operation Airborne Dragon in 2003. It took 30 C-17 sorties to bring in just five Abrams tanks, five Bradleys fighting vehicles, and a battalion command post, along with the personnel to man those vehicles and facilities. Keep in mind that a single tank company has 14 Abrams main battle tanks. In addition, facilities to even land those aircraft may be next to non-existent during the opening weeks or even months of a conflict—another similar hard reality the USAF is now finally coming to terms with. In addition, Sea bases can pop up virtually anywhere to work as a nexus between MSC’s largest logistics ships and the shore.

Beyond the nuts and bolts of the issue, the bigger picture here seems to be that the Pentagon is in denial of the realities surrounding its ability to rapidly move material across the globe and especially into semi-contested environments. These are supply and demand issues as much as there are survivability ones. The good news is there are solutions to this problem, which includes pumping more funds into the military’s sealift ecosystem and accelerating and widening procurement of FFG(X), but it also could include providing some organic defenses to Military Sealift Command associated ships themselves.

Containerized weapon systems are especially attractive for such applications. Some Military Sealift Command ships had Phalanx close-in weapon systems, but most, if not all now do not. Installing a more advanced but modular point air defense capability, such a containerized version of SeaRAM, would provide a robust last-ditch defense against aerial and some surface threats. Anti-submarine warfare is a much tougher nut to crack, but even modular torpedo defense systems, both active and passive, could be deployed in a similar role but to counter attacks from below the waves. Some of MSC’s most advanced ships have Nixie decoys, but others do not.

Finally, electronic warfare can go a long way in providing an affordable screen against certain kinds of attacks and from being detected by the enemy in the first place, all without actually arming cargo ships with additional kinetic weaponry. In fact, just the situational awareness the latest maritime electronic warfare systems provide could go a long way when it comes to MSC ships’ survivability, as avoiding threats is maybe the best defense of all. Expendable decoys could also be paired with an electronic warfare system, giving these big vessels a much better chance of averting an anti-ship missile strike than they have now.

It’s also worth noting that the Navy has already been eyeing outfitting some of its logistics ships with bolt-on weapon systems, including cruise missiles, as part of a ‘distributed lethality’ model of operations. But adding offensive punch to some of these ships could also work as a valuable deterrent.

Hopefully, Larter’s report will help to push the Department of Defense towards taking such a glaring weakness seriously. Sealift may not be sexy, but without it, America stands little chance in a protracted peer-state conflict overseas.

They say logistics wins wars. If that is so, then the current status quo seems like a great way to lose one.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com