For decades, in spite of their popularity in movies, television, and video games, jetpacks and individual flying platforms have continually proven to be too costly and otherwise ill-suited to military use. But the allure of finally finding a practical system persists and within a month, SOFWERX, a U.S. Special Operations Command-funded public-private partnership that seeks out novel technologies, will finish up testing of Zapata’s EZ-Fly jet-powered personal flying machine.

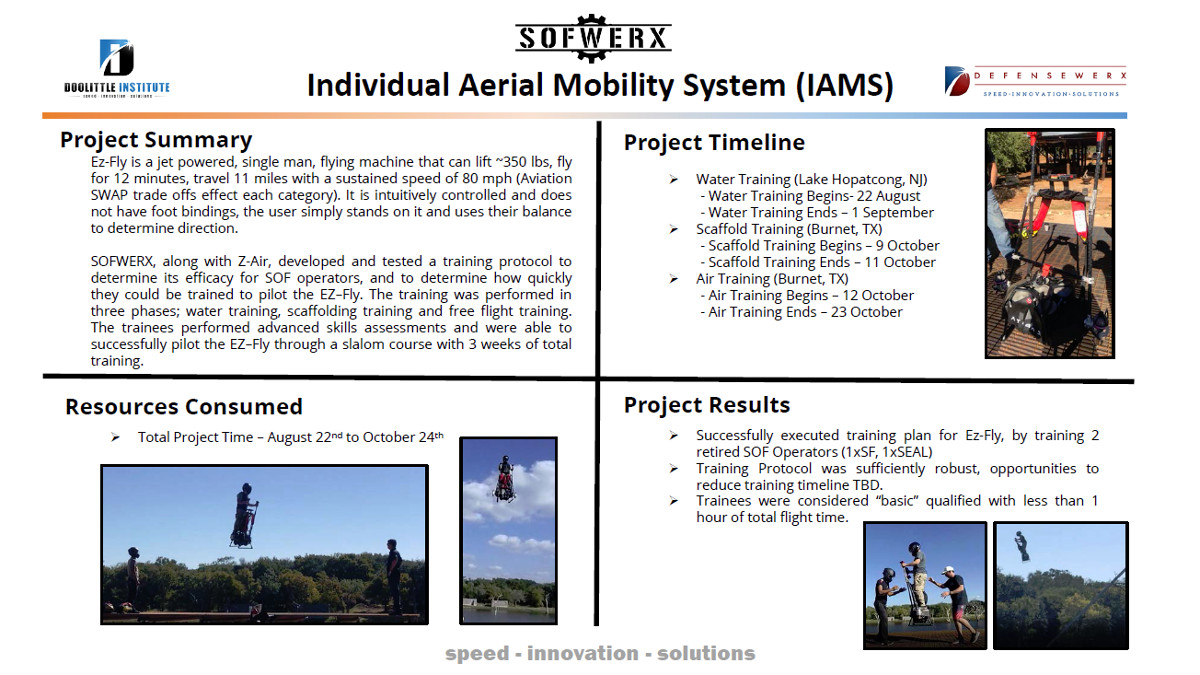

The project, formally known as the Individual Aerial Mobility System (IAMS), began on Aug. 22, 2018, and is set to conclude on Oct. 24, 2018. Initial over-water testing occurred at Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey, before the work moved to Burnet, Texas for more intensive evaluations. The vehicle itself has been in development since at least 2017 and a job offer that year called for two individuals with prior special operations forces (SOF) experience to help Zapata, also known as Z-Air, in crafting the militarized derivative of the company’s Flyboard Air.

After crafting the vehicle itself, “SOFWERX, along with Z-Air, developed and tested a training protocol to determine its efficacy for SOF operators, and to determine how quickly they could be trained to pilot the EZ-Fly,” the Florida-headquartered tech incubator said in an official fact sheet. “The trainees performed advanced skills assessments and were able to successfully pilot the EZ-Fly through a slalom course with three weeks of total training.”

The vehicle itself consists of a platform with seven small, computer-controlled jet turbines, each with their own independent fuel supply. The “pilot” stands on top and uses controls in two sticks, similar in basic appearance to ski poles or those on an elliptical exercise machine, to take off, land, and hover. The operator also uses them, along with the motion of their body, to steer.

Zapata, and its French founder Franky Zapata, already had significant experience with similar systems. The company’s first project was the water-jet powered “hoverboard” called Flyboard, which then evolved into the jet turbine-powered Flyboard Air.

A tablet-sized display mounted between the Fly-EZ’s control sticks provides important information, such as remaining fuel, and offers automated features, such as an automatic hover mode. Zapata says the entire system can carry an individual and their gear with a combined weight of up to 280 pounds, fly a maximum of 80 miles per hour, for up to 12 minutes, and at altitudes as high as around 9,000 feet. One of the vehicles carrying the maximum load is likely to have reduced range, speed, and maneuverability.

The company also says it’s intuitive and safe to use, with the computer-controlled systems providing built-in redundancies and automatic compensation if one of the jet engines fails. “I thought it was a gust of wind,” Henry Berkowitz, one of the two former special operators who now work for Zapata, told CNBC in 2017.

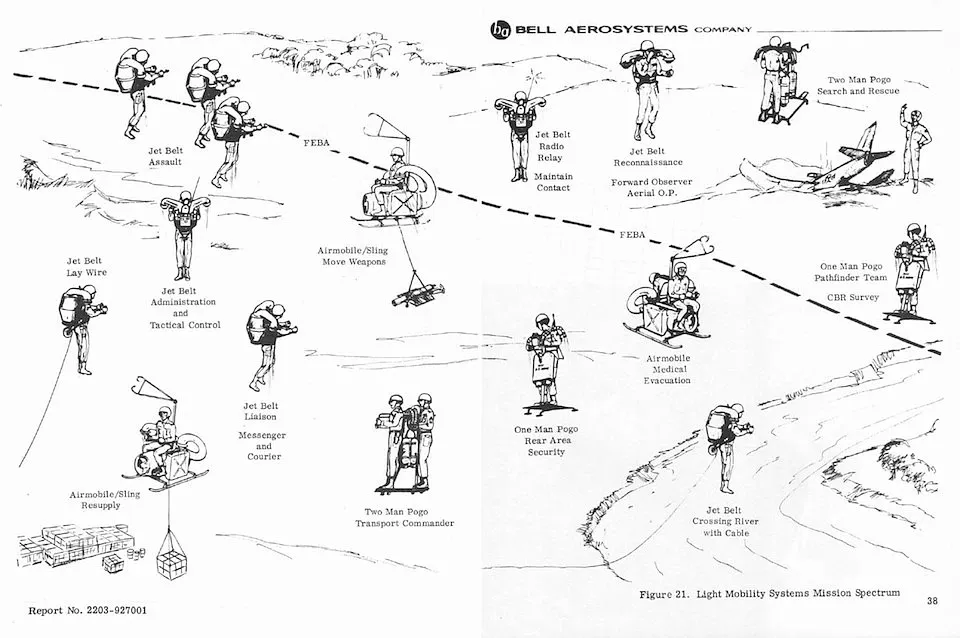

Zapata is pitching Fly-EZ as having broad military applicability, including supporting quick-reaction missions and routine patrols and helping personnel get quickly from a ship to shore or vice versa. With its high speed and minimal radar and infrared signatures, it might even offer a way to rapidly insert conventional or special operations forces into denied areas, its website explains. The company also says that the computer-controlled nature of the system might allow it to operate semi-autonomously as an unmanned aircraft.

But while the Fly-EZ is definitely an impressive piece of technology, it’s not clear whether it can truly overcome the long-standing issues with jetpacks and flying platforms. In the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. Army, in particular, spent considerable time and resources to evaluate a wide array of such systems, before ultimately deciding they were too impractical for a real battlefield.

Zapata’s latest creation is far faster and more reliable than these Cold War-era experiments, such as the Hiller VZ-1 Pawnee and the de Lackner HZ-1 Aerocycle. The Fly-EZ’s computerized controls are worlds ahead of those designs, though, making it far easier to train individuals with no prior flight experience to use them in the first place and keep going even in the event of an engine failure. These are significant advances in the overall concept of personal flying machines that substantially lowers the barrier to entry for adopting this technology for widespread use.

It still may not be enough to make Zapata’s offering practical, especially given its continued limitations in terms of range and overall flight duration. At 80 miles per hour, with 12 minutes worth of fuel, the Fly-EZ can over around 16 miles before it runs out of fuel. The 1950s HZ-1, early prototypes of which are seen in the first video below, had a range of up to 50 miles when carrying an additional fuel tank.

This might be enough time to cover the distance a typical “presence patrol” might travel around a base or small outpost, but hardly enough to provide the actual “presence.” It also wouldn’t offer enough range for troops to get ashore from ships without putting those vessels at risk from shore-based defenses during traditional amphibious operations, though it might offer a means for special operators to try and sneak on land from smaller boats.

Unless operators fly a loop from a base and back, they would have to carry extra jet fuel to fly it back out again, as well. The prospective unit cost of around $250,000 is around half that of small, purpose-built 4×4 light special operations vehicles, but it’s still unlikely that any U.S. military service would consider the Fly-EZ a disposable system. That price point also raises questions about how cost effective it would be to equip even small units with these individual flying platforms – just kitting out a single nine-man Army infantry squad would cost more than $2 million.

On top of all that, as with earlier designs, Fly-EZ continues to leave the operator entirely exposed to enemy fire and it’s not clear if the user can fire a weapon, even one-handed, while flying. Its speed, maneuverability, and altitude capabilities would help mitigate this vulnerability, but videos of the testing show that the platform is moving relatively slowly when it takes off or comes in to land. It’s loud, as well, largely ruling out covert insertions into denied areas or discreet operations at night.

That’s not to say that the system wouldn’t have any military or other practical uses. Depending on how well it packs up, it is possible that U.S. forces could drop them to downed pilots or other personnel who need to rapidly escape to safety. They could definitely offer a valuable way for personnel to respond to quickly to crises in and around established base areas, too.

Fly-EZs might offer a useful and cost-effective alternative to larger helicopters as a means of redeploying forces from one forward base to another with minimal support. It’s possible that they could offer a similar capability for employees other U.S. government agencies, such as the U.S. State Department, to safely and quickly travel between facilities overseas. Fly-EZ could also have various uses in non-combat, disaster relief missions, allowing personnel to quickly get into difficult reach areas to assess damage and potentially rescue trapped individuals.

Unfortunately, there seem to still be serious challenges to making individual flying machines work as well in real life as they do in action flicks and video games. Still, whether or not the system ends up in military use, Zapata’s Fly-EZ looks set to come closer than ever before to making this capability a reality.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com