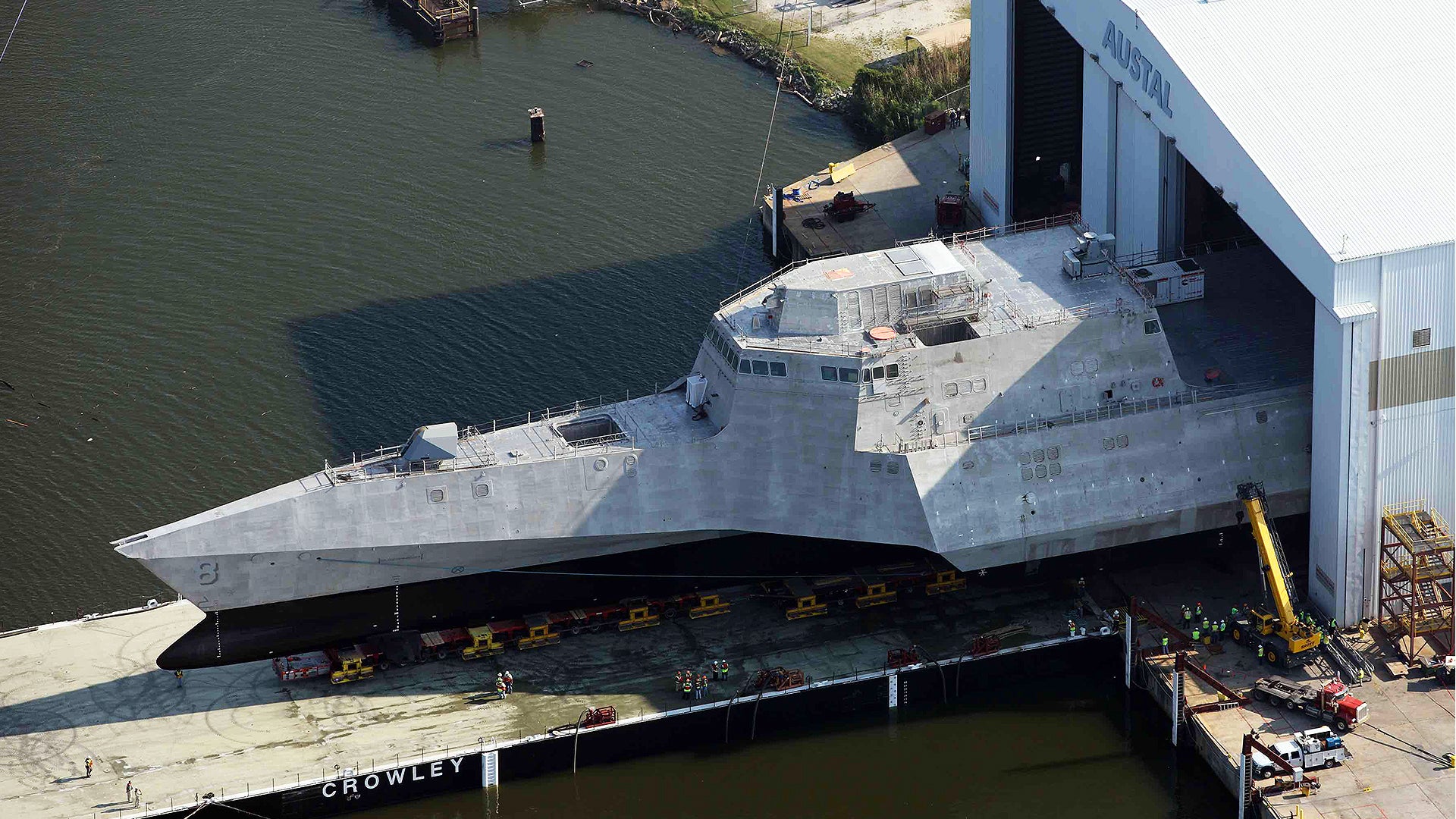

In yet another sign that expanded defense spending isn’t necessarily smart defense spending, your elected representatives on Capitol Hill just inserted three more Littoral Combat Ships into a committee markup of the 2019 defense budget. These are three ships the U.S. Navy does not want, pushing its truncated LCS buy from 32 of the unreliable and questionably effective ships to 35.

Your tax dollars at work folks!

Shipbuilding is really the most politicized facet of weapons procurement. It’s heavily infested with special interests and diseased with pork-barrel log-rolling. But regardless, it’s abundantly clear that the LCS is a loser. Even the Navy finally understands that money would be better spent on other platforms. The upcoming FFG(X) frigate, in particular, will be far more capable and adept at taking on the threats the country is slated to face in the coming decades than largely toothless, ill-conceived, and fragile half billion dollar jet boats.

Congress wants to order more LCS hulls regardless of this reality and that’s pretty much what they are getting as they have slashed funds for the already long-delayed mission modules that give LCS a purpose. And that purpose used to be multi-fold, with mission modules being switched out in a very short period of time in port, but that idea—the backbone of the LCS concept since it genesis—has since been tossed overboard. Now the ships will have a single mission module installed for the long term. In other words, what was supposed to be the example of multi-role flexibility and efficiency has become the exact opposite.

David Larter over at Defensenews.com broke the story and gives a great overview of the paradox Congress has created for the program:

“…When it comes to the mission modules destined to make each ship either a mine sweeper, submarine hunter or small surface combatant, that funding has been slashed.

Appropriators cut all funding in 2019 for the anti-submarine warfare package, a variable-depth sonar and a multifunction towed array system that the Navy was aiming to have declared operational next year, citing only that the funding was “ahead of need.” The National Defense Authorization Act had authorized about $7.4 million, still well below the $57.3 million requested by the Navy, citing delays in testing various components.

Appropriators are also poised to half the requested funding for the surface warfare package and cut nearly $25.25 million from the minesweeping package, which equates to about a 21 percent cut from the requested and authorized $124.1 million.

Nor are this year’s cuts the only time appropriators have gone after the mission modules. A review of appropriations bills dating back to fiscal 2015 shows that appropriators have cut funding for mission modules every single year, and in 2018 took big hacks out of each funding line associated with the modules.

The annual cutting spree has created a baffling cycle of inanity wherein Congress, unhappy with the development of the modules falling behind schedule, will cut funding and cause development to fall further behind schedule, according to a source familiar with the details of the impact of the cuts who spoke on background. All this while Congress continues to pump money into building ships without any of the mission packages having achieved what’s known as initial operating capability, meaning the equipment is ready to deploy in some capacity.

(The surface warfare version has IOC-ed some initial capabilities but is adding a Longbow Hellfire missile system that will be delayed with cuts, the source said.)

That means that with 15 of the currently funded 32 ships already delivered to the fleet, not one of them can deploy with a fully capable package of sensors for which the ship was built in the first place — a situation that doesn’t have a clear end state while the programs are caught in a sucking vortex of cuts and delays.

…

But the appropriators shouldn’t take all the heat, he added. The development of the different modules have hit technical issues and are all drastically behind schedule. The minesweeping package, for example, was initially supposed to deliver in 2008, but now isn’t slated to IOC until 2020, a date that will be further in doubt if Congress passes the appropriations bill as it left committee, sources agreed.

So we are buying more buns, but not the hotdogs to go inside them while everyone at the party wants pizza anyway. It is the epitome of waste. Oh, and let’s not forget that the Navy is still buying two brands of hotdogs and buns at two different markets across town just so that they can support their local grocers.

Food analogies aside, the Navy is betting all its chips on the LCS for one increasingly critical task—mine sweeping. Larter also makes note of this and the fact that the last Avenger class minesweeper will be put out of service in the early part of the coming decade. Larter writes:

The minesweeping package, for example, was initially supposed to deliver in 2008, but now isn’t slated to IOC until 2020, a date that will be further in doubt if Congress passes the appropriations bill as it left committee, sources agreed.

The Navy could very well find itself without any dedicated surface anti-mine warfare capabilities just as these nasty weapons are entering into a renaissance of sorts threat-wise. The delay in fielding the LCS’s minesweeping package has forced the Navy to ponder migrating some of its minesweeping capabilities to heavily armed but also already heavily tasked surface combatants. But in the past, similar initiatives haven’t worked well and bogging down multi-billion dollar assets to clear mines surely isn’t an attractive proposition to many in the seagoing service.

Other concepts are also being looked at to decentralize and distribute minesweeping capabilities. But actually doing so is more challenging than it sounds. Minesweeping is a risky art that requires expertise and training. It’s not an ideal task to be tagged on to already mission saturated sailors’ to do lists. Unmanned vehicles and other concepts can help streamline and automate the mission, but they too require specialized support.

But when you take a step back you realize that the whole thing would be silly if it weren’t so infuriating. The Navy could just replace its minesweepers with far less expensive and smaller vessels than Littoral Combat Ships—the Freedom class LCS is roughly three and a half times the displacement of an Avenger class minesweeper and far more complex. There are plenty of allied designs of ships this size that can be acquired off the shelf as well. And seeing as only eight of the LCS are currently slated to receive the minesweeping package, the raw number of ships dedicated to the task will shrink to an even smaller size than what the tired Avenger class represent today.

In the end, the LCS has created far more problems than it solves for the Navy, which some of us have been saying for many years while the Navy brass made laughably reaching statements about virtually all aspects of the program in order to keep it afloat. Now those chickens have come home to roost. And when it comes to a mission that has been largely neglected but no longer can be, like counter-mine warfare, the Navy would have been far better off just building a ship to do just that. Instead it is getting the same thing, just in a far larger and more expensive package.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com