Today, American supercarriers remain the largest and most expensive weapons on earth and are the ultimate symbol of power projection, but shortly following World War II they were just an idea. Then in 1949, that all changed when President Truman approved construction of USS United States (CVA-58), the first of four new supercarriers that would bring the strategic nuclear deterrence mission to the U.S. Navy’s fleet.

The initiative didn’t go as planned, but looking back, the United States class was incredibly novel and even forward thinking in some regards, and at the same time it was also incredibly nearsighted.

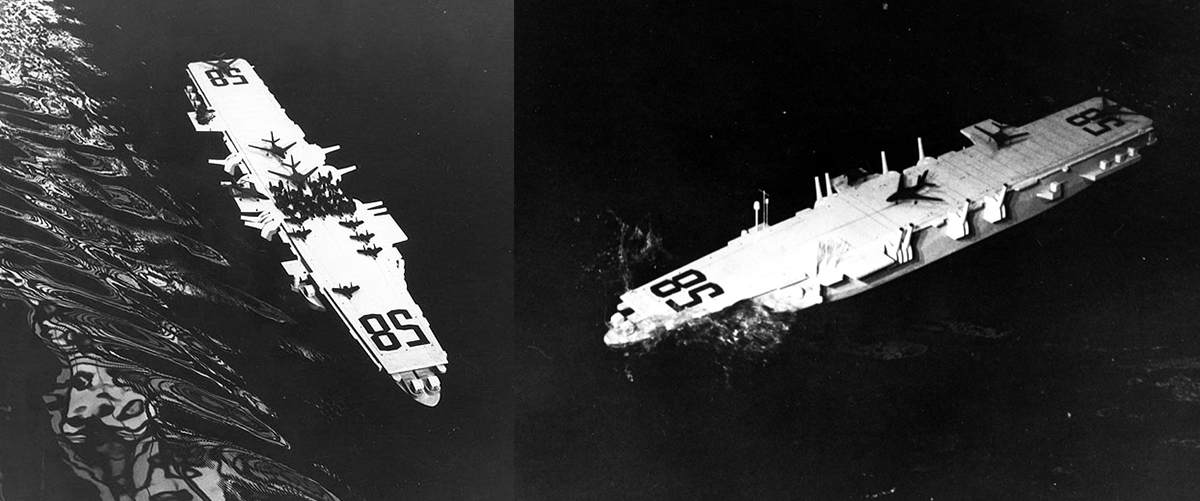

USS United States, the first carrier to be built in the post-World War II era, and her three sister ships were going to be supercarriers indeed. Measuring 1090 feet long and 190 feet wide, and displacing roughly 65,000 tons—83,000 tons when fully loaded—they would dwarf their predecessors. With eight Foster-Wheeler boilers and four Westinghouse turbines, USS United States would produce 280,000hp with her four screws propelling her to speeds in excess of 33 knots. The crew size would have been roughly 5,500 personnel, with nearly half that made up by the carrier’s embarked air wing.

Based on these metrics alone, USS United States as a link between earlier carrier designs and the Forrestal class of supercarriers that would emerge after the Korean War, is clear.

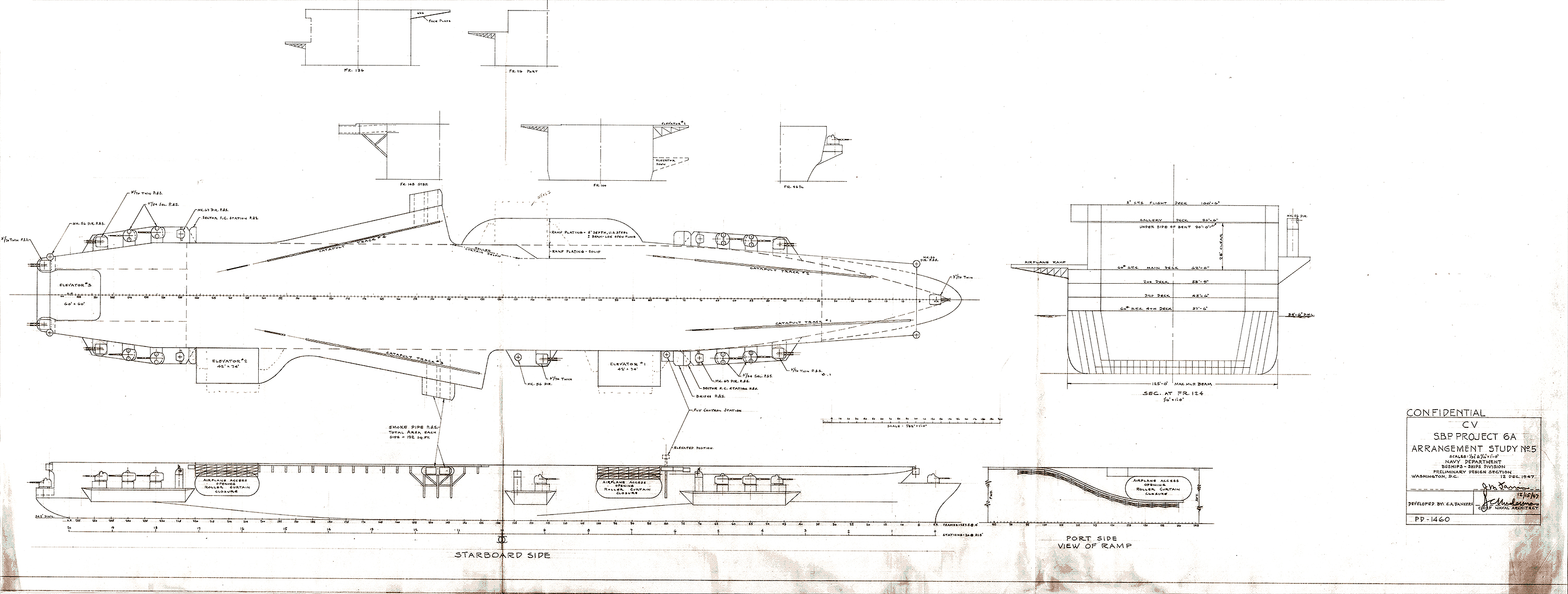

Other features were also foreshadowing the future of carrier design. CVA-58’s configuration rapidly evolved as the 1940s drew to a close. In its final form, the vessel’s four catapults were arrayed on the bow and angled out on the ship’s waist. The location of the ship’s four elevators, arrayed on the periphery of its deck to keep from interrupting flight operations and to keep from compromising the integrity of the heavily armored deck, looks somewhat familiar to what we see on supercarriers today.

But USS United States’ commonality with established supercarrier configuration ends there. The United States class was far more exotic. The whole concept focused on the ability to field bomber aircraft—each weighing upwards of 100,000lbs—at sea that would be capable of lugging the bulky and heavy nuclear weapons of the early atomic age over long distances to vaporize enemy targets.

With this requirement in mind, the ship needed to have an open enough deck to accommodate a jet bomber’s wide wingspan. As a result, there was no island superstructure. It was a flush-deck design that harkened back to the dawn of naval aviation. Even its funnels were retractable and arranged along the ship’s edge to provide the widest possible operating area for big nuclear-armed aircraft. There was no angled landing area either, although there were outcropped sponsons for launching fighters off the waist catapults while the main operating area was in use.

In addition, the ship’s deck would be heavily armored, instead of the hangar bay as in past designs. This resulted in a much higher center of gravity that was overcome by adding to the ship’s overall size and displacement.

Even getting the bombers into a hangar bay was less of a priority in the overall design as they were so large. Instead, most of them would live life in the elements on the ship’s deck throughout an entire cruise. A hangar bay did exist, but it was intended mainly to support a contingent of escort jet fighters that would also call the vessel home.

In all, the air wing would be made up of about a dozen bombers and 48 jet fighters, with a surge capacity to roughly 18 bombers and 54 fighters.

The lack of an island meant that the ship wouldn’t have a radar or any other command and control capabilities. A small pop-up wheelhouse was part of the design for basic navigation purposes alone, as well as an enclosed tower-like platform for directing movements around the deck. Beyond that, an accompanying specially outfitted command ship cruiser would have to provide all the ship’s radar, navigation, war planning, and command and control functionality. In a sense, USS United States the arsenal ship of her day.

As a ‘bomber carrier,’ nuclear strike was the ship’s primary mission, but it could also execute more traditional tasks like supporting amphibious operations, sea control, and tactical air support. They were planned to have been the centerpieces in a new 39 ship architecture that was tailored around them. Two smaller, more traditional carriers would operate alongside each of the four United States class supercarriers and her escorts to provide additional fighter escort and other duties, like anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare support. In all, the procurement of this force would cost at least $1.265B, with USS

United States costing $190M alone.

The whole concept was designed to challenge the USAF’s monopoly on nuclear weapons delivery. This enraged the newly minted Air Force’s top leadership, and the Army wasn’t too excited to see more funding and mission sets handed over to the Navy, either.

As the post World War II defense budget retracted, calls to outright cancel the United States class program grew louder. Then, on April 23rd, 1949 Defense Secretary Louis Johnson, who had just been on the job a number of weeks after President Truman fired Secretary of Defense James Forrestal who supported the Navy’s plans, canceled construction of the United States without seeking the approval of the Chief of Naval Operations. Navy Secretary John Sullivan resigned in protest.

Congressional hearings commenced to better understand Johnson’s snap decision. Through this process, the aircraft carrier’s modern utility in a nuclear age wasn’t well articulated and the decision to sink the United States class was upheld, with the USAF’s strategic bombers being favored over the Navy’s carriers for the nuclear delivery mission.

All this, as well as a number of other service rivalry and political factors, led to what is widely called the “Revolt of the Admirals,” where a number of the Navy’s top brass resigned in protest just as the CNO did. The shockwaves from this standoff between the services, Pentagon and White House leadership, still reverberate to this very day.

Even though USS United States was canceled, these events brought attention to the plight of the supercarrier in general and were intrinsic in seeing the far more conventionally configured and aptly named Forrestal class make it into production just half a decade later.

In the end, the Korean War proved that carrier air power was still highly relevant and a necessary investment—especially in conventional weapons terms. Nuclear weapons rapidly shrunk in size while increasing dramatically in power as well. By 1950, nukes were at sea about the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVA-42), a far smaller carrier than the USS

United States.

As for the Navy’s role in the Pentagon’s grander strategic deterrent mission, missile technology, and most notably the submarine-launched ballistic missiles, would make the outrage over canceling the USS United States a non-factor, and in retrospect, a glaringly good decision.

Still, while the Forrestal class gave birth to the supercarrier operationally speaking, the United States class was the genesis of the idea as a real fundable concept the Navy could hang its hat on.

Fast forward to today, an age of rapidly increasingly supercarrier prices, with the yet to be named fourth Ford class carrier costing $16B—almost the entire annual defense budget of Canada—and that’s just to purchase, not to operate for 50 years and then dispose of. Maybe the United States class concept could be mined for ideas on how to lower the cost and complexity of future carrier designs.

A shrunken island size and more deck area are already parts of the Ford class’s feature list, but the idea of deleting most of a carrier’s sensors, including their very costly radar system, and leveraging those on a nearby cruiser and from the strike group overall, is an interesting proposition. It is a far more plausible concept today, where advanced data-links and cooperative engagement capabilities are becoming common, than in the late 1940s when most all information was relayed by traditional radio communications.

Moving command and control, intelligence gathering and exploitation, and combat information center tasks to a surface combatant is also an interesting idea. Vessels like the Zumwalt class, which has a command deck more like the ones found at fixed installations on land that command entire wars than those commonly found on traditional surface combatants, may be able to accommodate such a concept. Even the Navy’s upcoming next-generation cruiser could be designed with this capability in mind.

Also the idea of placing larger, longer-range aircraft back on aircraft carriers is attractive considering the lack of range of modern naval tactical aircraft and the raising specter of anti-access/area-denial peer state conflict. In those scenarios, the threat posed by multiple anti-ship weapons technologies far outranges the reach of modern carrier-based combat aircraft.

The Navy is working to at least partially solve this problem with carrier-based tanker drones, but even then, aircraft with more generous unrefueled range would be highly prized assets for a modern American carrier air wing. Basically, this capability could be affordably fielded by procuring navalized unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs), which you can read all about here.

Even nuclear weapons may soon make their return to American carrier air wings in the weapons bays of F-35Cs. So in addition to looking at building smaller, conventionally fueled aircraft carriers to replace at least a portion of the Navy’s supercarrier force, maybe examining what a modern supercarrier arsenal ship type concept would look like and what it would cost would be a logical endeavor.

Regardless, that’s the tale of the abortive United States class, the first American supercarrier that almost was.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com