A group of independent Turkish lawyers has petitioned the country’s courts to arrest nearly a dozen U.S. military personnel over alleged links to a coup attempt against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2016 and a leaked document purports to show that they were directly involved in planning the plot. These latest accusations again call into question whether it still makes sense for the U.S. government to store dozens of nuclear weapons at Incirlik Air Base in the country or even use that facility as a springboard for conventional military operations.

The Turkish legal non-governmental organization Association for Social Justice and Aid, which includes prominent backers of Erdoğan’s government and enjoys support from the country’s authorities, filed the charges with the Adana Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office on Aug. 3, 2018. The 60-page criminal complaint also calls for Turkish officials to shut down U.S. military flights from Incirlik, a portion of which the U.S. Air Force has sole control over, and execute a search warrant at the facility to look for additional evidence. So far, the Turkish government does not appear to have acted on any of the charges.

The charges claimed the Americans were “attempting to destroy the constitutional order [of Turkey], attempting to prevent partially or totally the Turkish government from exercising its authority and endangering the sovereignty of the Turkish state,” according to a translation by the Stockholm Center for Freedom, a group Turkish journalists operating in self-imposed exile in Sweden. As such, authorities needed to “arrest the commanders of the U.S Air Force who are the superiors of the soldiers based at Incirlik and took a role in the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016.”

The complaint specifically calls for the arrest of 11 individuals, but it’s not clear if any of them are still assigned to Incirlik. The first two are U.S. Air Force Colonels John Walker and Michael Manion, who were, respectively, the commander and vice commander of the 39th Air Base Wing at Incirlik in 2016.

It does look like they might have originally intended to seek the arrest of American personnel at the base now, though. U.S. Air Force Colonel David Eaglen was commander of the 39th Air Base Wing until July 10, 2018. But other current and former members of the U.S. military that the Association for Social Justice and Aid wants the Turkish government to detain were never there.

These include the present U.S. Central Command chief U.S. Army General Joseph Votel and Director of Regional Affairs for the Deputy Under Secretary of the Air Force U.S. Air Force Brigadier General Rick Boutwell. Now retired U.S. Army General John Campbell, who was last in charge of the NATO-led coalition in Afghanistan, is named in the group’s complaint, too.

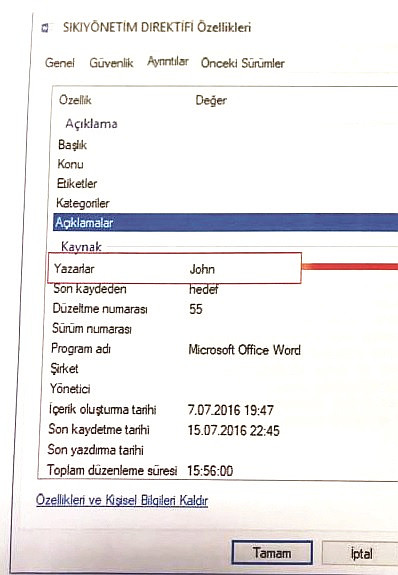

On Aug. 7, 2018, the Turkish newspaper Yeni Şafak, which also has strong ties to the president and routinely voices its support for his administration, then released images it says are of a memorandum detailing plans for martial law during the abortive coup with metadata that showed the author’s name was “John.” Turkish officials reportedly found the document while searching through Emails belonging to Hüseyin Ömür, who served as an aide to General Mehmet Partigöç, a military officer implicated in the plot to boot Erdoğan from office.

According to the report, Turkish officials are now claiming they plan to investigate anyone named John who was in Turkey at the time. The clear suggestion, however, is that this individual could be Colonel Walker or former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey John Bass, though Yeni Şafak offered no additional evidence to substantiate those claims.

Yeni Şafak has also accused retired U.S. Army General Campbell of having a hand in the coup attempt, without evidence, in the past. There have also been previous allegations that Ambassador Bass might have a connection to the incident and Incirlik has been at the center of various conspiracy theories given that the Turkish Air Force, which operates its own facilities at the base, was heavily involved in the plot to overthrow Erdoğan.

But tensions between the United States and Turkey have been steadily rising since the coup attempt occurred in general. Erdoğan and his supporters insist that Fethullah Gülen, an Islamic cleric and former political ally of the president who now lives in self-imposed exile in the United States, was the mastermind of the plot. Gülen has been an outspoken critic of Erdoğan’s steadily more dictatorial policies.

Turkish authorities have yet to present the necessary evidence to their American counterparts to support an extradition request. Instead, they have reportedly sought alternative means of detaining Gülen, including a reported kidnapping plot involving former National Security Advisor to U.S. President Donald Trump and retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Michael Flynn.

More recently, Erdoğan has sought to use an American evangelical Christian minister, Andrew Brunson, as a bargaining chip. Brunson got swept up in a wave of arrests following the coup attempt and stands accused of terrorism and seeking to undermine the state, charges his lawyers say are unsubstantiated and purely political.

The legal action from the Association for Social Justice and Aid and Yeni Şafak’s document leak both came soon after the Trump Administration sanctioned Turkey’s Justice Minister Abdülhamit Gül and Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu over a failure to fully free Brunson from pre-trial detention. In July 2018, Turkish authorities released Brunson from prison, where he had been for more than 20 months, but then put him under house arrest instead.

Since April 2018, Brunson’s detention has become increasingly wrapped up in a separate U.S.-Turkey spat over the latter country’s decision to purchase S-400 surface-to-air missiles from Russia. There are concerns that those the presence of those systems, and the Russian specialists necessary to training Turkish personnel how to use them, could compromise secrets related to the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, an issue you can read about in more depth here and here.

U.S. lawmakers have now moved to block the delivery of the jets, and/or support services essential to their operation, unless the Trump Administration can assure them that any risks are sufficiently mitigated and that Brunson is receiving fair treatment. Turkey, not surprisingly, has been highly critical of these moves.

American and Turkish authorities have already sparred over the matter of U.S. military support to Kurdish groups in neighboring Syria that Turkey says are linked to domestic terrorists. The United States has expressed its own reservations about its fellow NATO member’s strengthening ties with Russia in the region and more broadly, as well.

These complicated and intertwined issues all come together against the backdrop of the fact that the U.S. military continues to rely heavily on Incirlik and other sites in Turkey to support its operations in Syria, as well as broader regional security plans. For example, the U.S. Army operates a powerful AN/TPY-2 radar at a separate Turkish facility as part of the United States’ ballistic missile defense shield.

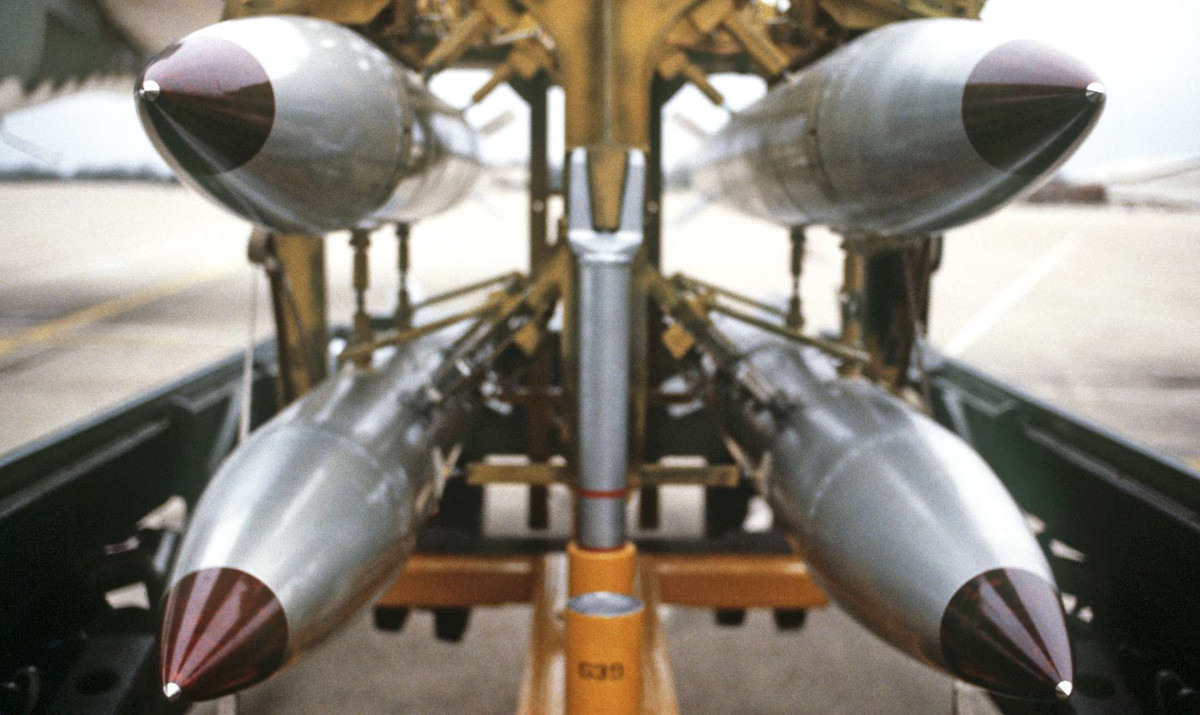

By far, the biggest concern is what impact worsening U.S.-Turkish relations might have on the dozens of B61 nuclear bombs that the U.S. Air Force stores at Incirlik. The United States has nuclear weapon sharing agreements with four other NATO members – Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands – but the bombs in Turkey would be for its use only during a major crisis.

Since the coup attempt, we at The War Zone, among others, have called the safety and viability of this plan into question. The latest legal challenge against personnel who worked at Incirlik and the insinuation that Americans at the base and elsewhere were involved in the coup attempt can only further weaken the level of trust between the U.S. military and its ostensible Turkish allies, no matter what American officials might say.

In addition, this could only cause both sides to question whether the other is a viable partner in any future conflict, let alone a nuclear one. Turkey has already limited the U.S. military’s ability to use the base for conventional operations, directly or indirectly, due to conflicting political agendas more than once in the past.

The willingness of Turkish authorities to impose restrictions and of private, but politically connected individuals to accuse American personnel of complicity in crimes without any clear evidence only further raises the question of whether Incirlik serves as a reliable strategic lilypad at all. As of March 2018, the United States had already reduced its use of the facility for combat operations in Syria and was reportedly seeking to make some of those reductions permanent. It’s not clear if those plans extended to other sites in the country.

And though the U.S. military is working to reduce tensions with Turkish forces and their partners in Syria, it’s hard to see the Pentagon reversing this course any time soon, given the current political situation. A delegation from Turkey touched down in Washington, D.C. on Aug. 8, 2018, for talks aimed at resolving the issues surrounding Brunson and the sanctions against Justice Minister Gül and Interior Minister Soylu, as well as the general strains between the two NATO members.

It’s far too soon to tell whether this diplomatic engagement will actually produce results. That’s not to say things couldn’t change if Erdoğan were to soften various positions and reverse his most authoritarian policies, but the Turkish president has been consistently defiant and has little apparent interest in acquiescing to the various American demands without significant concessions.

And with all this in mind, the question remains about how long the United States can reasonably hope to keep its B61s stored away at Incirlik. It would seem the situation is becoming increasingly untenable overall.

If Turkish authorities were to pursue the complaint from the Association for Social Justice and Aid and if that led to the detention of American military personnel at Incirlik, it could undermine any diplomacy between the two countries in the near term and have even more negative consequences in the long-term. Any actual arrests, in particular, would set a precedent that could leave members of the U.S. Air Force, or individuals from any other branch of the American military serving in Turkey, at risk of becoming political prisoners.

If nothing else, this would sap morale and breed more distrust between U.S. personnel and their Turkish counterparts. It’s also just an unreasonable situation for American servicemen and women to find themselves in while deployed to facilities on the territory of a treaty ally.

All of this would seem to be pushing the United States toward gutting its presence at Incirlik, at least for the time being, even if only to protect American personnel from politically motivated harassment. But doing so could lead to broader changes in how the U.S. military operates in Turkey and perhaps provide the prompt to finally remove its nuclear weapons from the country.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com