A new report from the Government Accountability Office, or GAO, says that it could cost the Navy more than $1.5 billion to fully dispose of the retired ex-USS Enterprise, a complete process that could take more than 15 years to finish. The watchdog says the service should get at least one independent review of those projected costs and begin keeping studious records, not only to make sure it’s getting the best deal, but to also learn as much as possible from this unprecedented ship breaking effort for when it retires its Nimitz class supercarriers.

The Navy officially decommissioned Enterprise, also known by its hull number CVN-65, in February 2017, after more than five decades of service. The ship had already effectively been in mothballs since 2012 and Newport News Shipbuilding completed a lengthy “inactivation” process, which included removing nuclear fuel, mission systems, and other items from the ship, in April 2018.

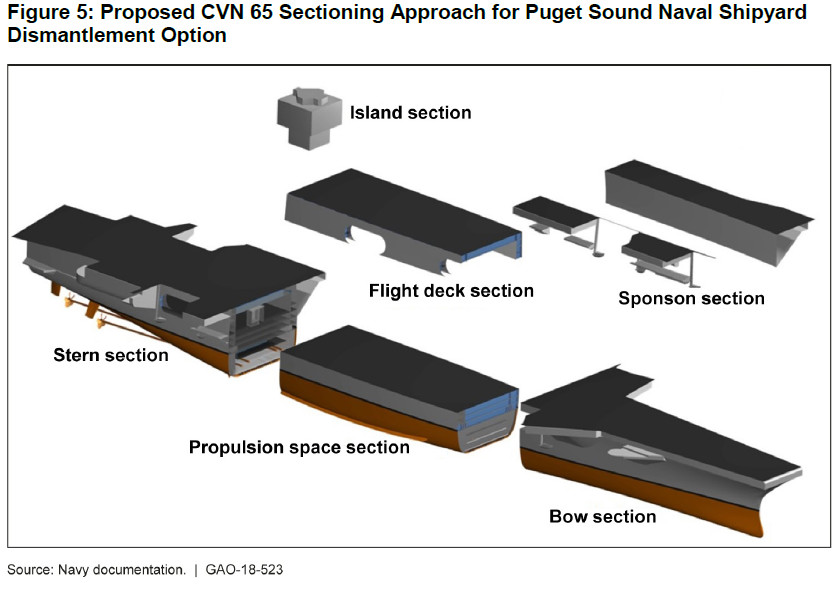

“At approximately 76,000 tons, CVN-65 will require an unprecedented level of work to dismantle and dispose of as compared to previous ships,” GAO’s review, which the congressional office published publicly on Aug. 2, 2018, said. “Regardless of the approach the Navy chooses, CVN-65 will set precedents for the processes, costs, and oversight that may be used to dismantle and dispose of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers in the future, such as the Nimitz-class carriers which the Navy will begin to retire in the mid-2020s.”

The only ship of her class, Enterprise was also the first ever nuclear-powered aircraft carrier to enter service anywhere in the world. The Navy expects to send the USS Nimitz, the first ship in the class that came after CVN 65, into retirement in 2023, after sometime after the future Ford-class flattop USS John F. Kennedy enters service. There is already considerable debate over this plan, though, and Congress may block the retirement in order to maintain a 12-carrier fleet.

How to dispose of the “Big E,” as she was nicknamed, has already been a complicated and arduous affair. The Navy originally projected that it would cost somewhere between $500 and $750 million to scrap it, but by 2013, this figure had grown to over $1 billion. The difficulties have forced the service to push back the start of the process more than once already and the ship’s hulk is presently sitting in Hampton Roads, Virginia.

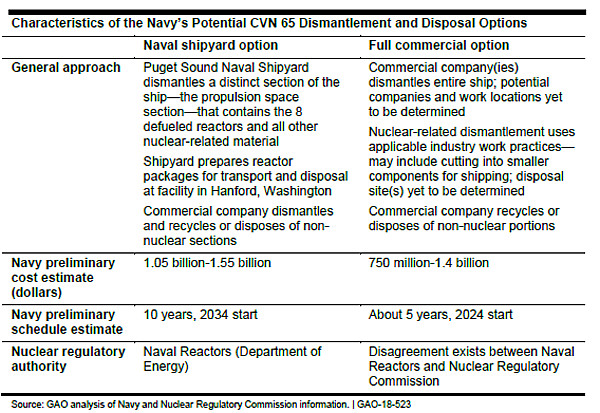

The Navy is now considering two potential options, according to GAO. The first of these is doing the work at a naval shipyard with the help of contractors, while the second would see the service turn the ship over to a private company to break down at their own facility.

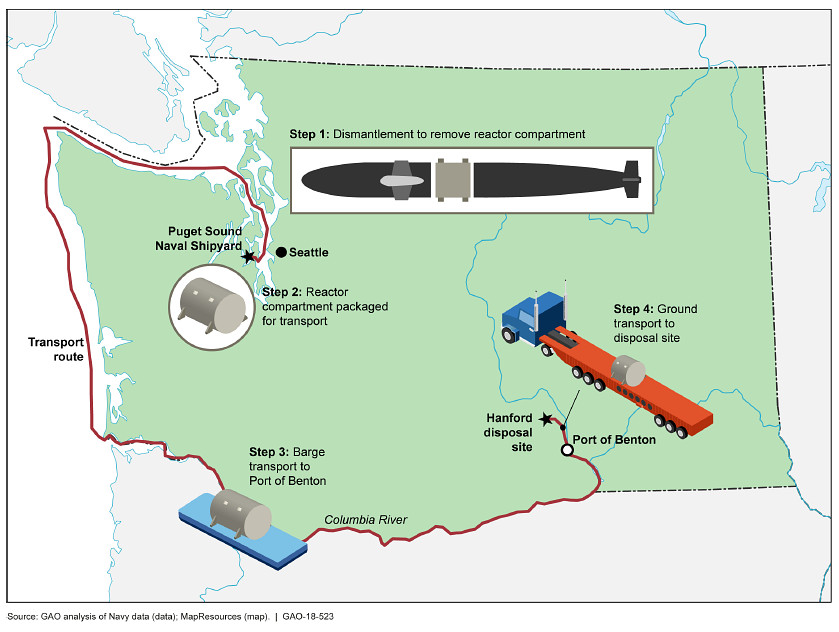

Historically, the Navy has done this work at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Bremerton, Washington. When it comes to breaking down nuclear-powered vessels, this facility has the added benefit of being relatively close to the Department of Energy’s Hanford low-level radioactive waste disposal site, which is also in Washington State. This is where the Navy would send the eight de-fueled nuclear reactors and related components from the ex-Enterprise.

GAO acknowledged in its review that the Navy had a better sense of the costs and time required to proceed with this plan based on its existing experience. Unfortunately, there are serious concerns that using one of the service’s own overworked shipyards to scrap the supercarrier would only add to an increasingly troubling maintenance backlog for active ships and submarines.

In September 2017, the watchdog released a separate review highlighting the poor and decaying state of the Navy’s shipyards. The next month is published yet another report specifically on delays in maintenance availabilities for Los Angeles– and Virginia-class attack submarines. At the time of writing, the Los Angeles-class boat USS Boise is still just sitting idle pier side after more than 30 months of inactivity.

The Navy only expects the repairs on Boise to begin

in 2019. On Aug. 2, 2018, the service put out a request for information to try and identify commercial shipyards that it could certify for government work or ones that already have that certification, but are not working at full capacity, in order to try and make up for some of these shortfalls.

The fear is these shipyard capacity issues could also lead to greater costs if the process drags out. The Navy says the Puget Sound option could cost anywhere from $1.05 to $1.55 billion, take 10 years to complete, and wouldn’t even start until 2034.

The other option, then, is to have a contractor, such as Newport News, do the job at one of their facilities. This could shorten the time it takes to break down the former Enterprise to only five years and get the work going in 2024.

The issue here is that no government or private shipyard has ever done anything like this on this scale. It could quickly become expensive as contractors begin ripping things apart and find out that their expectations don’t line up with what they’ve discovered waiting for them – something that’s happened before with much smaller, less complicated systems, such as fighter jets.

The unique nature of Enterprise‘s design could make things even more complex. More than two decades after the Navy struck it from the rolls, the bulk of the hull, including the reactor compartments, of the ex-USS Long Beach, another one-off design and the first-ever nuclear-powered cruiser in the world, is still sitting in long-term storage at the Washington State base.

And though the Navy has moved reactors and other irradiated materials from Puget Sound to Hanford in the past, the sheer volume of materials associated with eight individual reactor plants will make this effort more akin to decommissioning a nuclear power plant. For a commercial contractor, getting legal and regulatory approval to dismantle the reactors, in particular, could be complicated and limit the available sites where the work could occur.

The Navy and the independent Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) already disagree on what standards should apply to the commercial option. The Navy says that if a commercial company does the work, NRC’s should view it through the lens of commercial nuclear regulations. The NRC says that dismantling a naval nuclear reactor is akin to disposing of a nuclear weapon from a regulatory standpoint and that the Navy needs to be responsible for the process and disposing of the waste at a site such as Hanford.

Furthermore, NRC only has direct authority over such matters in thirteen states, not including Virginia, where the ex-Enterprise is now. State authorities have entered into agreements with the commission in all other instances to take responsibility for nuclear waste and other related matters and might not be willing to take on the task of overseeing the disposal of eight military-grade reactors. And not mentioned at all is the highly classified nature of U.S. naval nuclear reactor design, the details of which any company would have to guard very closely throughout the process regardless.

So, while there might be an understanding of the general approach a commercial company would take to break up the ex-Enterprise, there’s no real understanding of what the process might entail, especially with regards to the nuclear components. For example, GAO said in its report that the Navy, for unknown reasons, estimated that it would cost less to dispose of each of the ship’s nuclear reactors than it typically does to get rid of commercial reactors of a similar size. With so many unknowns, the estimated final cost for the commercial option is a wide range that sits anywhere from $750 million to $1.4 billion.

“As the Navy considers how to proceed, it will be critical to ensure that there is sufficient oversight and accountability for what likely will be an effort greater than $1 billion that lasts the better part of a decade,” GAO’s reviews wrote in their conclusion. “Without establishing a cost and schedule baseline that has been validated by an independent cost estimate or assessment, it will be difficult for decision makers to track cost and schedule performance or have confidence in CVN 65 costs.”

As such, the watchdog recommended that the Navy have the Pentagon’s Office of Cost Analysis and Program Evaluation or the Naval Center for Cost Analysis draw up independent cost analyses of the two potential courses of action. They also said the service should keep and supply details accounting of the projected costs and the money it spends on the project, which it is not presently required to do for disposal programs.

In addition, GAO said that the Secretary of Defense needs to demand that the Navy craft a risk management plan no matter what course of action it takes and goes through a formal process to establish a baseline cost and schedule for the entire effort. Without this it would be difficult, if not impossible, to truly evaluate how things go, which could hamper the service’s ability to avoid the same mistakes in the future. The Department of Defense told the congressional office that it agreed with all of these suggestions.

It’s also worth noting that how the disposal of Enterprise shakes out could have an impact on how the U.S. government views the costs associated with nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and could impact the growing debate about whether it makes sense to invest in smaller, conventionally-powered types. Since taxpayers will be responsible for the bill, a more accurate estimated lifecycle cost of a nuclear supercarrier should include this $1 billion or more to dispose of it at the end of the day.

As it stands now, the Navy hopes to have arrived at a final decision on what to do with the remnants of the Enterprise by 2023. We might not have to wait long to start seeing hints of which course of action the service truly prefers.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com