U.S. lawmakers from the House and Senate have agreed on a final version of the approximately $716 billion defense spending bill for the 2019 fiscal year, which requires the U.S. military begin work on developing new warning satellites to spot incoming ballistic missiles and weapons to blow them up from space. The draft law requires the Missile Defense Agency to pursue these programs even if it argues against them in an up-coming ballistic missile defense strategy review, which might be setting the Pentagon up for a battle with Congress, but might also highlight the opinions of certain senior U.S. military leaders.

Legislators announced they had agreed on a single version of the law, formally known as the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, on July 23, 2018. The House expects to put the measure to a vote by the end of the month and then send it to the Senate in August 2018. If it passes both chambers, then it would go to President Donald Trump to become law.

Near the end of Subtitle E, the portion of the bill that covers dedicated missile defense efforts, are two separate sections, 1660C and 1660D. Their language is relatively sparse since they only serve to modify two portions of the previous National Defense Authorization Act for the 2018 fiscal cycle.

The impact of these changes, however, is anything but minor. In both cases, the draft law removes the following phrase “If consistent with the direction or recommendations of the Ballistic Missile Defense Review that commenced in 2017” from the existing law.

The video below provides an overview of the U.S. military’s existing ballistic missile defense shield.

This means the Pentagon is no longer allowed to wait until that report is ready to decide whether or not to begin working on putting sensors and weapons in space to defend against ballistic missile threats. In addition, the wording in the draft bill would prevent the Missile Defense Agency, which will be in charge of these projects, from halting this work even if the review recommends abandoning the space-based systems.

Legislators look set to establish a fixed and aggressive schedule for these developments, as well. The sensors need to be deployed no later than the end of 2022, according to another change to the existing sections.

Based on the existing language in the defense spending bill for the 2018 fiscal year, the lawmakers want to the Missile Defense Agency to come up with a plan to finish development of the space-based weapons to destroy incoming missiles within a decade and potentially start testing a prototype system in 2022, which would be when the sensors are supposed to go online.

The space-based weapons will be “regionally focused.” That is to say, it will be positioned to respond to threats from only one specific part of the world, such as the area around Iran or North Korea.

They will also be configured to destroy hostile missiles during their vulnerable boost phase right at the beginning of their flight. It’s worth noting that the U.S. military is already pursuing aerial boost phase intercept concepts, using either solid-state lasers mounted on high-flying drones and a physical kinetic weapon, as well. The goal for the space-based system is to achieve “an operational capability at the earliest practicable date,” according to the defense budget law for fiscal year 2018.

Beyond offering an additional layer of defense, any boost phase intercept system also provides an additional deterrent quality, since it threatens to drop portions of the missile right back down on the country that launched it. Depending on the missile’s payload, this could include radioactive material from a nuclear warhead or chemical or biological agents.

Even though we don’t know what the conclusions of the up-coming Ballistic Missile Defense Review might be, it seems easy to see how this language could put the U.S. military in a bind. Lawmakers are essentially telling it to disregard its own expert advice on space-based systems, no matter what it is. Even if the final report recommends pursuing some combination of sensors and weapons, the Missile Defense Agency won’t be able to act on those suggestions rather than following Congress’ direction. At most, it could try to follow both sets of guidance simultaneously.

The change in the language reflects the clearly growing anxiety among legislators about the potential for ballistic missile attacks against the United States from various countries, especially North Korea. There was a flurry of North Korean developments in 2017, especially the debut of the Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile, which could potentially carry a nuclear warhead to the continental United States. This helped in no small way to push lawmakers to increase spending on ballistic missile defense that year and include the provisions for additional systems, such as the space-based systems, in the fiscal year 2018 defense budget bill in the first place.

There’s a lot of evidence to suggest Congress and the Pentagon may actually be thinking along similar lines when it comes to missile defense in space. The two sides were in alignment on the growing importance of the ballistic missile defense shield in 2017, even if the Pentagon was reticent to divert additional resources to it from existing priorities, at least initially. This attitude has steadily changed.

“There are not enough ships, there are not enough islands in the Pacific that radars can answer all of your sensor questions,” U.S. Air Force General John Hyten, in charge of U.S. Strategic Command, explained to reporters at a missile defense-related event the Association of the U.S. Army hosted in February 2018. “[The U.S. military is] going to have to go to space.”

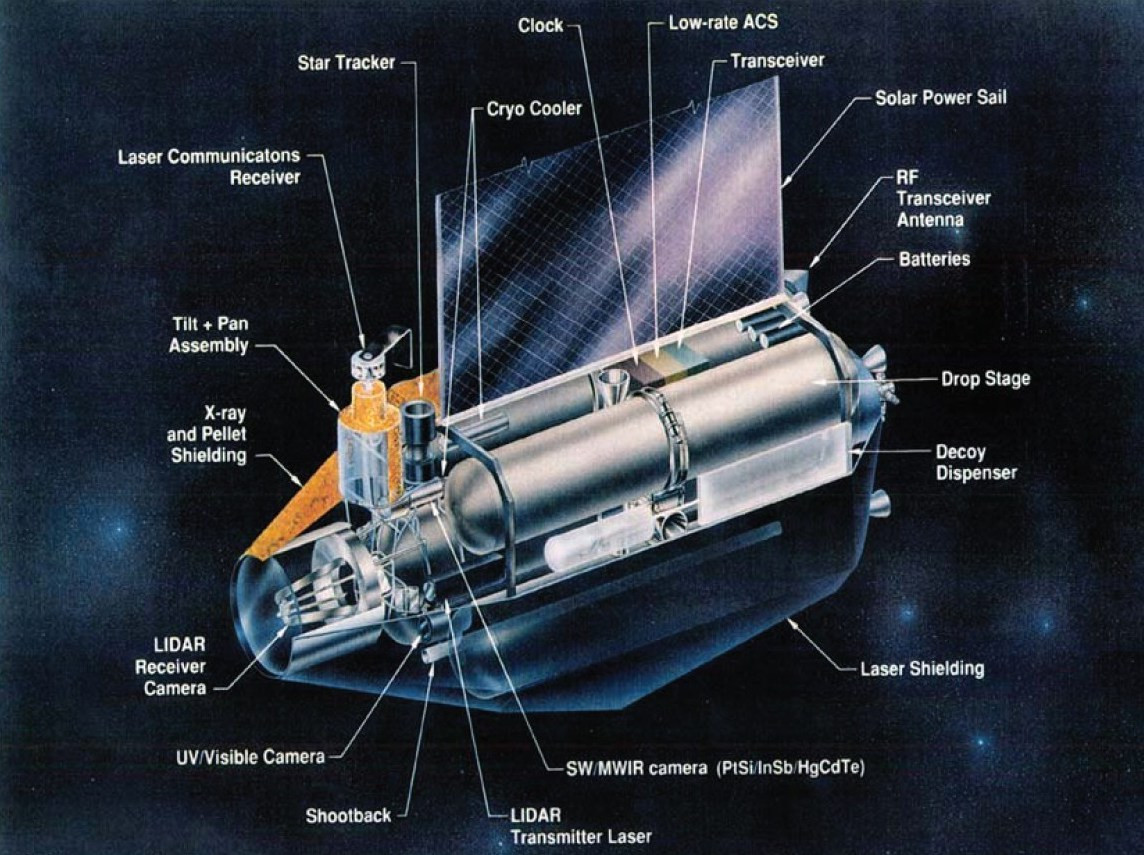

Hyten spoke specifically about the need to speed up development and fielding of the Midcourse Tracking Sensor, which will be able to track threats in the cold vacuum of space. At present, U.S. military surface- and space-based sensors primarily spot and track missiles during launch and again when the warheads they carry begin to come down at the other end of their flight trajectory.

One of the existing sensors, the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS), may have some limited “cold body tracking” functionality, but not to the desired level. Really, the biggest limiting factors are the logistics and costs associated with deploying enough radars, which can have a relatively narrow field of view, and satellites to provide persistent coverage.

Without a more robust capability, though, there is an ever more dangerous gap in the stream of information where traditional ballistic missiles have a perfect opportunity to deploy decoys or other countermeasures to throw off defenders. The existing combination of systems also has no effective means of monitoring the travel of hypersonic vehicles while they are briefly in space or as they careen through the upper atmosphere. You can read about these issues and the Midcourse Tracking Sensor in more detail here.

At the same time, this clear need to have advanced anti-ballistic missile sensors in space, and improving U.S. military capabilities in space broadly, has revived discussions about putting actual weapons of some sort up there, too. In March 2018, Michael Griffin, the present Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, highlighted various possible weapons that could be well suited for space-based missile defense applications, especially various types of directed energy weapons, at the 2018 Directed Energy Summit, which private firm Booz Allen Hamilton hosted.

“I’m going to be very welcoming of other approaches that may not have had a lot of focus in recent years or recent decades,” Griffin said. “I would urge us to keep a lot of arrows in our quiver as we go forward figuring out how we’re going to translate directed energy technologies into warfighting systems that are going to defend this country and our allies.”

Still, even if space-based defenses supporters in Congress and Pentagon find themselves in agreement, it is unlikely that there will be unanimous support for these projects throughout the legislature or the public at large. Ballistic missile defenses are already a controversial and often misunderstood topic, as we at The War Zone have previously examined in detail.

Space-based weapons, whether they are advanced directed energy weapons or physical interceptors, have historically proven to be complex, expensive, and unreliable. Griffin probably knows this as well as anyone, having been a member of President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative.

This program became derisively known as “Star Wars” and was associated with a host of technologies experts decried at the time as impractical, exorbitantly expensive, or both. The interception portion included space-based lasers, particle beams, railguns, and finally, an elaborate orbital weapon system known as “Brilliant Pebbles.”

This final concept involved relatively small satellite-based kinetic interceptors that would be scattered throughout orbital space and activated as necessary. By 1990, the plan was to build 4,600 individual interceptors at a total cost of $55 billion – equal to more than $95 billion today.

This didn’t include the funds necessary to support the “Brilliant Eyes” sensors that would have supported the complete system. In 1993, President Bill Clinton canceled the program and renamed the Strategic Defense Initiative as the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, the predecessor to today’s Missile Defense Agency.

A quarter of a century later, the U.S. military seems to be ready to give this another shot and Congress seems eager to push it along. Technology has advanced considerably since the U.S. government scrapped Brilliant Pebbles, including with regards to solid-state lasers, high-power microwaves, and railguns.

Regardless, it’s still unclear if there are any systems, and the sensors necessary to cue them in space, that have reached a place where space-based missile defense is feasible at a price that is practical. There’s also the question about whether the United States could deploy them, even with a limited regional focus, at a cost that doesn’t threaten to eat away at other defense spending priorities. It will be hard to get ever around the reality that it is and is likely to remain cheaper and simpler for any potential opponent to just build more missiles than it is to devise ways to intercept them.

There will almost certainly be concerns about the militarization of space broadly, as well, especially since many of the weapons in question could potentially engage other types of targets beyond ballistic missiles. At present, the Outer Space Treaty bans signatories, including the United States, from placing nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in orbit, but has no such stipulations about conventional systems. The U.S. government has blocked subsequent efforts at the United Nations to fully outlaw the deployment of any space-based weapon.

“There is a lot of [skepticism] about the technical feasibility and the cost, and those are valid concerns, those aren’t unrealistic concerns. We should always be worried about that,” General Hyten said in said in February 2018 at the Association of the U.S. Army event. “It has caused the department to continue to look at it and say: ’We are not quite ready, we need to study it a little more.’ But I think we are ready now.”

With the language in the latest draft defense spending bill, Congress seems determined to find out as soon as possible.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com