As the U.S. Air Force continues to stumble through its latest attempt to procure a light attack aircraft, it is important to remember just how often the U.S. military as a whole has waffled, dithered, and squabbled over the concept in the past. The U.S. Army’s OV-1 Mohawk, which did have a lengthy career as a surveillance aircraft, is one of the earliest examples of competing priorities and infighting between services killing plans for what could have also been an effective light attack platform.

By the time the Grumman-made aircraft, also known as the G-134, first flew in 1959, the Mohawk program had already been something of a saga for nearly three years. Originally the Army had teamed up with the U.S. Marine Corps to work on a plane to replace the small Cessna O-1 Bird Dog observation plane that both services were still flying at the time.

“The requirement was for an aircraft capable of rough field operation with short take-off performance and equipped for tactical observation and battlefield surveillance missions,” according to an official Army historical monograph the service published in 1991. “The Marines withdrew from the project before the first flight, leaving the Army to continue development alone.”

But the Army and the Marines had both relied on the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics to do the contracting. So, as it happened, the Army received its first nine prototype Mohawks via a Navy-run deal in 1959.

The Mohawk has a unique and instantly recognizable shape with a distinctive triple tail – the original design actually had a T-shaped tail – turboprop engines mounted over its wings, and bug-eyed cockpit. The latter design element provided the crew of two with excellent visibility to spot targets of interest on the ground.

By the end of 1959, the Army had ordered more than 70 Mohawks in three variants and assigned them each designations in its own short-lived aircraft nomenclature system. The bulk of these were AO-1AFs was a visual surveillance type with a KA-30 film camera in the fuselage that the crew could point to the left or the right of the aircraft as desired. Pods with upward ejecting flares would provide illumination for night photography.

The AO-1BF carried a then state-of-the-art AN/APS-94 side-looking airborne radar (SLAR), a radar imaging sensor, in a long pod under the right side of the forward fuselage. The AO-1CF was virtually identical to the AF version, but carried an AN/UAS-4 infrared line-scanning camera. Both of these variants could collect imagery day and night without the need for flares. In 1962, under the new tri-service designation system, the AO-1AF, BF, and CF became the OV-1A, B, and C, respectively.

The Mohawks were a key component of the Army’s then relatively novel “airmobile” concept, which envisioned troops employing both helicopters and light fixed-wing transports to rapidly deploy into certain areas to perform tasks such as establishing a “beachhead” of sorts for follow-on forces or quickly encircling opponents. The aircraft actually used the same Lycoming T53 turboprop engine as the then relatively new Bell Huey helicopter, which would have helped simplify maintenance requirements in the field.

Since the airmobile doctrine inherently expected those troops to operate for an extended period of time without necessarily being able to rely on support from other Army units or forces from other services, the potential value of arming at least some of the Mohawks quickly became apparent. The service even experimented with using its new AC-1 Caribou light transports – later known as CV-2s and then C-7s – as small mid-air refueling tankers to help extend the range and loiter time of the OV-1s for both reconnaissance and light attack missions.

The fledgling Special Forces community, which also expected to operate behind enemy lines for extended periods detached from conventional support, was also immediately interested in the Mohawk as a light attack aircraft. This was part of a larger plan called Light Aviation Special Support Operations, or LASSO, which shouldn’t be confused with U.S. Special Operations Command’s present-day Light Attack Support for Special Operations program, also abbreviated as LASSO, though it might help explain the choice of name.

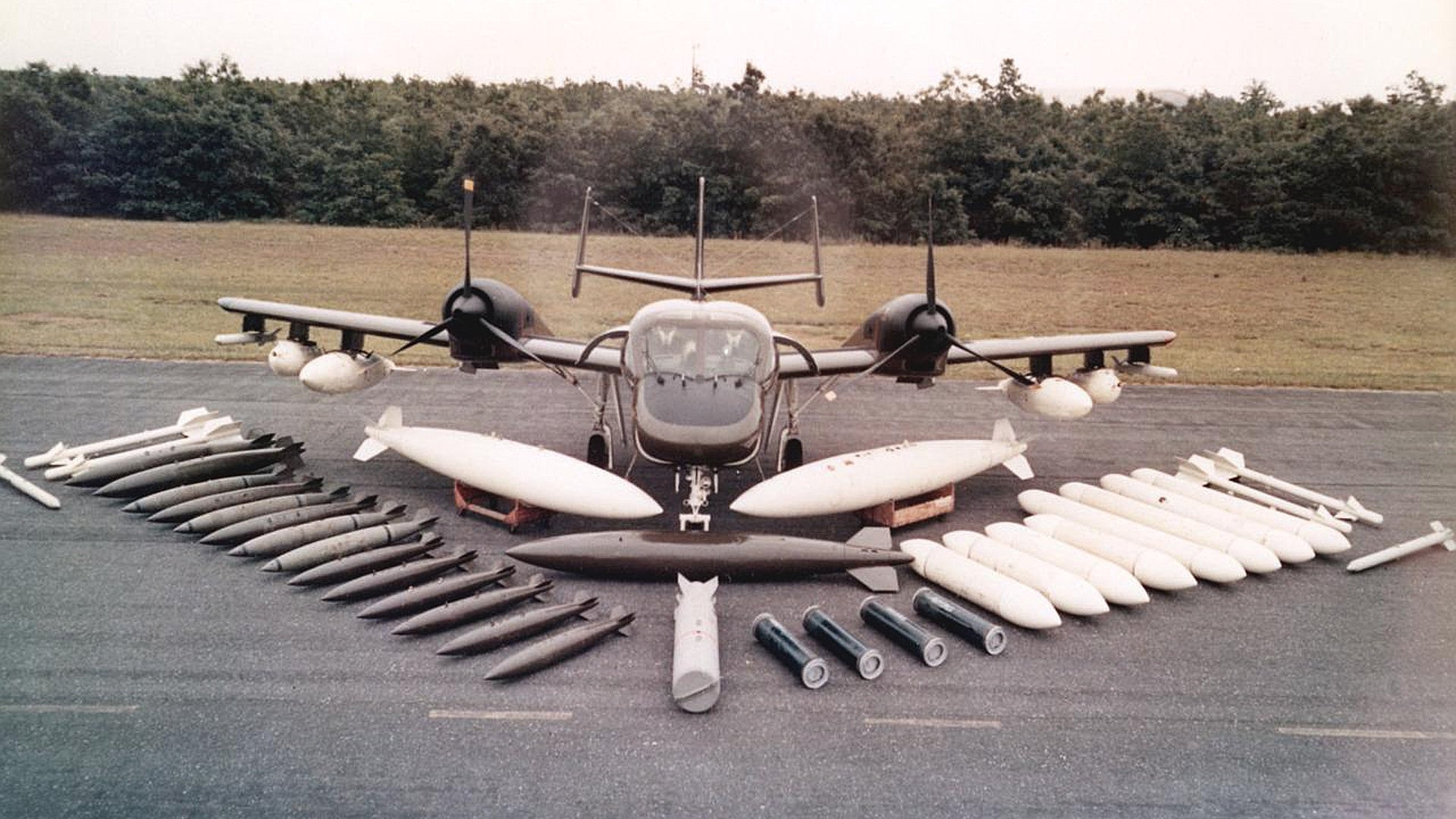

So, by the end of 1960, the Army had already begun testing the Mohawks with almost any weapons it could get its hand on. The vast majority of these were gun pods, unguided rockets, and dumb bombs.

One of the gun pods that went under the Mohawk’s wings during testing was a design containing a single .50 caliber machine gun that U.S. Air Force had purchased for T-28 Trojan propeller engine trainers that it used to train foreign air forces before delivering them directly to those countries for light attack missions – something that services still does in many ways today with its A-29 Super Tucano training program. This system contained 100 rounds of ammunition.

The Army eventually developed its own, more capable pod, the XM14, which would work with both light fixed-wing aircraft, such as the Mohawk, and helicopters. This weapon system had a faster-firing M3 .50 caliber machine gun and 750 rounds to go with it.

The OV-1s also served as one testbed for the much more obscure XM13, which contained a single 40mm M75 automatic grenade launcher. There was also the M18, with a fast-firing 7.62mm Minigun, and the XM19, containing a pair of 7.62mm M60 machine guns.

The rockets the Army tested on the Mohawk were a mix of old and new designs. These included 5” High Velocity Aircraft Rockets (HVAR) left over from the Korean War, as well as pods holding 2.75” Folding Fin Aerial Rockets (FFAR) and 5” Zuni rockets.

The possible bomb loads similarly included World War II-era types still in U.S. military inventory, as well as the more modern low-drag Mk 80-series types. The Army also evaluated the OV-1’s ability to carry napalm tanks, incendiary cluster bombs, and flare racks, the latter being useful for nighttime attacks.

But the Army didn’t stop there. What if the Mohawks had to engage larger, better-protected targets because other support was unavailable or defend themselves against enemy aircraft? In these cases, respectively, the OV-1s might have carried AGM-12 Bullpup radio command-guided missiles or AIM-9B Sidewinders.

A piece of contemporary promotional art from the Ryan Aeronautical Company depicted one of the planes carrying an experimental anti-radiation missile, presumably to take on hostile air defenses. However, this seems to have been a particularly optimistic understanding of the type’s capabilities, even against contemporary threats in the 1960s.

By 1961, Grumman itself was marketing the Mohawk as a light attack platform with a low operating cost compared to combat jets, which would be easy to fly and maintain and able to operate from areas with unimproved runways with limited support – capabilities that are still the main selling points of light attack aircraft to this day. The firm even pitched the idea of installing a 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon in a blister fairing underneath the fuselage.

While the results of the tests were generally positive and the concept of arming the OV-1As and Cs seemed particularly viable, the prospect of light attack Mohawks almost immediately ran into a number of hurdles. Opposition from the Air Force to the idea of the Army having any fixed-wing aircraft, let alone combat-capable planes, was by far the biggest.

The Army eventually renamed the aircraft it had configured to carry weapons as JOV-1A and JOV-1Cs, with the “J” standing for a temporary modification. This seems to have been an attempt to label the entire project as limited “experiment” in order to avoid complaints force the Air Force.

Even within the Army, the idea of armed Mohawks wasn’t entirely safe. Many in the service’s senior leadership were particularly opposed to giving OV-1s in any configuration to Special Forces units, which had already found themselves in conflict with “Big Army” priorities, according to the 1991 Army history.

The critics initially lost out, at least initially and in 1962, the Army began forming two Special Warfare Aviation Detachments. By the end of that year, the second one of these units, the 23rd Special Warfare Aviation Detachment, had arrived in South Vietnam with its six JOV-1Cs.

Though billed as a supporting asset for Special Forces units in the country, the planes flew surveillance and armed reconnaissance missions in support of South Vietnam Army divisions and that country’s Railway Security Agency. In the latter case, the aircraft helped guard the railroads against Viet Cong sabotage and ambushes. The aircraft’s relatively low acoustic signature made it well suited to these missions during the day and at night, flying quietly around its assigned areas and giving the insurgents less time to react and either flee the area or try and attack the plane.

Infighting with the Air Force hampered its operations with the Army eventually restricting the aircraft to load outs consisting of just a pair of XM14 gun pods and flares, which the crew could only employ in self-defense. Pictures existing that show the unit continued to employ rockets afterward, though.

The 23rd and evaluators from the Army Concept Team In Vietnam (ACTIV), which reported on the value of new technologies in the war zone, were both of the belief that these limitations prevented the Army from getting the most out of its OV-1s. “Current test restrictions prevent exploitation of the full capabilities of these versatile aircraft,” ACTIV concluded in 1963.

In 1964, the matter became increasingly moot when Army leadership finally succeeded in shutting down the 23rd. At that time, it merged with other units to form the non-Special Forces focused 73rd Aviation Company (Aerial Surveillance).

This was in many ways the beginning of the end not just for the armed OV-1s, but for the fixed wing component of the Army’s airmobility concept. In 1966, the service finally made a deal with the Air Force and ended its fixed-wing tactical transport ambitions. The next year, it passed the remaining Caribous to the Air Force, as well, leaving airmobile forces with only helicopters.

The Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps did operate a number of different fixed-wing light attack aircraft during the Vietnam War. In particular, the conflict gave the Korean War-era A-1 Skyraider another chance to shine and saw the introduction of the OV-10 Bronco, the aircraft the Marines went with after abandoning the OV-1 program.

The JOV-1s that had provisions for weapons did filter out to other Mohawk units in South Vietnam and there is significant evidence that they continued to fly with both gun pods and rockets “for self-defense” in defiance of the Army-Air Force agreement. In February 1968, U.S Army Captain Ken Lee allegedly managed to shoot down a North Vietnamese MiG-17 with a combination of rocket and machine gun fire while flying in an OV-1A over the A Shau Valley near the border with Laos, though it may simply have crashed into a mountain after trying to jump the lower and slower flying aircraft.

The story seems apocryphal given that it is hard to imagine a single MiG-17 would have been operating that far south in Laos at a time when North Vietnamese pilots typically avoided potential engagements with American aircraft, preferring to only briefly harass aircraft flying into North Vietnam and then return to the safety of their bases. And while it makes sense that Lee’s superiors would have told him to keep quiet about it the incident for fear of exposing that they were still flying with weapons, it also makes the event that much more difficult to confirm.

Regardless, it does suggest that armed Mohawks continued to prowl South Vietnam for years after they were officially supposed to cease such operations. This didn’t survive the end of the Vietnam War, though.

It’s not entirely clear what happened to the JOV-1As and JOV-1Cs, but it is likely that any surviving examples either went into retirement or got converted into OV-1Ds. This variant effectively blended the B and C models together, being able to carry the SLAR pod and infrared imaging equipment as necessary.

Some OV-1Cs and OV-1Ds also ended up as electronic intelligence gathering platforms as part of the Quick Look project. These variants became known as RV-1Cs and RV-1Ds and the Army further converted an even smaller number to an improved configuration known variously as the EV-1E or RV-1E.

Though it abandoned armed variants, the Army continued employing Mohawks for battlefield surveillance and reconnaissance missions in Europe, South Korea, and Latin America, for decades after the Vietnam War ended, notably deploying some during Operation Desert Storm in Iraq in 1991. It retired all of the remaining OV-1s in 1996 in favor the larger, multi-mission four-engine EO-5C Airborne Reconnaissance Low aircraft.

Few other countries followed suit in adopting the Mohawk, with France, Germany, and Japan all passing on the type after evaluating it. Small numbers did end up in service with Argentina’s Army and the Israel Defense Forces, as well as the U.S. Customs Service and NASA.

The OV-1 did enjoy a brief return to the limelight in the mid-2000s. After the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the security situation there quickly deteriorated, with improvised explosive devices becoming a particularly pronounced danger to U.S. and other coalition troops. The U.S. military as a whole kicked off a large number of crash programs to respond to the threat, including a host of aerial, persistent surveillance systems on manned and unmanned aircraft.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) led development on what it called the Sonoma Persistent Surveillance System. The main sensor was a large megapixel camera arrangement that could rapidly collect still images, combined with a processing system that could identify the motion of up to 8,000 vehicle-sized objects within the field of view. For perspective, the original 22-megapixel prototype camera system could take high-resolution images of an area roughly one quarter the size of Washington, D.C. The improved 66-megapixel design could scan the entire city. The third, sensor, which sources show was either a 163- or 176-megapixel, gave analysts the ability to spot targets in an area that would also have included suburbs in Maryland and Virginia.

With these images in hand, combined with the tracks noting vehicle motion, intelligence specialists could develop so-called “patterns of life” and isolate potentially unusual activity over time. In Iraq, this sort of capability helped analysts isolate activity near where American forces encountered roadside bombs and use that information to trace individuals and vehicles back to bomb-making workshops or other insurgent hideouts. Wide area surveillance systems have since become an invaluable tool for tracking small groups of militants or even individual terrorists.

LLNL eventually developed a successor system and installed it on an OV-1D that the Army pulled out of storage. This system, dubbed Mohawk Stare, which went under the nose where the SLAR pod would have been, was functional, but eventually, the LLNL and the service decided to shift platforms.

The follow-on Constant Hawk wide-area surveillance system ended up first on a contractor-operated Shorts 360 and then on ubiquitous Beechcraft King Air twin-engine turboprops. The Army subsequently bought the latter aircraft from the private companies that had been flying them and has since upgraded them, resulting in the MC-12S Enhanced Medium Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance System-G (EMARSS-G) aircraft, with the “G” standing for geo-intelligence. Another successor sensor package, Gorgon Stare, is still in service on Air Force MQ-9 Reaper drones.

The armed configuration remained largely forgotten through these twilight years. Still, one has to wonder how effective a modernized OV-1D with its own weapons to take on any targets of opportunity might have been in Iraq in the mid-to-late 2000s or Afghanistan today. It would likely have taken minimal effort to install a more modern sensor turret – the Customs Service’s Mohawks got nose-mounted forward-looking infrared turrets in the late 1970s – which could have enabled the air to conduct persistent day and night surveillance and potentially employ precision-guided munitions. This all sounds almost exactly like what the Air Force claims it wants, at least conceptually, when it comes to a prospective future light attack platform.

And when it comes to weapons, the low-cost Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) laser-guided 70mm rocket, a vastly improved derivative of the 2.75″ FFARs the Mohawks employed in Vietnam, could have been a particularly deadly option. This was the primary weapon U.S. Special Operations Command personnel employed in a limited, but highly successful field test involving a pair of modernized OV-10G+ Bronco light attack aircraft in Iraq in 2015.

If anything, the story of the armed Mohawks only underscores how much history the U.S. military has with light attack aircraft already, but that they have failed to take full advantage of for various reasons. Hopefully, the Air Force is at least making full use of this extensive institutional experience as it tries to push ahead with its latest light attack project.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com