It never ceases to amaze just how extensive the research and testing infrastructure is that supports America’s vast military-industrial machine. From radar cross-section measurement facilities that look right out of science fiction, to secret and not so secret testing airfields, to huge anechoic chambers, to a submarine test center on an Idaho lake, these facilities and many more like them, turn weapons dreams into battlefield reality.

When it comes to testing missile and missile countermeasure technology, which encompasses critical capabilities essential to national security, validating such systems’ effectiveness under many circumstances is essential. Everything from full-scale aerial targets (FSATs) to a massive soundstage-like structure that simulates missile seeker endgame performance in slow motion, exist for this purpose. And now we know of yet another elaborate testing facility related to anti-air missiles and countermeasures, one that sends helicopters careening between mountaintops along a wire as missiles attack from multiple directions.

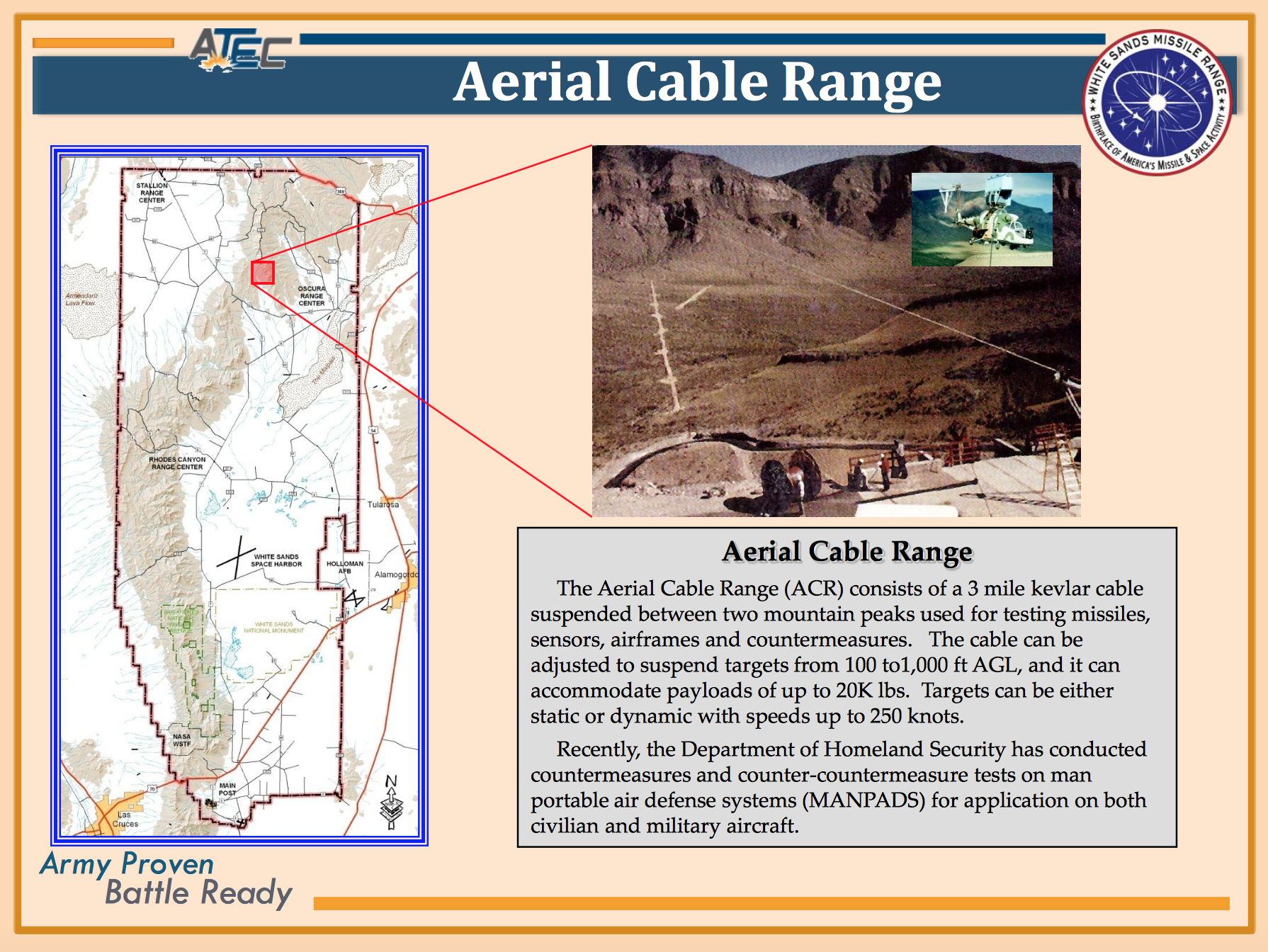

Dubbed the Aerial Cable Range, this facility is part of the sprawling White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) located in New Mexico. Managed by Lockheed Martin, the unique installation allows for simulated attacks on helicopters by anti-aircraft missile systems and other projectiles, but mainly the site is used for man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) testing and testing of countermeasure systems that aim to repulse attacks from such weapons.

The Army describes the ACR as such:

The Aerial Cable Range (ACR) is a Tri-Service facility and has conducted tests for all armed forces. NATO customers have also been accommodated to service their needs.

The facility provides a wide variety of testing which includes:

- Missile firings, Red and Blue types of Surface to Air (SAM) and Air to Air (ATA)

- Signature measurements (IR, UV, and Radar)

- Submunition Drops

- Antenna Development

- Ground fire characterization

- Aircraft characterization

- Electronic Warfare

- Countermeasure tests

The ACR target can be stationary or dynamic. Dynamic gravity rolls of targets up to 120 knots and rocket-boosted rolls up to 240 knots can be accommodated. The ACR can position targets anywhere along the cable and have the targets rotated in 5 degree increments for different aspects. Depending on the target weight and size, targets can be lifted from ground level to a maximum of 1000 feet AGL. Onboard video links, timing, GPS, remote control via Labview, modems, and wireless LANS can be accommodated.

The ACR is capable of high repeatability of test scenarios, target velocity, position, and control. Multiple launches are possible, as well as dual firings with any desired time separation.

The ACR main features are: its 2.5 inch Kevlar able with 500,000 lbs breaking strength, 15,500 ft horizontal span and 2,500 ft vertical rop, operating tensions from less than 20,000 to 150,000 lbs, and 20,000 lb lift capability.

There are no alternatives to this type of high-risk testing. The ACR provides flexible, devoted, and economic test services.

A Department of Defense article gives an even broader view of what the facility is capable of and its mission:

The range tests warning systems that alert military pilots to inbound enemy missiles. It consists of a synthetic cable three miles long, 2.5 inches thick, stretched between two mountain peaks; test platforms and targets that move along the cable; a control system to put the target in the right place at the right time, and a computer to collect and analyze data. Controllers can present moving or static targets.

“The major advantages of this system are that it provides low-cost testing, precise data and quick turnaround times between tests,” facility manager George Huffman said. The alternative, he said, is overwater testing with drones. “But drones can test only one system, one time, and that’s expensive, whereas we can conduct 200 to 300 tests a year and use the target platform over and over again, at a cost of about $11,000 per day.”

Lockheed spent $30 million to build the range, first used in 1994. Huffman said it saves DoD $80 million to $90 million a year over more expensive testing methods.

Aerial cable targets typically are no-longer-used Apache and other model helicopters the range receives for the cost of shipping from the aerospace vehicle excess storage area at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz. Weapons testers place experimental warning systems on the helicopter body, which are wired to computers in a carrier that attaches the helicopter to the aerial cable.

Once all the experiments are on board the target platform, operators activate the cable system, which works like a ski lift, slowly moving the platform up toward 8,460-foot Jin Peak. Fixed and mobile instruments prepare to capture data from the target from positions on the mountainside, in the valley and aboard the target. Testers can fire missiles from any of 10 sites a kilometer apart, stretching down the length of the mountain valley.

When everyone is ready, operators in the range control center send a signal to the cable-borne computer to launch the target and to missile launchers to fire away. Moving at speeds up to 250 knots, the cable propels the target forward until it reaches the predetermined juncture between target and missile. The missile impacts — and target debris drops to the desert floor. Within 30 minutes, crews recover the debris, keeping the fragile desert environment clean, while already the computers churn out data, and the cable is ready for the next experiments.

“Everything about this system is extremely simple,” site manager Howard Waldie said. “It allows us to easily integrate projects, and tests can be accurately and easily repeated as often as necessary.

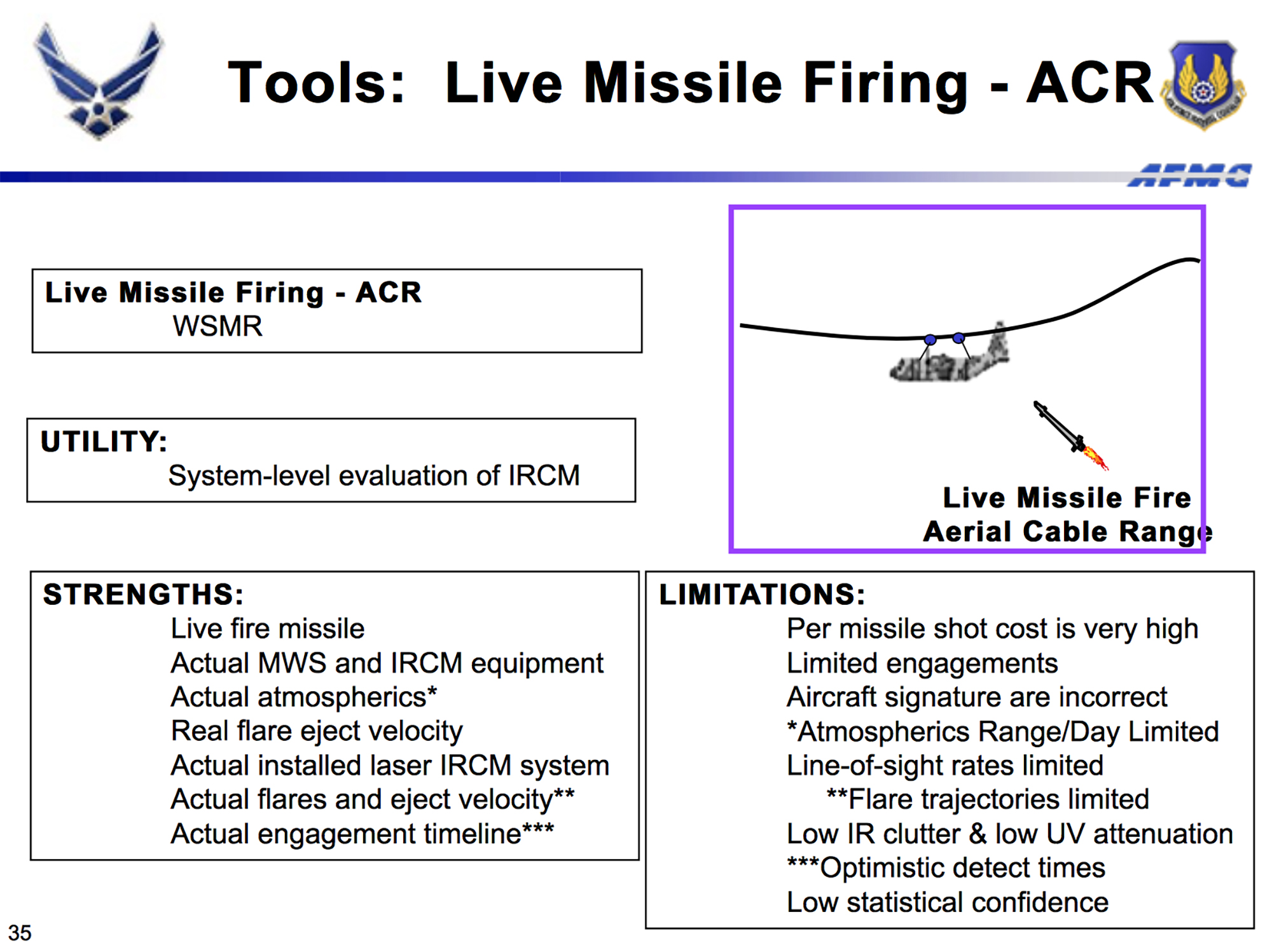

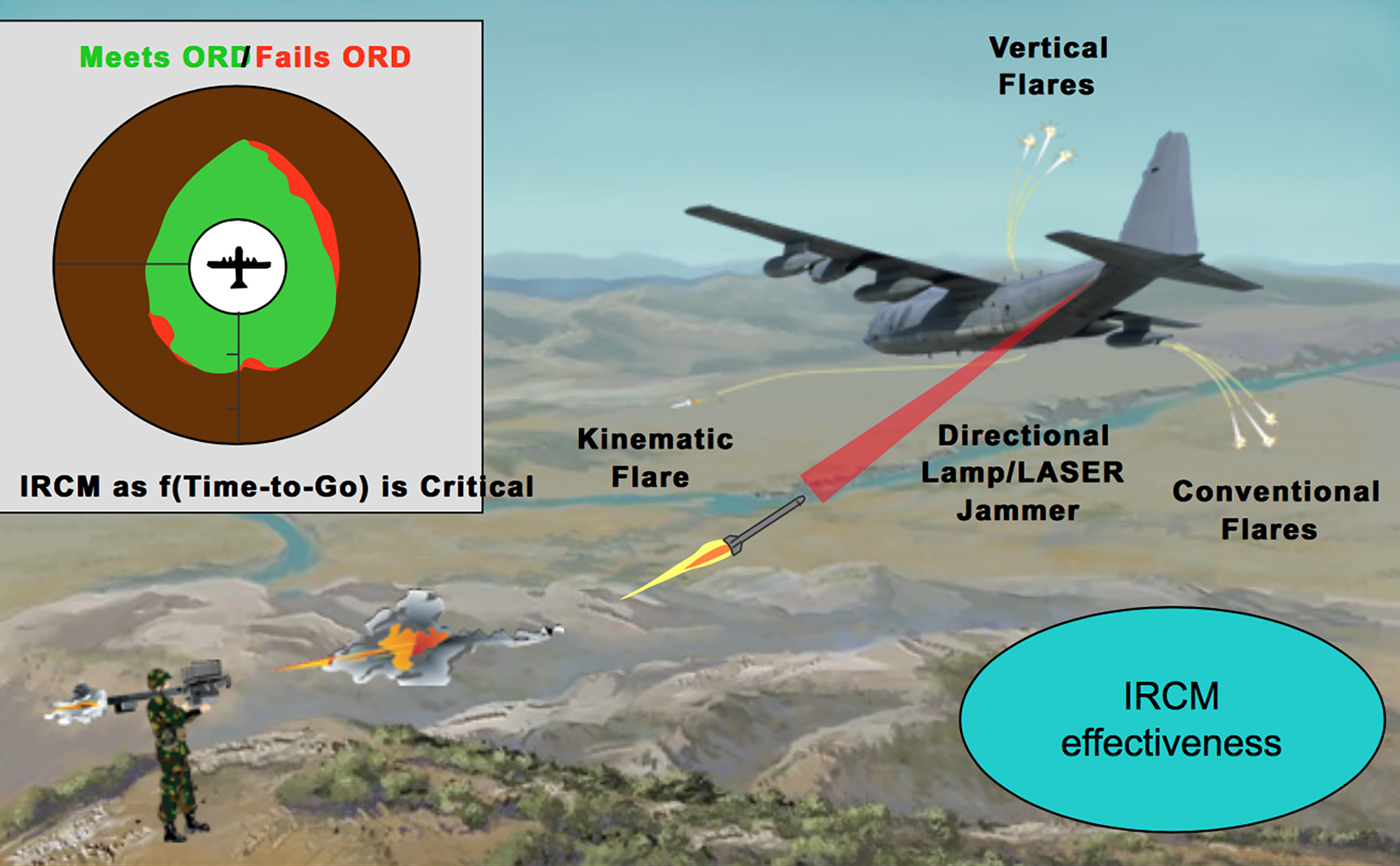

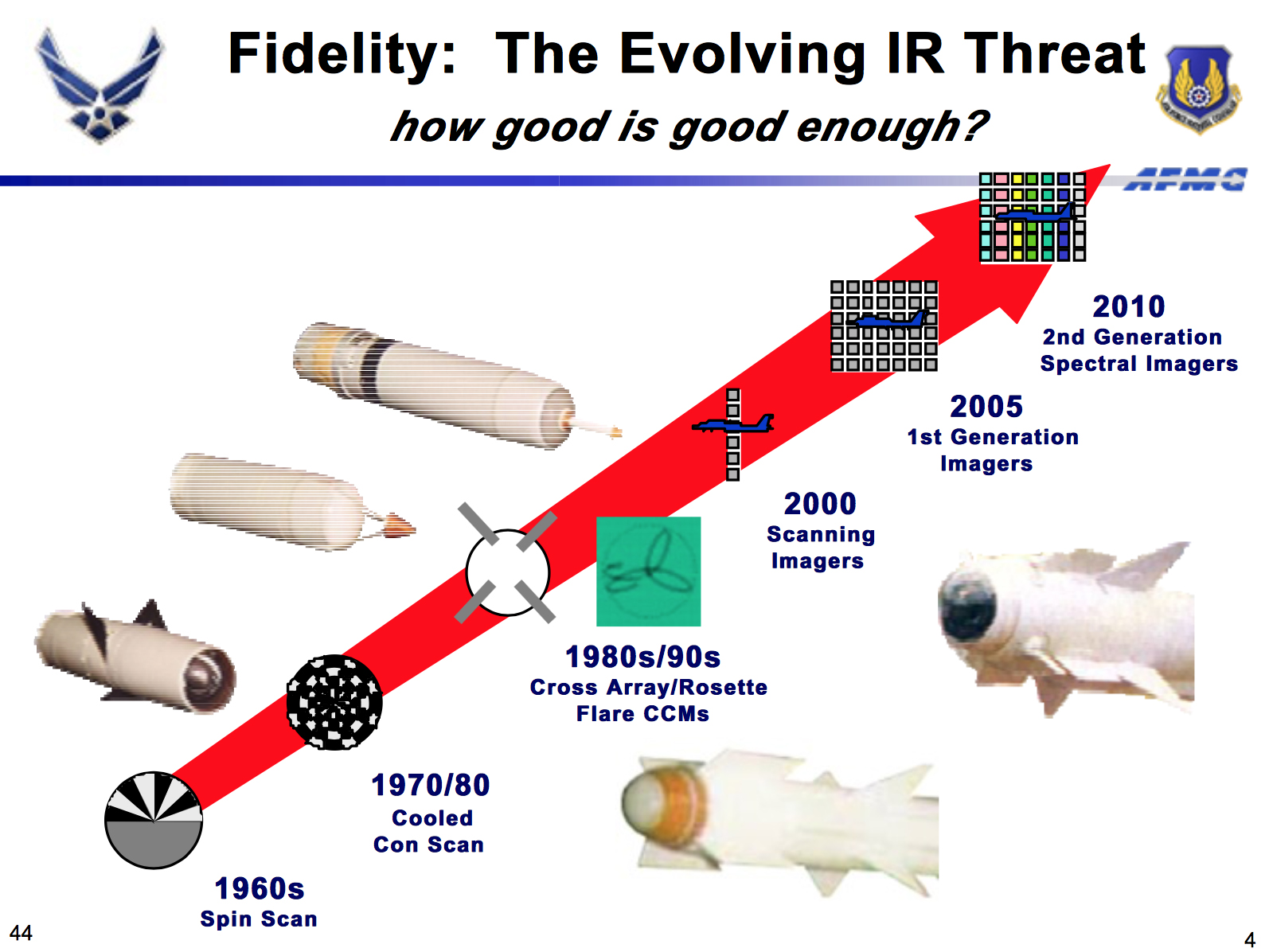

With the MANPADS threat having exploded over the last two decades, this facility is more important now than ever. Additionally, these days it is not just about countering shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles with traditional decoy flares. BOL-IR expendables and especially directed-energy (laser) countermeasure systems have provided a more dynamic counter to even the most modern MANPADS.

But all these systems have to be tested both inside and outside of a lab—you can read much more about that testing here—and the Aerial Cable Range allows the latter to happen with economic efficiency and without putting lives in danger.

A whole new set of missile countermeasures are on the horizon that could bring a ton of work to the Aerial Cable Range. These include high-power laser defenses and even short-range kinetic kill systems.

The range supports testing not just aimed at defending allied helicopters from missile attacks but also at how to better kill enemy helicopters and low-flying aircraft. The FIM-92 Stinger remains America’s MANPADS of choice and close-in point air defense is becoming a major priority for the Army and Marines due to the rise of small but deadly drones and the increased possibility of peer-state warfare without the benefit of assured air superiority.

The Stinger has been upgraded over the years and operator training is now done in elaborate domed simulators to help ensure proper application during actual combat. But America’s potential enemies are also fielding advanced countermeasure systems, such as Russia’s President-S system which is now popping up on Russian helicopters operating in Syria and on export variants. Even Russia’s newest fighter, the Su-57, is equipped with a laser countermeasure system, the first of its kind for a fighter jet.

With all this in mind, building a better missile that can’t be fooled by the latest expendable countermeasures and directed energy light beams is absolutely essential. Being able to launch these missiles during testing at surrogate airframes equipped with advanced countermeasure systems and seeing how the missiles react is critical to keeping them relevant and effective on the modern battlefield. The ACR provides this unique capability.

So there you have it, White Sands Missile Range’s Aerial Cable Range, another obscure but essential testing facility in America’s massive weapons research and development infrastructure portfolio.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com