Australia has officially announced that it is buying at least six MQ-4C Triton long-range maritime surveillance drones from Northrop Grumman, making it the first foreign customer for the type. The unmanned aircraft will significantly expand the country’s ability to monitor its extensive interests in the Pacific region and keep watch on potential opponents, such as China, as well as add to already deepening defense ties with the United States.

The Australian government and the Virginia-headquartered defense contractor both unveiled the deal, worth nearly $7 billion AUD, on June 26, 2018. In a 2016 Defense White Paper, Australian authorities had originally outlined plans to buy seven of the drones and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s government said that it could possibly pick up this additional example in the future, according to The Sydney Morning Herald.

“Australia has one of the largest sea zones in the world over which it has rights to use marine resources, also known as an Economic Exclusion Zone,” Doug Shaffer, Northrop Grumman’s Vice President of Triton Programs said in an official press release. “As a flexible platform, Triton can serve in missions as varied as maritime domain awareness, target acquisition, fisheries protection, oil field monitoring and humanitarian relief.”

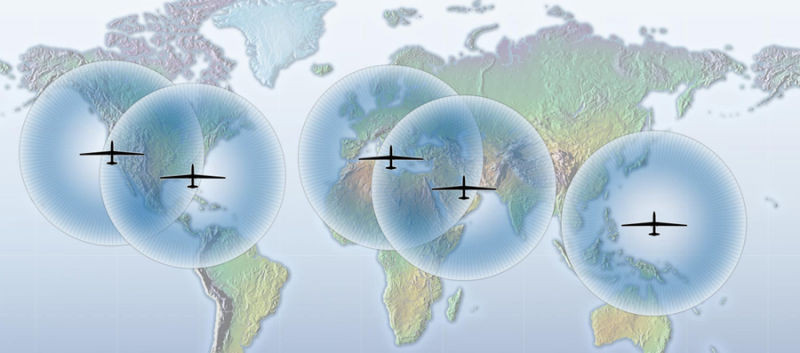

The Royal Australian Air Force plans to operate its MQ-4Cs primarily from RAAF Base Edinburgh in the south of the country, which also hosts the service’s P-8A Poseidon manned maritime surveillance planes. With a maximum, unrefueled range of more than 8,000 miles, the unmanned aircraft could fly all the way north to the South China Sea or south to Antarctica from that base.

RAAF Base Tindal in the country’s Northern Territory will also get infrastructure updates to support Triton operations. This base is less than 2,000 miles to the hotly contested South China Sea, where the Chinese military is rapidly expanding its presence on a series of man-made outposts that are increasing well defended with anti-aircraft and anti-ship weapons. Positioning the drones there could give Australian forces the ability to conduct long, persistent surveillance missions in that region.

And with the Triton’s long-range capabilities, Australia could simply use them to persistently monitor their own maritime boundaries and EEZs, as Northrop Grumman’s Shaffer noted. Australian authorities have increasingly had to find ways to stop illegal Chinese fishing in their waters and have also been in the throes of a controversial migrant crisis for years.

The MQ-4C is a derivative of the RQ-4 Global Hawk that has significant upgrades to make it better suited to persistent, over-water maritime surveillance missions. The drones have a more robust fuselage and wings, features to prevent ice build up on the wings and air intake to the engine, and improved resistance to lightning strikes, which gives them a better ability to swoop down from high altitude to more closely investigate objects of interest.

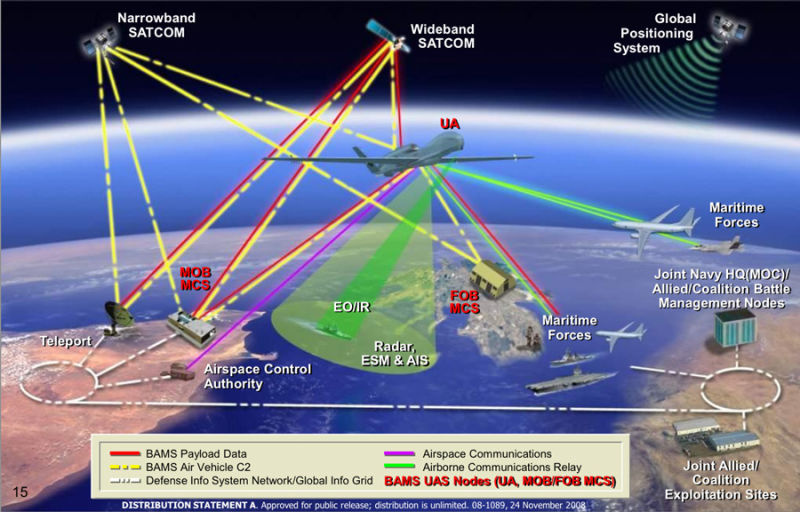

Triton’s combination of an active electronically scanned radar with surface search and synthetic aperture modes, a sensor turret containing electro-optical and infrared video cameras, and electronic support measures give it a wide array of different tools to locate and track potentially hostile ships. It also has a receiver that monitors signals the Automatic Identification System, or AIS, a marine transponder system that both navies and shipping companies use for vessel monitoring and to avoid collisions and other accidents at sea, which the drones can employ to monitor maritime traffic across a broad area.

But the MQ-4Cs could also have a very important combat support role during any crisis in Pacific Region that Australia might find itself in the midst of, such as a potential skirmish over China’s aforementioned advances in the South China Sea. Able to fly above 50,000 feet, the drones could use their multi-function radar to scan for potential threats along a shoreline or even peer deep into enemy territory while staying outside of the range at least some of their air defenses.

The electronic support measures package, the same system found on the U.S. Navy’s EP-3E Aries II spy planes, can geolocate and categorize hostile emitters, especially radars. This would allow the unmanned aircraft to help build a so-called “electronic order of battle” of an opponent’s air defense capability. American MQ-4Cs could get additional signals intelligence equipment in the future to expand their ability to monitor different types of electronic emissions and snoop on enemy communications chatter and it’s not hard to see those systems become available to the Australians in the future, as well.

The drones will also be able to share that information with other manned aircraft, especially Australia’s existing Poseidons, and ships. From the beginning, the U.S. Navy planned to pair these two aircraft together itself. The manned-unmanned team could easily cover more ground faster and the MQ-4Cs could help narrow search areas so the P-8As could better focus their attention.

“The Triton will complement the surveillance role of the P-8A Poseidon aircraft through sustained operations at long ranges as well as being able to undertake a range of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance tasks,” Australian Prime Minister Turnbull said in a statement about the drone purchase. “Together these aircraft will significantly enhance our anti-submarine warfare and maritime strike capability, as well as our search and rescue capability.”

That point about anti-submarine capabilities will only become increasingly important as time goes on as countries

throughout the Pacific, including Australia itself, look to bolster their undersea capabilities. China, in particular, is working to significantly expand the size of its submarine fleets and add both new nuclear-powered and advanced diesel-electric types to its already large inventory.

The MQ-4Cs will also be able to provide targeting information to manned aircraft and ships. This will extend the ability of those assets to strike opponents at sea and on land beyond the range of their own organic sensor suites.

In addition, the Tritons can do much of its flying and perform many of its surveillance tasks semi-autonomously, operating along pre-planned routes and identifying and categorizing potential targets by itself before passing that information to manned aircraft or analysts back at its home base for elsewhere for further exploitation. The semi-autonomous capabilities could also help the drones survive better in the event an opponent attempts to jam them or they just otherwise lose connectivity with operators on the ground.

There have already been reports that Chinese forces may be launching electronic warfare attacks on manned and unmanned U.S. military aircraft flying over the South China Sea. The drones might also be less vulnerable to blinding lasers that China’s forces have reportedly begun using in the region as well, though these non-kinetic weapons could disrupt the Triton’s cameras.

And with both MQ-4Cs and P-8As, the RAAF will be even better suited to working together with the United States during any future contingency. The two countries have already been building upon already substantial defense ties in recent years in the face of growing Chinese military and quasi-military activities across the Pacific.

“Australia’s alliance with the US is our most important defense relationship, underpinned by strong co-operation in defense industry and capability development,” Australian Prime Minister Turnbull said in his statement. “This co-operative program will strengthen our ability to develop advanced capability and conduct joint military operations.”

On June 25, 2018, Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) also quietly announced that the order was part of a Memorandum of Understanding, or MOU, outlining an active partnership in Triton operations. It also gives Australia an increased role in defining future requirements and design changes for the drones.

“Our team is eager to partner with Australia and enhance our ability to improve Australian and U.S. capabilities in that region,” U.S. Navy Captain Dan Mackin, head of NAVAIR’s PMA-262, the Persistent Maritime Unmanned Aircraft Systems office, said in a statement. “This MOU allows for enhanced partnership with our Australian counterparts and will allow us to work side by side in further developing the Triton program.”

The U.S. Navy expects to reach initial operational capability with the MQ-4C in 2021, but it plans to send the first two operational drones to Guam by the end of 2018. In June 2018, the service formally inducted the Tritons into service in a ceremony at Naval Air Station Point Mugu in California, which is home to Unmanned Patrol Squadron One Nine (VUP-19).

The U.S. Air Force already routinely deploys RQ-4 Global Hawks, the basis for the Tritons, to the island, but as noted, those unmanned aircraft are not as well suited to maritime patrols. From Guam, American Tritons will be able to monitor marine traffic in the South China Sea and in the vicinity of North Korea, among other areas of the Pacific and it is possible they could fly from RAAF bases, or even together with Australia’s drones, to further expand their ability to operate in the region.

And depending on how the arrangement goes, it might prompt other countries to renew their interest in Triton or give it a look in the first place, too. Unfortunately, the high costs associated with the drones might still be a deal breaker and have upended many potential deals already.

India, which also operates P-8I Poseidons, had considered joining the MQ-4C program back in 2011. It has since become more interested in the lower-flying maritime patrol version of General Atomics’ MQ-9 Reaper, which it refers to variously as the Type Certifiable Predator B, MQ-9B, and SkyGuardian.

In July 2018, General Atomics plans to demonstrate its drone’s overwater capabilities by flying it across the Atlantic to take part in the Royal International Air Tattoo in the United Kingdom. But General Atomics’ design still lacks the high-altitude capabilities that the much larger Triton offers.

Japan has also received U.S. government approval to buy the RQ-4 and adding MQ-4Cs to its inventory would make sense given its own extensive maritime interests. At the same time, the Japanese government has yet to finalize the Global Hawk deal and there are reports that the purchase price and high operating costs could scuttle the purchase. General Atomics also recently demonstrated Sky Guardian in the country, but as a tool for the country’s scientific research organizations.

South Korea is another potential customer for the Triton that has already been working toward buying Global Hawks and just recently decided to purchase P-8As, as well. Despite debates in the country over the RQ-4s costs, the South Korean Air Force is now slated to get the first of these drones by the end of 2018.

Whether or not any other countries decide to follow Australia’s lead, the RAAF looks set to gain an important and significant new capability. The Australian government expects to take delivery for the first MQ-4C in 2023 and have the entire fleet of six fully operational and scouring the Pacific by the end of 2025.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com