The U.S. Air Force has unveiled a number of different possible schedules for when it will award contracts under a multi-billion dollar plan to hire private companies to act as “red air” adversaries and help train U.S. military fighter pilots at a dozen different bases across the United States. The new information has emerged as one firm, Draken International, continues to secure interim contracts, setting it up to be a major competitor for the larger deal.

Air Combat Command, which oversees the bulk of the Air Force’s active duty combat-coded aircraft, released details about what it called the “Operating Location (OL) Laydown” on the U.S. government’s main contracting website, FedBizOpps, on June 5, 2018. Under the different schedules, the Air Force will award the first of multiple contracts, with unspecified values, in July 2019. It will sign the final deals as part of this adversary air, or ADAIR, program between 2020 and 2021.

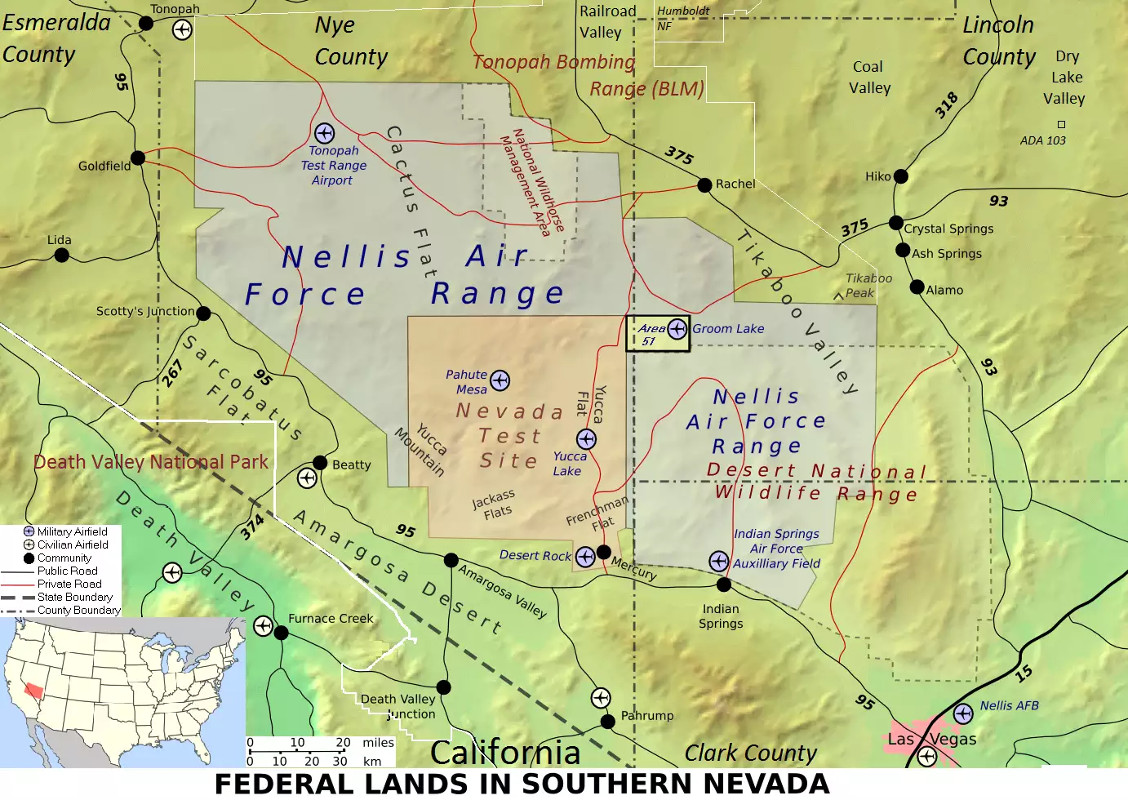

On June 1, 2018, the Pentagon also announced that the Air Force had awarded Draken a $280 million contract to continue providing training services for the 57th Adversary Tactics Group at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, as well as Luke Air Force Base in Arizona and Hill Air Force Base in Utah. Some of the firm’s L-159E Honey Badger aircraft touched down at Kingsley Field in Oregon as part of a separate deal to support the Oregon Air National Guard’s 173rd Fighter Wing on June 3, 2018. The 173rd is the USAF sole F-15C/D Eagle training unit.

The Air Force’s goal for the upcoming larger, more comprehensive contracting arrangement is to have a single overarching deal to meet its needs for contractor support during both air-to-air and air-to-ground training. In the latter cases, a private company would supply aircraft to conduct mock air strikes to help train Joint Tactical Air Controllers (JTAC) and Tactical Air Control Parties (TACP). The service reportedly expects to spend up to $7.5 billion between 2019 and 2029 on the complete ADAIR program, which could see contractors fly between 30,000 and 37,000 flight hours in total with an unspecified number of aircraft.

But it seems highly unlikely that just one contractor will have the aircraft, personnel, and overall operational capacity to meet the Air Force’s total requirements, which includes training services at 11 sites in the contiguous United States and at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. The new contracting documents further suggest that the service will award smaller “task order” contracts on a base-by-base basis within the larger “indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity” (IDIQ) deal that could go to multiple vendors.

The question then becomes who gets ADAIR support and when and how the Air Force plans to pay for the services. The service says it will decide the final timeline based on the offers it gets from companies, the results of environmental impact studies in line with National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), how much funding Congress decides to allocate for the project, and other factors as determined by its own senior leadership.

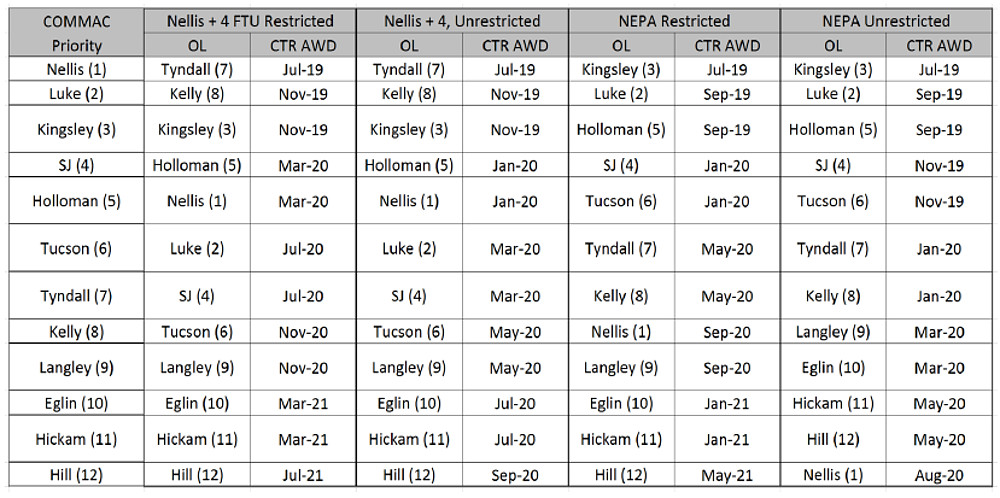

The Air Force has put together four schedules it says are “likely” and which are “based on constraints on the program known as of 1 Jun[e] 2018,” according to the recent contracting notice. “Actual fielding is subject to change at any time, including after the IDIQ is awarded.”

Two of the proposed plans involve Air Combat Command paying out of its particular budget lines, while the other two would see funding come from the Air Force’s more centralized accounts. Each pairing includes one “slow” and one “rapid” concept for handing out the ADAIR program contracts.

They all involve a total of 12 contract awards for training services at separate operating locations, but there are no prospective values for the individual deals to help indicate which ones might involve more complex requirements than others. You can see the full schedules below:

The slower potential plans exist because of concerns that the bases in question may not be able to physically handle the extra aircraft and support the increased operational and logistical strains from the extra sorties and other activity. The Air Force makes clear that the faster timelines will only work at all if it can secure the funding it needs to quickly expand the capacity at the different operating locations.

Any one of these plans would, of course, also be entirely dependent on how many aircraft a company says it has to deploy and for how long to meet the service’s demands. Beyond that, the main difference between the two sets of plans is the order in which bases would get private contractors and their aircraft.

The courses of action where Air Combat Command pays by itself are both slower overall, but would better meet the command’s priorities for ADAIR support, at least according to the contracting notice. The schedules that involve funding straight from the Air Force’s top echelons may move faster, but focus on bases the service thinks would be able to complete their NEPA reviews more quickly.

It’s not entirely clear how this could be the case based on the information provided, though. The “NEPA” plans both match up better overall with Air Combat Command’s priority listing, with the exception of the contract for Nellis Air Force Base. In one of these proposals that base, which is the number one priority, gets pushed all the way to the bottom of the schedule. Draken International already supplies adversary support to the base under a separate contract with A-4 Skyhawks and L-159 Honey Badgers being fixtures on the base’s huge apron for years now. But that capability would likely drastically increase under this expanded deal.

The idea that Nellis, which already manages a number of expansive aerial training ranges, would have more difficulty than any other site in fulfilling any additional NEPA requirements seems curious at best. Furthermore, the Air Combat Command-funded plans that are supposed to be more in line with its priorities would send ADAIR contractors first to bases it lists seventh and eighth on the priority list out of 12.

There is a fifth option to just follow Air Combat Command’s priorities in sequence. The Air Force does not offer a timeframe for how long it would take to award all the necessary contracts in that case.

Regardless of these discrepancies, under both of the two Air Combat Command-sponsored proposals, the Air Force would award the first contract, for training services at Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida, in July 2019. If the service chooses the slower version of this plan, it would sign the last deal in July 2021. The faster iteration of plan pushes that date up to September 2020. Hill Air Force Base, which has the lowest priority, would be the final recipient in either case.

The NEPA timelines also have the same start July 2019 start date, but wrap up a month earlier in both the slow and fast scenarios. However, they award contracts in the intervening period at a significantly more expedited rate. With unrestricted funding, the Air Force says it could have five deals already signed by the end of 2019 by following the NEPA-focused schedule.

Whichever schedule the Air Force decides to proceed with for the contracts, the demand for ADAIR, especially for air-to-air training, is already pronounced and only likely to continue growing. As I wrote back in December 2017:

“For more than two decades, the adversary air industry had been slowly expanding, especially in the United States. This has accelerated as the Pentagon has faced budget caps and cuts, as well as a shrinking overall force size and a worn out fleet of 4th generation fighter jets, limiting the amount of personnel and aircraft individual services can dedicate to the aggressor role itself.

“This is only likely to become more pronounced as the U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy acquire more fifth generation F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, something The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway has written about extensively over the years. It is simply not going to be cost effective to have 5th generations fighters flying as adversaries, especially for basic training duties. As for dedicated adversary units within the Pentagon’s portfolio, funds to expand the number of squadrons focused on this mission even with fourth generation aircraft is unlikely to materialize. This is especially problematic because 5th generation fighters need greater adversary capacity to train against in order to challenge their pilots.

“The Air Force in particular has scaled back their organic adversary elements in recent years. But faced with emerging threats and the need to train and challenge 5th generation fighter pilots in training, the service has become increasingly in favor of shifting increased aggressor capacity to private contractors, such as Draken. Using contractors gives the U.S. military more flexibility to schedule exercises around the training and pre-deployment needs of fleet units rather than the availability of aggressors and do so for a lower overall cost. The company provides its own pilots and maintains for its own aircraft, meaning the U.S. military doesn’t have to pull its own resources away from other priorities or maintain separate, dedicated units.”

Various contractors, such as Draken, Airborne Tactical Advantage Company (ATAC), TacAir, and Top Aces, have noticed the trend, too. As noted, Draken has already been securing hundreds of millions of dollars worth of deals to provide this kind of support at Nellis and other locations. At the former site, the company has been working with the Air Force’s highly respected Weapons School and taken part in complex, multi-national capstone Red Flag exercises.

At the same time, the industry as a whole has been looking to expand their capacity and capabilities. Most recently, there has been a push to provide aircraft that can adequately represent opponents in fourth-generation fighter jets. Both ATAC and Draken have purchased second-hand French-made Mirage F1s in various configurations specifically for this purpose.

Draken is also acquiring a number of South African Cheetah fighters, a highly modified derivative of the Mirage III. Another firm, TacAir, recently took delivery of a number of ex-Jordanian F-5E Tiger II combat jets, too.

The aforementioned commercial adversary support program at Kingsley Field in Oregon is a good poster-child for what contractors can offer. With Kingsley hosting the last F-15C/D schoolhouse in the Air Force, its throughput has suffered in no small part due to an increasing shortage of pilots across the service’s active and reserve components. Draken’s jets and their pilots will free up instructors from having to play the “red air” role and give them more opportunities to fly with new aviators instead.

“The base’s mission long-term right now is still to provide the best F-15 pilots to the combat air forces but hopefully the integration will prove that we can produce more pilots and provide higher quality training for our current 15 students,” U.S. Air Force Captain Chris Dubois, a member of the 173rd Fighter Wing, told Oregon’s Herald and News newspaper earlier in June 2018. “Leaning on their [Draken’s] experience and their depth of knowledge will help our students learn as well.”

Even more relevant is that the L-159, which packs a modern multi-mode pulse doppler radar, costs a fraction of what an F-15C costs to operate—between $25k and $45k per hour depending on how it’s calculated—in the adversary role. For new pilots, training flights are often just about learning how to execute intercepts and beyond-visual-range engagements where a very high-performance F-15 isn’t needed to act as the bad guy. As such, flying F-15s versus F-15s for new Eagle Driver pilot training, and for many regular fleet training needs as well, is hugely wasteful. It also depletes precious airframe hours on an increasingly geriatric fleet.

But while Draken’s current contracts might give them an advantage in securing a number of these future deals, the Air Force definitely looks to be setting itself up to award contracts to multiple vendors. Even spread out among a number of companies, the individual task orders for certain bases are still likely to be multi-million dollar deals and will remain a lucrative opportunity.

The contracting documents also note that the Air Force is in contact with other services, including the U.S. Marine Corps, to potentially make the ADAIR effort a joint arrangement. The Marines have expressed their own interest in contractor-operated combat jets, light attack aircraft, and even gunship helicopters for various training purposes. In addition to working with the Air Force, ATAC has already been providing adversary support to the U.S. Navy for decades, as well.

Winning one or more of the U.S. Air Force’s contract could only help boost a private ADAIR company’s profile in general. Draken, ATAC, and others are all eager to expand their business overseas.

The Air Force is clearly interested in having the contracting process as it understands it now wrapped up by the end of 2021, but we don’t know how long it might take to get the full program up and running. What is obvious is that the ADAIR industry is about to get a significant boost and it will be interesting to see how many different companies get an opportunity to take part in this new decade-long program.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com