The U.S. Army has hired a private contractor to fly an old Boeing 777 airliner from Saudi Arabia to the United States just so it can blow it apart. It may sound like a piece of the conspiracy at the center of a Hollywood spy thriller, but it’s actually part of an arrangement to help the Department of Homeland Security see how the plane might respond to a terrorist’s bomb or some other explosive incident.

On May 31, 2018, the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland announced that it had finalized the contract, worth nearly $1.5 million, with Clear Sky Aviation, LLC of Tucson, Arizona via the U.S. government’s main contracting website, FedBizOpps. Under the terms of the deal, the company will fly the Ex-Saudi Arabian Airlines

Boeing 777-268ER jet, which has tail number HZ-AKF, from that country’s capital Riyadh to Phillips Airfield at Aberdeen. The firm is also supplying four cargo sections from scrapped Boeing 747 jumbo jet airliners for additional destructive testing.

The “Aberdeen Test Center (ATC) is required to acquire and conduct commercial aircraft vulnerability testing in accordance with their interagency agreement … with [the] U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS),” an earlier contracting document explained. “ATC intends to use the aircraft solely for destructive testing purposes and agrees that it will not allow the aircraft, nor any of its component parts, to be used on any other aircraft by any party.”

HZ-AKF looks to have been a good candidate for the Army’s needs. It rolled off Boeing’s production line in 1998 and has flown almost 34,800 flight hours already. The jet has been sitting in storage in Riyadh since August 2017.

The video below shows HZ-AKF landing in Geneva, Switzerland in June 2017, just months before Saudi Arabian Airlines pulled it out of service.

In their quote, Clear Sky Aviation noted they were in the process of acquiring other 777s that might have had even higher flight hours and that it could substitute one of those for HZ-AKF if the Army was amendable. We don’t know whether or not ATC chose to accept an alternative airframe.

The original requirements called for a 777 of any subseries in a passenger configuration that ATC could pressurize to a representative level on the ground during the tests. The original request for proposals makes clear that airworthiness was not their primary concern.

For example, the aircraft only had to have “the complete landing gear assemblies or suitable replacement which could consist of time-expired landing gear components or fabricated steel components that would be able to safely support the aircraft and not hinder the aircraft from being repositioned to a specific location on a test pad as needed,” according to the initial contracting notice. “Timber shoring or cradles will not be an acceptable means of support.”

After getting HZ-AKF to Maryland, Clear Sky Aviation has a month to rip out anything it hasn’t agreed to sell to the Army and might want to keep for itself. The company says it will retain the aircraft’s two engines, the auxiliary power units, and other components.

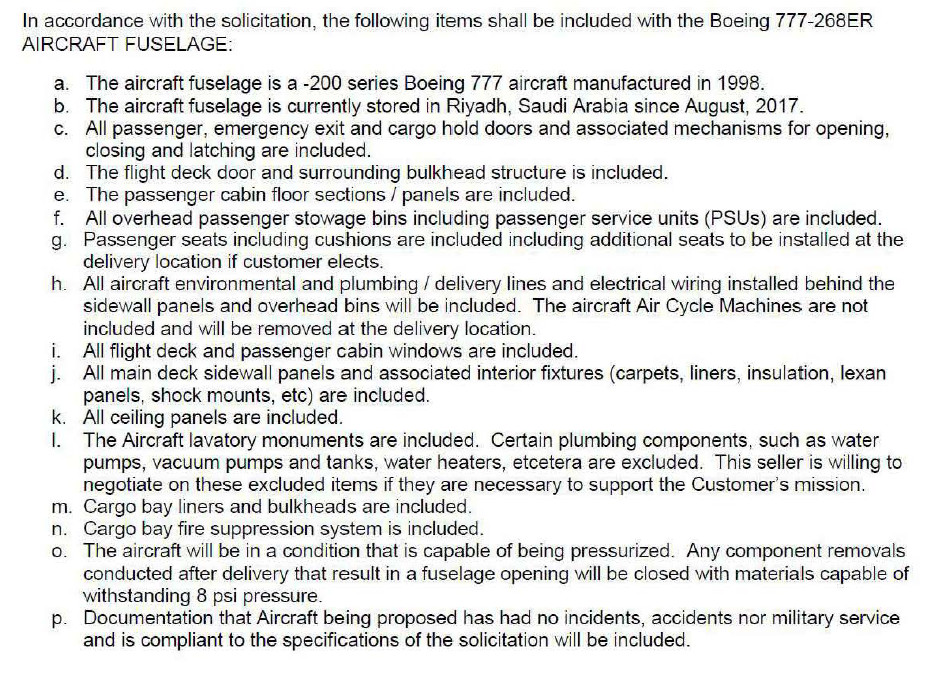

Here’s a full breakdown of what the company offered the Army:

The idea of buying an entire plane just to destroy it might seem odd, but this kind of full-scale physical testing is an important part of exploring a commercial aircraft’s vulnerabilities to terrorist attacks. We don’t know what ATC has in store for HZ-AKF specifically, but it is very likely so-called “Least Risk Bomb Location” (LRBL) testing.

These experiments are intended to determine the where the crew of an airliner can chuck a bomb if they find one and have the best chance of mitigating the explosion. Since 1972, the FAA has maintained established LRBL rules that aircraft makers can voluntarily submit to when they design an aircraft. There’s no testing requirement, though, so DHS, with the help of the Army, routinely does it themselves to examine whether the specific features hold up.

Aberdeen could easily use the aircraft for additional destructive testing, as well, and the data obtained from the LRBL experiments would likely be applicable more broadly. For nearly as long as there have been airplanes, there have been criminals and terrorists eager to hijack or sabotage them for various reasons. In 1933, in what is accepted as the first incident of its kind, a United Airlines Boeing 247 crashed after a bomb exploded on board. The case remains unsolved, but the prevailing theory it was a mob hit.

Airline hijackings and bombings surged in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the most notable attacks was the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland on Dec. 21, 1988. Then-Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi is understood to have ordered the bombing, likely in retaliation for the U.S. military’s strikes on his country in 1986 during Operation El Dorado Canyon.

As such, full, destructive testing has only become increasingly valuable as a means to let investigators, engineers, and scientists see firsthand what sort of damage results from different types of explosives going off in different portions of the plane. At the same time, the data can be useful for training individuals to spot certain telltale signs that point to a bombing rather than some sort of accidental malfunction.

In many ways, the explosive destructive testing is also similar to other fatigue and environmental torture testing, which also look to stress an airframe to discover potential vulnerabilities before they become a more serious problem. Some of that same data from Aberdeen might help uncover potential weaknesses in various aircraft types to other kinds of possibly catastrophic failures.

There’s a continual need to test more aircraft as new threats emerge, as well. A plot in 2006 to use liquid explosives to bring down airplanes fundamentally changed airport security procedures. In 2015, ISIS terrorists claimed they had brought down a Russian airliner over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula using a bomb hidden inside a soda can. Pre-existing data might not have been applicable in determining the exact danger that either these types of devices posed to commercial flights.

More recently, Boeing’s 787 suffered a number of problems with its lithium-ion batteries, which led to a number of serious fires and exposed the potential danger from any device using one. Civil aviation authorities have since continued to explore the impacts of these power sources experiencing a “thermal runaway” and either bursting into flames or exploding. In 2017, the FAA went as far as to propose a ban on laptops in checked baggage as result.

There’s also just normal wear and tear and other hazards. The engine on a Southwest Airlines 737 exploded in mid-air in April 2018, which led to the death of one of the passengers. Bird strikes can also have serious consequences, especially if they impact a jet’s engines.

So, for decades, various U.S. government agencies have carried out representative explosive testing on retired airliners for forensic and other purposes. In 1984, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) joined forces to deliberately crash a remotely-piloted Boeing 720 at Edwards Air Force Base to study the result of the impact on the airframe and simulated occupants.

Authorities in other countries have done the same. In 2015, the United Kingdom’s Civil Aviation Authority and the FAA worked together to blow up a retired Air France Boeing 747-100 jumbo jet at Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome north of London.

Three years earlier, the Discovery Channel paid to smash a remote-controlled Boeing 727 into the desert near Mexicali, Mexico. Similar to the FAA-NASA test in 1984, researchers filmed the impact from the exterior and interior and turned the event into a television special.

Private companies have also used destructive testing to explore potential ways to mitigate or defeat terrorist bombs on airliners. In 2015, a European consortium led by a U.K.-based company called Blastech blew apart cargo holds from an Airbus 321 and a Boeing 747 to test prototypes of a system called Fly-Bag, intended to contain the explosion within the compartment to keep a plane aloft and the crew and passengers safe.

We don’t know exactly how long ATC’s own effort has been going on, but in 2012 the Army put out a similar contract to buy a single Embraer ERJ-145 regional jetliner for destructive testing. The next year, pictures showed portions of an Airbus A300 and Boeing 737, 757, and 767 aircraft sitting at Phillips, according to a story from Aviation Week. In August 2013, the Army put the ex-China Airlines A300 hulk up for sale to make room for another jet.

Clear Sky Aviation, which has a nearly non-existent web presence, was also able to sweeten its proposal by noting that it has delivered aircraft to the Army for these purposes in the past. The company said it had flown at least one Airbus A300, as well as a Boeing 757 and 767 types – the ones seen in the 2013 images, to Aberdeen for previous experiments.

According to the final contract, HZ-AKF is supposed to touch down at Aberdeen in November 2018, but we don’t know when the actual tests might occur. But if anyone spots the jet flying in, they might be seeing it for the very last time!

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com