The U.S. Air Force has detailed its plans for buy as many as 112 sets of new wings for the service’s remaining, so-called “thin wing” A-10 Warthog ground attack aircraft. Unfortunately, there’s no guarantee the service will purchase that many replacement spans and, under the present schedule, the first of these vital kits won’t be ready for years, which could push dozens of the planes into retirement.

Correction: See details at the bottom of this story.

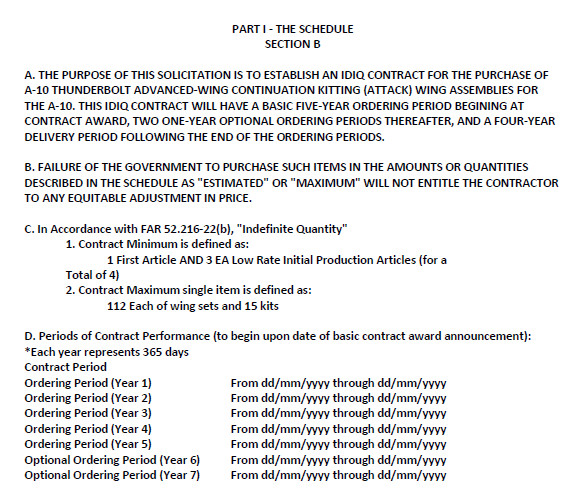

On May 25, 2018, the Air Force released the official request for proposals for what it is now calling the A-10 Thunderbolt Advanced-Wing Continuation Kit, or ATTACK program. This refers to the aircraft’s official name, Thunderbolt II. As it stands now, the service is expecting a year-long contracting period followed by at least five years of orders. There are two possible optional ordering periods, as well.

The “indefinite quantity” contract would be for a minimum of four sets of wings. If the Air Force decided to pursue all of its options, the maximum order would be for 112 spans, plus 15 spare kits.

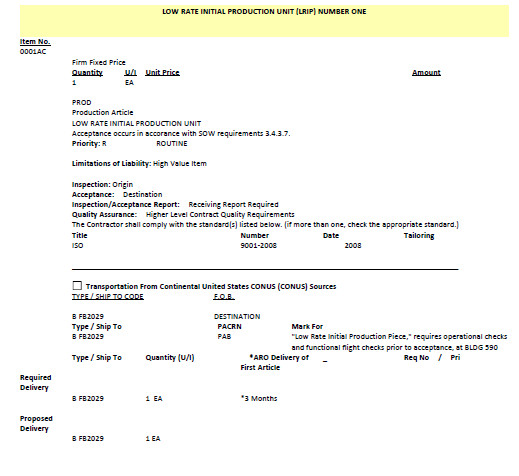

But most shockingly, the notice specifically says that actual deliveries would only start four years after the last of the first five ordering periods. The contractor responsible for the program would only have to deliver the first four low rate initial production kits by 2029. [Correction: This is incorrect. The earliest date at which the wing kits would arrive is some time in 2022]

After that, the Air Force would then decide whether or not to pursue full-rate production at a maximum of four wing sets per month. The service says the minimum threshold is for a contractor to deliver three kits every month. At these rates, it would take between two and three years to produce 112 new wings.

Of course, the issue is that the more than 100 “thin wing” Warthogs, approximately a third of the total fleet of more than 280 aircraft, need the new spans now. Re-winging the planes has already become a saga since the Air Force ended the first such upgrade program early, which left dozens of the ground attackers without the new “thick wings” that would keep them safe to fly into the 2040s.

The Air Force has already had to resort to an unspecified “collaborative approach” to prevent wing-related groundings in the 2018 fiscal year, which ends on Sept. 30, 2018. As of May 2018, the service had not retired an A-10 in any configuration to the Bone Yard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona since 2015, according to an official inventory it releases every month.

There will almost certainly be groundings, though. In April 2018, U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Jerry Harris, the service’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans, Programs, and Requirements, told legislators that he was only confident that his service could prevent any groundings occurring after 2025.

With the first new wings are only set to start arriving four years after that, though, it raises the question of how this could be the case. There is a distinct possibility that Harris is so confident in that timeline because, by then, all of the thin-wing A-10s will be stuck on the tarmac or in the Bone Yard.

This would be largely in line with the Air Force’s plan to increase the size of the six active duty and Air Force reserve component A-10 squadrons while shutting down the three remaining units. The implication here is that at least 80 Warthogs would be headed for permanent retirement.

If this were to happen, the Air Force, which has long been opposed to the A-10s at an institutional level, would have no desire or need to re-wing all of the thin-wing aircraft. In January 2018, it emerged that Todd Mathes, the A-10 Program Element Manager for Air Combat Command, the Air Force’s top warfighting command, had reportedly made it clear to his subordinates that full program was “not going to happen.”

And even if it did, there is no guarantee there would be funding available for all 112 wing kits. As of 2018, Congress has approved more than $100 million in the 2018 fiscal year for the re-wing effort, but this only pays for four pairs of wings – the minimum low-rate production the Air Force has identified – along with rebooting the production line to make more. The Air Force’s latest budget request for the 2019 fiscal year includes a little more than $79 million for an unspecified number of wings.

However, according to official questions and answers the Air Force released along with the request for proposals, one prospective contractor noted that this would not cover the maximum purchase order. The service, referring to itself as “the Government,” insisted that its goal was to buy all 112 spans, but noted that there was no guarantee.

“Additional funding is unknown past [fiscal year 2018] based on Government budgeting cycle,” the response explained. “If additional funding becomes available, the Government would consider a more aggressive schedule and higher quantity orders.”

It’s a tall order for any company to tool up to produce these replacement wings at all, especially since the Air Force is the only service in the world to operate the A-10. Those same firms are likely to face a hard decision about whether to compete knowing that the service can’t guarantee purchases beyond the first four kits.

It could also impact the contractor’s actual preparations to meet the production goal of at least four pairs of wings every month. Any delays in awarding the contract or moving from low-rate to full-rate production will only exacerbate the need to ground A-10s without the replacement wings as they hit their maximum safe allowable flight hours.

I have noted in the past how all of these intertwined timelines could have broad effects, writing:

This could have a cascading impact on pilot and ground crew proficiency with the Warthogs. In turn, the Air Force might feel it has a stronger case for retiring those particular planes for good and either converting the three squadrons to fly other aircraft or distributing the personnel to other units. If that were to happen, any impetus for completing the re-wing effort would evaporate entirely and Mathes would be right to say that it’s “not going to happen.”

Congress, however, is unlikely to agree with this course of action. Legislators have repeatedly blocked the Air Force’s attempts to retire the A-10 absent an adequate replacement and have so far dismissed the service’s assertion that the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter can take over the Warthog’s missions, instead ordering a fly-off between the two aircraft that could begin later in 2018.

At a certain point, opposition from lawmakers might not matter, though. Congress can block the Air Force from retiring any A-10s forever, but it won’t be able to make jets without the new wings any more airworthy with just the stroke of a pen.

Legislators who support keeping the Warthogs on active duty for the foreseeable future appear to face a no-win situation of either agreeing to trimming the fleet or compelling the Air Force to maintain units with aircraft that are increasingly unflyable as the service suffers a growing shortage of pilots. There is significant evidence suggesting that this has been the service’s plan all along in delaying A-10 upgrades in general.

Even if the Air Force can stick to its stated re-winging timeline, this scenario only seems increasingly inevitable. It is plainly unreasonable to believe that the Air Force’s priorities will remain the same in the decade between ordering the first wing sets and taking delivery of them. [Correction: this time frame will only be approximately four years long] Most notably, the service is still planning to evaluate the performance of the A-10 against that the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter in the close air support role.

It is unlikely that the battle for the A-10 is over entirely and the aircraft’s supporters in Congress are sure to push for the Air Force to maintain at least some of the aircraft for the foreseeable future as they have repeatedly in the past. And in the last 18 months, the service’s senior leadership has made a number of very public overtures of support for the Warthog, but they have all come along with major caveats.

“In the [2019] program that we’re working, we also buy more wings, and so we move forward to address the wings of the A-10,” U.S. Air Force General Mike Holmes, head of Air Combat Command, said at a talk at the Brookings Institution in January 2018. “As far as exactly how many of the 280 or so A-10s that we have that we’ll maintain forever, I’m not sure.”

Having a fleet of 200 A-10s or fewer could give new weight to the service’s long-standing desire to divest the entire fleet, as well. The service has a number of similarly shrinking fleets of various combat aircraft, such as the F-15C Eagle and F-22 Raptor stealth fighter.

In turn, these aircraft have become steadily more complicated and expensive to fly and maintain with increasingly limited abilities to contribute to a large end-strength for actual combat operations. The future of the so-called “Golden Eagles” remains particularly uncertain.

In offering new details about it how plans to “save” the thin-wing Warthogs, the Air Force seems to be making it increasingly clear that close a third of the total fleet is barreling towards full retirement in the next few years.

Correction: The original version of this story inaccurately stated that the first wing kits would only arrive in 2029, approximately a decade after the likely date of the contract award. This was based on a misreading of the contracting documents, which mention “B FB2029” in the specific line items.

Though this looks like a date code, it is actually a facility at Hill Air Force Base in Utah where the re-wing project will do its work. In addition, the still curious plan to proceed through four full calendar years of orders before taking delivery of any actual components further confused the timeline.

The accurate time frame is as follows. The Air Force will a complete year-long contracting period followed by four, year-long ordering periods, for a total of five years. Only after that does the service expect to begin taking delivery of any new wings. We do not know when the contracting period started or when it will end.

If the contracting period ends in 2018, then the first wings should arrive in 2022. If the contract award only occurs in 2019, this date would be pushed back to 2023. The full ordering period is supposed to run for four full years, meaning the last kits would arrive in 2026 or 2027. There will also likely be some lag between when the Air Force gets the wing sets and when the upgraded A-10s return to active duty.

But it is also unclear how the two additional 365 day-long optional ordering periods fit into this timetable. If they delay the start of the delivery periods, then the full program could run through 2028 or 2029 in the end. In addition, the 2022-2023 delivery date would only be for the first four low-rate production kits, with full-rate production at between three to four kits per month coming some time afterward.

It also remains unclear how the various figures line up. A contractor fulfilling a maximum order of 112 wing kits and 15 spares at four kits per month would meet that obligation in less than three years. The only way this could take between five and seven years is if the Air Force does not actually keep to that production schedule.

Regardless, The same issues noted above continue to be relevant even with this corrected timeline. Groundings are almost certain to occur before the first wing sets arrive and could have the same cascading impact on the thin-wing A-10 fleet.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com