Recently, the U.S. Marine Corps announced its interest in hiring contractors to fly a Russian-made Mi-24 Hind gunship as a mock enemy during training exercises. It wasn’t always this easy to get access to one of the helicopters. Near the end of the Cold War, in an operation that seems made for a major Hollywood movie, a U.S. Air Force C-5 Galaxy transport plane discreetly flew U.S. Army special operators and a pair of MH-47D Chinooks from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment to the African country of Chad in order to steal one of the big attack choppers.

On May 21, 1988, the U.S. military had ordered the start of the mission, known as Operation Mount Hope III, with the relatively simple objective of having the elite Army aviators get to northern Chad and extract a Mi-25 Hind D – the export designation for Mi-24. Libyan forces had abandoned the aircraft, and a host of other equipment, as they retreated after suffering a major defeat at the hands of the Chadian military under the leadership of then-President Hissen Habré.

The preparations for and execution of the operation were anything but easy, though. It was “one of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment’s earliest successes and the first major operation utilizing the mighty Chinooks,” an officer from the unit subsequently wrote in a brief history of the mission, which The Black Vault, a repository for previously classified government documents, subsequently posted online.

The circumstances that led the Hind to be sitting abandoned at the Ouadi Doum Air Base in northern Chad go back decades earlier. After seizing control of Libya in 1969, strongman Muammar Gaddafi sought to spread his influence and revolutionary ideology across north and central Africa. In addition, he was eager to take control of a contested border region known as the Aouzou Strip, which had become part of Chadian territory after that country gained its independence from France in 1960.

For nearly a decade starting in 1978, Gaddafi launched interventions into his southern neighbor and otherwise sought to meddle in the country’s affairs, supporting various rebel groups over the years. In December 1986, the last of these groups, an umbrella organization known as the Transitional Government of National Unity, or GUNT, upset with the Libyan dictator attempts to undermine its leadership and failure to provide economic support in regions under its control, turned on him.

Habré seized the opportunity to launch an offensive to regain control of the northern portion of his country. His forces predominantly employed pickups and other light wheeled vehicles and the ensuing conflict became known as the Toyota War. With support from the United States, France, and what was then known as Zaire – now called the Democratic Republic of Congo – the Chadians routed the Libyans and had driven them from the country entirely by the end of 1987.

The U.S. Intelligence Community, particularly the Central Intelligence Agency, was already heavily invested in the country and became aware of the Mi-25 in Ouadi Doum. The U.S. government was eager to get its hands on one of the Soviet’s then most advanced helicopter designs.

The process of acquiring foreign military equipment to analyze its capabilities and weaknesses, known as Foreign Materiel Exploitation, or FME, remains an important mission for the U.S. military and the U.S. Intelligence Community. At the time, getting a Hind was especially important since the gunships were already participating in a number of conflicts where the United States had active interests, including the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq War, and Nicaraguan Civil War.

Below is an old Cold War-era US Army training video covering the Hind and other Soviet helicopters.

Though Habré was not necessarily opposed to the United States taking the Hind out of Ouadi Doum, he had no interest in being seen delivering the aircraft to the Americans himself. It took months of negotiation to get Chadian authorities to finally agree to the Mount Hope III plan, which was likely more complex than it had to be due to the political considerations. According to another story of the operation from War Is Boring, the United States sweetened the deal with a $2 million payment and a shipment of FIM-92 Stinger shoulder-fired, man-portable, surface-to-air missiles.

Even as the debate with the government of Chad continued, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment was conducting exercises just to see if the basic idea was feasible. In March 1988, the unit performed a largely written study, possibly known as Operation Mount Hope, which concluded the MH-47D would be able to lift the Hind and still carry the required fuel load, according to a now declassified historical briefing The Black Vault also obtained.

The next month, the special operations aviators performed a complete dry run, known as Mount Hope II. They first loaded two Chinooks onto a C-5 at Fort Campbell in Kentucky and flew to a simulated forward operating site at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

The crews from the 160th then took a route spanning 490 miles to a mock target site where one of the two Chinooks lifted six collapsible bladders, or blivets, filled with water simulating the weight of the Soviet helicopter. They then returned to the staging base, stopping twice to refuel at temporary Forward Arming and Refueling Points, or FARPs. The early model MH-47Ds the 160th employed on the mission did not have an in-flight refueling capability.

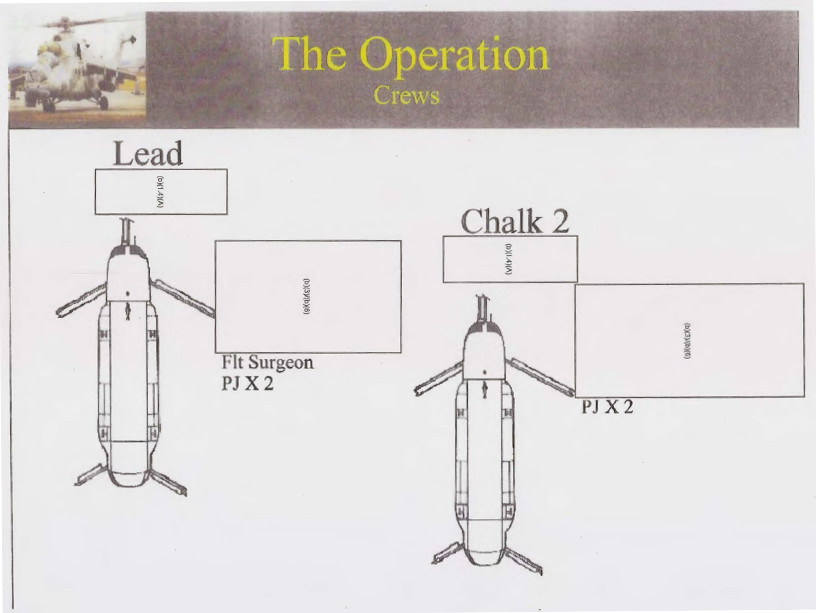

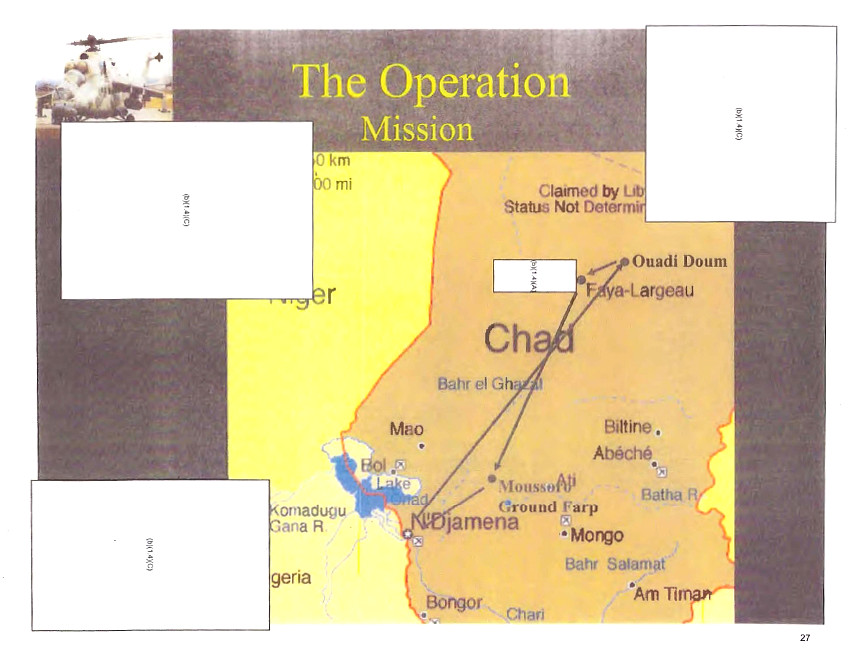

After receiving the formal order to begin the mission in May 1988, an advance party went first to Germany and then on to the Chadian capital N’Djamena to prepare for the arrival of the main force. On June 10, 1988, Mount Hope III began when a C-5 with two MH-47Ds from Company E, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, as well as approximately 75 additional personnel, flew from Fort Campbell to N’Djamena.

Censors redacted the names of these individuals and what units they were assigned to in the briefing The Black Vault posted online. Given the secret nature of the operation, it is possible the additional manpower came from other secretive special operations forces units such as the Army’s Delta Force. U.S. Air Force pararescuemen and a flight surgeon were also part of the task force that actually traveled out to Ouadi Doum.

The next day, June 11, the Americans flew nearly 500 miles straight from N’Djamena to the air base, with an escort of French forces, including Mirage F.1 fighter jets. The situation there was tense with reports of increased Libyan activity on the other side of the Aouzou Strip. Months before Gaddafi’s forces had sent his own aircraft to try and destroy abandoned planes, helicopters, and other equipment in the area.

When they arrived, the Mi-25 was more or less ready to go. Other American and French personnel had been at the site and elsewhere in northern Chad for months, salvaging other aircraft and equipment. They had tucked the Hind away at the base until the U.S. military could figure out how best to get it out of the base.

With the gunship slung below one of the MH-47Ds, the American force then left for the return flight to the Chadian capital. The helicopters stopped at Faya Largeau and Mousorro to refuel at FARPs that a crew of a U.S. Air Force C-130 transport plane had established for the mission.

The U.S. personnel conducted the entire mission under some extreme weather conditions. The peak heat the task force encountered that day was reportedly 130 degrees Fahrenheit.

More worryingly, as the helicopters got close to their final destination, the crews found themselves in the middle of a massive sandstorm. Trying to keep a tight schedule, the two MH-47Ds reportedly flew at speeds less than 50 miles per hour and within visual sight of each other until they emerged on the other side.

The sand followed them to N’Djamena, though, and they had to sit in the safety of their Chinooks for more than 20 minutes until the weather cleared and they could begin loading everything back onto two C-5s. In total, the American force spent less than 70 hours in Chad before returning to the United States with their prize.

For the 160th, which the Army had first begun to form in 1981, it was a major achievement that involved complex mission planning and long-distance staging and operational movements. It also proved that the unit could perform heavy-lift operations under unusual and demanding conditions.

It is almost certain that the organization put some of the lessons learned into action in 1989 during Operation Just Cause in Panama, which involved the long-range self-deployment of MH-47s, including over-water flight, into the country using FARPs. In 1991, the 160th was called upon to demonstrate its capabilities in a desert environment again during Operation Desert Storm in Kuwait and Iraq.

The 160th has since become the U.S. military’s premier special operations helicopter unit, taking part in a host of different missions around the world in more than three decades since Mount Hope III – and likely more that we may never hear about. Separately, CH-47 and MH-47 Chinooks from across the U.S. Army have increasingly become a go-to platform for air assault operations, especially for still-ongoing operations in Afghanistan.

Unfortunately, we don’t know if any of 160th’s MH-47s have grabbed any more foreign aircraft covertly. Chinooks have certainly shown off their ability to carry helicopters and aircraft since the mission in Chad.

The central African country, and U.S. military involvement in Africa more broadly, is back in the news, too, but without many of the players from 1988. In 2016, a special African Union court in Senegal convicted Hissen Habre – who had been living there in self-imposed exile since insurgents unseated him in 1990 – of gross human rights violations and other crimes, including mass rape and ordering the murder of more than 40,000 people during his tenure as leader of Chad, and sentenced him to life imprison. Libyan rebels executed Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 after his regime collapsed in the face of a U.S.-led intervention. That country remains mired in violence the better part of a decade later.

If the U.S. military needs to go out and snatch a helicopter again, the 160th is probably still up for the job. But if it needs more Hinds, it’d be much easier to just call up private firms in the United States now to get them.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com